I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Japan grows along with the hysteria

Today, the Cabinet Office in Tokyo issued the third-quarter Japanese national accounts data which showed that the economy has posted positive growth for the second consecutive quarter and is now motoring along at an annualised rate of 4.8 per cent (1.2 per cent in the September quarter). In the June quarter growth resumed at 0.7 per cent (2.8 per cent annualised) and so the recovery is getting stronger. Given they did not allow labour underutilisation of labour to rise very much (a large increase by Japanese standards but relatively small compared to countries such as the UK and the US, they should be able to absorb the jobless fairly quickly. But this will only strengthen the growing call for the government to cut back net spending. It is a case of denying what is staring you the face.

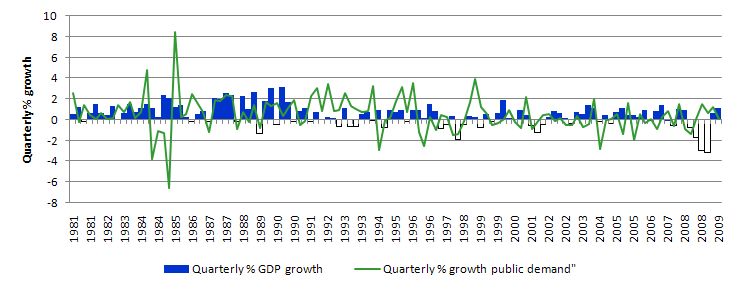

The following diagram constructed using the excellent national accounts data available from the Cabinet Office, provide a longer-term view of quarterly percentage movements in Japan’s GDP (blue blocks inverted when negative) and quarterly growth in public demand (green line). The graph gives you a good impression of how severe the current downturn is, even when compared to the difficult years the nation faced in the 1990s and recession in the early 1980s.

But the two increasing blue columns at the right-hand side of the graph show that the economy is showing signs of life underwritten by the very significant fiscal support that the Japanese government has provided.

The economy grew 1.2 percent in the three months ended September 30 and built on the 0.7 per cent growth in the June quarter. The 1.2 per cent was significantly higher than the investment bank economists had been predicting.

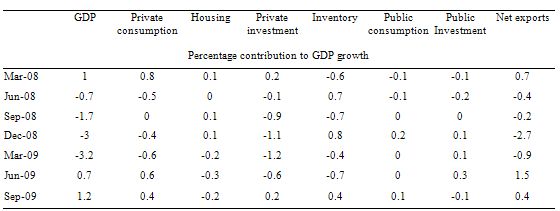

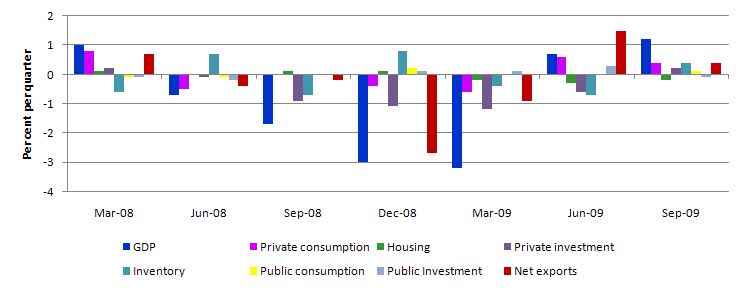

The following table shows the percentage contributions to quarterly real GDP growth since March 2008 (also shown in the next graph which is more eye-catching).

The Table shows that private consumption contributed 0.4 per cent to the GDP outcome again building on growth in the previous quarter. While investment in private residential housing continues to detract from GDP growth, private non-residential investment which had contracted for the last 5 quarters finally contributed positively to GDP growth in the September quarter.

You can also see that the inventory cycle may be turning with a 0.4 per cent contribution coming from firms building stocks after two quarters of stock run down. Part of the inventory run down is due to China’s strong public spending on construction which has aided Japanese building companies.

Finally, next exports continued to grow although less strongly than they did in the June quarter. Their contribution to the total growth outcome was on par with private consumption. Exports increased 6.4 percent in the Septmber quarter alone.

While it looks like the public sector has not contributed at all to GDP growth (public consumption was added 0.1 per cent while public investment subtracted 0.1 per cent from GDP growth), the public contribution has also working via private consumption and private investment. For example, households have been assisted by government spending to buy energy-efficient cars and household appliances.

For all the deficit-phobes, while Japan has resumed growth, it still has a long way to go to even get back to the level of output that it was producing before its 4 dramatic quarters of contraction began. During the downturn, Japan returned to its 2003 output levels.

Industrial production is still at about 80 per cent of where it was in early 2008. The capacity utilisation data also shows that around 33 per cent of Japan’s factories are not producing and there is little new demand for labour as yet.

This graph shows the percentage contributions to quarterly real GDP growth since March 2008 – that is, it the table data above.

So while the Japanese should be rejoicing, the local commentary from the financial markets is a worry. Bloomberg quotes a CS investment banker:

The problem is that you can’t expand fiscal spending forever because we’ve got this fiscal deficit to worry about … They’re concerned about the economy on the one hand, on the other they’re concerned about the deficit.

First, the opening statement is technically false. In a modern monetary system, you can expand the fiscal spending forever. Moreover, you can do it in an effective way if the growth in nominal net public spending is commensurate with: (a) the saving desires of the non-government sector (meaning private domestic in Japan); and (b) the growth in real productive capacity.

As long as the government maintains that sort of spending growth it can do so forever.

When I read some of the news feeds from Japan today (like the comments above) I was reminded of an article I read in 2005 from the Japanese daily Yomiuri Shimbun, which carried the title Fixing state’s finances new government’s main task (published sometime in early 2005 – I have lost the reference sorry). Here is an excerpt:

Japanese politicians being self-concerned and corrupted as they are, they have always postponed major reforms and left to their successors the task of looking at a way to limit expenses and pay back the already gigantic government’s debt …

What worries me is that the Japanese State is already near bankruptcy, and if the Japan Post is privatised as the PM wishes, it will only worsen the government’s solvability. It is years that observators wonder if the Japanese State will really go bankrupt. Every year, more debts accumulate, and more creditors are left with less hope of ever getting paid …

In fact, the debt is so bad that raising all taxes by 10% and cutting the government’s budget to avoid any further debts, would take almost 20 years to pay back the current debt, while putting enormous strain on the economy and individual wealth.

In other words, Japan has created money artificially during the past few decades, and this money has accumulated in the form of debts, both public and corporate.

Well first of all, government spending in fiat currency does come from no-where and the cumulative net spending is a record of the net wealth of the non-government sector in the currency of issue.

But moreover, despite the claims (in 2005) that the Japanese government was nearly bankrupt, nothing much happened did it?

And then, yesterday, on the eve of the release of the today’s very satisfying national accounts data, Reuters Japan carried a story about Japan’s bulging debt. The bankruptcy theme continues irrespective of the circumstances – this lot are like a stuck record.

After posing the imponderable “How much is too much?” the article continued:

When it comes to Japan’s bulging public debt, no one quite knows, but at about $75,640 for each of the country’s 127 million people, the burden is starting to worry both voters and investors. You can even see it climb in front of your eyes on an unofficial Website.

For those who can read Japanese, here is the “unofficial Website” mentioned. It is obvious someone has learned a modicum of javascript and is putting it to good use.

I interpret the so-called debt clock as the contribution of net government spending to private saving which I take to be a good thing for the government to be doing.

But in a Reuters Japan report last week we read that:

Japan’s fiscal woes are fast expanding as the new government eyes huge spending to meet campaign pledges, sending bond yields higher on worries about a glut of new debt.

Plunging tax revenues mean they now cover less than half of government spending, adding to the pressure on yields as investors fret about the growing gap in Japan, which already has the highest public debt among developed countries.

Rising yields could also lead to government pressure on the Bank of Japan to boost its buying of government bonds, pushing it back towards a policy of quantitative easing.

The only salient point to take from the article is that the automatic stabilisers are alive and well in Japan. Corporate tax receipts have fallen to 50 year lows and total tax revenue is at a 24-year low.

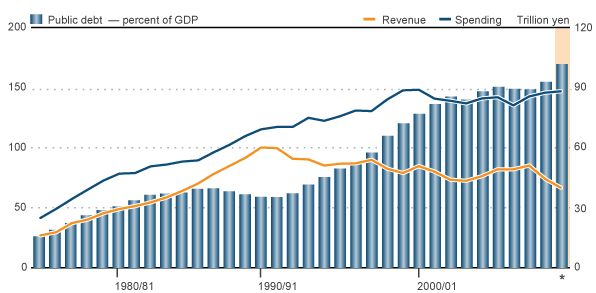

The following graph came from Reuters (and carried the heading “Japan’s fiscal pain” and the sub-heading “Rising spending and faltering tax revenues push up Japanese public debt”). I deleted the headings because when the Martian’s invade us in 150 years I don’t want too much evidence being left indicating how stupid we humans have become.

It is clear that tax revenue collapsed and so net spending had to rise. The growth in public spending has actually been more modest than would have been indicated by the contraction in private spending and net exports (see the negative red and purple bars in the second graph above).

But the financial press is agog with news that investors are worried, according to Reuters Japan, that the new government is “pledging to increase payouts to households with children and end expressway tolls but it has to cut other spending to make room for these policies”. In the same breath that particular commentary commentary then went on to say that:

Some economists worry a lull in spending between the end of old stimulus plans and the start of new policies could push Japan back into recession, in turn hurting tax revenues further and potentially demanding more government bond issuance.

This schizoid state of affairs is common in discussions across the Globe. The neo-liberals cannot mount a credible denial that the crisis has categorically demonstrated how effective fiscal policy has been. All these years of preaching introductory mainstream macroeconomics text book assertions that fiscal policy was a futile strategy to increase output and employment and would only generate inflation – well the way economies are responding to the fiscal intervention has fatally undermined these arguments. That they ever got traction is a sad statement about human intelligence levels.

But at the same time, the schizoids cannot let go of the other parts of the mantra – the crowding out and inflation stories. Both of which are as flawed as the rest of the nonsense but they can still scare the public by appealing to the “dark unknown future”. Bring a few kids into the story who are going to be grossly burdened in later life paying back all our debt (not!) and you have the makings of a real scare campaign.

The financial press in Japan is noting that the Japanese government is selling more debt in the wholesale markets because “retail investors are not keen on the low yields offered” (Source) and so yields are rising. But what they don’t tell the readers is that the Bank of Japan can easily purchase government debt at various maturities if it wants to contain the rise in yields.

This bit of information captures the idiocy of financial markets (Source):

The cost of insuring against default in Japanese government debt has risen to its highest since April. Five-year credit default swaps on Japanese sovereign debt have hit about 66 basis points from about 43 basis points two weeks ago, although they are still below a record of 130 set in February.

So the financial markets are somehow duping people into buying insurance for something that will never happen. It is like conning someone to buy insurance in case they live forever. The Japanese government has ample fiscal capacity to service its debt and attend to its other fiscal obligations. It alone issues the Yen.

If I was the Japanese government I would change the operations of fiscal policy and cease issuing public debt. The Bank of Japan can easily run its monetary operations without any debt transactions. And then imagine the screams that would come from the investment bankers who use the debt to price risk and also as a safe (risk-free) haven against uncertainty.

All this talk of deficit-phobia also resonates with Paul Krugman’s latest articles in the NYT. In one of two briefs yesterday, Paul Krugman’s Fiscal perspective said:

It’s truly amazing, and depressing, how completely deficit-phobia has swept the field in Washington. The economy remains in deeply dire straits … Yet the respectable thing, all of a sudden, is to claim that we can’t possibly afford to spend any more money on job creation …

I’d be a little more forgiving of the nonsense if all the people screaming about the deficit were sincere. And some are. But many, if not most, are perfectly happy to incur huge unfunded liabilities for the wars they want to fight, and/or to eliminate inheritance taxes for the heirs of multimillionaires. It’s only deficits incurred to help working Americans that get them all moralistic.

Anyway, the point is that the economy desperately needs more help – and yes, we can afford to provide it.

One would struggle to disagree with those sentiments. Even though Japan is now poking its GDP head above water the damage done to the real sector by the worst crisis since the Great Depression will take some quarters to repair. They haven’t even started to work on reforming the financial sector yet and unemployment is still at unacceptably high levels.

But when you read his second piece yesterday – It’s the stupidity economy you appreciate how far Krugman is from understanding modern monetary theory (MMT), which means he really doesn’t get the way the fiat monetary system works.

His first article is a case of stumbling on sense without really seeing the full picture and the full range of opportunities available to the sovereign government.

His opening gambit in the second article is fine – “bad ideas are acting as serious constraints on policy.” He then notes that with “interest rates up against the zero bound … conventional monetary policy isn’t sufficient.”

His options of how to deal with the ineffectiveness of monetary policy are, in his order of preference:

- First best: “… credibly commit to higher inflation, so as to reduce real interest rates”. So he is still thinking monetary policy is the best way to proceed.

- Second best: “… a really big fiscal expansion, sufficient to mostly close the output gap. The economic case for doing that is really clear. But Washington is caught up in deficit phobia, and there doesn’t seem to be any chance of getting a big enough push.”

- Third best: “… subsidizing jobs and promoting work-sharing.”

This ranking of policy options shows how far Krugman is from being in tune with modern monetary theory (MMT). He still believes that monetary policy is the preferred counter-stabilisation tool despite the evidence that it is relatively ineffective in this regard and relies on difficult to determine distributional assumptions about the spending propensities of creditors and debtors.

So in this case he wants to tweak monetary policy into action by creating inflation – to move the real interest rate below zero. It is not clear how he would provoke inflation anyway, given the recessed state of the US economy.

The only way I could see that happening at present would be for his second-best option to be deployed. And, by the time, inflation was becoming an issue and eroding the zero nominal interest rate into negative territory, the real economy would have recovered anyway. This ranking doesn’t make any sense to me.

His third best option should not be considered separate from the second. What is the most effective way to expand an economy using fiscal policy? If your aim is to promote employment growth then you have to engage in direct public sector job creation. Why bother with job sharing?

The fiscal capacity of the US government is such that it can generate a job for all those who currently are not able to get employment. If the government introduced a Job Guarantee and unconditionally offered a minimum wage (at a sensible level) to anyone who wanted a job, then the net spending increase would be smaller than if they tried to generate the same number of jobs by generalised expansion.

A generalised expansion stimulates private spending and output but requires the government to compete at market prices for the resources to be deployed. It also does not provide the government with a nominal inflation anchor.

Conversely, offering a minimum wage job to anyone who wants one, does not compete for resources at all unless people start quitting their lousy private job and prefer to work in a public Job Guarantee position. If that is the case, then welfare increases anyway because people’s preferences are being better attended too.

It is then up to the private employers who lose workers to the Job Guarantee to improve their working conditions and entice the workers back. Dynamic efficiencies would follow from such a process. But this sort of competition cannot be inflationary because the JG wage is fixed.

Strange times indeed

My penultimate observation today moves focus to the America’s. In the The New York Times today there is an article about a fairly significant reversal in financial flows. Typically, migrant workers in the US (some of them illegally so) send remittances back to their poor families in Mexico. The NTY reports that:

Unemployment has hit migrant communities in the United States so hard that a startling new phenomenon has been detected: instead of receiving remittances from relatives in the richest country on earth, some down-and-out Mexican families are scraping together what they can to support their unemployed loved ones in the United States.

How the elite line their pockets …

It also seems that universities are struggling with financial cutbacks. In this blog entry from my friend Michael Perelman the other day (November 9, 2009) I read that in a time when higher education in California is suffering from savage budget cuts, the bosses at the Californian State University system spent $US2 million of their funds hiring some consultants.

You might think this would be a sensible strategy to lobby for more funds for the system. You would be wrong. The story is that instead:

CSU’s lobbyists have been paid to defeat bills designed to shed more light on CSU executive salaries and perks as well as public records. In 2006, The Chronicle reported that millions of dollars in extra compensation was quietly handed out to campus presidents and other top executives as they left their posts.

Go to Michael’s blog for the full dirty story. One of these days I plan to write a book about Australian universities!

Conclusion

A good note to end on tonight.

Tomorrow evening I am giving a talk at Politics in the Pub, in Hamilton (suburb of Newcastle) on all my favourite topics – it will be a case of MMT^2.

Krugman seems to progress and retrogress a lot. I think he just needs to comprehend two things

1. The money to pay taxes and buy government debt comes from the government itself and fiscal sustainability is irrelevant.

2. Good lecture on reserve accounting where he is not carrying any cellphone and is far away from his computer.

Actually one more – that the Taylor rule game is seriously flawed.

Dear Ramanan

I agree.

By the way, someone sent me a comment you had made elsewhere about MMT where you noted that Levy Institute was the central location for the development of our work. That is not accurate. Randy works out of Levy and some other sometimes publish via there. But I have very little to with it nor does Warren.

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill,

Pardon my ignorance and presumption on this one since I do not have a mental map of the whole thing and my availability to literature is restricted to that website or maybe I haven’t searched enough. (I was just assuming that levy is a front end or virtual or a platform kind of thing like some inter-university centers in India).

Although I am rooting for our Japanese friends, I don’t see a lot motoring.

Nominal Japanese GDP (billions Y)

2008Q1 520,329.00

2008Q2 514,769.70

2008Q3 499,245.80

2008Q4 495,178.90

2009Q1 482,142.30

2009Q2 480,189.50

2009Q3 479,871.40

The last time GDP was so low was in Q1 1992. Part of the problem could be the insufficient policy response. On the other hand, it looks like the decline is bottoming out, but at almost 8% below peak. Nominal GDP is what counts, if all your growth is from deflation.

With prices falling at almost 5%/year, those Japanese bonds are looking great. Add in the currency appreciation and I have a hard time believing that households don’t want to buy them. Not sure why Japan is even issuing bonds; at 5%, holding cash is a great risk-free return, which I guess is part of the problem.

About the budget hysteria, I agree it is silly, but still I don’t like those diverging lines. They could have cancelled those debts back in 1990. Who needs to “save” 150% of GDP?

In the period 1940-1945, the U.S. government debt/GDP went from 50% to 120% to fight world war 2. Japan has exceeded those debt levels because of it’s inability to recognize and write off loan-losses.

Revised down from 4.8 to 1.3 (real) and -4.7% nominal SAAR.

http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/qe093-2/main1.pdf

I recommend that Bill move this from the pick’s to the pan’s category, as public demand dropped at a nominal rate of -6.3% SAAR, with a real quarterly rate of -0.4%. Why cut public demand in a period of rapid deflation?

Dear RSJ

Yes I saw it. They cannot feasibly cut public demand at present.

best wishes

bill