With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

Japan’s municipalities disappearing as population shrinks

I have just finished reading a report from the Population Strategy Council (PSC) of Japan – 令和6年・地方自治体「持続可能性」分析レポート (2024 Local government “sustainability” analysis report) – that was released last week April 24, 2024). The study found that around 40 per cent of the towns (municipalities) in Japan will likely disappear because their populations are in rapid decline as a result of extremely low birth rates. The shrinking Japanese population and the way in which local government areas are being challenged by major population outflows (to Tokyo for example) combined with very low birth rates makes for a great case study for research. There are so many issues that arise and many of which challenge the mainstream economics narrative concerning fiscal and monetary impacts of increasing dependency ratios on government solvency. From my perspective, Japan provides us with a good example of how degrowth, if managed correctly can be achieved with low adjustment costs. The situation will certainly keep me interested for the years to come.

The PSC is a private sector research body and defined the risk of disappearing as being if the population of women aged between 20 and 39 years would fall by 50 per cent between 2020 and 2050.

The work was a decade-update on a study released by the Japan Policy Council in 2014.

That organisation no longer exists and its work has been replaced by the PSC.

In 2014, the JPC considered 896 local municipalities would disappear.

The latest study concluded that out of 1,729 local areas examined (translated from original):

… there are 744 local governments where the rate of decline in the young female population, assuming migration, will be 50% or more between 2020 and 2050 (local governments likely to disappear). This is a slight improvement compared to 896 local governments in 2014 … Of these, if we exclude municipalities in Fukushima Prefecture, which were not included in the previous survey, the total number is 711. This time, 239 local governments escaped the status of local governments at risk of extinction. Of the 744 local governments, 99 (including 33 local governments in Fukushima Prefecture) were newly classified as local governments, which are still at risk of extinction both last time and this time, but the decline rate of young female population has improved.

They cautioned though that while there had been some improvement, the birth rate in Japan has not changed much – falling slightly.

The improvement they identified has come from the fact that there are now more foreigners living and working in Japan that there were in 2014.

The research is based on projections provided by the – National Institute of Population and Social Security Research – which is a government body under the oversight of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and functions “to collect accurate and detailed data regarding the current state of the Japanese population and its fertility rate and to produce highly accurate estimations of future trends based on careful scientific analyses perforated on that data.”

Their most recent projections from 2021 to 2070 – Population Projections for Japan (2021-2070): Summary of Results – also provided long-range projections from 2071 to 2120.

They estimate that in June 2023, the “number of foreign residents in Japan reached an all-time high of 3.22 million … and comprehensive measures for acceptance and coexistence of foreign nationals are being implemented.”

So the notion that Japan is “closed to foreigners” is “undergoing major changes”.

The PSC study also offered ideas on what measures local area authorities could take to redress the significant population shrinkage in their localities.

After the 2014 Report, local governments turned their attention to reduce the net migration outflow – both to Tokyo (as a major attractor) and neighbouring regions.

The Report said:

Such zero-sum game-like efforts do not necessarily lead to an increase in birthrates, and their effectiveness in changing the overall trend of population decline in Japan is limited.

So, rather than competing with each other for population, the Report is clear that the chronically low birth rate in Japan must be addressed if the rate of extinction among municipalities is to be reversed.

They also found that small municipalities were at risk because both demographic factors were in operation – outflow and low birth rates, whereas the larger centres were attractors for outflow from smaller areas but were still at risk because of the low birth rates.

The spatial distribution of the risk across the regions is also interesting.

In Hokkaido, “there are 117 local governments that are at risk of disappearing” and most of the local government areas on the island have been experiencing “severe population outflows” – mainly to the southern islands (particularly Honshu).

However, in the north of Honshu – Tohoku – has 165 municipalities at risk of extinction – which is the “highest number and percentage in the country, and the majority of local governments require both social attrition and natural attrition measures” – that is to stem the outflow and lift the birth rate.

In the Kanto region – centred on Tokyo – the main problem is a low birth rate which has created what the Report terms “black hole municipalities” – those that rely on population inflows given their extremely low birth rates.

Down south, Kyushu and Okinawa have the least number of at risk local government areas.

Many of the areas in the south have become ‘self-reliant and sustainable’ meaning they have been able to lift the birth rate somewhat and stemmed the outflow of people to the north.

The population decline has occupied government officials in Japan for a long time now.

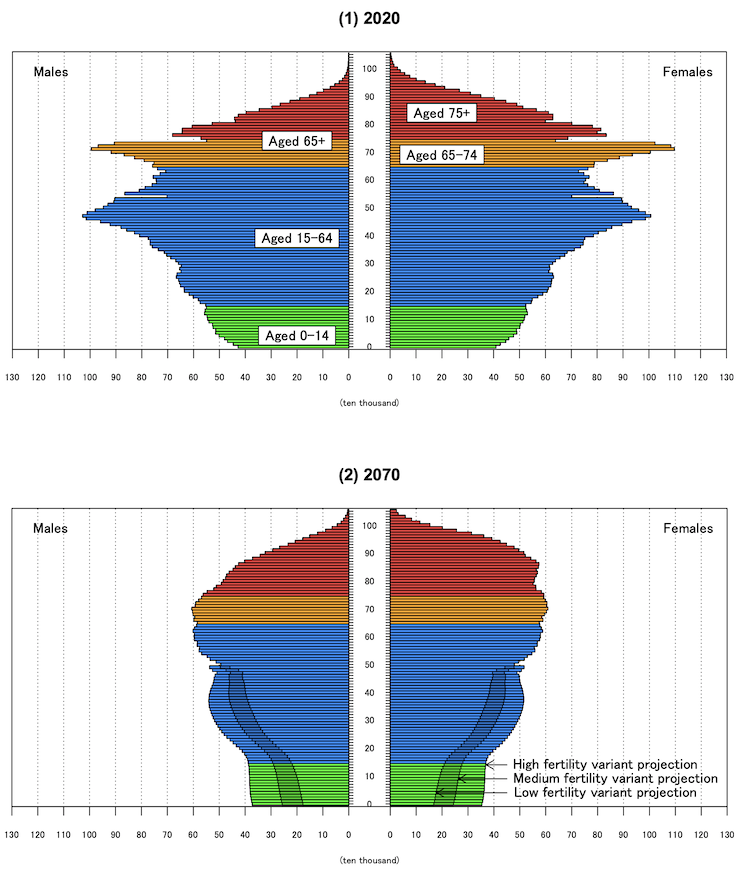

The following population pyramid graph, which embodies three fertility projections show how quickly the Japanese population will age.

The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research estimates that the dependency ratio in Japan which is – “the level of burden on 15-64 years old population to support the entire 0-14 years old population and population aged 65 years and over” – will rise (using medium fertility assumptions) from 68 in 2020 to 80.1 per cent in 2039 and 91.8 per cent in 2070.

Another way of expressing this is to take the inverse of the ratio which means in 2020 there were 1.47 persons of working age supporting each dependent person, 1.25 in 2039, and 1.1 in 2070.

In 2022, the Australian dependency ratio was 54.05 per cent which is similar to the UK and the US.

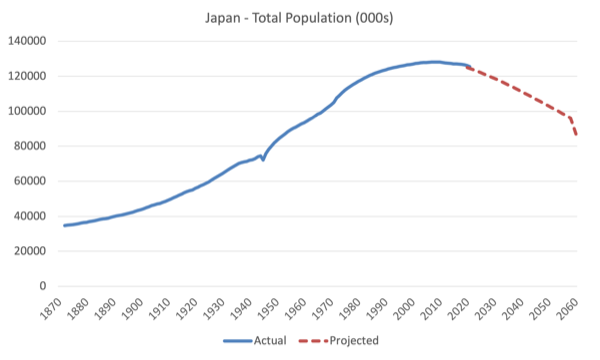

The following graphs show the Japanese population from 1872 to 2022 (actual) and then projected out to 2070 (based on medium fertility) and then split between males and females.

The male population is falling faster than the female.

In 2020, there were 94.7 males per 100 females; and by 2070 this is estimated to drop to 93.8.

And here is the projected trajectory by major age groups (medium fertility).

In January 2024, the PSC advised the Japanese government that a population target of 80 million by 2100, which they claim would allow the economy to keep growing at a rate of 0.9 per cent per annum until 2100.

This would require birth rates to rise to 1.6 kids per woman to 1.8 by 2050 and 2.07 by 2060.

So a dramatic reconfiguration of the family structure.

The problem with those aspirations is that the housing stock would not be able to cope with that increase within each house.

While the declining population and municipalities present problems of one kind, the attempt to increase the number of children per woman will be problematic for housing reasons.

The overriding issue is whether the declining population and the unequal spread of the shrinkage, which is leading to these predictions of disappearing municipalities is a major problem or an opportunity.

This IMF article from their Finance and Development magazine (March 2020) – Shrinkonomics: Lessons from Japan – demonstrates the mainstream concerns.

The IMF rehearses the usual concerns:

Meeting social security–related obligations while maintaining a sustainable fiscal position and intergenerational equity is a thorny task for Japan’s authorities and will likely require important changes to both the benefits framework and its financing structure …

Among options related to financing, a continuous and gradual adjustment of the consumption tax dominates other potential measures to finance the cost of aging, including higher social security contributions, delaying fiscal adjustment (with an implied prolonged period of debt financing), and increased health copayment rates … postponing adjustment through debt financing results in a large crowding-out of private sector investment—by up to 8 percent—with detrimental effects on long-term GDP and welfare.

So one hopes the Japanese government is ignoring this sort of advice.

First, there is no ‘financing’ problem involved here for the Japanese government.

It is the sole issuer of the yen and will be able to fund higher pension commitments, maintain health care standards and whatever without question.

The uncertainty is only whether there will be trained doctors and nurses available to person the hospitals and aged care facilities.

And based on the dependency ratios above, ensuring these real resources are available will require some planning and a set of incentives or rules that guarantee the health care sector will get access to educated and trained labour.

Second, the crowding out claims are fictional.

The debt-to-GDP ratio in Japan has been at the highest end for years and yet interest rates are always around zero.

The Bank of Japan has demonstrated it can set the interest rate at whatever level it desires.

The IMF concern is just an application of the standard mainstream macroeconomic model which is fictional at best.

The government could also decide to stop issuing JGBs altogether if it wanted.

The IMF fiction then claims younger workers will come into conflict with older dependent persons:

Growing income inequality between young and old is a concern in Japan, particularly as an increasingly smaller share of the population is asked to shoulder the financing costs for rising social security transfers.

Each generation chooses its own tax burden.

Taxes will not have to rise to ‘fund’ anything.

The Japanese government spends yen into existence because it is the sole issuer and doesn’t need tax revenue in order to do that.

There is no reason why the younger cohorts should experience increased tax burdens.

The reality is that all generations will have to reduce their material footprint to deal with climate change, a point I will come back to.

The IMF is worried that commercial banks will become unprofitable because of a lack of depositors (to screw):

Japan’s demographic headwinds constitute a challenge for all Japanese financial institutions, but particularly for regional financial firms. Because of their dependence on local deposit-taking and lending activities, Japan’s regional banks are sensitive to changes in the local environment …

Unless Japan’s regional banks find alternative sources and uses of funds, the country’s shrinking populations will necessarily lead to smaller balance sheets and declining loan-to-deposit ratios. This, in turn, will continue to put downward pressure on already low levels of profitability.

Is that a problem?

I can’t see how it can be other than for the shareholders of the banks.

The Japanese government could easily nationalise the banking system and ensure it works in the interests of the customers rather than to make profits for the shareholders.

This also relates to what I will say about degrowth later.

The IMF also thinks that monetary policy will become ineffective because interest rates will have to remain low.

This is not a problem at all and the Bank of Japan has already demonstrated over a few decades what happens when interest rates are around zero – nothing much!

Three final points.

First, the real problem of the ageing population is productivity.

The younger generations will have to be more productive than the older generations to maintain material standards of living given there will be less producers and more dependents.

That suggests even more funding should be diverted into education and training whereas the IMF wants less government spending on these assets as part of its ‘consolidation’ approach.

The way to make the population more productive is to invest heavily in the skills and knowledge of the people.

That should remain a priority for the Japanese government.

But, second, the productivity point has to be seen in the context of climate adjustments.

Japan’s population dynamics actually provide it with the opportunity to lead the way into a degrowth future.

If there are less people overall then less needs to be produced.

I have previously discussed that the majority of small and medium businesses in Japan are owned by people above 70 years of age and there is a bias against selling the businesses outside the family.

Yet, the kids tend to want to avoid taking over the businesses.

The government is obsessed with finding ways to stop these businesses closing down when the owner gets too old.

But they could see it as an opportunity to reduce the scale of enterprise.

While we all have favourite little shops in our localities (and certainly I haunt a few places when I am living in Kyoto each year).

But we would find other favourites soon enough.

So while the younger people should be given the best opportunities to be productive in the narrow (bean counter) sense Japan should relax and accept that its material standard of living will have to decline anyway to deal with the climate challenge.

And if that adjustment doesn’t have to come with increased unemployment – because the supply of labour is shrinking anyway – then that will be much easier than it will be for nations with younger populations who have to undergo the same transition away from carbon and growth.

Third, one of the projects I am involved in concerning Japan is working out how to increase decentralisation.

It is imperative that the government rebuilds populations in the regions by reducing the density in the major cities, particularly the Kanto (Tokyo) region.

A major reason for this is to reduce the damages that will be incurred when the next East coast earthquake hits Japan, particularly if it is concentrated in the Tokyo Bay area.

The other major reason is to ensure these declining municipalities can achieve some sustainability as noted above.

A major impediment to decentralisation attempts is the relative poverty of public transport outside of the links between the major cities – which are first class.

The Japanese government should be investing in high speed rail beyond the railway network that runs down the spine of the main island.

Conclusion

Japan has been my real world laboratory for a few decades now.

And its population dynamics ensure it will remain that way.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“A major impediment to decentralisation attempts is the relative poverty of public transport outside of the links between the major cities – which are first class.”

And the lack of paid work in rural Japan – back to the Job Guarantee which helps push labour hours back to the periphery as well as monetary flow, rather than dragging it all to the centre under ‘gravity’ beliefs.

Mainstream agglomoration narratives would have all of us living 120 storeys high in a square kilometre in the middle of a single city.

Dear Neil Wilson (at 2024/04/29 at 4:41 pm)

You wrote:

In fact, there is no shortage of work in the regions. Paid work at that. Employers find it hard to attract labour.

best wishes

bill

I do hope Japan continues to manage the Demographic Transition Phase 4b and show the rest of the industrialised world that, with a shift to sustainable development. i.e. a degrowth model, it is manageable without the panic that low or zero GDP growth gives conventional political economists and many western governments.

We do not have much idea as to how AI will affect productivity in the service sector, though it will clearly continue to reduce labour requirements in the productive economy, including much agriculture, so we cannot accurately estimate the levels of immigration required to maintain overall productivity, let alone in sustaining the tax take.

Even if the % GDP that goes to the retired population increases from 10-20% (as has been estimated for the UK – i.e. from £160bn to £330bn in 2050) as old age pensions are spent rather than saved, so feed a multiplier effect in the day to day economy.

A compensatory increase in education and training is then essential, as proposed, and would then benefit a different demographic segment. Intergenerational competition is highly undesirable socially and is politically divisive.

Scotland has 32 local authorities and is very much centralised, suffering from that in terms of democratic deficits, but Finland has over 310 with pretty much the same 5m+ population.

The very smallest Finnish municipalities are below 20,000 people, yet this decentralised nation allocates 40-50% of total government expenditure via these municipalities.

There seems no obvious reason for the level of decentralisation in Japan to reduce with a stable or falling population, given Finland’s success as a social democracy, by most metrics.

In landscape and terrain terms Japan and Finland both often have local populations separated by mountainous terrain, so the traditional independence of local communities ought to enable and support a level of resilience and capacity for self management.

It might require a restructuring and evolving relationship between central and local government, but it can be done.

“We do not have much idea as to how AI will affect productivity in the service sector, though it will clearly continue to reduce labour requirements in the productive economy”

We do. What is called AI is mostly marketing fluff – since the real innovation of this cycle (the transformer algorithm) is really just a sophisticated autocorrect. At best it is a force multiplier, not a replacement. Therefore it will have the same effect as other human augmentation technology. It will make some things cheaper, and increase their availability.

It will be the same as other computerised technology – which is to hoover up more and more people and not really improve overall productivity as much as predicted and probably not as much as it ought to have done.

Can you please then provide an estimate, preferably referenced, of how far AI will impact the service sector, and the degree to which overall employment levels will be affected ? … which was the context.

I wonder why young Japanese women don’t want babies. I wonder if it’s the same reason as young South Korean women.

I think China is leading the way with infrastructure. Surely that model of success there from the last 30 years, resulting in rapid modernity is a sign to the west that hey, your neoliberalism is not working mate.

Japan is certainly up there leading too, but i can only cross my fingers hoping the neoliberalism parasite does not become epidemic there, as it is a pandemic of lies and punitive management in the rest of the west.

China has made big strides in improving the well-being of its people over the last 46 of so years, both in absolute and comparative terms, but starting from a very low base, as it wrecked the lives and killed millions of its own in the previous post-war years. Its city development and intercity road and rail network is amazing (no nimby planning holdups), made advances in education and health (though so have other places) and is making progress on greener energy, though its growth and export model makes that difficult. Its housing boom certainly provided homes, a surplus of them, and if you think we’ve (the UK) got problems with shoddy build and materials then China will shock. But, it’s got the same problem of a depopulated, left behind countryside plus environmental destruction, as elsewhere, with the Eastern seaboard megacities drawing millions of migrant parents leaving their one child behind to be brought up by grandparents or boarding schools. And despite the absorption of its working age population into building, exporting, security and low end precarious employment, it still has an unemployment problem. And as well as the emptying small towns and countryside problem that Bill presents for Japan, it also shares the low birth rate issue of Japan, SK, Italy, lots of others. We all need to share insights to deal with degrowth.

@Carol Wilcox primarily housing cost and work pressure and consequences of falling off the treadmill for both men and women. SK is a great country for a tourist, but rather more pressured for its own people. Nevertheless, in terms of progress over a short period, it’s also definitely a rival to China (and Japan). Taiwan also, though I say that without having personal experience.

Well, I would be quite happy to live in Japan to up the numbers! If only….

Spending on productivity improvement will be inflationary, given the tight labour market caused by population decline.

A hypothetical: We replace, let’s imagine, 10% of taxi drivers with driverless robo-taxis. Great! We’ve improved productivity.

But how are the robo-taxis financed in a non-inflationary manner, given that workers will have to be diverted from other tasks to manufacture the robo-taxis?

During a labour shortage, the diversion of existing labour to work on productivity improvement projects will be inflationary.

Hi Bill, I’m confused at the claim that there is insufficient housing in Japan for more kids when there are articles like this one? Are you saying all the empty houses are too small, if so what’s the source?

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/may/01/akyia-houses-why-japan-has-nine-million-empty-homes

I don’t think I understand John B.’s point about inflation in the context of the hypothetical pesented.

Wouldn’t resources effectively move from making 10% of conventional taxis to making the driverless replacements, assuming the technology and training were available?

If so there should be no extra demand for the limited resources, hence no impact on inflation.

Hi Bill,

I would have to disagree with your suggestions for high speed rail and business closure. While you are right to highlight public transport in rural areas is important – I think a desire for high speed is counterproductive. Continued expansion of the Shinkansen network under 1970s logic is simply exacerbating the urban drift, raising ticket prices and undermining the important local services. It appears that infrastructure Japan needs is exactly what it is destroying.. narrow streets, local train routes, and the natural ecosystems that rural economy relies on.

While I see your point regarding closure of SMEs.. and some must certainly befall this fate.. I think you underestimate the social and cultural value these places hold. These businesses could be a local sento, or kissa, or independent convenience store, the bedrock of a community. Without some effort to pass these on to the next generation, this value will be lost and readily consolidated by the market economy and larger corporations.