Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Growing evidence that Covid has incapacitated a huge number of workers with little policy response forthcoming

Regular readers will know I have been assessing the evolving data concerning the longer-run impacts of Covid on the labour force. As time passes and infections continue, our immediate awareness of the severity of the pandemic has dulled, largely because governments no longer publish regular data on infection rates, hospitalisations and deaths. So the day-to-day, week-to-week tracking of the impacts are lost and it is as if there is no problem left to deal with. But data from national statistical agencies and organisations such as the US Census Bureau tell a different story and I am amazed that public policy has not responded to the messages – mostly obviously that in an era where populations are ageing and the number of workers shrinking, we are overseeing a massive attrition rate of those workers who are being forced into disability status from Covid. It represents a massive policy failure and a major demonstration of social ignorance.

The latest data from the British Office of National Statistics (released March 12 2024) – LFS: Econ. inactivity reasons: Long Term Sick: UK: 16-64:000s:SA – is fairly clear.

The accompanying labour market report – Labour market overview, UK: March 2024 – notes that:

The UK economic inactivity rate for those aged 16 to 64 years was 21.8%, above estimates of a year ago (November 2022 to January 2023),and increased in the latest quarter.

The detailed analysis shows that “Since comparable records began in 1971, the economic inactivity rate had generally been falling; however it increased during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and fluctuated around this increased rate.”

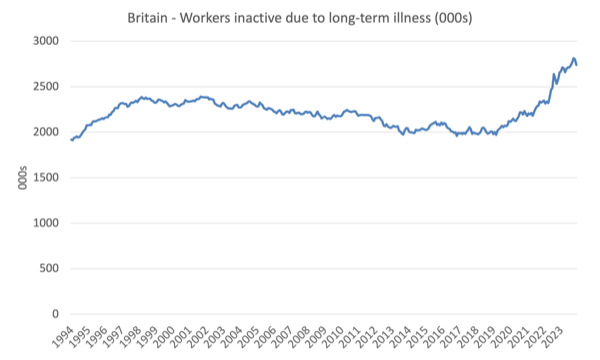

The ONS breakdown the inactivity data by reason (retirements, study, sickness, etc) and the following graph shows the workers aged 16-64 years who have become inactive because of long-term sickness.

The following graph captures the movement in that data since 1994.

Since the beginning of 2020, the number has risen by 629 thousand or around 1.8 per cent of the available labour force (1.4 per cent of the total population aged between 16 and 64 years of age.

Given the timing of that increase, it is unlikely to have been driven by anything other than the impacts of Covid infections.

Adding those who have died from Covid only worsens the labour market impact.

The data is interesting because it also allows us to surmise regarding the impacts of austerity and cutbacks to the NHS in Britain.

Many people have indicated that the rising inactivity rate in Britain is due to these neoliberal shifts in government policy.

I clearly have sympathy with their concerns but the data shown above suggests that over the 20 odd years leading up to the pandemic, the number of workers being forced into inactivity from long-term illness was declining.

The shift came with Covid and I think that is indisputable.

There is other data, which I will report on another day that suggests a rising incidence of workers who are still working but are also chronically ill in one way or another.

Perhaps that rising incidence is a reflection of the increased austerity and declining standards within the health system.

The Covid impact can be seen in many other countries, which means that the British-specific issues surrounding inactivity are further put into context.

In June 2022, the US Census Bureau, for example, specifically added questions to the their – Household Pulse Survey – which aims “to produce data on critical social and economic matters affecting American households.”

The additional questions specifically allows the survey to generate information regarding “COVID-19 vaccinations and long COVID symptoms and impact”.

You can find more information about these additions to the HPS from the – National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

The agencies involved claim that the extra data “was designed to complement the ability of the federal statistical system to rapidly respond and provide relevant information about the impact of the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S.”, although given the findings and the absence of a coherent policy response, one has to conclude that the authorities have given scant regard to the information generated, much to the detriment of the population.

The NCHS provide an extensive dataset – “Estimate of Post-COVID Conditions” – the most recent observations published take us up to March 4, 2024.

The data shows that in June 2022, 40.3 per cent of Adult Americans had been infected with Covid.

By February 2024, that proportion had risen to 59.6 per cent and the trend was rising.

Back in June 2022, when these questions were added, 14 per cent of all adult Americans had experienced long COVID, defined as “symptoms that lasted three months or longer”.

By February 2024 (the latest data), that proportion had risen to 17.4 per cent.

The HPS also asked what proportion of American adults were “CURRENTLY experiencing post-COVID conditions (long COVID)”, which included adults who have had “COVID, had long-term symptoms, and are still experiencing symptoms.”

In June 2022, the proportion was 7.5 per cent, and in February 2024, the proportion was 6.7 per cent.

Further, when asked about “any activity limitations … from long COVID, among adults who are currently experiencing long COVID and among all adults”, the numbers were:

– June 2022: 5.9 per cent.

– February 2024: 5.5 per cent.

And, when asked about “significant activity limitations … from long COVID, among adults who are currently experiencing long COVID and among all adults”, the numbers were:

– June 2022: 1.8 per cent.

– February 2024: 1.7 per cent.

The incidence of each of these categories were spread across the age spectrum, which mitigates against just concluding that the issues pertain to the elderly.

In fact, older workers had lower incidences.

A Brookings Study from August 24, 2022 – New data shows long Covid is keeping as many as 4 million people out of work – reported on the first release of this new dataset.

It found then that:

– Around 16 million working-age Americans (those aged 18 to 65) have long Covid today.

– Of those, 2 to 4 million are out of work due to long Covid.

– The annual cost of those lost wages alone is around $170 billion a year (and potentially as high as $230 billion).

At the time, there were various estimates provided by different organisations of “the percentage of people with long Covid” that “have left the workforce or reduced their work hours”.

You can see those studies cited in the Brookings report.

The Brookings authors also predicted that:

These impacts stand to worsen over time if the U.S. does not take the necessary policy actions.

Many more recent research studies have found that work impairment is a signficant issue arising from Covid.

Lancet has, for example, published many more recent studies showing among other things that those “enduring impaired work ability … represents a huge burden” (Source):

There are studies that have found that many employers have sacked or made redundant workers who report long Covid symptoms that impair their ability to currently work (Source):

A Lancet survey (March 11, 2023) – Long COVID: 3 years in – concluded that:

… at least 65 million people are estimated to struggle with long COVID, a debilitating post-infection multisystem condition with common symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, impairing their ability to perform daily activities for several months or years.

That is “10–20% of cases and affects people of all ages, including children, with most cases occurring in patients with mild acute illness.”

Further, “an estimated one in ten people who develop long COVID stop working, resulting in extensive economic losses.”

So what has been the policy response?

The evidence suggests that:

The outlook for such care appears only to have worsened. Primary care has suffered in many countries, waiting lists have lengthened, and health systems are struggling. Education and awareness on the clinical management of long COVID in primary care remains insufficient and inequities in care continue. Reliable and authoritative platforms to support and guide patients are still absent in many places. Delays in care and support prolong and exacerbate the symptoms of long COVID. There is little sense that social supports—particularly around employment—have been introduced to meet the needs of patients.

In Australia, it is hard to find a coherent policy response.

Federal and State governments have effectively abandoned any attempt to reduce infection rates through simple measures such as mask mandates in public spaces.

I am at airports and in planes almost every week and very few people wear masks despite the ongoing infections and long-term implications.

Over the weekend, a UK Guardian report (March 24, 2024) – Longest sustained rise in people too sick to work since 1990s, says thinktank – summarised a Resolution Foundation analysis (that doesn’t seem to be public yet) of the latest ONS data on inactivity.

Readers were told that:

… economic inactivity due to long-term sickness – when people aged 16-64 are neither in work nor looking for a job because of a health condition – had increased in each year since July 2019, the longest sustained rise since 1994 to 1998

The policy response?

A “crackdown on welfare claimants”.

As you were!

Conclusion

While most progressives have ‘moved on’ from the Covid issue, even pumping out articles and books which amount to a denial of the problem, the evidence base is growing as time passes and more data is made available.

Yes, the short-run data that was available on a daily basis is now suppressed by government agencies.

But the longer-term data based on survey evidence is becoming richer in temporal scope and detail, which is allowing researchers to answer many questions.

What is pretty obvious is that Covid is leaving a legacy of a growing proportion of workers that can no longer work and earn incomes.

This is quite apart from the complex damage that the disease is having on their health and life expectancy.

I am amazed that the policy responses have been so pathetic.

Even the bean counters who continually rail about ‘costs’ and ‘budgets’ should realise that the long-term consequences of having a growing proportion of the population incapacitated and dependent on welfare support, are silent.

Why?

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It would be interesting, if possible, to also have long covid data from China, where, following the ending of zero-covid restrictions in December 2022, there was nationwide mass infection, with infection rates much higher than the high rates of the US/UK, though with the omicron variant (wiki extract: As of 6 January 2023, the infection rate of Henan province had reached 89 percent, according to Kan Quancheng, director of the province’s health commission. This percentage of infections meant that roughly 88.5 million people had contracted COVID-19 within just one month). So that’s about the same number of people with covid in just one province as the population of Germany.

I recall a lecture from an epidemiologist from Porton Down almost two decades ago, where he explained the ‘Trojan Horse’ principle in biological warfare – essentially an engineered agent with high infectivity and minor initial symptoms, but having the capability to incapacitate and disable victims months or years after the initial infection. He claimed that if the common cold could be weaponised, humanity would face an existential crisis.

Whether SARS2 has been from a laboratory construct or a natural spillover is still unconfirmed, but the emerging disease affecting many critical systems – cardiovascular, brain, nervous, kidney function and GI – is somehow diminished by the term ‘Long Covid’. The formation of Lewey Bodies in nerve cells – often a precursor to Parkinson’s and Dementia – following even asymptomatic infection in many individuals, is particularly concerning. Given the critical state of health systems across the world even before this outbreak, the future, as you note, looks bleak indeed. There is no coherent policy – and now no mitigation or NPIs – or any public health advice – and re-infection rates are still rising, despite – or perhaps as a result of – a vaccination programme with sub-optimal drugs i.e non sterilising agents.

The pandemic is far from over.

Certainly, currency-issuing governments have made full use of their fiscal ability to fund the cost of these past four years, but I would argue that much has been wasted. There were temporary hospitals constructed (Nightingale field units) that were aimed at respiratory dysfunction in the first year, barely used then dismantled or repurposed the following year. We had a network of specialist infectious disease and isolation hospitals in the UK that managed victims of Spanish Flu, TB and Polio – but this was dismantled and the buildings and land sold off for development.

Replacing these hospitals now – with all the attendant facilities, equipment and trained staff – would likely cost as much if not more than what has already been spent on the pandemic response, but I suggest such a programme is essential, given the very real possibility of further outbreaks and a catastrophic rise in serious or refractory health conditions associated with this virus.

Try to get in to see John Campbell, Bill

https://www2.sl.nsw.gov.au/archive/discover_collections/history_nation/terra_australis/letters/campbell_john/index.html