I have been thinking about the recent inflation trajectory in Japan in the light of…

RBA interest rate rises are inflationary and neoliberal privatisations have reinforced that

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists have argued from the outset that using interest rate rises to subdue inflationary pressures may in fact add to those pressures through their impact on business costs. Businesses with outstanding trade credit or overdrafts will use their market power to pass the higher borrowing costs on to consumers. In more recent times, we have seen other mechanisms through which central bank rate hikes actually add to inflation. Regular readers will know that I have been discussing how landlords have been passing on higher mortgage costs in tight rental markets, which then creates a vicious cycle – interest rates up, rental costs up, CPI up because rents are a significant component, inflation rises, interest rates rise. Repeat. The tight rental markets are in part, a consequence of the neoliberal austerity bias, which has seen governments seriously underinvest in social (low income) housing. In recent days, we have witnessed another conflation of neoliberalism and destructive policy insanity. Earlier this month, Australians received messages from the companies that provide them with electricity announcing that the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) had approved price rises of between 19.6 per cent and 24.9 per cent in various East coast states. How did that happen, especially as world coal prices are dropping rapidly and are now below the pre-pandemic levels? And how does the bias towards monetary policy exacerbate this situation?

As time passes, it becomes obvious that the various components that, in part, define the neoliberal era – deregulation and privatisation of the public utilities (water, electricity, telecommunications, etc), outsourcing of public services to the private sector, deregulation and collapse in oversight of industry regulation, particularly the concentrated sectors such as energy, banking etc, and the austerity bias which has seen public housing investment collapse, the prioritisation of monetary policy over fiscal policy – are problematic in the their own right and have failed to deliver on the promise.

But it goes further than that.

We are now seeing how these elements combine to create detrimental outcomes to citizens that were never envisaged.

Today, I want to talk about electricity prices, given the massive price hikes that have just been passed on to consumers in Australia.

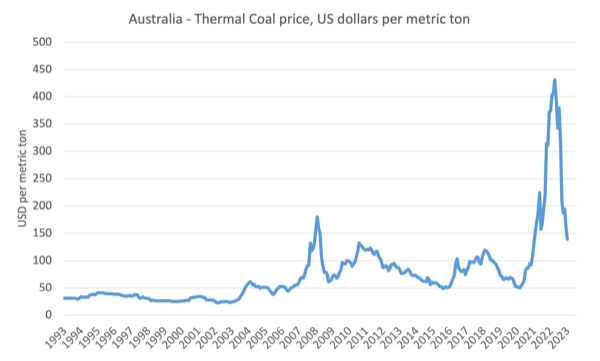

The following graph shows the prices (US dollar per metric ton) for Australian thermal coal (Newcastle/Port Kembla export ports) from June 1993 to May 2023.

I live some of the time within a short-distance of the largest coal export port in the World – Newcastle.

A massive amount of coal leaves the harbour through the heads each day in huge tankers, which are lined up all the way down the coast awaiting their turn to sail into the harbour and access the huge coal loaders that transit coal from further up the Hunter Valley.

It obviously presents a major issue for the region which will have to transition away from the dependence on coal as soon as possible.

But that is another topic.

The point of the graph is to show how far coal prices have fallen since their peak in September 2022 ($US430.81 per metric ton).

By the end of June, they were at $US139.42 and falling fast.

They are now below the pre-pandemic level.

Gas prices have followed a similar pattern in world supply markets.

Electricity prices and inflation

‘

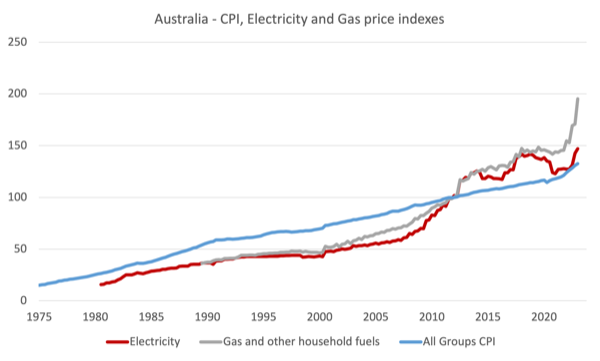

The next graph shows the movements in the All Groups CPI, and the Electricity and Gas components in index numbers from March-quarter 1975 to the March-quarter 2023.

It is clear that since the turn of the century energy prices have been accelerating more quickly than the general price level and this trend is extreme in the current period.

What is going on?

In terms of weights in the overall CPI, Electricity and Gas and other household fuels belong in the Housing Group, which comprises 23.24 per cent of the overall index.

Housing is also the most important component of the overall index.

Within that group, Electricity is weighted as 2.52 per cent and Gas and other household fuels accounts for 0.97 per cent of the total CPI.

So, important.

Shifts in electricity prices will thus drive significant movements in the CPI.

Which then prompt central bankers captured by the current NAIRU-ideology to increase interest rates.

So here is the problem.

The spike in coal prices as a result of the supply chaos associated with the Ukraine situation, weather disruptions in Australia and other factors pushed up the costs for energy providers.

Corporations in the highly concentrated energy market then passed those costs on in the form of the price hikes.

Which then pushed up the CPI.

Which then prompted the central bank to push up rates.

Which then led to higher business costs.

Which then were passed on to consumers.

Which then pushed up the CPI.

Which then prompted the central bank to push up rates.

And so it goes.

But in the Australian case the problem is compounded and driven by past government decisions.

Ask yourself why are energy prices rising so much when coal prices have fallen drastically and there has been no major wage rises in the sector?

Coal-fired power stations still dominate the generation scene in Australia despite the increasing use of renewables.

The Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water site – Electricity generation – note that:

Fossil fuels contributed 71% of total electricity generation in 2021, including coal (51%), gas (18%) and oil (2%). The share of coal in the electricity mix has continued to decline, in contrast to the beginning of the century when coal’s share was more than 80% of electricity generation.

Renewables contributed 29% of total electricity generation in 2021, specifically solar (12%), wind (10%) and hydro (6%). The share of renewable energy generation increased from 24% in 2020.

So despite a fast uptake of renewables, Coal is still dominant.

In the 1980s, the privatisation fever hit Australia and state governments sold off the public energy companies and split them into wholesale, poles and wires and retail, claiming that this would provide competition and better service at lower prices.

It was a myth.

To overcome the criticism that these were effectively natural monopolies and that the new firms would still have massive market power and be able to hold consumers to ransom because they supplied an essential service, the governments created a regulatory environment.

The Federal Australian Energy Regulator (AER) oversees this system and you can find detailed information at its – Energy industry regulation – site.

There are various components to the regulative structure.

But the problem started with the conditions of sale.

In most cases, to avoid an embarrassing sale, governments set conditions for the privatisations that were biased in favour of the purchaser.

The prices the assets were sold at were artificially low in many cases and the returns that the new operators could expect were insulated from the real world conditions that the sector was experiencing.

That is, governments provided guarantees on returns to the new operators to induce them into the market.

For example, in the state of NSW, there was a syndrome identified that became known as ‘gold plating’ of the poles and wires.

This was uncovered because NSW electricity consumers were hit with massive price rises.

It was revealed by the regulator that corporations who owned the wires and poles got around the regulative structure by ‘over investing’ (that is, ‘gold plating’) their networks and passing these costs on to final users.

After investigation the regulator tried to establish reasonable investment rates which were challenged by the operators, who then won a Federal court case on the issue – and continued to blithely rort the system.

It was obvious that there could be no competition in terms of poles and wires, because a wire has to be connected to a house and the corporation that owns that wire has a monopoly and can charge you what they like.

The privatisation arrangements though allowed the newly created firms to receive guaranteed rates of return on the investments they put into the network.

You can learn about the way the regulator treats returns in the – AER – Rate of Return Instrument – 24 February 2023.

Essentially, the regulator sets some benchmark return on capital invested that the energy companies can treat as a minimum and price to irrespective of the state of the market – given they are effective monopolies.

And the benchmark return rises if the central bank increases interest rates.

The AER notes that:

In summary, the approach and parameters we have chosen in the 2022 Instrument are largely the same as for the 2018 Instrument. However, the rate of return derived at this time from the 2022 Instrument is higher than the rate in December 2018. This is because underlying market interest rates have risen in recent years, rather than changes we have made to our approach.

However, when interest rates were low, the AER was concerned “about the sufficiency of our return on equity during the low interest rate period.”

So there is an asymmetry in the way the regulative system operates, which favours the operators.

But the point is this:

1. RBA hikes interest rates.

2. AER adjusts the allowable rate of return upwards.

3. Privatised corporations use their monopoly power to push up prices.

4. CPI accelerates given the large weight on electricity prices.

5. RBA hikes interest rates further.

The interest rate hikes designed to curb inflation add to inflation.

It gets worse.

The corporations are allowed to push up prices even further if demand stalls in the face of the interest rate hikes to ensure they gain a sufficient rate of return.

So just because the price of coal and gas have fallen, the privatised corporations can still push up prices based on the past investments.

That is the cost that the society is paying for the misguided privatisations.

Conclusion

In the past, these utilities were public services and their metrics were not based on private profit or return.

In that situation, we would not be caught up in this vicious cycle outlined above.

The fact that governments guaranteed returns to induce investment in the privatisation process has turned the electricity monopoly into an efficient profit-gouging mechanism that defies reality.

And it means that RBA rate hikes are inflationary themselves.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I believe that we could say that government abhors the void.

As soon as those elected for government follow the neoliberal tropes of “small government” (meaning that the government’s sole purpose is to protect the wealthy) and markets sanctity over all things, and stops governing, the void gets filled.

And so, government becomes a dummy act, as big business takes care of governing – in their favor!

Fully agree.

Bill,

I would like to know your opinion on the role speculation can have on inflation. During the pandemic the price of lumber skyrocketed over 400%. Was this pure supply and demand or did speculators play a role in such a large price increase? I know speculators can influence prices. There have been times when a hurricane is predicted in the Gulf of Mexico and the price of oil surges. Obviously the price had nothing to do with supply and demand because neither changed. So can speculation add to price increases or is speculation a zero sum game?

Thanks