Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – April 3, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Greece would have to undergo a period of austerity even if the Greek government left the EMU, restored its currency and renegotiated all Euro debts into the drachma (that is, defaulted). This is because investors would be reluctant to purchase Greek government debt and they would have to reduce their net spending accordingly.

The answer is False.

Once the Greek government reinstated its currency sovereignty and allowed the drachma to float freely then it could choose whatever net spending position it desired irrespective of the desires or otherwise of the private investors for its debt and the assessments of the ratings agencies.

To get to that point it would have to renegotiate all Euro-denominated public liabilities but Argentina showed in 2001-02, the defaulting nation in this case holds all the cards.

For its own citizens it could also exchange drachmas for euros (at some fair rate) prior to the depreciation that would follow for those who wanted their wealth to be preserved in the local currency. Please read my blog – Exiting the Euro? – for more discussion on this point.

The Greeks would have to then take measures – such as reforming their tax base to ensure stable growth was achievable. That is, with the significant leakage into the cash economy, the effectiveness of fiscal policy in attenuating demand growth is reduced. So whether they stay in the Eurozone or leave, tax reform is required as a matter of urgency.

As noted in the blog, the tax reform, would have nothing to do with increasing the capacity of the Greek government to “raising funds” to allow it to spend. Once they exited the EMU the Greek government would be sovereign again and face no revenue-constraints on its spending. Rather, the tax reforms would give it more flexibility to control aggregate demand and align it better with real output capacity.

It is likely that bond markets would retaliate and boycott Greek government debt issuance. The Government would then have two options – both of which would be completely within its power.

First, it would have to reform the central bank arrangements to ensure that the elected government restored influence on monetary policy. One of the pre-conditions placed on nations desiring to enter the EMU was that requirement that the central bank was made completely independent. Independence on steroids was how one commentator at the time described the arrangements.

So with new legislation, the elected government could instruct the central bank of Greece to manage the yield curve should the bond markets boycott the issues.

Second, more sensibly, the Greek government could ignore the rating agencies altogether and dispense with the unnecessary practice of issuing any debt. This would give it some more scope for improving employment and welfare within the inflation constraint.

An exit and resulting flexible exchange rate would also allow the nation to realign its traded-goods sector with those of its trading partners without having to scorch the domestic economy and impoverish its workforce.

One would predict that a fairly substantial depreciation of the newly-introduced drachma would occur. But Australia has seen swings from 48 cents US to rates in the 90+ cents US in periods of 3-5 years without any fundamentally negative results. Certainly not runaway inflation.

The depreciation would reduce the capacity of Greeks to purchase foreign goods and would add some price pressure (albeit finite and small) to the Greek economy. But the inflationary impact is not likely to be substantial if managed correctly.

This should ease the worries that some people have who think that the depreciation would be inflationary. As I explained in this blog – When you’ve got friends like this … Part 3 – there is “no mechanical link between the exchange rate and the inflation rate” (Source: Bank of England’s inflation outlook).

Further, the Bank of England’s inflation outlook tells us that:

The exchange rate is a key factor affecting inflation prospects, although it is very difficult to predict. There is, however, no mechanical link between a change in exchange rates and inflation.

A change in the value of sterling can have a direct influence on inflation through changes in import prices … But this is primarily a one-off impact on prices and so a temporary influence on the inflation rate.

It is clear that the depreciation would drive a once-off adjustment to the terms of trade and so imported goods (like military equipment) would become more expensive. This doesn’t necessarily result in inflation if the consequences are sequestered from the distributional system and the nation takes the “real” cut in living standards that is implied.

This real cut can be attenuated by increased government provision of non-traded goods. Further, the domestic non-traded goods sector suffers no negative impacts and goods and services emanating from that sector form the bulk of private consumption anyway.

Further, the real cut via the depreciation is likely to be of a much smaller magnitude than the austerity plan they have in place at present.

Finally, the improving terms of trade will make the Greek export products including its tourist and shipping industries more attractive and net exports would likely be boosted adding to domestic growth.

So upon exit, the Greek government would become responsible for maintaining aggregate demand and could increase employment and income without having to engage in a drawn out and very damaging austerity program.

There would clearly be ructions associated with leaving the EMU but the government would be better placed to attenuate them.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

- EMU posturing provides no durable solution

Question 2:

If policy makers use the NAIRU to compute the decomposition between structural and cyclical budget balances, then if the estimated NAIRU is above the true full employment unemployment rate, the estimated impact of the automatic stabilisers will always be biased downwards.

The answer is True.

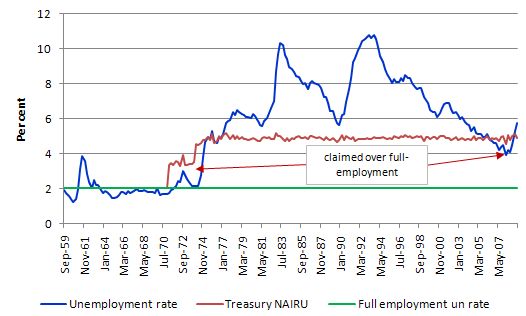

The following graph plots the actual unemployment rate for Australia (blue line) from 1959 to June 2009 and the Australian Treasury estimate of the NAIRU (red line). The data is available from the RBA.

You can see how ridiculous the estimated NAIRU is. Suddenly it jumps up just as actual unemployment rises although for such a jump to occur (according to the logic of the concept) there has to be major structural changes occurring. Historically, there is nothing that might convincingly explain that jump. Other estimation techniques give even more nonsensical estimates (they tend to just track the movement in the official unemployment rate).

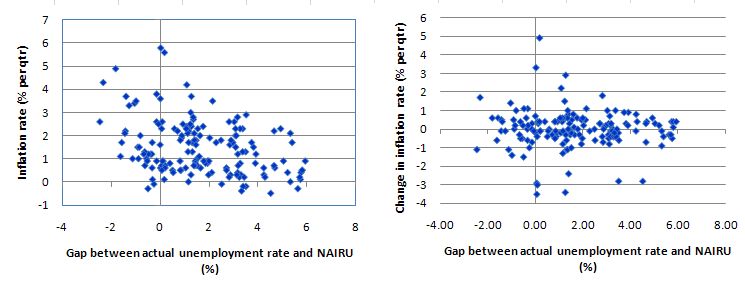

This graph show how little correspondence there is between the inflation rate and the NAIRU gap (measured as the difference between the estimated NAIRU and the actual unemployment rate). The left-panel is the actual inflation rate (vertical axis) whereas the right-panel is the change in the actual inflation rate (vertical axis). There has always been some dispute in the literature as to whether the Phillips curve (the relationship between the NAIRU gap and inflation) should be specified in terms of the actual level of inflation or the acceleration in the level.

I also tried various lags in the inflation measures (to allow for frictions) and you get the same general picture. If the mainstream economic theory was correct, then the NAIRU gap should be negatively related to inflation (whichever measure you like). That is, when the unemployment rate is above the NAIRU inflation should be falling and vice versa. The conclusion from the data is that no such relationship exists. There is no surprise in that – the NAIRU is one of the most discredited concepts in the mainstream toolkit. The problem is that governments have been significantly influenced by it to the detriment of all of us.

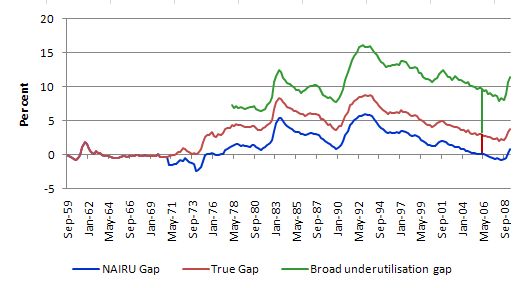

To see why this is the case, the next graph plots three different measures of labour market tightness:

- The gap between the actual unemployment rate and the NAIRU (blue line), which is interpreted as estimating full employment when the gap is zero (cutting the horizontal axis.

- The gap between the actual unemployment rate and our 2 per cent full employment rate (red line), again would indicate full employment if the line cut the horizontal axis.

- The gap between the broad labour underutilisation rate published by the ABS (available HERE), which takes into account underemployment and our 2 per cent full employment rate (green line).

The NAIRU estimates not only inflate the true full employment unemployment rate but also completely ignore the underemployment, which has risen sharply over the last 20 years.

In the June quarter 2006 the NAIRU gap was zero whereas the actual unemployment rate was still 2.78 per cent above the full employment unemployment rate. The thick red vertical line depicts this distance.

However, if we considered the labour market slack in terms of the broad labour underutilisation rate published by the ABS then the gap would be considerably larger – a staggering 9.4 per cent. Thus you have to sum the red and green vertical lines shown at June 2008 for illustrative purposes.

This means that the Australian Treasury are providing advice to the Federal government claiming that in June 2008 the Australian economy was at full employment when it is highly likely that there was upwards of 9 per cent of willing labour resources being wasted. That is how bad the NAIRU period has been for policy advice.

But in relation to this question, in June 2008, the Australian Treasury would have classified all of the federal budget balance in that quarter as being structural given that the cycle was considered to be at the peak (what they term full employment).

However, if we define the true full employment level was at 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment, then you can see that, in fact, the Australian economy would have been operating well below the full employment level and so there would have been a significant cyclical component being reflected in the budget balance.

Given the federal budget in June 2008 was in surplus the Treasury would have classified this as mildly contractionary whereas in fact the Commonwealth government was running a highly contractionary fiscal position which was preventing the economy from generating a greater number of jobs.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 3:

The fact that large scale quantitative easing conducted by central banks in Japan in 2001 and now in the UK and the USA has not caused inflation provides a strong refutation of the mainstream Quantity Theory of Money, which claims that growth in the stock of money will be inflationary.

The answer is False.

The question requires you to: (a) understand the Quantity Theory of Money; and (b) understand the impact of quantitative easing in relation to Quantity Theory of Money.

The short reason the answer is false is that quantitative easing has not increased the aggregates that drive the alleged causality in the Quantity Theory of Money – that is, the various estimates of the “money supply”.

The Quantity Theory of Money which in symbols is MV = PQ but means that the money stock times the turnover per period (V) is equal to the price level (P) times real output (Q). The mainstream assume that V is fixed (despite empirically it moving all over the place) and Q is always at full employment as a result of market adjustments.

Yes, in applying this theory they deny the existence of unemployment. The more reasonable mainstream economists (who probably have kids who cannot get a job at present) admit that short-run deviations in the predictions of the Quantity Theory of Money can occur but in the long-run all the frictions causing unemployment will disappear and the theory will apply.

In general, the Monetarists (the most recent group to revive the Quantity Theory of Money) claim that with V and Q fixed, then changes in M cause changes in P – which is the basic Monetarist claim that expanding the money supply is inflationary. They say that excess monetary growth creates a situation where too much money is chasing too few goods and the only adjustment that is possible is nominal (that is, inflation).

One of the contributions of Keynes was to show the Quantity Theory of Money could not be correct. He observed price level changes independent of monetary supply movements (and vice versa) which changed his own perception of the way the monetary system operated.

Further, with high rates of capacity and labour underutilisation at various times (including now) one can hardly seriously maintain the view that Q is fixed. There is always scope for real adjustments (that is, increasing output) to match nominal growth in aggregate demand. So if increased credit became available and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will re

The mainstream have related the current non-standard monetary policy efforts – the so-called quantitative easing – to the Quantity Theory of Money and predicted hyperinflation will arise.

So it is the modern belief in the Quantity Theory of Money is behind the hysteria about the level of bank reserves at present – it has to be inflationary they say because there is all this money lying around and it will flood the economy.

Textbook like that of Mankiw mislead their students into thinking that there is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. They claim that the central bank “controls the money supply by buying and selling government bonds in open-market operations” and that the private banks then create multiples of the base via credit-creation.

Students are familiar with the pages of textbook space wasted on explaining the erroneous concept of the money multiplier where a banks are alleged to “loan out some of its reserves and create money”. As I have indicated several times the depiction of the fractional reserve-money multiplier process in textbooks like Mankiw exemplifies the mainstream misunderstanding of banking operations. Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted home to the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply. We have regularly traversed this point. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank.

The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

So when we talk about quantitative easing, we must first understand that it requires the short-term interest rate to be at zero or close to it. Otherwise, the central bank would not be able to maintain control of a positive interest rate target because the excess reserves would invoke a competitive process in the interbank market which would effectively drive the interest rate down.

Quantitative easing then involves the central bank buying assets from the private sector – government bonds and high quality corporate debt. So what the central bank is doing is swapping financial assets with the banks – they sell their financial assets and receive back in return extra reserves. So the central bank is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the central bank). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates. This might increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop. But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly.

How these opposing effects balance out is unclear but the evidence suggests there is not very much impact at all.

For the monetary aggregates (outside of base money) to increase, the banks would then have to increase their lending and create deposits. This is at the heart of the mainstream belief is that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment. The recent experience (and that of Japan in 2001) showed that quantitative easing does not succeed in doing this.

Should we be surprised. Definitely not. The mainstream view is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But banks do not operate like this. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

Those that claim that quantitative easing will expose the economy to uncontrollable inflation are just harking back to the old and flawed Quantity Theory of Money. This theory has no application in a modern monetary economy and proponents of it have to explain why economies with huge excess capacity to produce (idle capital and high proportions of unused labour) cannot expand production when the orders for goods and services increase. Should quantitative easing actually stimulate spending then the depressed economies will likely respond by increasing output not prices.

So the fact that large scale quantitative easing conducted by central banks in Japan in 2001 and now in the UK and the USA has not caused inflation does not provide a strong refutation of the mainstream Quantity Theory of Money because it has not impacted on the monetary aggregates.

The fact that is hasn’t is not surprising if you understand how the monetary system operates but it has certainly bedazzled the (easily dazzled) mainstream economists.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Islands in the sun

- Operation twist – then and now

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 4:

The central bank could always use quantitative easing to control interest rates at any maturity along the yield curve if it desired. The only thing stopping it are political constraints.

The answer is False.

The question deliberately confused two distinct concepts in central bank operations to test whether you understood each of them.

The aim of quantitative easing is the increase the size of the central bank’s balance sheet and the techniques used are explained above in the discussion relating to Question 3.

Conversely, a policy aiming to control interest rates at any maturity along the yield curve is about changing the composition of the central bank’s balance sheet by systematically purchasing, for example, long-term bonds as a means of controlling long-term yields.

The two policies clearly influence long-term rates but the logic and impact on bank reserves is quite different.

Please read my blog – – for more discussion on this point.

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Operation twist – then and now

Question 5:

Central bank balance sheet management aimed at controlling the yields on public debt at all maturities may not have much impact on the term structure during periods of high inflation.

The answer is True.

I was going to use the term “economic impact” but decided against that because it might be misleading given that it would require a discussion of what an economic impact actually is. I consider an economic impact has to involve a discussion of the real economy rather than just the financial dimensions.

In that context you would then have had to consider two things: (a) the impact on private interest rates; and (b) whether interest rates matter for aggregate demand. And in a simple dichotomous choice (true/false) that becomes somewhat problematic.

I chose the alternative “impact on the term structure” because it didn’t require any consideration of the real economy but only the impact on private interest rates.

The “term structure” of interest rates, in general, refers to the relationship between fixed-income securities (public and private) of different maturities. Sometimes commentators will confine the concept to public bonds but that would be apparent from the context. Usually, the term structure takes into account public and private bonds/paper.

The yield curve is a graphical depiction of the term structure – so that the interest rates on bonds are graphed against their maturities (or terms).

The term structure of interest rates provides financial markets with a indication of likely movements in interest rates and expectations of the state of the economy.

If the term structure is normal such that short-term rates are lower than long-term rates fixed-income investors form the view that economic growth will be normal. Given this is associated with an expectation of some stable inflation over the medium- to longer-term, long maturity assets have higher yields to compensate for the risk.

Short-term assets are less prone to inflation risk because holders are repaid sooner.

When the term structure starts to flatten, fixed-income markets consider this to be a transition phase with short-term rates on the rise and long-term rates falling or stable. This usually occurs late in a growth cycle and accompanies the tightening of monetary policy as the central bank seeks to reduce inflationary expectations.

Finally, if a flat terms structure inverts, the short-rates are higher than the long-rates. This results after a period of central bank tightening which leads the financial markets to form the view that interest rates will decline in the future with longer-term yields being lower. When interest rates decrease, bond prices rise and yields fall.

The investment mentality is tricky in these situations because even though yields on long-term bonds are expected to fall investors will still purchase assets at those maturities because they anticipate a major slowdown (following the central bank tightening) and so want to get what yields they can in an environment of overall declining yields and sluggish economic growth.

So the term structure is conditioned in part by the inflationary expectations that are held in the private sector.

It is without doubt that the central bank can manipulate the yield curve at all maturities to determine yields on public bonds. If they want to guarantee a particular yield on say a 30-year government bond then all they have to do is stand ready to purchase (or sell) the volume that is required to stabilise the price of the bond consistent with that yield.

Remember bond prices and yields are inverse. A person who buys a fixed-income bond for $100 with a coupon (return) of 10 per cent will expect $10 per year while they hold the bond. If demand rises for this bond in secondary markets and pushes the price up to say $120, then the fixed coupon (10 per cent on $100 = $10) delivers a lower yield.

Now it is possible that a strategy to fix yields on public bonds at all maturities would require the central bank to own all the debt (or most of it). This would occur if the targeted yields were not consistent with the private market expectations about future values of the short-term interest rate.

If the private markets considered that the central bank would stark hiking rates then they would decline to buy at the fixed (controlled) yield because they would expect long-term bond prices to fall overall and yields to rise.

So given the current monetary policy emphasis on controlling inflation, in a period of high inflation, private markets would hold the view that the yields on fixed income assets would rise and so the central bank would have to purchase all the issue to hit its targeted yield.

In this case, while the central bank could via large-scale purchases control the yield on the particular asset, it is likely that the yield on that asset would become dislocated from the term structure (if they were only controlling one maturity) and private rates or private rates (if they were controlling all public bond yields).

So the private and public interest rate structure could become separated. While some would say this would mean that the central bank loses the ability to influence private spending via monetary policy changes, the reality is that the economic consequences of such a situation would be unclear and depend on other factors such as expectations of future movements in aggregate demand, to name one important influence.

Just a query regarding the unemployment/NAIRU gap versus the inflation rate. Wouldn’t the entrenched inflation Australia saw between the Whitlam era until the recession we had to have simply be a product of an inflexible labour market?

I was under the impression that during this time the primary cause of the entrenched inflation was the result of powerful unions who could exert large wage rises (legitimately or not). The inflation caused initially by the oil crisis in the 70s should have been quelled by the early 80s recession (as it was in the US which a more flexible labour market). However in places like Australia and the UK with more powerful unions and less flexible labour markets the inflation remained throughout the 80s. In Australia at least it took until the recession we had to have to finally lock in low inflation.

As a result, the inflation versus NAIRU gap analysis over the last 40 years would not be comparing apples with apples due to the difference in labour market flexibility between the modern era (post Keating and Howard reforms) and the 70s and 80s during the period of high entrenched inflation and rampant militant unionism who were able to weild real power.

Dear Bill, Still on NAIRU, you often suggest that the whole NAIRU idea is flawed and that a much higher level of aggregate demand is possible than most economists believe to be possible. Can you do a post on this sometime, because I’m not convinced? Or is there an old post that concentrates on this question?

I have what is probable a stupid question about this statement:

“In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve.”

Can someone explain to me or point out where I can find an explanation of the mechanism by which increasing the central bank’s demand for “long maturity” assets reduces interest rates?

In open market operations the purchase of government bonds and other securities increases the supply of reserves by exchanging securities for reserves. This increased supply leads to a decrease in the price of reserves (the interest rate; the effective federal funds rate if I’m not mistaken). I guess all this is considered short-term stuff. What I’m not clear on is how interest rates are determined in the long term. Normally, when the demand for something increases its price increases as well. But here an increase in the demand for long term assets (mostly mortgaged backed securities if I am not mistaken) is said to lead to a decrease in the price of those assets. What am I missing?

More questions about Quantitative Easing:

“So the central bank is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the central bank). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.”

It is my understanding that mark-to-market rules were suspended in the period before the Federal Reserve committed to purchasing mortgage backed securities from commercial and investment banks. Many of the mortgages in these mortgage backed securities have been described as “toxic” in the mainstream media. That is, not worth very much at all under mark-to-market rules. But the sale of these securities to the FRB were outright sales, no? If these mortgage backed securities were sold at book value, not market value, wouldn’t the sale have increased the amount of reserves held by private banks by the amount they would have had to mark down their mortgage backed security assets? Maybe this doesn’t have anything to do with quantitative easing directly, but it seems to me the decision by the Federal Reserve to purchase the mortgage backed securities at book-value increased the reserves of private banks. Whether or not the increase in reserves will lead to inflation is another story. After reading the blog post “Building Bank Reserves is not Inflationary,” I think I understand why increasing reserves is not inflationary, but I may have some more questions later.

One last thing. I am planning on purchasing and reading an accounting text over the summer when I have time off from work, but as of this moment I know almost nothing about the subject. If I am misusing the terms “mark-to-market,” and “book value,” I apologize and would appreciate any correction. The point I was trying to convey is there is a sense out in the blogosphere and even the mainstream media that the Federal Reserve overpaid for the mortgage backed securities they purchased from private banks. My point was to the extent the Federal Reserve overpaid for these assets private bank reserves were increased. This constitutes a change in net-financial assets as the reserves held by private banks at their federal reserve member banks count as assets of the private banks and liabilities of the Central Bank. If this is wrong I would appreciate an explanation why. Thank you.

@ nklein

(I am a complete noob at this stuff, but I am going to have a bash – it seems about my level ) 🙂

—- bonds and interest

I think you have missed the difference between the price of a bond and its effective interest rate; they are opposites. A bond represents a fixed stream of income, so the more you pay for that income stream (the bond price) the less interest you are getting on the money you put in.

Or think of it this way. The guy who owns the bond is the *lender*, not the borrower. More demand for bonds = more people wanting to lend = lower interest.

—- mortgages and reserves

The government buying of junk mortgages had nothing to do with quantative easing, and Bill is talking about net financial assets, not net reserves. Reserves (like cash) are a financial asset, but most financial assets (like loans) are not reserves. The gov buys bank assets *by* increasing bank reserves (that’s the only way the government buys anything) and their book value is irrelevant.

QE, on the other hand, is where the government buys more long-term assets than it sells, and allthough mortgages are indeed long-term assets there was nothing stopping the gov from selling ordinary long-term debt at the same time and ‘sterilising’ the effect. So the the decision to QE is independent of the decision to buy junk or the price they paid for it.

More importantly, read Bill’s page on why QE is basically bunk (summary : reserves are set by the banks and have no effect on lending ) – http://goo.gl/udpi

By definition the government overpaid for those mortgages; if the bank could have sold them for as much on the market it would already have done so. So the blogosphere is right on this one.

The difference between the book value and what the gov paid is the change in the banks net financial assets (loans + reserves). If the gov paid book value then there was no change in bank net assets at all, which was the whole point of the exercise. But whatever the gov paid for them was exactly the increase in the bank’s reserves, book value had nothing to do with it.

Dear Bill,

I just wanted to sincerely thank you for putting together this blog. I am currently an undergraduate at Harvard, studying economics, and have been continually frustrated at the refusal of professors/TFs to explain some of even the most basic faulty assumptions endemic to their work (Martin Feldstein & Social Security, Mankiw & wages, Barro and growth…the list goes on and on).

I have taken courses from some of the most “respected” names in economics, and none of them, NONE, have even come close to presenting an explanatory framework of the world today as robust or coherent as yours. I have learned more from obsessively reading your blog in the past week than I have in now four years of Harvard economics.

I would beg you to serve as a visiting professor here, if only to try and counter the brainwashing of impressionable economics undergraduates (the only “saltwater” economist left here was barred from teaching undergraduates in my sophomore year), but the weather is shit, and the people shittier.

So, thank you!

Hi, Billy, I just mentioned your blog in my recent post Blogs and Web Sites you may want to follow. Mention: “… so far, and probably forever, the prize goes to Billy for economic views most contradicting those of CrisisMaven! And therefore a must-read.” For your own investigative work you may also want to check out my Statistical Reference List with links to hundreds of thousands of statistics, indicators, time lines etc.

Thanks begruntled. My first question was definitely stupid. I should have just read down to question five to see the price and interest rate of a bond are inversely related. I knew that anyway. I liked your explanation for my second question too. Thank you again.

Dear HarvardUndergraduate

Thanks for your comment it is appreciated.

I am sorry your learning experience has been so bleak. But with the assembled cast that you have been subjected to it is little wonder. But thinking positively, it is a great thing that you are thinking outside of the prison they have set out for you and you will come out of your time as an undergrad in much better shape than those who have never been able to escape and understand different ways of thinking.

All the best.

bill

Dear Ralph

I cover the issues in this blog The dreaded NAIRU is still about!. My book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned provides a comprehensive academic critique of the NAIRU. It is available via google book (in part).

best wishes

bill

Dear Rationalist

Thanks for your comment. The question is a good one.

You said:

The entrenched inflation was the result of a combination of things. Remember that money wage push cannot cause inflation. The initial shock came from the OPEC oil price rises which then imposed real costs on the economy that had to be borne by one or more of the distributional groups. The unions wanted to preserve real wages and capital wanted to preserve real margins. That is a recipe for a competing claims distributional struggle over real output which is what happened. Both sides of the struggle, for a time, had the power to push their own nominal claims and react to the other side’s push. So it was much more than an “inflexible” labour market.

It is also clear that the inflation persisted into the 1980s but was stable not accelerating. The 1991 recession killed the remaining inflationary expectations and we haven’t had a problem since.

I have sympathy with your position that their has been regime shifts in terms of the capacity of workers to defend (or push) their real wage claims. Certainly now it is easier for firms to dismiss workers than it was in the 1970s. It was in that context that I mentioned the labour market has changed and now underemployment is doing some of the “wage disciplining” that unemployment used to do on its own. The latter is still the most powerful constraint on wage demands but the former is catching up.

But we still should see some relationship between the NAIRU gap and inflation (or the change in inflation) over the period shown – perhaps shifting as the regime has changed. But there is no discernible relationship which suggests the estimation of the NAIRU is screwy.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill for the reply and your explanation.

I am also curious if there is a simple explanation for why the US had such good outcomes from the early 80s recession in terms of locking in low stable inflation when compared to Australia and the UK? Was it simply a structural thing or a difference in monetary policy? Or was it more complex than any of this/still up for debate?

Bill,

re: NAIRU

That is a nice argument that the NAIRU is incorrect. The whole NAIRU concept is flawed, of course, but I wonder whether you have a replacement — i.e. is the criticism just one that NAIRU is set too high, and should be 2%, or are you arguing that the relationship between inflation and unemployment is fundamentally different?

re: “public” term structures being disconnected from “private” term structures,

I see some progress here, but still you are arguing that an investor will purchase two assets with the same capital commitment but different expected returns. Why would anyone do this? All returns compete with each other. Moreover, there does not (yet) seem to be an awareness that capital is endogenous, so when it is too expensive, more can be supplied, lowering the yield. So, to clarify are you arguing that

1. Capital is exogenous, or

2. Yield is not a function of the return on capital