I am travelling today to Tokyo and have little time to write here. But with…

Australia national accounts – stronger economic growth in June-quarter 2025

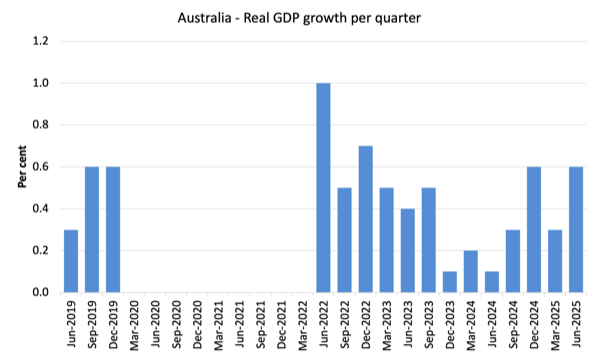

The Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest – Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, March 2025 – today (September 3, 2025), which shows that the Australian economy grew by 0.6 per cent in the June-quarter 2025 (up from 0.2 per cent) and by 1.8 per cent (up from 1.3) over the 12 months. GDP per capita growth turned positive after several consecutive negative quarters. Household consumption expenditure growth strengthened and led the strong growth in domestic demand. Overall, a surprisingly robust result.

The main features of the National Accounts release for the June-quarter 2025 were (seasonally adjusted):

- Real GDP increased by 0.6 per cent for the quarter (0.2 per cent last quarter). The annual growth rate was 1.8 per cent (1.3 last quarter).

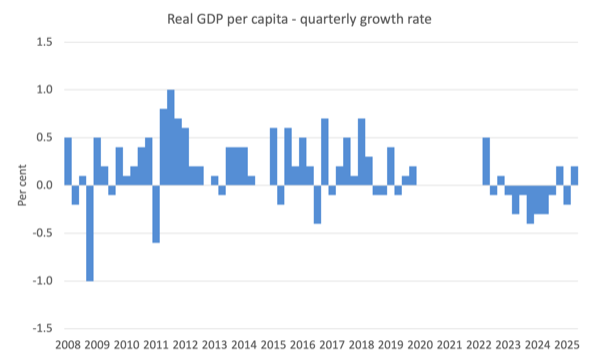

- GDP per capita rose 0.2 per cent (-0.2 per cent last quarter) and 0.2 per cent for the year – an improvement.

- Australia’s Terms of Trade fell 1.1 per cent for the quarter and -2.4 per cent over the 12 month period.

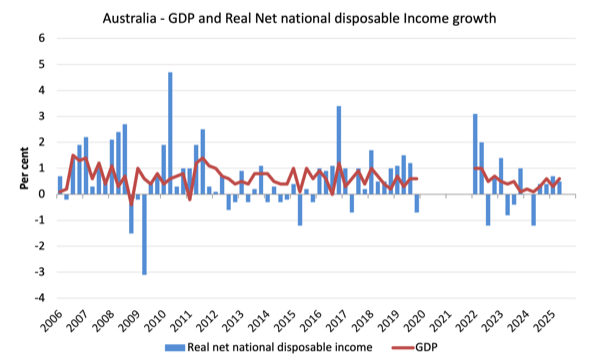

- Real net national disposable income, which is a broader measure of change in national economic well-being, rose by 0.5 per cent for the quarter (0.6 last quarter) and 2.1 per cent over the 12 months – an improvement.

- The Household saving ratio (from disposable income) fell to 4.2 per cent from 5.2 per cent.

Overall growth picture – growth rate much stronger than in recent past

The ABS – Media Release – said that:

Australian gross domestic product (GDP) rose 0.6 per cent in the June quarter 2025 … and 1.8 per cent compared to a year ago …

Economic growth rebounded in the June quarter following subdued growth in the March quarter, which was heavily impacted by weather events …

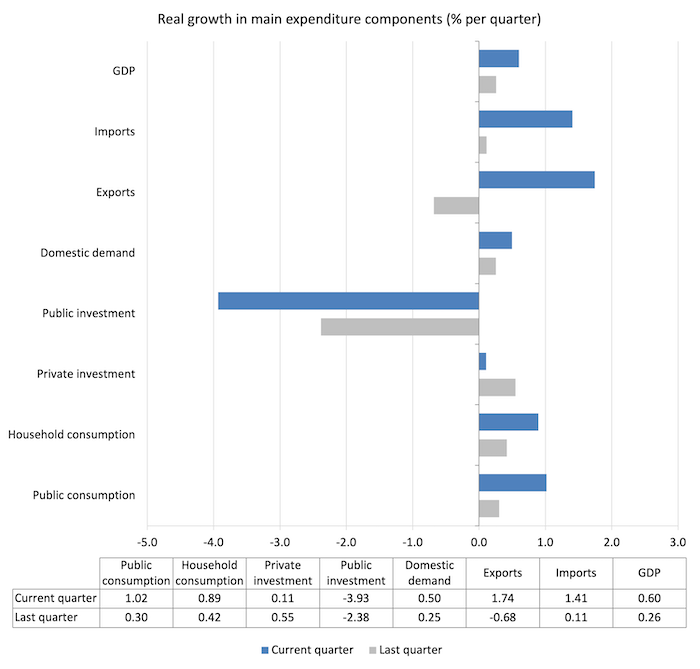

Domestic final demand was the main driver of growth led by household and government spending. Public investment was the largest detractor from growth.

Net trade also contributed to GDP growth, led by exports of mining commodities.

GDP per capita increased 0.2 per cent this quarter, following a decrease in the March quarter …

Public investment fell 3.9 per cent and was the largest detractor from growth. Excluding the Covid period, this was the largest fall since September 2017 …

Government final consumption expenditure rose 1.0 per cent in the June quarter …

The household saving to income ratio fell to 4.2 per cent in the June quarter from 5.2 per cent in the March quarter.

The short story:

1. The weakness in private domestic demand that has been a feature of the last few years reversed in the June-quarter, with the continuing return to stronger household consumption expenditure – up 0.9 per cent.

2. The large State government infrastructure projects in transport and health are unwinding, which largely explains the decline in public sector investment expenditure.

3. Government consumption expenditure rose, in part, because of the expenditure associated with the May federal election.

4. The household saving ratio fell because the growth in nominal household spending (1.5 per cent) outstripped the growth in disposable income (0.6 per cent).

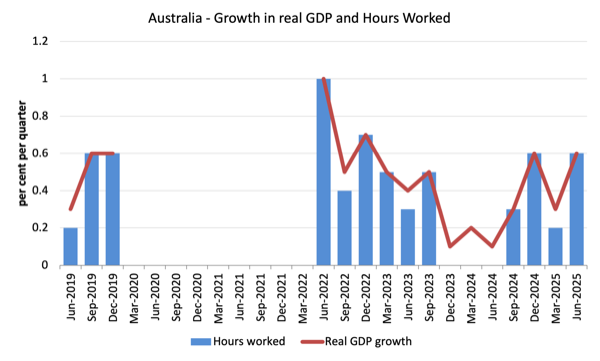

The next graph shows the quarterly growth over the last five years with the extreme observations during the worst part of the COVID restrictions and government income support taken out.

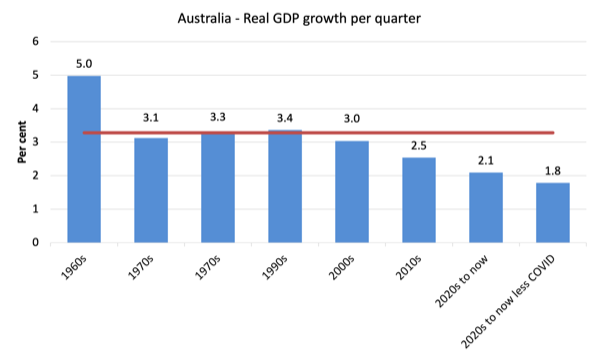

To put this into historical context, the next graph shows the decade average annual real GDP growth rate since the 1960s (the horizontal red line is the average for the entire period (3.28 per cent) from the June-quarter 1960 to the June-quarter 2025).

The 2020-to-now average has been dominated by the pandemic.

But as the previous graph shows, the period after the major health restrictions were lifted generated lower growth compared to the period when the restrictions were in place.

If we take the observations between the December-quarter 2020 and the December-quarter 2022 out, then the average since 2020 has been 1.8 per cent per annum.

It is also obvious how far below historical trends the growth performance of the last 2 decades have been as the fiscal surplus obsession has intensified on both sides of politics.

Even with a massive household credit binge and a once-in-a-hundred-years mining boom that was pushed by stratospheric movements in our terms of trade, our real GDP growth has declined substantially below the long-term performance.

The 1960s was the last decade where government maintained true full employment.

GDP per capita improves

In the June-quarter 2025, GDP per capita grew by 0.2 per cent and putting an end to the speculation of a renewed GDP per capita recession.

While commentators focus on this statistics, the meaning of the average is questionable, given the highly skewed income distribution towards the top end.

What we can say is that if the average is declining, then those at the bottom are doing it very tough indeed.

The following graph of real GDP per capita (which omits the pandemic restriction quarters between December-quarter 2020 and December-quarter 2021) tells the story.

Analysis of Expenditure Components

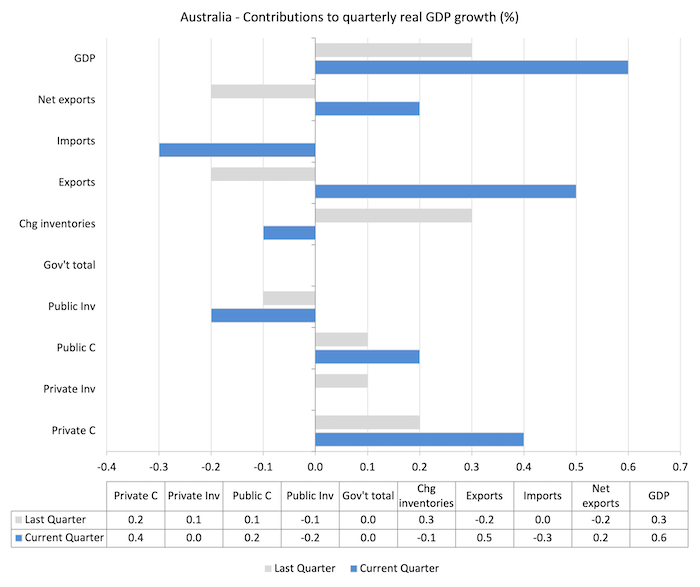

The following graph shows the quarterly percentage growth for the major expenditure components in real terms for the March-quarter 2025 (grey bars) and the June-quarter 2025 (blue bars).

- Household consumption expenditure growth accelerated.

- Export growth outstripped import growth – so net exports were positive.

- The government sector expenditure – consumption rose while capital fell.

Contributions to growth

The following bar graph shows the contributions to real GDP growth (in percentage points) for the main expenditure categories. It compares the June-quarter 2025 contributions (blue bars) with the previous quarter (gray bars).

- Household consumption expenditure added 0.4 points (up from 0.2 points).

- Private investment expenditure added nothing (down from 0.1).

- Net exports added 0.5 points (up from -0.2) – the 0.5 point export contribution outweighed the -0.3 points import subtraction (remember positive import expenditure growth constitutes a loss of growth).

- Overall government contribution was zero – the recurrent contribution (0.2 points) offsetting the capital contraction (-0.2 points).

Material living standards rose 0.5 points in the June-quarter

The ABS tell us that:

A broader measure of change in national economic well-being is Real net national disposable income. This measure adjusts the volume measure of GDP for the Terms of trade effect, Real net incomes from overseas and Consumption of fixed capital.

While real GDP growth (that is, total output produced in volume terms) rose by 0.6 per cent in the June-quarter, real net national disposable income growth rose by 0.5 per cent.

How do we explain that?

Answer: The terms of trade were negative in the June-quarter but we offset somewhat by the rise in compensation of employees (COE).

In per capita terms, real net national disposable income improved by a small margin (0.11 per cent) for the quarter and by 0.39 per cent over the year.

Since the March-quarter 2022 (when the restrictions starting relaxing), the decline has been 2.9 per cent.

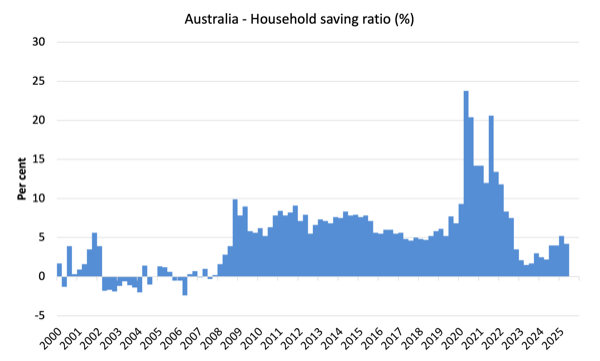

Household saving ratio fell by 1 point to 4.2 per cent

The RBA tried to wipe out the household saving buffers as it hiked interest rates hoping that this would reduce the likelihood of recession.

Of course, that process attacked the lower-end of the wealth and income distribution, given the rising interest rates have poured millions into those with interest-rate sensitive financial assets.

Households then became cautious – reducing overall expenditure growth and increasing their saving out of their disposable income.

That behaviour changed again this quarter with spending growth outstripping the growth in disposable income.

The following graph shows the household saving ratio (% of disposable income) from the December-quarter 2000 to the current period.

It shows the period leading up to the GFC, where the credit binge was in full swing and the saving ratio was negative to the rise during the GFC and then the most recent rise.

An increasing saving ratio provides the household sector overall with an increased capacity to risk manage in the face of uncertainty.

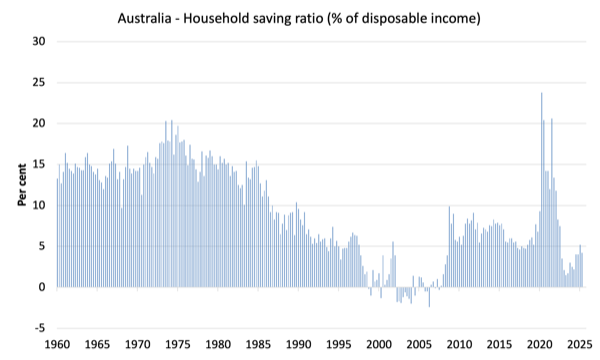

The next graph shows the saving ratio since 1960, which illustrates the way in which the neoliberal period has squeezed household saving.

Going back to the pre-GFC period, the household saving ratio was negative and consumption growth was maintained by increasing debt – which is an unsustainable strategy given that household debt is so high.

Even though the ratio has been rising slightly in recent quarters, it is still well below past levels.

The following table shows the impact of the neoliberal era on household saving. These patterns are replicated around the world and expose our economies to the threat of financial crises much more than in pre-neoliberal decades.

The result for the current decade (2020-) is the average from June 2020.

| Decade | Average Household Saving Ratio (% of disposable income) |

| 1960s | 14.4 |

| 1970s | 16.2 |

| 1980s | 11.9 |

| 1990s | 5.0 |

| 2000s | 1.4 |

| 2010s | 6.6 |

| 2020s on | 8.6 |

| Since RBA hikes | 3.5 |

Slight gain in productivity growth

Real GDP rose 0.6 points in the quarter, matching the growth in working hours.

Which means that GDP per hour rose slightly (0.1 per cent on rounding).

The modest growth in labour productivity end three consecutive quarters of declining productivity growth.

The ABS released more detailed productivity growth data this quarter, which will allow us to be more precise in terms of understanding which sectors are contributing to the malaise.

I will provide a separate analysis of it once I have fully understood the new framework.

But the evidence to date is that productivity growth in the:

- Market sector – 0.3 per cent (annual), 0.49 per cent (quarter).

- Non-market sector – minus 0.1 per cent (annual), 0.42 per cent (quarter).

- Overall – 0.1 per cent (annual), 0.3 per cent (quarter).

The following graph presents quarterly growth rates in real GDP and hours worked using the National Accounts data for the last five years to the June-quarter 2025.

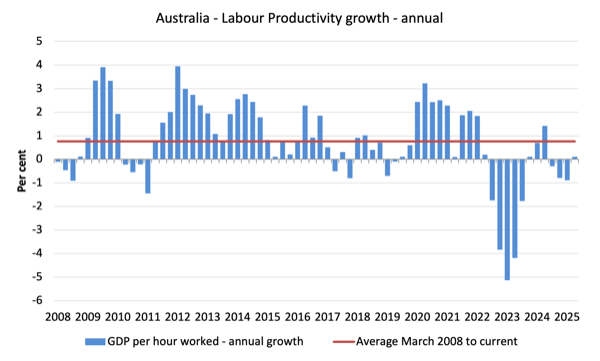

To see the above graph from a different perspective, the next graph shows the annual growth in GDP per hour worked (labour productivity) from the beginning of 2008 to the June-quarter 2025.

The horizontal red line is the average annual growth since the June-quarter 2008 (0.77 per cent), which itself is an understated measure of the long-term trend growth of around 1.5 per cent per annum.

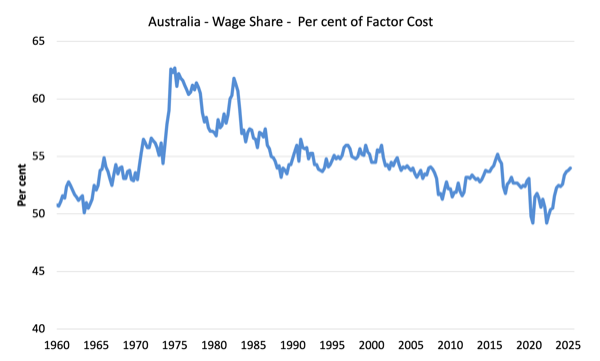

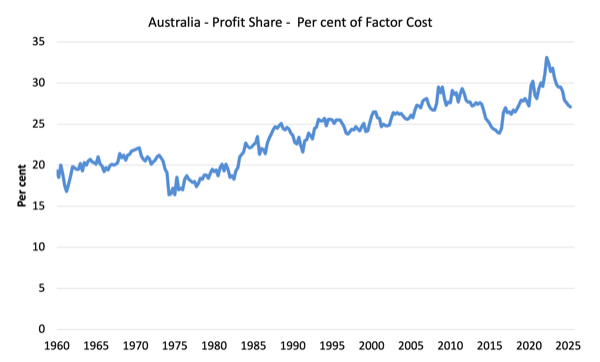

The distribution of national income – wage share rose

The wage share in national income rose 0.2 points to 54 per cent in the June-quarter 2025.

It hasn’t been that high since the September-quarter 2016.

The profit share fell to 27.1 per cent (down 0.2 points).

The residual is largely the government share.

The first graph shows the wage share in national income while the second shows the profit share.

The declining share of wages historically is a product of neoliberalism and will ultimately have to be reversed if Australia is to enjoy sustainable rises in standards of living without record levels of household debt being relied on for consumption growth.

Conclusion

Remember that the National Accounts data is three months old – a rear-vision view – of what has passed and to use it to predict future trends is not straightforward.

The Australian economy grew by 0.6 per cent in the June-quarter 2025 (up from 0.2 per cent) and by 1.8 per cent (up from 1.3) over the 12 months.

GDP per capita growth turned positive after several consecutive negative quarters.

Household consumption expenditure growth strengthened and led the strong growth in domestic demand.

Overall, a surprisingly robust result.

Clarification on terminology

I advocated a degrowth strategy for the global economy overall given that our footprint is 1.7 times the capacity of the biosphere to regenerate.

To achieve that strategy, given that many poorer nations must continue to grow, will require rather substantial cut backs in spending and consumption in the richer nations.

When I analyse the National Accounts data or any expenditure/output data, I write as if growth is ‘good’.

But that terminology is used in the context that without economic growth and without any substantial shifts in income distribution and government transition policies, trying to pursue a recessionary strategy would damage the weakest members of our society disproportionately.

In some respects, I am abstracting from the damaging reality of our ecological footprint.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill – off-topic but thought you’d be interested

The UK Green party elected a new leader this week, Zach Polanski. He was interviewed briefly on BBC TV last night.

Needless to say, the interviewer asked him “How are you going to pay for all your promises, given the UK’s humongous national debt and record borrowing costs. Won’t you quickly lose the confidence of the City?”

To my amazement, Mr. Polanski replied, “The government is not like a household…The UK government issues its own currency so doesn’t really have to borrow…”

The interviewer paused, unsure how to proceed, and seemed to think he was avoiding answering her question but soon moved on to other topics.

At last, the glimmer of a possible breakthrough in the mainstream discourse, at least in the UK. He’s also been in touch with Jeremy Corbyn and there’s talk of a grand alliance forming on the left of British politics in future.

The English and Welsh Green Party had adopted the “Positive Money” fractional reserve banking approach to inform its monetary policy, at least until recently.

I know some Greens are better informed on MMT – including Caroline Lucas, less directly influential these day, but if Zack Polanski is economically literate, that could be a very helpful influence.

The issue then becomes how MMT informs future Green policy – especially regarding the monetary straitjacket exerted by the BoE.

A Green commitment to full employment (both quantitatively and qualitatively) as the central macroeconomic goal instead of a 2% inflation target would be interesting.

As Bill posted very recently, we used to think of full employment as 98%.

Neil says:

“ Anything with an interest rate can be treated as having a present value. The interest rate acts as a government funded import subsidy over the tax credit value. Take away that subsidy and there will be a notional shift. However there is necessarily an equivalent reduction in the supply of tax credits as interest payments cease, which makes the underlying tax credit more valuable (ie a ‘cut in government spending’). Where’s the new indifference point?”

What is your view Bill?

Bill, thanks

I also read the ‘economic’ commentary in the Guardian and find it all pretty much lame.

Mostly apologists for a fairly broken and corrupt economic system; the Economy seems to me to be Their Economy.

Apparently things are on the up, and I wonder: how can that be when the fundamental economy, the biosphere, continues to go down the dunny at an alarming rate?

I am looking forward to Thea Riafrancos’ book Extraction: The Frontiers of Green Capitalism to see her take. https://www.theariofrancos.com/extraction

Ciao 4 Now