I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

One hell of a juxtaposition

Tonight we consider the tale of two countries with some other snippets of good taste included for interest. In the last few days the Japanese government has announced the largest fiscal stimulus in its modern era (since records have been kept) while Ireland announced its 2010 budget which has been characterised as the harshest in the republic’s history. Both countries are mired in recession with only the most modest signs of any recovery. So on the face of it this is one hell of a juxtaposition. What gives?

Yesterday’s UK Times newspaper (December 26, 2009) presented economic commentary that was stark in its juxtaposition. Without noting the underlying issues that connected the articles, the Times reported that the:

… new Japanese Prime Minister, has stunned a nation already mired in huge public debt by unveiling the country’s biggest ever postwar budget … aimed at “saving people’s lives”.

and that:

Ireland, the first eurozone nation to enter recession, is struggling to emerge from beneath a blizzard of frighteningly negative economic statistics after Brian Lenihan, the Finance Minister, delivered a stinging Budget this month with a target of cutting €4 billion (£3.6 billion) in spending …

So on the one hand, it is fortunate that there is fiscal leadership in Japan and the capacity to implement it.

But on the other hand, the Irish do not have the willingness to provide fiscal leadership in their winter of recession which might reflect the voluntary constraints they have imposed on their fiscal capacity courtesy of their EMU membership.

So perhaps the best advice to the Irish is to catch the ferry – although that might no longer be the boon it has historically represented. In the past the Irish could find better labour market opportunities in Britain and they left in droves. Now, with the lack of fiscal leadership in Britain one wonders whether life there would be better these days.

But for the Irish things are very bleak indeed.

The Times article on Japan – Debt-laden Japan shocked by £630bn spree to save lives’ reports that

Yukio Hatoyama, the new Japanese Prime Minister, has stunned a nation already mired in huge public debt by unveiling the country’s biggest ever postwar budget: a 92.3 trillion yen (£630 billion) spending spree aimed at “saving people’s lives”.

The unprecedented budget, which supposedly shifts Japan’s fiscal spending focus “from concrete to lives”, comes amid rising concern about the solidity of sovereign debt in the world’s second-largest economy.

The new budget will require additional debt issuance of Y44.3 trillion – within the Government’s expected band, but still at a level that will raise Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio to nearly 195 per cent.

First, it only requires the additional debt issuance because the Japanese government legislates that it continues gold standard practices that are totally unnecessary in a fiat monetary system.

Second, the rising debt is a safe place for the Japanese to park their savings and provides them with an income flow. The domestic bond market in Japan is “very loyal” and the Bank of Japan never has trouble placing public debt into the bond markets. What is not often understood about Japan is that there is no formal superannuation system so people save for their own futures.

Third, there is no risk of sovereign debt default in Japan. Zero. Even putting this into a paragraph which followed references to “mired in huge public debt” shows the ideological nature of the journalist and the fact that they do no understand the first principles of a modern monetary economy (or choose to display the ignorance to advance the former).

The conservative analysts are all scurrying about noting that it is the first time since the Second World War that “new debt issuance has exceeded tax revenues” which just tells me how deep the recession has been in Japan and nothing more than that. You can imagine the debt-armageddon scenarios that are going about at present in Japan. I suppose it keeps people busy dreaming up this nonsense.

Fourth, the interesting part of the story is that there is now a discrete policy shift going on as a result of the political changes in Japan that arose from the last election – that is, the ascendency of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ).

The shift will see the government reduce its obsession with public infrastructure development as a vehicle for huge fiscal injections and instead put the spending power into poor households. The Times said:

Mr Hatoyama swept to power in August with grand promises that the era of wasteful public spending would end. Japan’s unnecessary and notoriously expensive “roads to nowhere” public works projects would be curtailed and the money diverted to supporting beleaguered households … The budget plan will contain Y53.4 trillion in policy spending; 51 per cent of that will go to social security programmes. This is the first time that social security has received more than half of policy spending, reflecting the new Government’s focus on jump-starting consumption rather than the big public works projects carried out by former administrations.

Many mainstream economists have been calling for a consumption tax rise to repair the fiscal hole. Yes, what hole? Others have been saying that there should be less government spending and more tax cuts. Hatoyama had promised tax cuts to businesses during the election but appears to have reneged on that.

The debate about the relative merits of tax cuts and spending increases to stimulate a badly recessed economy has been growing over the last year – and it is not confined to Japan. The issue comes down to the relative magnitudes of public spending and tax multipliers.

The usual analysis is that government spending multipliers are more expansionary (larger multipliers) than cutting taxes because some of the tax cut is saved while all of the spending is injected into the demand stream. It is a conclusion that is consistent with modern monetary theory (MMT).

Of-course, the neo-liberal bias is towards tax cuts (supported with obvious rhetoric such as “empowering individuals”) rather than government spending (“more socialism”). Last year, Greg Mankiw, contrary to what he requires students to learn in his (terrible) textbook, seemed to come around to the argument that tax cuts are more expansionary.

He said:

My advice to Team Obama: Do not be intellectually bound by the textbook Keynesian model. Be prepared to recognize that the world is vastly more complicated than the one we describe in ec 10. In particular, empirical studies that do not impose the restrictions of Keynesian theory suggest that you might get more bang for the buck with tax cuts than spending hikes.

He also quotes several studies in support of this claim. Unfortunately, each one of them is either inapplicable to the current situation or he misquotes the study. On one such study, Mankiw says that “recent research by Christina Romer and David Romer looks at tax changes and concludes that the tax multiplier is about three: A dollar of tax cuts raises GDP by about three dollars”. Other writers have investigated this point and rejected Mankiw’s interpretations.

For example, DeLong who has investigated the matter (and spoken personally with one of the Romers) says:

It is somewhat puzzling that Mankiw appears to believe that the Romers do think that tax multipliers are larger than spending multipliers, as they do not, and this is something that he could have very easily checked.

In fact, the Romers’ article “does not distinguish between the two, referring only to the “substantial multiplier … due to the procyclical behavour of investment”.

The pro-tax findings rely on the tax cuts stimulating investment (capital formation) by easing interest rates and/or business charges and further assume that spending increases drive interest rates up. Besides many other questionable methodological issues in the papers, the mainstream assumption that budget deficits drive up interest rates and crowd out investment are just plain wrong in a modern monetary economy.

If you don’t believe me – please explain Japan! Japan is my favourite complex and complete (fully-specified) non-linear dynamic economic model with full stock-flow accounting consistency. It saves me having to muck around with Matlab or whatever using highly simplified models due to tractability constraints!

Anyway, at a time when the Japanese economy is still beset with deflation and historically high unemployment rates (although only just over 5 per cent), the government is displaying strong fiscal leadership.

It has assessed that it is better to direct public spending at the poor (who will likely spend more as a percentage of their marginal income than others) rather than continue the tradition of large public works programs in a nation that risks concreting itself over.

The important point is that it recognises its on-going role to plug the spending gap left by non-government saving (and the export collapse) and it recognises it has the capacity as a sovereign issuer of its own currency to run large deficits. In this sense, the Japanese government is placing a premium on keeping unemployment low and is resisting the mainstream pressures (from analysts, credit rating agencies, etc) to cut back the deficit.

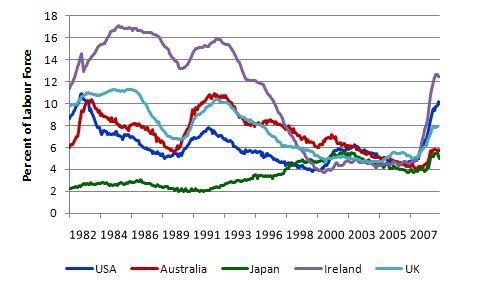

The following graph shows seasonally adjusted monthly unemployment rates for the US, Australia, Japan, Ireland and the UK from January 1982 to November 2009 (using official data from the relevant national statistical offices).

Even though Japan has been through one of its worst economic downturns, the unemployment rate is just above 5 per cent and is falling. Australia, the so-called best performer of this group in terms of GDP growth rates etc (it resisted a “technical” recession) still cannot manage to get our official unemployment rate below Japan, which has been mired in recession.

The experience of the US, UK and Ireland in this context also stands out. And it is to Ireland that I turn next.

The experience of Ireland is almost diametrically opposed to that of Japan. The Times article Celtic Tiger finished off by debunked ‘miracle’ reports that “Brian Lenihan, Finance Minister of Ireland, delivered a stinging Budget” for 2010.

Here is the full Irish Budget if you are interested.

The Times reports that:

The worst Christmas in the history of the modern independent Irish State? … many are wondering if 2010 can be any worse than the outgoing year.

For the nation’s public sector workers, pay next month will reflect cuts of between 5 per cent and 20 per cent, levels of reduction not experienced since the 1920s, even when not taking into account previous levies imposed since the Celtic Tiger economic “miracle” began unravelling a year ago.

Ireland, the first eurozone nation to enter recession, is struggling to emerge from beneath a blizzard of frighteningly negative economic statistics after Brian Lenihan, the Finance Minister, delivered a stinging Budget this month with a target of cutting €4 billion (£3.6 billion) in spending.

Ireland’s economic data is well-known now and shocking. Its unemployment is over 12 per cent; it endured a national output loss of 11.3 per cent on its level a year ago; and its inflation rate is minus 3 per cent (that is, a serious deflation) which will further impoverish indebted house owners. Consumption spending has dropped by 20 per cent since the onset of the crisis.

The Irish government has injected €54 billion into the main financial institutions as insolvencies “more than doubled in 2009”. House prices “have fallen by 26.7 per cent since February 2007 and now stand at October 2003 levels”

Ireland was the protype asset price boom fuelled by an out of control banking sector. The Times reports that by 2007 “the country’s houses were the most overvalued in the Western world and construction accounted for one fifth of national output.”

The automatic stabilisers in Ireland have been signficantly responsible for driving the budget deficit towards 12 per cent of GDP so dramatic has the collapse in income generation.

The problem though for Ireland is that it is part of the Euro Monetary System (EMU) and its 12 per cent deficit (as a percentage of GDP) is according to the Maastricht rules out of order irrespective of the state of the economy.

The government already tightened discretionary fiscal policy in April 2009 by withdrawing €3 billion (increasing taxes and cutting spending). Most of the new spending initiatives since the crisis has been to prop up its financial institutions.

In November, the EC gave the Irish government one year extension (to 2014) to get its budget deficit back in line with EMU rules.

So with that sort of outlook why would you entertain a “stinging budget”? Why not follow Japan’s example of fiscal leadership and underwrite aggregate demand to get employment growing.

But in the last week, the Irish government has delivered its “harshest budget in the republic’s history” which is a direct consequence of being in the Euro system.

The problem is that Ireland is an example of a country which moved to a fiat monetary system after the collapse of Bretton Woods in 1971 but, subsequently, decided to impose voluntary constraints on their fiscal capacity and act as if they are still operating in a “gold standard” world. In this case, the constraint is that the Eurozone governments voluntarily conceded their currency monopolies to the European Central Bank without also ceding their fiscal responsibilities.

They also decided, as a consequence, to voluntarily impose the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) which represent a denial of the essential opportunities available to a sovereign nation.

In contrast to countries operating with their own sovereign fiat currencies, such as Japan, Eurozone countries must formally borrow in order to run deficits. Thus the intertemporal government budget constraint applies to Eurozone countries, and will severely limit the capacity of the public sector to fund recovery plans.

Ireland will eventually emerge from the recession when investors resume building capital but it will take much longer than it should as a consequence of its membership in the EMU.

In the meantime, people will become impoverished and a generation of youth will lose access to employment and skill building opportunities and endure life-time disadvantages as a consequence.

From a MMT perspective it is just plain stupid and criminal for governments to indulge their citizens in this way.

Britain continues in the own-goal tradition

Meanwhile, the Irish probably are not better off fleeing to Britain. This article in the Guardian – If I wasn’t so polite, I’d have manned the barricades – summed up a lot of what people must be thinking.

In one section it says:

Meanwhile, directors of the Royal Bank of Scotland, having helped bring the economy to its knees, effectively attempted to hold the country to ransom: if you don’t allow us to continue paying obscene bonuses to our star players, then we shall all resign, they said. They even tried to admonish us for having the cheek to ask for rigour and discipline in their bonus structures.

How can we compete with the galacticos of world banking, they whined, if you don’t allow us to pay them properly? They were asking us to believe that there is some enchanted golden mean in global finance, the knowledge of which is only granted to a chosen few mystics and necromancers. They alone have the power to heal our broken economies and we, the idiot punters, would do well not to interfere.

Meanwhile The Times reports that millions are facing pay freezes or cuts in 2010 as the economy shows no signs of coming out of recession – “Up to two-thirds of companies in the private sector plan to freeze or cut pay next year – a substantial increase compared with this year”.

So real wages are being cut in the UK by a combination of nominal wage freezes or cuts; higher inflation (very modest) and rising taxes as the British government tries to tell the electorate that it is fiscally responsible.

Where is renewed aggregate demand going to come from when you cut the incomes of those who provide the majority of the spending – the consumers?

The British government has already imposed a wage freeze on its public servants to “save money”. This quote from David Frost, the director-general of the BCC, sums up how stupid governments behave when they either fail to understand their options under a fiat monetary system or refuse to use them for ideological reasons:

We face a tough year ahead – it will be a really long haul. The stark reality is that business finances are still under incredible pressure and they are doing everything they can to keep hold of cash.

Wage freezes and cuts are unpleasant but have ensured unemployment has not risen like it did in previous recessions. So far all the pain seems to be felt in the private sector. There have been no such measures in the public sector.

So in the last recession the Government actually cut public sector employment to “save money”. This time they are just cutting pay which still underminines aggregate demand.

Idiots.

We learned the lesson about trying to systematically cut wages in the Great Depression. Things became worse.

In a time when productivity is rising still (which means living standards can rise in material terms) it would be a denial of any reasonable “contract” with workers to be cutting real wages, however that was engineered.

Sectoral wage cuts (for example, the public sector versus the private sector) or industry-specific cuts alter the relative wage structure (some workers are falling behind compared to the “market”). As alternative opportunities arise the cutting sectors will lose labour in order of skill.

Further, while opportunities are limited, the retained labour force is likely to lose morale which directly impacts on their productivity. There are industry studies which show that absenteeism, increased theft, sabotage are all ways in which a demoralised workforce deal with engineered wage cuts.

Fashion statement

The December 23, 2009 edition of the New York Times carried the story – Banks Bundled Bad Debt, Bet Against It and Won – which catalogues again how the big investment banks (Goldman, Deutsche Bank etc) set themselves up beautifully prior to the crisis to gain no matter what happened.

The NYT reports that:

At Deutsche Bank, the point man on betting against the mortgage market was Greg Lippmann, a trader. Mr. Lippmann made his pitch to select hedge fund clients, arguing they should short the mortgage market. He sometimes distributed a T-shirt that read “I’m Short Your House!!!” in black and red letters.

Deutsche, which declined to comment, at the same time was selling synthetic CDOs to its clients, and those deals created more short-selling opportunities for traders like Mr. Lippmann.

Very tasteful.

… and Goldman continues to enjoy cheap credit from the US government (via the Federal Reserve).

China – just don’t buy their stuff!

Some troubled US residents have started a Economy in Crisis homepage. It is hard to determine the group that is behind it but it has Ron Paul, the conservative Republican on its front page and some other conservative economists writing articles.

Their main issue appears to be that they want to restrict trade to reduce the US “reliance on imports”. They complain that the US economy has allowed foreigners to buy their assets; can no longer manufacturer competitively and therefore requires tariff walls to be reinstated; is allowing foreigners to gain control over US industry; is dependent on the Chinese for credit and budget deficit funding and has outsourced too much of its manufacturing, research and design.

It is also concerned with “the record levels of personal, government, and trade deficits”.

Their economic analysis talks about “out-of-control spending and excessive tax breaks” which have led to “the country being over 10 trillion dollars in the red. In order to finance its operations, the U.S. must borrow money from its economic competitors through the sale of Treasury Bonds”.

They also claim this spending and the “free trade” treaties that the US have entered into have blown the current account out and as “jobs have fled the country, so too has ownership of American corporations”.

So it is a real hotch potch of nationalism, Austrian school economics, mainstream economics and US pride where some of the statements contradict others.

They clearly have no understanding of how the monetary system operates, which I could spend some time analysing but won’t.

But the point I want to make (briefly) is that they are for freedom and democracy and choice – but fail to recognise that the principle developments they are concerned about reflect just that – market choices.

China can only do what the Americans and everyone else it trades with allow them to do. They cannot sell a penny’s worth of output in USD and therefore accumulate the USD which they then use to buy US treasury bonds if the US citizens didn’t buy their stuff.

Last time I checked there were no rules in shops requiring Americans to purchase this stuff. Presumably, people buy imported goods made in China instead of locally-made goods (which are more expensive) because they perceive it is their best interests to do so.

I find these “freedom” campaigns curiously contradictory. They hate government involvement in the economy yet propose complex regulative structures (for example, tariffs) which would increase government control on resource allocation and, not to mention it, force citizens (against their will) to purchase goods and services they reject in an open comparison (on price and whatever other characteristics).

They also provide various estimates of how many foreign companies have bought assets in the US economy. But what about US ownership of foreign assets abroad? Is this group going to force US companies to divest of their foreign holdings?

Some of this reminds me of the scares that pervaded the US in the 1980s when the Japan’s Mitsubishi Estate Co. bought control in 1989 of the Rockefeller Center. Then I recall there were the same sort of screams about foreign ownership taking over. As I recall they went broke and sold back to US interests anyway.

What about US trade surpluses to some countries? Is this group advocating they prevent those from happening?

What about US militarism interfering with other nations? Is this group going to advocate no more foreign incursions by the US? How will the massive US military-industrial complex then survive?

Are they really prepared to say to Americans that they should take a lower standard of living by artificially constraining imports (via tariffs) and give away more of their resources to foreigners (via exports)? Are they not aware that tariffs typically do not protect employment over time anyway?

For the rest of us – that is, non-Americans these gee-up groups that have become very vocal as a result of genuine anguish seem an odd quaint to say the least.

Meanwhile … closer to home

Yes, ABC news today is reporting something we already knew – Australians rack up record debt.

Essentially, as a consequence of the Federal government not reforming the banking system, we are now setting ourselves up for the next crisis, especially if the government does not continue to support aggregate demand.

Stay tuned for more on this issue as time passes.

That is enough for tonight.

You say Japan’s bond market is “loyal”… But how do we know Japan’s central bank simply isn’t just buying gov’t debt and obscuring it, like the ‘Federal’ Reserve is doing? http://www.zerohedge.com/article/sprott-calls-fed-ponzi-scheme-half-trillion-treasury-purchasers-are-unaccounted ?

This ‘hail Mary’ pass on the part of the ‘Federal’ Reserve and US Treasury will ultimately end in tears… It seems to me that the US is headed on a bullet train to ruin. requiring massive financial reforms, and ultimately the formation of a new monetary system.

With regards to some of the suggested fixes I’ve read about there, I fail to see how a government that is providing full employment by dictum can possibly also create price stability, as “make work” programs by government ultimately result in a mis-allocation of resources (governments rarely, if ever, allocate resources as effectively as private individuals). But I could be missing something.

IMO, a free market with a few anti-monopolistic and environmental conservation controls (e.g. one with government preventing large businesses from exceeding the size limits the benefit of economy of scale (insuring competition) and protecting the environment (as businesses happily sacrifice this shared resource for profits) seems the only workable solution.

Dear Dave Narby

Lets separate the value statements from the facts. First, the central bank of Japan has been increasing its purchases of Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) in the last 12 months and it has been also buying a lot of private paper under the misguided view that Quantitative Easing will stimulate demand for credit. So in that sense it is acting like the Federal Reserve in the US.

Second, if you go to the Ministry of Finance and examine the statistics relating to JGBs you will soon learn that even though the BOJ is expanding purchases it still remains that the private market in Japan (banks, private life funds) buy the vast majority of the JGBs issued and have demonstrated an unquenchable thirst for them. – about 80 per cent are placed privately. Some 12 per cent are bought by public pension funds, with the remaining being purchased by the BOJ (about 8 per cent) etc for liquidity management operations. That is not a large percentage at all. Here is an interesting English language paper that will short-cut the statistics search for you.

For US statistics on who buys the public debt you can consult Treasury Financial Bulletins. You might be surprised how little the Federal Reserve actually buys. In June 2009 the Federal Reserve held $US748,064 million of outstanding US public debt securities out of a total of $US11,567,551 outstanding – that is 6.5 per cent. In June 2008, the data tells us that the Federal Reserve held $US473,303 million out of a total of $US9,515,532 – so 5 per cent. So we cannot conclude as you do that the central banks in either country are buying all the government debt. They have to buy some for liquidity management operations and have been buying slightly more than usual in the crisis.

I think terms like full employment by dictum are loaded. Who advocates that? The offer of a job at a fixed wage to anyone who voluntarily desires to work and cannot find work is not an authoritative dictum. It is an offer that you can ignore if you like. My bet is that a lot of people would relish the opportunity to work given the private market has failed to supply enough jobs.

Further, all work is “make work” by definition. But I know you think the “market” adjudicates “value”. So how come the market fails so badly regularly – this crisis is about markets not being able to determine value correctly. The resource mis-allocation that market failure involves is enormous. Do you think it is efficient to leave 10 per cent of your willing labour (and 17 odd per cent if you broaden the definition to underemployed and marginal workers) idle? Not doing anything and living in poverty without the resources to fully participate in the “market” in any meaningful way? If you do then we have a vastly different view of what is efficient. The daily GDP losses alone are huge and outweigh all the measurements of “microeconomic inefficiency” – not to mention the huge personal and social costs of unemployment. I think you are “missing something”.

The Job Guarantee offers a fixed wage to anyone who currently has no “market” bid for their services – that is no market demand. It cannot put upwards pressure on prices as a result. That is the source of its price stability characteristics and I suggest you read more about how that would work.

Anyway, thanks for the diversity of opinion.

best wishes

bill

“… as “make work” programs by government ultimately result in a mis-allocation of resources (governments rarely, if ever, allocate resources as effectively as private individuals). But I could be missing something.”

So the internet was a mis-allocation of resources as compared to private investment in equity bubbles? Or the space program, which accelerated integrated circuit design/manufacturing?

I think what we miss is that government spending is relatively transparent as compared with private investment decision-making. It’s easy to criticize government spending because we see the sausages being made. If we had the same visibility into private decisions to allocate resources, we would have a v.different view.

Has every boss you’ve ever worked for been a genius?

What we lack is proper balance – the private sector is never satisfied if they see significant resources commanded by the public. They are so confident they can do better. Consistently when the public allows that to happen the economy blows up.

I don’t know how you have a free market with a “few” anti-monopolistic controls. The government has to have more power than the monopoly interests for this to function – ergo, big government. Besides, if you are free market oriented, what is wrong with monopolies? History repeatedly proves that a free market + competition results in monopolies. As soon as you start with a foundation of “free-market, but”, you basically have the compromise situation we currently find ourselves in.

What the government cannot do is provide for full employment, price stability and private debt protection. Most governments have chosen price stability and private debt protection. Some of us feel that full employment and price stability is a better choice.

@ pebird

Please forgive me, but I can’t take you seriously. You seem to think using “straw man” arguments somehow advances anyone understanding anything. Please refer to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Straw_man , and refrain from doing this in the future if you want serious people to respond to you. If you are unwilling to do this then please GFY. Also, if you think US government spending is transparent you are a damned fool.

@ Bill

All work is clearly not ‘make work, unless you live in a garden of Eden with a perpetual 85F temperature where you can simply lie underneath a tree waiting for food to fall in your mouth. Somebody has to grow the food, cut the wood, weave the cloth, etc. I’m frankly extremely surprised you would even make such an argument.

Also, we won’t know what the ‘Federal’ Reserve really has on their books until we get an independent audit of them. Forgive me if I am among those that do not trust they have the majority of people’s best interests at heart.

Furthermore… Perhaps I’m simply a dunderhead, but IMO If you want people to read this blog and subsequently pressure their political representatives to adopt your ideas, I’d suggest you simplify your arguments and language so that “your mother could understand what you are talking about”.

Personally I hope you do, as I suspect you have some good ideas which should be adopted. But (at the risk of sounding completely arrogant) if I am unable to easily determine what they are, the average person hasn’t a snowball’s chance in hell.

I’ll stick with you a while longer to see if you do (unless this blog is meant for academics only and was never intended for public consumption, in which case I won’t bother you any more).

Dear Dave Narby

First, please keep the tone civil when responding to other commentators (like pebird) whether you like what they say or not. GFY is not consistent with that.

Second, yes somebody does have to grow a surplus but the point I was making was that too often we segment productive and unproductive work along private (market) and public (non-market) lines which I reject. I have written a lot in the past about the valuable additions to our lives and landscapes coming from public endeavour.

Third, I am not one for conspiracies with respect to data publication. If you understand how the data is collected, processed etc you would have to imagine a massive collaborative plot involving thousands (if not more) people over spans of decades for the data to be false. There are so many checks and balances on public data that it would be hard for “them” to distort it beyond what is. Given how many people and levels of operation would have to be involved and not all pulling in the same direction there would certainly have been a major whistle blowing scandal several times over by now. Further, you can assemble shadow data sets in some ways by understanding the scale of the market and what other players are reporting about themselves.

Fourth, I won’t assume you are a “dunderhead”. But my blog is not an academic exercise. I write many peer-reviewed journal articles and publish academic books to satisfy that “market”. I have tried a lot to simplify the concepts and language. But as someone mentioned to me this morning … if you want to understand medicine, for example, there is a minimum level of terminology and conceptual memory that one has to learn before you can start to engage in a debate about how the human body works.

In that sense, there is always some work to be done building one’s own capacity before entering into a specialist area and seeking to engage. I try to define terms that I introduce and explain how these mechanisms and processes work in as much detail as I can. But the matters being discussed are not transparent and have been rendered confusing by the mainstream media and specialist commentary which provides a misleading and typically erroneous account of how the monetary system operates.

Further, macroeconomics is not exactly an easy discipline to enter. In some sense, it “doesn’t exist”! We are used to being able to relate a concept to something we can isolate. But in macro there is no such thing as a “price level” for example. It is an aggregate of many prices and so one has to get into a particular way of thinking which requires some practice.

Finally, my blog is a body of work rather than a standalone post each day. I have systematically tried to build the conceptual structure in earlier blogs which I then call upon on a daily basis. I cannot keep repeating the whole construction each day to make a simple point. Some of the blogs are “educational” (building concepts) while some are just my daily polemic (applying the concepts). So if you are really interested in engaging with the “billy blog community” (which is now made of a number of excellent commentators) then to some extent you have to put in the effort and work through some of the earlier material. I have corralled some of it under the debriefing category.

Stay with us and see where it takes you.

best wishes

bill

Regarding the zero hedge link posted above (and which is floating around everywhere): Eric Sprott has been a very successful Canadian hedge fund manager who ran into a brick wall during the global financial crisis, hurting himself very badly as a result of his autopilot long commodity trade. He subsequently has become the number one cry baby in Canada about all matters pertaining to government conspiracies everywhere. His number two John Embry is one of the biggest gold bug and related conspiracy theorists in Canada. By contrast, Peter Munk is the Chairman of Barrick Corporation, the big Canadian gold producer. He is a gentleman who does not believe in government data conspiracies on gold or anything else as far as I know. Government data conspiracy theories are a comfortable refuge for those who have a vested interest in them, and who are not inclined to do the basic analysis that explains a non-conspiracy outcome.

Dear Bill – am more and more curious about real-world applications of MMT; contemplating the vision and the potential, away from the machinations in the workshop for just a moment or two. I appreciate the necessity to deal with in-house economic concepts, and respond to current issues: but could I tempt you to write on the potential?

E.g – if a country were to reclaim its sovereign right to spend according to the ‘living quality’ of demand, one could easily imagine that there would be no real impediment (other than technological) to develop a green energy grid; or power transportation in an environmentally friendly way. Likewise meet the ‘living demand’ for health, education, food clothing and shelter, within the natural constraints. Am sure, much could be said about the potential?

When a human being is caught up in a conceptual world (and we all are whether its politics, religion, knowledge, humanities, creativity, idealism or organisation etc.) sometimes its good to flop around outside-of-the-box.

Would delight in seeing MMT roaming freely around on the streets, popping up on TV, regional news media etc. enjoying its freedom and articulated clearly. Not everybody has a computer, nor surfs economic blogs! That would be a treat – something that is actually positive – on television!!! You don’t have a hidden extraverted talent as well do you?

Cheers ….

Dear Bill,

I know you have written a fair bit about China and the “debt” that the US has to it. I just can’t find the relevant posts quickly enough although I did a scan through all past posts.

You have also written that imports are “good” and exports are “bad” although I am using this shorthand “good” and “bad” as I’m not too sure what you actually said.

China has sold so much to the US and has a pile of USD in bonds (I thin it is now something like 2 trillion). I get it that there is from a MMT point of view that this is no problem.

But no doubt the Chinese would like to buy more US products and property such as firms etc, eg maybe they would like to buy Boeing or Coca Cola. it seems to me that the US does have a “debt” to China because it would like to buy much of the US, i.e. the debt in terms of the real economy to the tune of 2 trillion. OK, if its not for sale so too bad but the Chinese might get a little stroppy as with Australia which doesn’t want to sell certain things.

So I guess the point I am trying to make is that maybe imports are not necessarily a “good” thing – at least not in the volume that China has with the US or Australia (although I’m not sure how much “debt” we have with them).

Got any comments on this?

Best wishes

Graham

Dear Dave,

Some points from me. This blog is read by a lot of people working in the financial markets and I wouldn’t be surprised if the proportion is higher than that in academics.

JKH and Bill have given their sound arguments against the “conspiracy theory”. The other reason you may find less empathy to what you have to say is the fact that the readers are convinced that a government with sovereign currency faces no issues as far as selling bonds in the market is concerned. I understand that the report that you have linked questions the ability of the US Treasury to “finance” its spending and according to it, it is argued there that it is hiding some facts so that the world does not know that it is facing a problem. However, as Bill has argued in many posts, if an auction fails, its a loss for the investors than any setback to the government. The government is actually doing a favor by issuing debt since it exchanges one form of IOU (deposits or bank reserves) for a higher yielding one. Now this might be difficult to digest, but check some articles in the blog with an unbiased view – this is *the* place to understand the inner workings of the monetary system, macroeconomics and political economy

Pressure from deficit terrorists can cause serious health troubles:

Japan Finance Minister Fujii Admitted to Hospital

Bill,

You appear to blame the current crisis on “market failure” but to the degree that banks are “creatures of the state” and, as structured, were allowed to deploy “head-I-win, tails-you-lose” strategies on the taxpayer’s dime, shouldn’t we allocate some blame to government failure? How do we determine fact from value in such a muddied institutional environment.

Leo

Dave:

I did not intend to misrepresented your position. With blog comments, one tries to advance understanding as quickly as possible. However imperfectly, this is my intention. I really don’t care if you or serious people want to respond, as long as we can progress understanding. Sorry if I hit a nerve. If we were in a bar, I would be more polite.

I interpreted your position as: government is inherently unable to spend as effectively as private individuals. As such, the employment guarantee cannot work. And, as a side note that a free market with a few adjustments is the only alternative that makes sense.

My point was to understand why people have this belief – I think that the process of coming to spending decisions is more visible with public entities whereas private spending decision making is hidden by design. Because people tend not to like compromise, as people over-value negative effects, the political process appears inherently corrupt (I might actually grant that, but for other reasons).

Also, I challenged you with regard to your assertion that public spending results in a mis-allocation of resources. While I admit that the plural of anecdotes is not data, I think a strong case can be made that public spending (with even imperfect visibility) is at least as effective in resource allocation as private spending. Of course, spending should not be all-public nor all-private, the key is in attaining balance.

As you probably know, the Federal Reserve is not a public institution – the lack of visibility into its activities is due in part to its private character.

Finally – and I admit some emotion here – I am tired of hearing about the “free market”. IMO it is an inconsistent fiction that is used to justify almost any position one wants – it is equivalent to invoking religious belief. I know these are assertions, not arguments. But we are posting blog comments, not publishing academic articles nor members of a debating society.

I am a autodidact – I am not a economist by any means. Modern Monetary Theory is difficult to understand because it turns so many “accepted” concepts upside down. It does take time, but you have to be willing to acknowledge that some closely held beliefs may need rethinking.

For example, on Chinese holding our “debt”. Think of our debt as a big savings account for the Chinese. They are free to spend these as they wish. They did invest in other US assets (Agencies), then got burned along with everyone else. They have purchased international assets (Lenovo), and also been rebuffed in some instances. They have also built up commodity surpluses.

No doubt their Treasuries have been used as collateral for international trade, expanding their own sovereign credit position. The Treasuries are very liquid assets that gives the Chinese global financial flexibility. They aren’t buying as many Treasuries now not because they have lost faith in Treasuries, but their exports are down, so they have less dollars with which to buy them.

I can’t realistically imagine a situation where they would want to or need to dump them all at once. I don’t think it’s as big a problem as we hear in the press, but I am certainly interested in other opinions.

Re: “China can only do what the Americans and everyone else it trades with allow them to do. They cannot sell a penny’s worth of output in USD and therefore accumulate the USD which they then use to buy US treasury bonds if the US citizens didn’t buy their stuff.”

I’m just a layman, not an economist, but it seems to me that this response evades the issue. The drive towards “globalization” has led corporations to seek the lowest costs abroad. Chinese semi-slave labor just can’t be beat. As a result, American industry leaves the US and goes abroad where there is cheaper labor. The same happened to the Mexicans: for a while the factories were there until many moved to China where it was even cheaper to produce. So American’s don’t really have much choice; “everything” is made in China. US productive capacity has been hollowed out. Americans are concered that they are being reduced to a third world country. I think they are right.