I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

How interest rate rises undermine our climate adaption

It’s Wednesday and I have a few observations on a few things today. I have written before about how the rising interest rates in many nations, far from being deflationary, have demonstrably increased inflationary pressures. The two pathways that this impact occurs are: one, the boost to wealth among creditors coupled with significant proportions of fixed-rate mortgages provide the equivalent of a fiscal boost, and, two, the direct impact on costs to firms via their overdrafts and on landlords. The former just pass the unit cost rise on to consumers, while the latter increase rents, which feed into the CPI. But I have also been tracing another negative outcome from the interest rate hikes – the impact on investment in renewables. Here are some notes on that followed by some music with a renewable energy theme.

RBA thinks interest rate hikes will slow housing market – the data says otherwise

Yesterday (October 3, 2023), the Australian Bureau of Statistics published the latest – Lending indicators – which tell us about new borrowing for “housing, personal and business loans”.

Earlier in the week (October 2, 2023), we learned that that after a modest dip, house prices in Australia are now heading towards record highs.

The Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) article – Australian house prices on track to hit new record high, latest property data shows – provided a summary of the latest data.

In September, “housing data showed prices rose 0.8 per cent nationally in September, led by Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth, where housing supply remains about 40 per cent below the five-year average.”

The ABS data release yesterday is consistent with the housing price data.

It shows that in August 2023, new loan commitments:

1. rose by 2.2 per cent for housing.

2. rose by 6.1 per cent for personal loans.

3. rose 17.2 per cent for business construction.

4. rose 10.8% for business purchase of property.

Over the 12 month period, these aggregates declined, but new loan commitments have turned since March 2023.

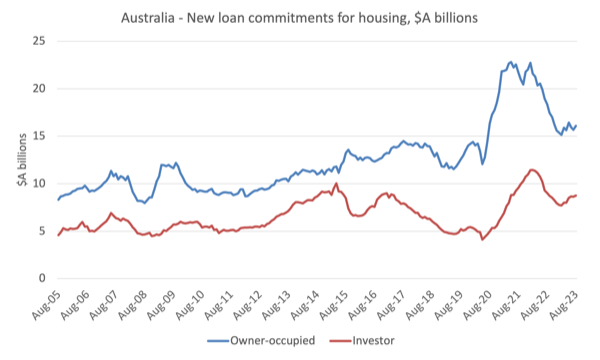

The following graph shows the seasonally-adjusted new loan commitments for housing (owner-occupied and investment properties) since 2005 to August 2023.

The notable boom during the pandemic was driven in no small way by the low interest rates, but, coupled with the statements made by the then RBA governor that the central bank would not be lifting rates until 2024.

He later denied saying that but everyone heard it and they borrowed on that basis.

Then the RBA started hiking in May 2022 and 12 increases later the target rate is 400 basis points higher.

All purportedly to take the steam out of the housing market and reduce borrowing.

The graph shows that the rate hikes probably reduced borrowing for housing for a while but that now new loan commitments are on the increase again.

So on the face of it, the RBA monetary policy changes are not impacting the way they claimed.

Which is no surprise to anyone who understands the uncertainty attached to these impacts.

The RBA likes to talk as if it knows what it is doing.

The fact remains that there are complex and contradictory forces that are triggered by interest rate changes and the RBA does not know what the net effects will be.

It is not to say the rate hikes are not damaging to specific groups in the economy – typically low-income borrowers on variable rate mortgages, who also carry a lot of credit card debt because their incomes are not growing.

But in a macro sense, the housing market is heating up again.

Monetary policy changes undermine future sustainability

One of the benefits of the period of low interest rates before this recent hiking phase was that funding for renewable energy investments was stimulated.

The cost of funds is only one factor influencing investment but it is clear from the data that when interest rates were low, the renewable energy sector expanded more quickly than most people had originally anticipated.

The other major factor stimulating that expansion was the technological developments which shifted the competitiveness of energy sources towards renewables.

I read a report a few years ago – Projected Costs of Generating Electricity – 2020 Edition – which was published by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

These reports come out every five years and:

It presents the plant-level costs of generating electricity for both baseload electricity generated from fossil fuel and nuclear power stations, and a range of renewable generation – including variable sources such as wind and solar.

The most recent edition found that:

… the levelised costs of electricity generation of low-carbon generation technologies are falling and are increasingly below the costs of conventional fossil fuel generation” – which is one of the reasons the shift in the generation mix has been shifting quickly to renewables.

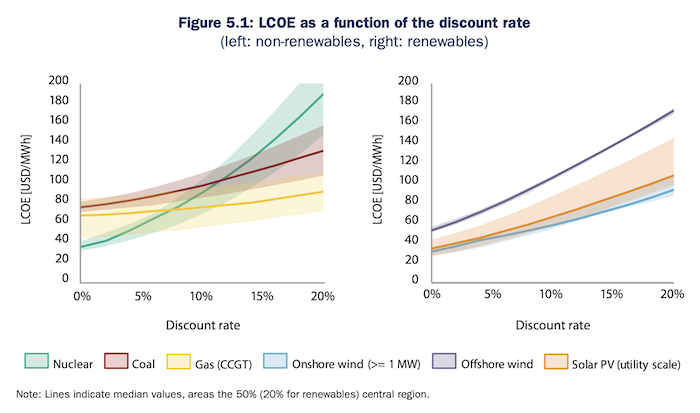

This graphic (Figure 5.1 reproduced) shows the sensitivity of the different energy sources to variations in the ‘discount rate’ or interest rate, which they note “affects several aspects of LCOE costs, such as construction, refurbishment and decommissioning expenses”.

If you study the left- and right-panels, you see that gas technologies are hardly impacted by the sort of interest rate rises we have observed over the last year or more, whereas the renewable technologies are significantly impacted in terms of their “levelised cost of electricity”.

The Report notes that:

Within the group of flexible baseload plants, i.e. nuclear, coal and natural gas-fired CCGTs, the latter are the least susceptible to changes in the discount rate. The average costs of the median case are increasing by around 40% when comparing the 0% and 20% discount rate cases … The variable renewable energy technologies wind and solar exhibit relatively high upfront and low operating costs – as no fuel costs occur, the latter consists only of O&M and refurbishment costs. These properties make them especially susceptible to changes in the discount rate.

But the IEA Report was published in 2020.

So what about now?

In April this year, the Lazard Group, which is a long-standing, global financial services company published their latest estimates of the – LCOE – which confirmed that the “cost … and availability, of capital … is particularly significant for renewable energy generation technologies”.

Between 2021 and 2023, the LCOE ($US/MWh) for Wind has increased from $US50 to $US75, while for Solar it has risen from $US41 to $US96.

Interestingly, in comparison to the IEA sensitivity analysis (shown in the graph above), the Lazard’s analysis of the sensitivity to interest rate increases shows that while the LCOE for Solar and Wind (onshore) would rise significantly as interest rates increase, the LCOE for Gas would remain above the renewable energies for all interest rates.

Offshore wind is the most disadvantaged of the renewables when interest rates rise.

Also, note that coal, gas peaking and Nuclear are no longer competitive at any interest rate (cost of capital), with Nuclear clearly never being a realistic option, despite a lot of progressives claiming its superiority.

There was an EU Observer article today on the same theme (October 2, 2023) – Is the ECB sabotaging Europe’s Green Deal?.

They pose the question:

With an increase of 4.5 percentage points in little over a year, the Frankfurt-based bank’s governing council has — wittingly or unwittingly — engaged in what is essentially an experiment: can the EU green transition succeed even when money is made so expensive?

They note that the higher interest rates have made “the transition vastly more expensive — which in turn could test the limits of what governments and companies are willing to pay to go green.”

But, of importance, and this is a point I made above, the ECB (nor any central bank) have no precise knowledge of what happens when they push up interest rates:

What doesn’t help is that the ECB modellers project such a wide range of real-world outcomes of their policies that even the most seasoned ECB watchers wonder if the bank has a clear idea of what the effects actually are.

It is all guess work and the variations in the real world from the guesses are often very large.

The article reports that a Dutch consulting company who has “estimated the transition cost for eight major climate technologies—including solar, wind, geothermal and e-boilers” has found that the costs “needed to reduce emissions, have ballooned by €17bn up to 2030, compared with the 2021 prices when interest rates were still below zero.”

The other problem is that:

… models they typically use for energy and climate-related decision-making ignore interest rate dynamics …

More work is needed, but the long term negative impacts of this period of unnecessary rate increases will certainly be significant.

For example, the article reports that:

… not a single investment in an offshore wind farm in Europe was made in 2022.

Interestingly, it then gets into the question of what fiscal policy could do:

Governments could offer developers better deals or increase subsidies. But relying on governments alone may be a risky bet as higher cost of debt is already leading to spending cuts. Higher costs could also fuel the resurgent right-wing backlash against green legislation, which is already underway in Europe.

Well that is a scenario that the Europeans have created for themselves and the Member States who use the common currency are certainly constrained in what they can do with fiscal policy given they use a foreign currency.

But for the rest of the countries around the world, fiscal policy is only limited by the real resources that can be brought into productive use, with the caveat that if resources need to be diverted from one use to another then policies other than spending are required.

That includes taxation changes – not to fund the spending but to free up the resources required so that they can be utilised in the public sector.

I will write more about the options facing governments in this regard soon.

Music – The Wind Cries Mary

Given the renewables theme today, I thought this great song would be appropriate.

The Wind Cries Mary – by – Jimi Hendrix – is one of my all-time favourite songs.

It came out in 1967 and was reportedly recorded at the tail end of a recording session in 20 minutes.

Masterful.

This is a live version released by the family of Jimi Hendrix and was recorded in Paris on October 9, 1967.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

What particularly annoys me about these energy production documents is that they always cost the projects in some numeraire. Usually US dollars.

That doesn’t help us choose the correct technologies. Both solar and wind are ending up with shorter than predicted lifespans and the production of them is producing a great deal of low level waste that isn’t being recycled effectively.

We need Energy returned on Energy invested, but it needs to include the fully circular waste management and the energy inputs from humans. I’ve not seen anything that takes this approach in a comprehensive manner – dust to dust.

Far too many of them still believe money is the scarce item – which is astonishing in 2023

The way I see renewables is that we are still in the “Ford T” phase of the techonology.

For billions of years that the planet Earth has been a “master” on sun energy harvesting.

Just look at plants and how they live on sun energy – some for thousands of years.

If plants can do it, so can we.

We need to invest on R&D to move forward from the “T” model of renewables.

That’s where the markets fails.

The private corporations are demanding derisking, meaning money for them to invest on the model “T” renewables: not on new technologies. No way!

And if you give what they want, they will run to the “casino” to gamble with it.

In the end, we will have spent the money and nothing will come out of it.