Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Britain’s future is being compromised by the massive increase in long-term sickness among the working age population

When I was in London recently, I noticed an increase in people in the street who were clearly not working and looked to be in severe hardship from my last visit in 2020. Of course, in the intervening period the world has endured (is enduring) a major pandemic that has permanently compromised the health status of the human population. The latest data from the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) – Labour market overview, UK: February 2024 (released February 13, 2024) – provides some hard numbers to match my anecdotal observations. Britain has become a much sicker society since 2020 and there has been a large increase in workers who are now unable to work as a result of long-term sickness – millions. Further analysis reveals that this cohort is spread across the age spectrum. A fair bit of the increase will be Covid and the austerity damage on the NHS. Massive fiscal interventions will be required to change the trajectory of Britain which not only has to deal with the global climate disaster but is now experiencing an increasingly sick workforce, where workers across the age spectrum are being prematurely retired because they are too sick to work. With Covid still spreading as it evolves into new variations and people get multiple infections, the situation will get worse. It is amazing to me that national governments are not addressing this and introducing policies that reduce the infection rates.

Covid costs

During the first few years of the pandemic it was easy for skeptics to wax lyrical on Twitter and write books condemning any Covid restrictions because there was so much uncertainty and noise about the disease and limited data available.

So you had people promoting the so-called Barrington Declaration which essentially said that we should just all get Covid, no worries, except those who were very vulnerable to respiratory diseases.

They had no plan on how the rest of us would service the very vulnerable, given we would be bringing the disease into nursing homes, hospitals etc.

But, hey, minor detail.

And we saw first hand the massive death rate in old age homes and the rising incidence of infections in hospitals.

An old friend of mine recently went into hospital with a broken hip after a fall and never came out – she caught Covid in the hospital and died there.

Anyway, more data is coming available and the picture is becoming a little clearer – it is a very damaging disease and the conjecture from research epidemiologists is now suggesting that peak human health has now passed as a result of the way Covid attacks all our major organs.

The research notes that health science for decades was winning the war against deadly diseases such as small pox, typhoid etc, but with Covid no such success will be possible and the human health condition is now permanently compromised.

And, we will start to add the costs of the ‘liberal’ policies that are now in place, which allow the disease to spread freely in the population.

And we are too stupid to self regulate to avoid getting infected in the first place or spreading it if we are infected.

The latest evidence of the dramatic costs that societies will bear into the future as a result of allowing the disease to spread so widely comes with the latest release of labour force data from the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) – Labour market overview, UK: February 2024 (released February 13, 2024).

First, some concepts.

For statistical purposes, the statisticians divide the population into categories:

1. Working age (16 years + in Britain) or not.

2. Then within the working age population, you are either active or not.

3. If you are employed or actively looking and available for work then you are counted as active (or in the Labour Force), otherwise, you are considered to be inactive (or Not in the Labour Force).

4. The activity (or labour force participation rate) is simply the proportion of the labour force relative to the working age population

5. The inactivity rate is the proportion of those not in the labour force as a percent of the working age population.

Clearly, those who are inactive include those in retirement who have chosen to exit the labour force.

But it also includes those of working age who are unable to work, which is what this post is about.

In its latest release, the ONS note that:

The UK economic inactivity rate (21.9%) for those aged 16 to 64 years was largely unchanged in the latest quarter but is above estimates a year ago (October to December 2022). The annual increase was driven by those inactive because they were long-term sick, which remains at historically high levels.

In an earlier release (July 26, 2023) – Rising ill-health and economic inactivity because of long-term sickness, UK: 2019 to 2023 – the ONS note that:

The number of people economically inactive because of long-term sickness has risen to over 2.5 million people, an increase of over 400,000 since the start of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic …

Between 2016 and 2019, there was a small fall in the proportion of people who reported no health conditions, decreasing from 71% to 69%. However, from the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, this downward trajectory accelerated so that in January to March 2023, only 64% of working-age people reported having no health conditions. This is an absolute drop of 2 million since the same period in 2019.

The July release also allowed us to examine the number of people who were economically inactive because of long-term sickness by age group.

This Table summarises the situation for 2019 and 2023.

They are frightening figures and clearly the fact that British workers have become increasingly unable to work due to long-term sickness has accelerated since the Covid pandemic and is spread across the age spectrum, rather than being just older workers.

| Age Group | 2019 (000s) | 2023 (000s) | Change (per cent) |

| 16-34 | 383 | 547 | 43.0 |

| 35-49 | 488 | 568 | 16.4 |

| 50-64 | 1,088 | 1,375 | 26.4 |

| Total | 1,959 | 2,490 | 27.1 |

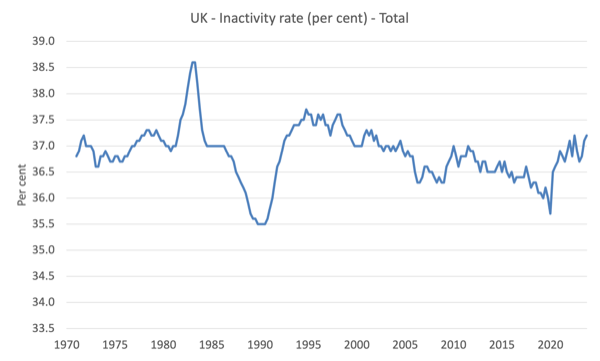

Using the most recent data (released February 13, 2024), the following graph shows the UK inactivity rate (per cent) for those 16 years and over from the March-quarter 1971 to the December-quarter 2023 (latest data).

We see some interesting patterns.

In the early 1980s, when the Thatcher government turned on the manufacturing and coal mining sectors, many workers were pushed out of the workforce into inactivity.

They were mostly older males, who had been the backbone of industry in the post-WW2 period.

From the mid-1990s, inactivity fell again, largely due to the increased participation of females in the labour force.

In gender terms, the male inactivity rate has climbed from 16 per cent in the March-quarter 1971 to over 33 per cent in the December-quarter 2023.

For females, it was 55.3 per cent in the March-quarter 1971 to 41.1 per cent in the December-quarter 2023.

So quite a dramatic shift in participation between males and females.

Further, the major events over this period in the early 1980s, the GFC and the pandemic have been dominated by shifts in male participation rather than female participation.

This downward trend was halted by Covid.

Since the March-quarter 2020, inactivity rates in the UK have risen from 35.7 per cent to 37.2 per cent – which means that 1,191 thousand workers have left the active labour force since the pandemic, most due to long-term sickness (more than 700 thousand).

59.5 per cent of those who have become inactive since the pandemic began are males.

Between the March-quarter 2020 and the December-quarter 2023:

1. 16-17 year olds – inactivity rose by 0.7 points.

2. 18-24 – rose by 4.7 points.

3. 25-34 – rose by 0.6 points.

4. 35-49 – fell by 0.2 points.

5. 50-64 – rose by 1.0 points.

6. 65+ – rose by 0.4 points.

So the increase in activity since the pandemic up to the December-quarter 2023 is spread across the age groups.

Around 50 per cent of the increase is accounted for by people who are aged below 65 years, so is unlikely to be associated with planned retirement.

At this stage, the data does not allow me to decompose the sources of the rising long-term illnesses that are forcing workers out of the labour force.

Almost certainly, a large proportion of the change is due to complications arising from Covid infections.

However, with the deliberate undermining of the NHS in Britain by the years of fiscal austerity, the decline in the quality of health care is also likely to be an important factor.

Of course, the two factors are also intertwined.

The longer term impacts of this will increasingly cripple the British economy.

Firms will increasingly find it harder to find workers.

With an ageing population, the younger workers will need to be more productive than their parents, yet many are being forced out of the workforce due to long-term illness.

And you can bet that the ‘sound finance’ gang will be out in force attacking any fiscal activism that is forced to provide income support for these workers who are no longer able to work.

And their endeavours will just make the situation worse.

A significant proportion of the rising inactivity could have been prevented by better health policies relating to Covid.

Allowing the virus to spread as per the Barrington mob has made the problem worse.

When I was in London recently, I stood out because I was the only person that was still wearing a mask in closed situations (shops etc).

Such a simple act, which clearly reduces infection transmission, and almost no-one is doing it.

In this context, it was interesting to read the Op Ed by Will Hutton in the UK Guardian (February 18, 2024) – The first step to our economic liberation is to tear up these crippling fiscal rules – which exhorts the British government to abandon its austerity mindset that is reinforced by trying to follow strict fiscal rules.

In that sense, his challenge applies to both the Tories and the Labour Parties.

He points out correctly that the forthcoming challenges for government are of a scale probably not seen in the past given “the last 14 years of misgovernance”, although he is careful to note that the behaviour that has created this issue reaches “back for decades” – like ever since the Monetarists took over as the dominant economic school of thought.

It is not just a matter of dealing with degrading infrastructure and service delivery.

New challenges presented by the the climate emergency requires much more investment than would be necessary to ‘fix’ the past damage up.

Hutton, given his political biases attacks the Tories, going back to Thatcher and then Osborne, then Brexit.

But he should have mentioned the pre-Thatcher Labour government with James Callaghan and Dennis Healey in charge – they were the first to articulate ‘sound finance Monetarism’ while in government.

And don’t forget Blair and Brown, the latter who tried to claim credit for his ‘light touch’ regulation (read: no regulation) of the financial sector, which undoubtedly made the GFC much worse in Britain.

And don’t forget the current Labour team – Starmer and Reeves – who are as obsessed with fiscal rules as any Tory has ever been.

Even to the point of abandoning investment in necessary climate policies, which will rebound terribly in the years to come.

Hutton gets that I think when he writes:

The country is plainly minded to give Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves the opportunity to govern …

Now is not the moment to close down options and surrender ground to a right that is trying to lock them into the same paradigm of failure it occupies – cheered along by a rightwing popular press more out of kilter with public opinion, as former editor of the Sun David Yelland says, than at any time since the 1930s.

Indeed, and we will wait and see.

But if modern history tells us anything, the Labour leadership will not be able to resist kowtowing to the ‘City’ and thus surrendering to the ‘right’

Conclusion

Massive fiscal interventions will be required to change the trajectory of Britain which not only has to deal with the global climate disaster but is now experiencing an increasingly sick workforce, where workers across the age spectrum are being prematurely retired because they are too sick to work.

With Covid still spreading as it evolves into new variations and people get multiple infections, the situation will get worse.

It is amazing that national governments are not addressing this and introducing policies that reduce the infection rates.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Around 50 per cent of the increase is accounted for by people who are aged below 65 years, so is unlikely to be associated with planned retirement.”

That’s captured by sequence LF6B at the ONS.

You can see that peaked about 2010 and has been declining ever since.

I keep an eye on Table 11 in the Labour Market overview (you have to download the PDF to view it), which has a break down of economic activity by reason as well as the ever useful LFM2 sequence “inactive – wants a job”.

“At this stage, the data does not allow me to decompose the sources of the rising long-term illnesses that are forcing workers out of the labour force.”

The ONS did some experimental statistics on the types of conditions that are causing economic inactivity published in a report “Rising ill-health and economic inactivity because of long-term sickness, UK: 2019 to 2023”

There is a dataset associated with that report that breaks down the health conditions by category. The biggest increase being ‘other’.

I’d say covid has also exacerbated the number of working age people, not sick of themselves, but reducing work hours or dropping out of the workplace to take care of family. An aging population also contributes to this, as does the lack of affordable paid outside care help. The terrible state of the rental housing sector, particularly in London, is also undoubtedly a factor behind the number of people in severe hardship on the streets.

Re. Will Hutton’s tearing up of the fiscal rules, the headline led me to read his article in optimistic anticipation, but what he actually proposes is not greatly different from Labour. Labour will ‘close the gap on day to day spending over 5 years’. Hutton would have a balanced budget for day to day spending ‘over the economic cycle’.

In addition to the damage caused by the epidemic and the unforgivably cack-handed way the UK government has dealt with it, chronic underfunding of the NHS has exacerbated workforce attrition due to stress and demotivation, creating a viscious spiral of decline, and of course a worsening situation for those still of working age who need treatment, operations, or therapy, whether Covid-related or otherwise, in order to be able return to work.

It’s understandable to anticipate an eventual return to a prior state of better funding, performance, and outcomes for the UK health service, a return to a state of “normality” if you like, but I’m almost certain now that this will never come, given the present and likely future political landscape, societal atomisation, and general resignation in the UK.

Looking around the world, and back in time, it’s astonishing how much adversity human beings can endure, yet still survive in some form or another, without complaint. We in the UK still have a lot further to fall, if it came to it.

But what hope is there for a nation whose national motto is “musn’t grumble”?

Over the years I have given much positive attention to the ideas of Will Hutton.

However, as one with no illusions about the nature of British politics, our useless, self-seeking Establishment and the poisonous effects of our generally right wing and frequently foreign or tax-exile owned media, I am very disappointed that he chooses to continue to be very insulting to Jeremy Corbyn, who at the very least gave people a vision of better possibilities for our country suffering the ravages of neoliberal incompetence and lies.

Just a thought…

The rise in inactivity for the young, could it represent mental health problems related to “failure to launch” syndrome….internet and gaming addiction among young people, anxiety, hikikomori type syndrome. Basically young people not leaving home and facing adult life. Anecdotally, I see examples of this around me. Financial insecurity and poor job opportunities is part of this surely..

Cs, problems, as a rule, of the economy and system come first than individual problems.

The addiction you mention is a coping mechanism for many people when faced with a shitty world.

If you want to know more about addiction you should read “The Myth of Normal” by Gabor Maté, it explains so much about the woes that societies are going through, including addiction.

The exacerbation of addiction is yet another example of how neoliberalism is destroying society and, therefore, individuals.