I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

An unholy gathering is emerging

I mentioned in yesterday’s blog that there is a growing number of deficit-terrorists out there who are trying to appear reasonable to separate themselves from the more loony Austrian-school fringe. They are appearing reasonable by saying that “now we should have deficits” but soon (unspecified) “we will need surpluses” to “pay back the excesses”. That sort of spurious reasoning. Even some self-styled progressives who want us to think they are both reasonable people and knowledgeable commentators are starting to emerge within this broad camp. But in general their arguments reflect, at best, an ignorance of how the monetary system operates. This unholy gathering will prove to be very damaging to the need for a broader understanding of how these operations and how government fiscal interventions impact.

This crazy crew have been helped along in the last few days by the IMF release of its The State of Public Finances Cross-Country Fiscal Monitor: November 2009 prepared by the fancy sounding “Staff of the Fiscal Affairs Department”. Sounds like a make work program to me and after reading the Report I would urge them to get real jobs – productive ones – perhaps helping the community sector or offering to assist in environmental rehabilitation schemes.

I read two articles following my reading of the IMF report … and well … you know … they all reinforce each other’s misconceptions.

Take this article – Worries about Budget Deficits and Inflation: Let’s Avoid Repeating Our Mistakes which is representative of the genre “let’s not cut back just yet but soon we will have to pay it all back”.

The article appears in the self-styled Maximum Utility blog from Mark Thoma. He has a reasonably high media profile in the US and is a macroeconomist from the University of Oregon and he tells us that “his research focuses on how monetary policy affects the economy”.

That is a good thing to focus one’s research activities on. But it is a wasted life if you don’t actually achieve that aim because you are locked into textbook fantasy worlds.

While professing to provide Maximum utility my reflection is that all a reader will get out of this blog is a minimum and mostly wrongful understanding of the way the monetary system operates, and, hence, the way monetary policy affects the economy.

Thoma’s first proposition that when considering the US fiscal position it is crucial to separate out the TARP-type packages administered by the central bank and the more spending-oriented fiscal packages introduced by the Congress (via the Treasury) is sound.

On the former, Thoma says that the Fed policies have meant that “a very large quantity of excess reserves has accumulated within the banking system” and idle reserves “are not much of a problem”. I don’t know whether the use of the word much was anything more than “folksy American jargon” but the reality is the reserves present no problems.

Thoma then notes that the fears that the reserves are an inflation-outbreak waiting to happen are unfounded as “long as we are still below full employment, then inflation – which is driven by an excess demand for goods and services – is not much of a worry.” I agree.

He entertains the idea that when spending recovers, demand for loans will increase and the massive stockpile of reserves in the banking system will be “looking for something to finance cause excess demand and hence inflation?” and rejects it as an inevitability largely because the central bank is paying interest on reserves at present.

So the interest on overnight reserves can be adjusted “to keep the reserves in the banking system and avoid the inflationary consequences”. We have discussed before the equivalence of issuing debt to drain bank reserves and paying interest on reserves and leaving them sitting in the banking system.

My discomfort at this stage reflects the fact that there should have been mention of the fact that once demand begins to recover there will be increasing numbers of credit-worthy customers lining up at the banks’ doors for loans. So?

The capacity of the banks to meet those loans will not be increased at all because they have a stock-pile of reserves (currently earning interest).

Banks just make loans which create deposits and then chase down the reserves they might need later to satisfy the central bank requirements for prudence. They will not make more or less loans as a result of their reserve positions.

Further, if the credit creation and resulting spending is so robust that it pushes nominal aggregate demand beyond the real capacity of the economy to respond to it (in output) then inflation will result. This is a completely separate matter from the state of commercial bank reserves which the central bank will always ensure are adequate for their purposes.

So the question of bank reserves is a furphy. However, Thoma does suggest they might matter because the reserves will be cheaper forms of credit for banks. But the central bank can (as he understands) control that anyway by adjusting the rate it pays on them or draining them by issuing more debt.

Then we turn to the fiscal aspects of the stimulus and here the wheels fall off. Thoma says that with the tax cuts and government spending that was designed to “simply prevent conditions from being much worse than they already are” (because the package was far too small):

The worry here is that government borrowing will drive up interest rates, that the increase in interest rates will lower private investment (this is called “crowding out”) and that, in turn, will cause economic growth to be lower that it would be otherwise.

Right now, this is not a very realistic worry. When the economy is near full employment, and when there are not bundles of cheap cash available from the excess savings in countries like China, an increase in government borrowing adds to the competition for the available funds. The increased competition for available savings drives up interest rates and crowds out private investment. But when there is an excess of available funds, as there is now (this is the excess reserves described above), and cheap loans available from foreigners (e.g. from China) – more than the demand for funds at the current interest rate (which is essentially zero) – the government can borrow without putting any upward pressure at all on the interest rate …

This is a reiteration of the mainstream macroeconomics textbook causality that is categorically rejected by modern monetary theory (MMT).

It is not even necessarily true that higher interest rates lower private investment in a growing economy. Investment decisions compare cost and benefit and when income is growing (as a result of the stimulus and then private spending recovery) even if interest rates are rising so to will be the expected benefits. The textbooks conduct “other things equal” analysis in a static time frame – so they just superimpose a cost increase without considering the income growth.

But that issue is smaller in seriousness to what follows. The implication is that there is a finite savings pool that is the subject of competition from borrowers – public and private. First, saving grows with income and so we say that “investment brings forth its own saving”, which is a way of saying that the income adjustments that occur when aggregate demand change provide a reconciliation between the planned saving and investment.

Second, where do the funds come from that the government borrows? Answer: $-for-$ from the net spending. The government just borrows its own net financial assets back. If you want to profess to understand how the monetary system operates then you have to start with a basic understanding of how net financial assets denominated in the currency of issue enter the banking system in the first place.

Third, the statement “excess of available funds (this is the excess reserves …)” is just nonsensical for reasons discussed above. Statements like this really give the game away … and tell you that the writer is operating in the money multiplier world of the gold-standard textbook. For more on that you might like to read this blog – Money multiplier and other myths.

The reserve situation will not influence the ability or the willingness of the banks to lend. That has been one of the fallacies that this downturn has so categorically exposed. The UK example is manifest. The BoE keeps increasing reserves in the hope that the banks will start lending but the banks will not lend because there is no credit-worthy borrowers (in their estimation) lining up for the loans. If there was they would lend – huge stockpiles of reserves or not.

Fourth, the central bank sets the interest rate at whatever level it desires.

After claiming that the health care issue in the US will represent a future financial constraint on US fiscal policy (it will not – although it might give the Administration a huge political headache (excuse the pun)), Thoma then gets more confusing. He says:

I don’t want to be misunderstood. It’s important that, once the economy recovers, we do what is necessary to pay for the stimulus package … Doing stabilization policy correctly requires deficit spending in bad times, and then paying for that spending when times are better. We have been very good at running up deficits during the bad times, but not so good at paying the bills when things improve, and that needs to change.

But beginning to pay down the deficit too soon can endanger a recovering economy, and it’s important to be sure that the economy is on solid footing before starting to pay the bills for the stimulus package. The day will come when it’s time to do just that, but we are not there yet. (In fact, given the poor state of the job market, I’d favor even more stimulus presently, particularly programs that directly target jobs).

So this is a deficit-dove with good intentions talking. The last sentence in brackets is impeccable – with 17.2 per cent of willing US labour resources currently broadly underutilised – there should be further stimulus and it should be in the form of direct public job creation – like a Job Guarantee

But what comes before that is unsound and gives the game away.

First, a household has to “pay for” any past spending above income. The only way a revenue-constrained household can spend above its income is if it borrows, runs down assets (including saving) or sells things for revenue. Each of these “financing” sources involves a form of “pay back”.

But there is no applicability in using this logic for a sovereign government which issues the currency. Governments do not pay down deficits. Deficits are flows – daily occurrences – yesterday’s deficit is gone and won’t be coming back.

So what he is talking about is the debt, which is the stock accumulation of the flows, given the voluntary and stupid constraints the US government places on itself when it net spends.

So why doesn’t he just say that straight rather than use language like “time to pay the bills” (which evokes household comparisons)? Rhetorical question!

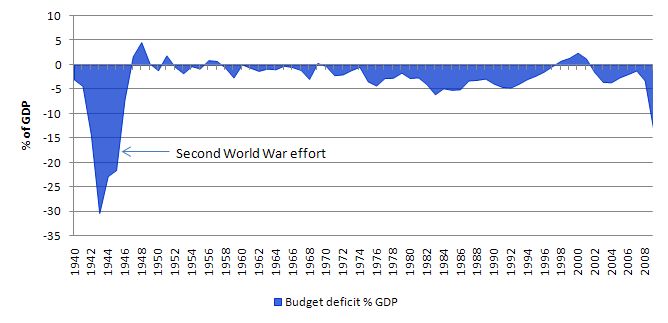

You have seen the next graph before. It shows US Government budget position as a percentage of GDP (deficits are below the zero line) from 1940 to 2009 (data from US Bureau of Economic Analysis). So a large rise in the ratio during the Second World War then consistent deficits ever since except for a few misguided times when the government tried to run surpluses only to find they ran against leakages from the expenditure system that forced them back into deficit (via income adjustments and the automatic stabilisers).

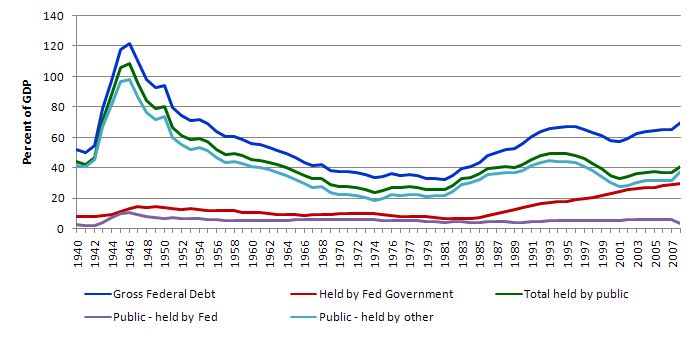

The next graph shows the evolution of US federal debt from 1940 to 2008 split into components (data from US Office of Management and Budget). So the blue line is total (gross) federal debt, the green line is the total federal debt held by the public (noting they count the holds of the Federal reserve, the central bank, as public – purple line), the red line is that held by Federal government accounts, and the indigo line is the non-fed public holdings (public here means private or non-government).

The break-up is interesting in itself and the OMB provides further details. If I was a debt phobe I might spend a lot more time wondering about it but as I am not the essential point I will make here is that with the almost continual deficits that the US government was running over the time span shown, the Debt/GDP hardly exploded and so arguments that imply that the government will have to run surpluses to “pay for the party” are fallacious.

So while national government’s clearly pay the debt they issue at an appropriate time as per the “contract” this in no way reduces their capacity to keep running deficits. No-one is saying that the central bank interest payments on overnight reserves will limit its ability to provide reserves in the future. It would be a nonsense to say that.

Well why would you suggest that the simple crediting of a bank account at some point in the future – with a corresponding ledger entry – bond repayment XXXXX – would financially hamper the capacity of the federal government to spend at that time? It clearly will not. So what does the notion of having to “pay for the deficits” mean? Answer: nothing. For more on that you might like to read this blog – I guess they didn’t want to win the wars.

Conclusion: pity the students at the University of Oregon who have to learn this stuff.

After that I sought relaxation by reading the latest Martin Wolf contribution in the November 23 edition of the Financial Times – Give us fiscal austerity, but not quite yet.

I knew it would make me laugh and they say laughing is good for you and relaxes you. I wasn’t wrong.

Here is a teaser. Wolf said:

So what is the problem? It is that people may lose confidence that the governments will ultimately bring deficits under control. There are at least two reasons for such doubt. First, wars have a natural ending, while deficits in peacetime do not. Second, cutting deficits at the end of wars is easy, while cutting peacetime deficits is hard: every pound or dollar comes with a lobby group attached.

You get the drift. Deficits cut themselves in peace-time when the economy grows again. A significant portion of the deficits that have arisen around the world in response to the crisis has been by the automatic stabilisers. This involves no political pain – it will just happen because more people are working and enjoying life again.

What remains of the budget deficits as the economies approach full employment (if they are allowed to by their governments) may actually match the leakages arising from the external and domestic private sector. Nothing needs to be cut out of net public spending if that is the case.

If there is excess nominal demand growth at that point then the government has options. Increase taxes and/or cut spending. But their economies will be bouyant and incomes will be high and at that point the political decisions are much less likely to cause individual damage or widespread political fallout.

Wolf fails to mention the automatic stabilisers anywhere in his article even though they were so significant in accounting for the increasing deficits. Why not?

Well for the same reason Thoma uses misleading household-type language “paying back the bills”. It forces the reader into a particular state of mind.

If the average reader knew that say 80 per cent of the deficits will be wiped away once the economy gets back onto trend growth because unemployment falls and people have higher incomes and more enjoyable lives then there would be no story for the conservatives to write.

Wolf concluded this article in this way:

So what should be done? I agree fully with the remark by Dominique Strauss-Kahn, managing director of the IMF, in London this week that “it is still too early for a general exit” from accommodative policies. That applies also to the UK and US. What is needed, instead, are credible fiscal institutions and a road map for tightening that will be implemented, automatically, as and when (but only as and when) the private sector’s spending recovers. Among the things that should be done right now is to put prospective entitlement spending – on public sector pensions, for example – on a sustainable path. It is, in short, about putting in place a credible long-term tightening that responds to recovery automatically.

Yet we also cannot escape from an “inconvenient truth”. Neither the UK nor the US is quite as wealthy as it once believed. There are losses to be shared, much of which will fall on public spending, taxation, or both. Once it becomes evident that neither of these countries can rise to the challenge, fiscal crises are inevitable. It would only be a question of when.

Well there is a credible “road map” that “will be implemented, automatically” which will wipe many percentage points of the deficit to GDP ratios that are presently being witnessed. They are the automatic stabilisers discussed above.

Anyone who knows anything about macroeconomics knows about them and knows how they work.

Anything more than that doesn’t make sense unless Wolf is claiming that he could perfectly forecast the desired non-government saving intentions in the coming years.

My bet is that households in general will not return to their credit-bingeing past and will continue to consolidate their balance sheet by saving. I cannot foresee a return to aggregate private dis-saving.

So for all countries with current account deficits, that means there will be deficits required to keep growth going and to allow the private sector to continue this process of consolidation.

Wolf seems to be in denial of that prospect and the accounting realities that arise as a consequence. Or if he knows about them he prefers not to tell the reader.

Why? Because he just wants to get to his punch line as misleadingly and/or wrongfully as he can – that way he can assert that a fiscal crisis is inevitable.

Conclusion: hack journalism.

But if you really want a laugh read this little extract, which is one paragraph of many along the same theme, from what appears to be a rival to wikipedia – wait for it – conservapedia

In the 1990s leftists in Australia demanded strict gun control based on isolated violence that was sensationalized in the media. Predictably, the rate of assaults in Australia increased with the stricter gun control, and the politics of the country moved to the Left in greater reliance on government protection.

The isolated violence was the slaughter of 35 people in 1996 (another 19 were were seriously injured) in Tasmania. Australians have never been able to bear guns. Further, the legislation was introduced by the previous conservative government which went as far right in the political spectrum as any government had ever gone over here.

That’s enough for today.

Thanks Mr Mitchell

Your blog is becoming daily reading for me ever since I found it a couple weeks ago. This MMT is powerful stuff.

Would you be amenable to doing an online Q&A or a blog debate with someone from the “debtaphobe” side on one of the more popular US econ blogs like Naked Capitalism, Economist’s View (Mr Thoma’s blog) or even Angry Bear? I think the proponents of MMT have to aggressively seek opportunities to directly confront the toxic misrepresentation of our financial system. Its toxic because the ideas put out by the debtaphobes lodge in your brain and slowly work towards killing all ability to think coherently about the true state of our financial system.

I’ve asked Yves Smith (Naked Capitalism) If she would mediate such a discussion and I will ask Mark Thoma as well.

If contacted by them please lend your valuable voice to the discussion. People need to hear it.

Civilizations future is at stake!………………………………………………………………………. well that may be a tad overstated, but only a tad.

During a little historical digging, what I find interesting are the similarities of policies and politics between the Great Depression and current crisis.

During the GD, bank reserves also increased significantly – in Jan 1934, total reserves were $2.8 billion of which $900 were excess. By 1935 total reserves were $5.8 billion of which $2.1 were excess. Still, lending did not increase (of course). But the banks were “worried” about the inflationary pressures of the reserves representing a source of multiplying the money supply, and pressured the government to restrain spending. Until WWII.

What the recovery due to WWII represents is the POLITICAL alignment needed to finally spend the appropriate amount to create sufficient demand. This also demonstrates the degree of spending necessary to generate employment and the weakness of the current stimulus.

If there are no “lobby groups” around at the end of wars, then Wolf never took the time to look at the history of the US aerospace industry, the munitions industry, the “security” industry and other assorted “private” industries that would be forced to declare bankruptcy if government spending were eliminated.

The economic hackery is bad enough – when easily refuted assertions are continually spewed by the mainstream, you realize the Orwellian character of the media.

Sometimes I think economists like Thoma (and Krugman) know more than what they are saying, but need to keep their jobs and positions, so they dance around the problem. No one wants to be Galileo – it doesn’t matter if you are correct if you are placed under house arrest.

With regard to we in US and our “folksy jargon”, I had to lookup “furphy” and now I am one piece of international jargon smarter.

Not to mention the TARP spending on financial assets shouldn’t be counted in federal deficit discussions that are about aggregate demand issues.

So the deficit spending that’s relevant to agg demand is actually quite a bit lower than the chart shows.

Bill –

About the automatic stabilizers: isn’t it true that in a country with a progressive (or, for that matter, any sort of) income tax, any money spent by the government must, as a matter of mathematics, return to it? If I get paid to build a ship for the governement, it immediately takes back about 30% at the end of the year. With what I have left, I go out to a restaurant – and the money I pay for my meal is taxed. The restaurateur buys a car – taxed. etc. etc.

THe only variable is long it takes for the money to flow back to the treasury. When money velocity is low, the flow can slow down. When it’s faster it speeds up. You can change the tax rate to speed it up or slow it down as well. But the debt will always pay itself back eventually, no matter what the government does.

I only point this out because it might be a better way to educate debtphobes about the utter ridiculousness of talk about “bankruptcy” – fiat money tends to make people’s head’s spin, but everyone understands taxes.

From what I can see, the growth fuel for the neo-liberal era has been the relentless expansion of the the private sector debt-to-income ratio. In many places (Australia being one possible exception for the time being at least) the private sector appears to be “maxxed out”. Perhaps despite our fears and despite the neo-liberal attempts to return to “business as normal”, this is no longer possible by the same means that got us here.

If high unemployment and sluggish growth become an entrenched feature and things appear to be stuck permanently in the doldrums, only then will people sart asking en masse “is there a better alternative to this?”

It is a law of nature that the sun rises and then sets on everything and the ugly system of neo-liberalism is no exception. I only hope that it comes sooner rather than later.

Bill,

Can you clear something up for me? How does a bank ‘lend’ its reserves?

When a loan is created, presumably the loaning bank credits the borrowers bank reserve account from its own? So the lending bank loses reserves and the borrowers bank gains reserves. So no net change in reserves, they just move about.

I guess the inflationists worry is that this can happen any number of times and hence be very inflationary. But as we know banks are constrained by their capital ratios not their reserve account balances.

So is there any milage at all in claiming that the inflation concern is related to velocity of money (the circling round and round of a given aggregate quantity of reserves) rather than an increase in the velocity of money.

Say the CBs of the US, UK, Japan, sweden decide to charge interest on reserves. Does that quantitiy of reserves in the system then matter quite a bit even though they can’t really affect the size of the money stock?

” fiat money tends to make people’s head’s spin”

Exactly jimbo. I thought that if an old school janitor could grasp the basic concepts of it, then that school janitor should be able to explain it to anyone. But many people seem to have difficulty getting their head around the idea. Abstract concepts can be awkward.

following on from the above, what is the MMT answer to what happens if I borrow from bank A, which credits my deposit account at bank B, and bank B’s reserve account with the same, and then I use that loan to buy shares in my bank, bank B?

presumably bank B capital ratio improves facilitating new lending – but what happens to the reserves associated with my deposit at bank B?

Bill:

This is Mark’s reply on his blog for Greg’s request for a debate with you.

Dear Vinodh

A suitably religious reply. Some work experience in a bank, followed by some more work experience in the central bank would help.

I also said that you could not consider what happens to investment in a growing economy by only focusing on the cost of funds. There are two sides to the investment equation cost and benefit. So if he chooses to misrepresent me for his own purposes more the shame and speaks to motive.

Best wishes

bill

Bill,

I’m not clear whether you think that a rise in the interest rate paid on Treasurys represents a good, bad, or neutral event under conditions where Federal debt is 40%+ of GDP and expected to go higher (average projections range from 60% to 80%). Here in the U.S. some of us have noted that the neo-liberal models’ straight line predictions that higher Treasury issuance must produce higher Treasury interest rates is in shambles. Global bond markets (and Treasuries operate in such a market) are complex animals and there are too many highly dynamic factors that determine the market rate at any given time for such a simplistic formula. I know that MTM in theory asserts that no gov’t debt at all is actually necessary, but in the current world such debt exists and interest must be paid on it. Setting aside for the moment all the hyped anxiety about the “economy-destroying effect of deficits”, there remains the question of a high national debt that must be rolled over at some future time when the market is demanding higher interest rates to continue to purchase that debt. How high might those rates go? Well, I remember Treasuries looking for buyers at 15% interest 30 years ago – an example of the reasonably possible. Given there isn’t going to be a default on such debt, and given that the kind of surpluses it would take to keep the debt at level it was thirty years ago (and how devastating such surpluses would be on the economy), it would seem like potential rises in Treasury rates could create a very, very big crisis in a very, very short period of time. What do you think?

scepticus, Bill,

If I may interject here for a moment, if you have two banks, Bank A and Bank B, Bank A issues to a borrower a

loan of say €100,000 amount. The borrower gives a cheque for the above €100,000 amount to a customer of Bank A

who is not a borrower. Both sides of Bank A’s balance sheet rise by €100,000. It’s balance at the central bank

is unchanged, hence the money supply has increased by €100,000.

If bank A repeats the above exercise say 5 times, this raises it’s balance sheet 5 times, but there is no

change of it’s balance at the central bank.

Now if Bank A issues to a borrower a loan say of €200,000. The borrower gives a cheque to a customer of

Bank B who is not a borrower. Bank B clears the cheque, and as a result €200,000 will be debited to Bank As’

account at the central bank, and be credited to Bank Bs’ account at the central bank.

The assets of Bank A have changed, a loan to a customer having gone up, and it’s balance at the central bank

has shrunk by the same amount, but its balance sheet total remains the same, even though it has increased the

money supply by its lending. Bank B has €200,000 too much on its account at the central bank, so it lends €200,000

to Bank A because it will usually get a higher rate of interest in the interbank market than it will

get from the central bank.

If Bank A cannot get the balance from Bank B, the central bank will lend it the difference or it will buy an

asset from Bank A. Bill, is this not dissimilar to quantitive easing?

The problem with Mark and the rest of them is that they don’t won’t to be wrong because their whole intellectual

edifice comes crashing down. Imagine, you spent you’re whole career teaching and you reached that stage in life

and you realised it was all nonsense. The only thing they leave behind is misery.

Bill, you should bypass them. Have you ever played that SimCity game http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SimCity.

***********

Objective

The objective of SimCity, as the name of the game suggests, is to build and design a city, without specific goals

to achieve (except in the scenarios, see below). The player can mark land as being zoned as commercial, industrial,

or residential, add buildings, change the tax rate, build a power grid, build transportation systems and many

other actions, in order to enhance the city.

Also, the player may face disasters including: flooding, tornadoes, fires (often from air disasters or even

shipwrecks), earthquakes and attacks by monsters. In addition, monsters and tornadoes can trigger train crashes

by running into passing trains. Later disasters in the game’s sequels included lightning strikes, volcanoes,

meteors and attack by extraterrestrial craft.

In the SNES version and later, one can also build rewards when they are given to them, such as a mayor’s mansion,

casino, etc.

***********

I played it in Secondary School, maybe you’re version can be called Real Life®. The Objective of which is to create

full employment, with all the above disasters popping up such as those neo-liberals, full scale recessions/depressions and how to mitigate against them with the inbuilt automatic stabilisers. It will be sent to all secondary schools, so the time they leave they will know how the real monetary system works. Maybe you can have a help section when the students can’t get started such as a library with various books that will encourage the students to research how to get started, such as the real reason for tax. Maybe have a competition between different schools linked over the interent and have a reward for the first school to create full employment.

By the way, this is one of the best blogs I’ve come across. And I appreciate the amount of work you put into it.

Regards,

Barry

Dear Barry

I will respond to other comments in detail when I have a little more time (perhaps this weekend). But I thought about building a MMT world on Second Life but that was not possible because they will only allow you to use their currency.

So I have this plan to start another virtual world … with a fiat currency etc … I haven’t the time to do all the programming myself and would love to work with some others on an open-source basis to build this new world and see where it might take us.

So an open invitiation to anyone to contact me if you can help.

I am all the hosting, network capacity – just not enough time to write all the code.

best wishes

bill

Wow. I’m flabbergasted at Mark Thoma’s response. I’ve seen reactions like that before on the part of people with a huge vested interest in the status quo when they are asked to address something that they don’t fully understand and feel may be threatening. It seems pretty clear that a lot of economists have never thought through the accounting upon which their macro models involving government (Treasury and CB) rests. Rejecting a challenge on the basis of ideological authority is pretty telling in a subject that holds itself out as a science. Makes sense of another economist’s statement to the effect that he’s open to debate now only because he’s over the hill and has no turf to defend.

Posted this to Nick Rowe’s site regarding his and Thoma’s disagreement with Bill on interest rates and investment spending:

Regarding the discussion on Thoma’s site about real interest rates, the people who actually study how indivdual real world firms make investment decisions in the field of corporate finance will tell you that decisions are based upon criteria such as NPV, IRR, or MIRR. For those measures, there are two drivers: anticipated free cash flows and the discount rate. You can lower the discount rate (real, nominal, or whatever . . . though most analyses suggest the nominal discount rate is more important, albeit with an assumed change in prices paid and sold factored in to the cash flows), but if anticipated cash flows have fallen, the criteria can still be saying don’t invest. This tends to be the result in a recession, the opposite (rising rates and rising cash flows, but the criteria on balance saying to do the investment) tends to be the case in an expansion. This was Bill’s point (which is, again, completely consistent with research in corporate finance) that Thoma and Nick are taking issue with for some reason. Any basic senstitivity analysis will usually show you that the criteria are much more sensitive to a change in the anticipated cash flows than they are to a change in the discount rate. Further, if we add in growing application of options theory to investment decisions, then the discount rate becomes still less important relative to analysis of cash flows (anticipated and now volatility thereof). Further further, the insistence on a downward sloping IS is puzzling . . . if you raise interest rates to 20% in Japan (which would also be a significant increase in the real rate there), given the size of the national debt, it would be hard to say you don’t on balance raise spending there as interest payments would generate a considerable increase in income (which then the spnending might stimulate investment . . . might).

Another thing to add to this is that it’s well known that risk premia on required returns to corporate debt and equity are countercyclical, lending more support to Bill’s point, so even the discount rate used to determine NPV, IRR, MIRR, and so forth won’t necessarily follow the cbs target rate. Indeed, it’s quite strange that neoclassicals think the overnight interest rate target (real or nominal) can have such direct effect on investment spending.

It seems to me that a raising of the CB target to 20% in Japan would bankrupt the banks and plunge the economy deeper into a deflationary depression. Nominal yields would be pushed down across the board — any additional coupon income from the government would be offset by a general decrease in broad money relative to base money and a corresponding decrease in the total number of purchases.

As every income stream from a bond sale is purchased at fair market value, I’m curious as to why you think that if I send $100 to the government, and then have that money dribbled back to me over time, that this will result in additional transactions occurring — are you saying that investors are systematically mis-pricing those yields and would not be able to get the same risk-adjusted return if they invested that money elsewhere?

I certainly believe that expectations of returns often fail, but I don’t see why they should be biased towards failing in one direction over another. Or am I misinterpreting the comment?

The point is that interest on the national debt would skyrocket, and virtually all of that goes to domestics, and most of the national debt is in shorter maturities (I assume . . . standard practice for the most part, and I withdraw the suggestion if it’s not the case). Yes, anyone holding long-terms T’s would see a capital loss, and a big one at that. So you’d have to weigh the balance of those effects, for sure (and note that the capital loss would be one-time, whereas the interest on a debt of over 150% would continue to climb as a percent of GDP). But note that the basic intertemporal government budget constraint ASSUMES that rising debt service on the national debt is at some point inflationary, even hyperinflationary, so there is thereby an implicit assumption that the effect of interest on the national debt going to savers on balance has a much greater effect on aggregate demand than do the other negative effects. So, if you’re right, then most concerns about rising interest on the national debt are misplaced, as they can’t outweigh the negative effects of the rising rates on the banking system. Either way there’s an inconsistency at the heart of the neoclassical interpretation of either the IS curve or the intertermporal budget constraint.

Scepticus @ Friday, November 27, 2009 at 5:19

You borrow from bank A.

A writes you a cheque.

You deposit the cheque at your bank B.

Bank A transfers reserves to your bank B through the interbank reserve clearings.

You buy stock in your bank B.

If it’s an issue of new stock, B debits your deposit account and sends you a stock certificate (or you get electronic credit for the shares).

B now has a book entry for new paid in equity on the right hand side of its balance sheet, instead of your deposit.

With respect to reserves, your bank B originally received reserves from A in the interbank clearing, after you borrowed from A and deposited the proceeds (e.g. cheque drawn on A) with B. Other things equal, bank B is in a surplus reserve position due to your original transfer of funds to it. In addition to bolstering its equity capital position, bank B by issuing new shares will expect to attract reserves from the rest of the banking system, although it’s unlikely the size of the share issue will be matched in full by an equivalent transfer of reserves. That’s because some of the buyers of the new share issue will be existing depositor with B. Their transactions will be reflected as an effective swap of their existing deposits for equity shares – the same as the second half of your transaction. In a relatively concentrated banking system with big players like Australia’s (I think), major banks doing large share issues will actually do an ex ante estimate of the likely net reserve effect of a new share issue based on netting out their own pro rata share of deposits in the system. That assists with short term cash and liquidity management.

As to what happens next to the net reserves transferred, they will soon get absorbed into the ongoing asset liability management of the recipient bank, although there will be a noticeable “bump” in its reserves when the share issue settles on day 1. That’s easy to take care of. The bank will just deploy those reserves by acquiring short term low risk money market assets such as treasury bills, which will reverse the reserve inflow that came in from the share issue. The interbank clearing will tend to “push” the reserve distribution back to the other banks. From that starting point, the bank is in a position to expand its acquisition of risk assets over time based on its strengthened equity capital position. That’s usually done over a longer term horizon, unless the share issue was done to offset some large strategic acquisition on a one off basis or to make up for an unexpected prior loss in equity capital.

This shows the difference between liquidity and capital. The strategic effect of the share issue has been to increase the bank’s equity capital position. That’s what allows it to take on more risk in the future – e.g. taking on more credit risk by increasing its loan book. In terms of liquidity, it has for the time being improved its position, in the sense that it has additional resources to offset a future reserve outflow that might be associated with future loan book expansion (e.g. by selling those just acquired liquid assets). But the longer the time horizon for new capital deployment, the more the liquidity effect of the share issue gets rolled into the day to day operational management of the bank.

This is all consistent with MMT. Banks need appropriate capital levels to lend. They don’t need existing reserves to lend. But they want to be able to square their reserve positions operationally when they do lend or when they engage in any transaction. They do this in the normal course by asset liability adjustments that offset any reserve outflow due to such transactions. MMT says that the central bank will always make such reserves available to the system as a whole, one way or another, even if it’s through discount window lending. An individual bank that lends just finds those reserves as necessary in order to square its account with the central bank. It can find them by calling on its own excess reserves if it has them, selling/maturing short term liquid assets if it has them, raising new liabilities in the market if it needs to, or borrowing from the central bank. Banks are not reserve constrained in risk lending, because one or more of the first three options are normally available and the final option is always available.

Hi Scott,

Absolutely there are many inconsistencies in the neo-classical model; I was pointing out that interest on the debt would not skyrocket, but would decrease as a result of a central bank target hike. I also agree that Treasury debt sales will not increase yields long term, but of course the financial markets are not perfectly liquid.

It pays to look at the channel by which a CB target rate hike affects investor yields. Clearly the Fed can force rates in the interbank market to rise, but how does this transfer to yields on investor rates?

Define a “financial market” channel: FedFunds rate — 3 month commercial paper — 3 month yields.

And then a “real economy credit channel”: FedFunds rate — debt service costs — changes to aggregate demand — changes to perception of potential returns.

The first leg of the financial channel really operates via liquidity squeeze in the commercial paper markets, as you have a large amount of debt that must be rolled over, and so is more price insensitive. In a perfectly liquid world in which both borrowers and creditors would be instantly and costlessly adjust their capital structure, FedFunds rate hikes would have no effect via this channel, and even now there are leakage in which a FedFunds hike of 500 basis points can result in a 3 month commercial paper hike of only 300 basis points. At other times, FedFunds is rising while commercial paper rates are falling, etc.

The second arrow in the financial channel is undermined by the real economy channel, as banks will suffer defaults during a rate hike and their risk premium will increase vis-a-vis government debt. This graph of Volcker’s rate hikes may be helpful — you can see how FedFunds hikes caused 3 month rates to increase up to a point, but when the economy (and banks) began to fail, the 3 month yields started to fall. At that point the CB target rate better chase the 3 month rate down, otherwise you will lose all the banks. Volcker’s hikes caused enough defaults to wipe out all the bank capital of the NYC money center banks three times over and plunged the economy into a deep recession. It certainly did not increase incomes, either of banks or of investors. Nobody got increased incomes during that period.

In think in the case of a massive rate hike in Japan, because the private sector is so much more indebted than the U.S. was in 1980, you would be lucky to get even 1 month of rising short term rates before the nation would be plunged into an extreme deflationary depression and government yields would quickly fall. I don’t think they would ever rise above a few percent even for a few weeks, regardless of what you set the CB target to, because the private sector in Japan cannot afford to pay high rates. In general, it is a fallacy to assume that the CB target rate corresponds to net interest income received by the private sector, and the fetishizing of the central bank target rate — which is not even a “real” interest rate — undermines economic understanding. The CB target is just one of many administrative costs that the government imposes on banks, and the interaction between this cost and investor returns — even short term returns — is complex.

It is also a fallacy to assume that net interest income is additive to total returns on capital, or that it is deflationary to “deprive” investors of coupon income by having the government buy their claims at fair market value.

Dear Tom

I was not surprised by Mark’s response. Avoiding engagement with alternative (rival) theoretical viewpoints and even personally ridiculing there proponents is one of the cruder ways that dominant paradigms maintain their sense of authority. I doubt that Mark (or any of them) have taken the time to read any modern monetary theory whereas all of the MMT characters have a deep and technical knowledge of mainstream economics.

I think that is a telling asymmetry and is always present when a paradigm is degenerating (in the meaning of Kuhn and Lakatos) and cannot explain the world before our eyes.

Joan Robinson commented that mainstream economics is a branch of theology – it being all a matter of faith.

Statements like “of-course there is a money multiplier” are just expressions of that faith (“of-course there is a god”). However, if the economists who asserted that so boldly went into a bank and studied exactly how they operate they would quickly understand the the mechanisms specified in their textbooks (“bibles”) were not adequate representations of those operations.

The typical reaction is then to deny the observations as being contrary to theory. I have heard that over and over again in my career.

best wishes

bill

JKH thanks vry much for that explaination.

it seems to me that the provision of additional reserves to the commercial banking system provides the opportunity for some fraction of those reserves to be used for new bank equity capitalisation, and opportunity that would not have been available (at least in the same degree) prior to the creation of new reserves by the central bank.

Is it your opinion that this one of the outcomes the central bank is aiming for in the creation of excess reserves in the current situation.

Also I am not clear what the potential effect on velocity is of the excess reserves, leaving aside the bank capitalisation issue.

Bill,

I think you slander the good name of theologians by comparing them to economists. If they are doing theology, it is bad theology. Thomas Aquinas would shred these guys to ribbons (and in fact, he was a better economist…)

scepticus,

Two perspectives on your question:

First, the operational view: As I described in my previous comment, what happens generally in a new equity issue is that bank deposit liabilities are exchanged for new bank equity – that’s the result on a system wide basis. The amount of new reserves that a bank attracts with a new equity issue depends on the degree to which the new equity buyers pay for their stock by drawing down deposits at banks other than the equity issuing bank. But there is no constraint in terms of the effect of the level of existing bank reserves on the ability for a bank to issue equity or for potential buyers to purchase it.

Second, the strategic view: The US monetary system is currently in a position of what I describe as “structural excess reserves”. These are the vast quantities of excess reserves that the Fed has poured into the system as a result of the money created by its own extraordinary credit expansion during the credit crisis. You can think of this excess reserve position as a massive risk transformation. Essentially, banks and non-banks that previously supplied credit to the private sector are instead now depositing their money with the Fed – directly in the case of banks, and indirectly in the case of non-banks that have put their money on deposit with the banks. All of this money on deposit (non-banks with the banks; banks with the Fed) has essentially been created by the Fed through their own asset initiatives. The result, other things equal, is that both the banks and the non-banks have dialled down their risk levels relative to what they might have been otherwise. The banks in particular now have about $ 1 trillion in risk free reserves place with the Fed. This means that the banks have a lower risk weighted asset profile than would otherwise be the case. And their capital position is better as a result, again other things equal. However, other things equal is a treacherous slope. We know that other things aren’t equal and that the banks continue to face capital pressures due to the severity of the recession and credit losses and remaining credit exposure. Nevertheless, the Fed’s intervention has alleviated some of the risk burden on the banking system. So that means that there is some benefit flowing from the excess reserve position in terms of the marginal effect on the risk weighted asset profile of the banking system. And that means that there is a marginal benefit in terms of the capital adequacy of the banks and perhaps their ability to attract new capital.

On velocity, I tend to steer clear of that sort of analysis. I don’t think it’s particularly useful. Velocity is a plug item, depending on what you choose as your flow numerator and your money stock denominator. There are various choices in either case. One thing to watch out for is that the erroneous “multiplier” argument in a sense invokes a sort of velocity explanation for bank reserves. I’d stay away from that too.

Yes, it’s such a shame that so many reports are reinforcing Keynes and the people whom you call “deficit terrorists”. If only some signs would appear that proving how right you are and how wrong they are. I guess we’ll have to keep waiting.

Dear bill,

In your reply to Vinodh, you speak about “two sides to the investment equation: cost and benefit”. Thus, the precedent of your implied prediction is a logical AND. You only have to be wrong about one of them in order for your logic to fail. But it is understandable, therefore, why you are complaining about the inconvenient facts in those reports.