In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

The inflation backtracking from the central bankers and others is gathering pace

Remember all the hype from central bankers last year and earlier this year about how they had to get ‘ahead of the curve’ with their interest rate hikes just in case wage demands escalated and inflationary expectatinos became ‘unanchored’. Over the last 18 months, I consistently noted in various blog posts that this was all a ruse to create a smokescreen to justify the unjustifiable rate rises – given that the inflationary pressures were almost all coming from the supply side and those forces were temporary and abating. Well now, the mainstream, having pushed for the rate rises and got their way are now backtracking to maintain their credibility by claiming there are no wage-price dynamics in sight. It is a dystopia.

The rush of the interest rate hike lemmings

The pressures for the interest rate hikes were mounting even before the inflationary pressures emerged.

I have noted before that the cheer leaders for the hikes were the economists in investment banks or academic economists in the thrall of the financial markets.

These characters are regularly wheeled out on financial reports on TV and in the written media and held out as ‘expert commentators’.

The public hasn’t a clue and thinks a suit is a suit – someone to be listened to because obviously they know what they are on about.

Most listeners or readers fail to work out that these suits are, in fact, just boosters for their corporations – who gain more profits in an environment of increasing interest rates.

The central bankers, many of who have the revolving door aspiration to move into the private financial markets on spectacular salaries when their term in the public institutions ends, were under constant pressure from these boosters and eventually succumbed.

Only the Bank of Japan, among the large, advanced nations have resisted the pressures – to their credit.

And you will note that the mainstream press hardly ever refer to what is going on in Japan in this regard, given that it is diametrically opposed to the interest rate hike lot.

Of course, the central bankers had to create a smokescreen for the interest rate hikes.

They could hardly tell the public that they were succumbing to the gamblers and rewarding their short-selling bets with massive profits.

So, the New Keynesian framework is perfectly suited for this function.

After all, it says that:

1. Low unemployment will lead to nominal wage pressures that will instigate a wage-price spiral and so unemployment must be driven up until the inflation is quelled (the hoary old NAIRU story).

2. Price expectations will start accelerating and become self-fulfilling and drive the inflationary process independent of the state of the economy (the hoardy old ‘unachoring’ story).

So last year and into this year, statements from central bankers regularly claimed that they were moving fast on interest rates to ensure that wage pressures and/or inflationary expectations didn’t become problems.

Of course, there was no robust data evidence to support those fears as I have persistently pointed out.

But it is a case of say the same thing enough times in enough places and people start to think there is something there.

The other point is that central bankers have egos and only a limited set of tools with which they can demonstrate their ‘value’.

So after a period of low rates and a reemergence of fiscal dominance, people had to be asking – what do central bankers do to justify their huge salaries?

Pushing up interest rates allowed these characters to resume the centre of attention and massive their egos.

Well, now the rates are up the narrative is changing

In his blog post, which accompanied the release of the Spring IMF World Economic Outlook (April 11, 2023) – Global Economic Recovery Endures but the Road Is Getting Rocky – the IMF boss wrote:

Should we worry about the risk of an uncontrolled wage-price spiral? At this point, I remain unconvinced. Nominal wage gains continue to lag price increases, implying a decline in real wages. Somewhat paradoxically, this is happening while labor demand is very strong, with firms posting many vacancies, and while labor supply remains weak — many workers have not fully rejoined the labor force after the pandemic.

So, no wage-price spiral.

The other interesting aspect of this quote was his almost disbelief that there would not be such a spiral – “somewhat paradoxically”!

There is no paradox to an Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economist because what the mainstream interpret as being a labour market that is below the NAIRU – that is, beyond full employment – is in our eyes a market that continues to operate with excess supply – that is, not close to full employment.

They keep claiming Australia is beyond full employment but currently there are 9.7 per cent of willing and available workers either unemployed or underemployed.

Last week (April 20, 2023), the ECB released the minutes for the – Meeting of 15-16 March 2023 – where we read the following:

Although pipeline pressures were weakening, they remained substantial. Wage pressures had strengthened, supported by robust labour markets and employees aiming to recoup some of the purchasing power lost owing to high inflation. Moreover, many firms had been able to raise their profit margins in sectors faced with constrained supply and resurgent demand. The evolution of profits compared with that of wages suggested that wages had had only a limited influence on inflation over the past two years and that the increase in profits had been significantly more dynamic than that in wages. An important question for the forecasting of inflation was whether firms would continue with the same pricing strategy or would accept lower profit margins in the period ahead.

So:

1. Profit gouging – “raise their profit margins” … “increase in profits had been significantly more dynamic that that in wages”.

2. Wages growth not driving the inflationary pressures.

The point that is not appreciated by the economic commentariat is that rising nominal wages in an inflationary environment should not be

taken as an indicator of an emerging wage-spiral.

I have noted many times that it is hard to envisage a wage-price spiral becoming a driving force after an inflationary supply shock if real wages are being systematically cut, which is the situation all over the world at present.

See below for the IMF take on that point.

If you accept these findings then it becomes even harder to justify rising interest rates in the current environment.

I have explained previously that the logic of interest rate hikes is partly based on the need to move unemployment up to quell wage pressures.

If there are no wage pressures driving the inflation then that justification lapses and the intent to create unemployment is just malicious irresponsibility.

Relatedly, the prioritisation of monetary policy changes in an inflationary environment is based on assessments that spending in the real economy is outstripping the supply capacity, usually in a growth environment.

It is difficult to apply that logic to a situation where the supply capacity is artificially and temporarily constrained (by Covid etc) and is likely to restore to pre-pandemic levels soon enough.

But that point aside, central bank economists assemble all sorts of economic indicators to assess the state of the real economy – capacity utilisation rates, unemployment and underemployment rates, wage movements, etc.

Typically their interpretation of these indicators is coloured by the ideological biases in the lens they use.

But that also aside, economists know that movements in share markets are not particularly ‘connected’ to movements in the real economy.

The nature of financial speculation creates a disconnect it that regard.

So it is rather extraordinary that the ECB cites an observation that “broad stock indices had remained much more resilient than bank stocks, as the share prices of non-financial corporations had been affected only moderately” as an indicator of the stae of the euro macro economy.

This is the ultimate sop.

IMF finds wage-price spirals are rare and not likely in the current situation

On November 11, 2022, the IMF released a working paper – Wage-Price Spirals: What is the Historical Evidence? – which sought to determine the frequency of wage-price spirals in the past.

They were motivated by claims by the likes of Olivier Blanchard and others about:

… a potential wage-price spiral, with rising inflation and tight labor markets prompting workers to demand nominal wage increases that catch-up to or even exceed inflation.

Blanchard, Summers and their ilk get a disproportionate privilege in the public debate yet are rarely correct.

They have been monumentally wrong in the past and the errors have cost ordinary people jobs, incomes and worse.

Remember the fiasco concerning the IMF’s terrible mistakes in the crafting of the austerity program accompanying the Greek bailouts during the GFC, which elicited a rare ‘mea culpa’ from them when Blanchard was the chief economist.

With all the scaremongering about the likelihood of a wage-price spiral being unleashed, the researchers sought to see how often they have actually occurred in the past.

The conclusion: not often.

While the actual concept is rather vague, they found that:

1. “the great majority of the episodes identified in this manner are not followed by a sustained acceleration in wages and prices, with only a few exceptions. Instead, inflation and nominal wage growth tended to stabilize in the following quarters, leaving real wage growth broadly unchanged.”

2. On the rare occasions they do occur, Wage-price spiraling dynamics appear to have short lives”.

3. In terms of historical episodes similar to the “current macroeconomic situation” the inflation declined “while nominal wage growth increased thus allowing real wages to catch up … Acceleration of nominal wages should therefore not be seen as a sign that a sustained wage-price spiral is necessarily taking hold. Indeed, history indicates that nominal wages can accelerate while inflation recedes from its high levels.”

Expectations

On April 10, 2023, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York published their latest – Survey of Consumer Expectations (March 2023) – which shows that while there was a small uptick in short-term inflationary expectations in March, while at the 5-year horizon, they have “decreased slightly”.

The trend across the horizons is firmly downwards.

Here is the graph for the one- and three-year ahead inflation expectations series.

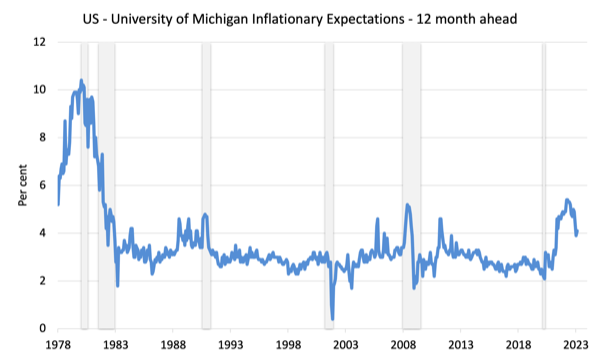

And what about the University of Michigan Inflation Expectation – data, which is shown in the following graph?

The grey bars are the NBER recession dates.

The Michigan data shows that that the one-year ahead expectation peaked at 5.4 per cent in April 2022 and has been in trend decline ever since.

This was the month that the Federal Reserve started hiking because it said it feared these expectations would rise.

Also compare the current situation with the experience of the late 1970s, just after the second OPEC oil price shock,

The decline back to the lower steady expected inflation in the 1979s took several years not months, as appears to be happening this time around as supply constraints ease.

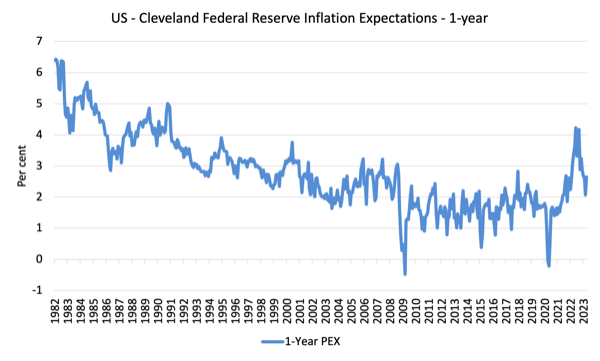

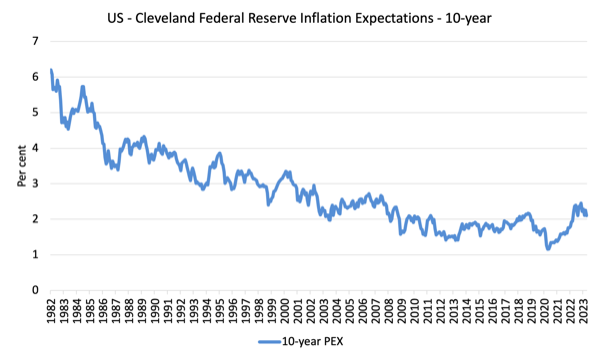

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland also provides an inflationary expectations series back to January 1982.

The most recent Cleveland Federal Reserve – Inflation Expectations – data, released April 12, 2023, shows that inflationary expectations across all time horizons are in decline.

1. The 1-year ahead expected inflation rate peaked at 4.23 per cent in June 2022 and is now at 2.64 per cent.

2. The 10-year expected inflation rate peaked at 2.4 per cent in June 2022 and is now at 2.10 per cent.

Here are graphs for the 1-year and 10-year expectations from the Cleveland model, respectively.

The data shows that inflationary expectations across all time horizons are in decline.

The question you have to ask is with all this information pointing pretty definitively to the absence of a wage-price spiral and/or an de-anchoring of price expectations, why have central bankers in continued to hike interest rates, especially when the most direct measure of the situation – the actual inflation rate – has been abating for months in most jurisdictions.

New Podcast – Episode 5, April 21, 2023

I have just released a new podcast episode – Episode 5 – where I invite listeners to get a pencil and paper out and do some arithmetic with me.

I assume the role of the government and the listener represents the non-government or citizens.

The exercise demonstrates that the imposition of a binding tax liability motivates the citizens to supply their labour to the government in return for its currency.

And, in doing so, the citizens solve the problem that the tax liability presents – that is, where do they get the currency from!

The corollary that arises is that it is the spending that creates the capacity to pay taxes rather than the fictional view that it is the taxes that fund the government spending.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

The expanders on the podcast ‘past episodes’ 4 and 5 aren’t working.

(The ‘div’ id for 4 and 5 are still set to ‘collapseThree’ and the button for 5 is still set to ‘collapseFour’ in the accordian).

Thanks Neil (at 2023/04/24 at 4:08 pm).

I have fixed the code now.

best wishes

bill

The western world is perfectly fine, while its elites weaken the States to their benefit.

If you privatize the State functions, you get decline and decline is not only economic, but also demographic.

The Japanese know very well about demographic decline – they have the world record.

It works like this: if the cost of living is too high, people will avoid having children: it’s cruel to bring children to a dystopian world. That’s all there is to it.

You can offset some of that decline with immigration, but only in economic terms and at the lower end of the labor spectrum.

If you need people to defend the Country, immigration won’t do you any good.

Japan can’t afford having a country full of elders.

If the land gets empty of people, someone else will come and take it.

That’s one of the biggest issues in Japan.

They have huge neighbours and they aren’t quite sure of their intentions.

Meanwhile, in the west, greed is not making plans for the future.

Greed intends to be the future.

That’s the direct cause of all wars: when two or more greeds collide, war happens.

Our biggest mistake was to think war was a thing of the past.

Remember the “history is dead” trope?

Well, it’s alive and kicking.

“The pressures for the interest rate hikes were mounting even before the inflationary pressures emerged.

I have noted before that the cheer leaders for the hikes were the economists in investment banks or academic economists in the thrall of the financial markets.”

Perhaps you’re being far too generous toward the basis for the intentions of the rate hike banshees, Professor.

The scenario you paint has been played out many times over the decades and on each occasion the top end of town benefits to the detriment of those that aren’t in that cohort. Don’t you think the puppeteers see what’s going on? Could now be the opportunity we’ve been waiting for to run another of those scams against the 99%? As the winds are blowing in the right direction (pandemic, war, OPEC+), we’ll just start the call and co-opt those theological neoclassical economists and their handmaidens in the MSM like we always do and give it another run, shall we? I reckon it’s murder, not manslaughter. Cui bono?

It’s just an up to date version of the snake oil salesman in the travelling medicine show that is neoclassical financialised economics.

Empirical, evidence based economics you say. Bah humbug. Mustn’t let any facts get between us bankers and etc. and a bucket of greedflation money. What’s actually going on in the real life and death world is a mere externality for those economists. Whatever they can get away with.

While there is a view extant (Mosler, Werner) to infer that raising interest rates causes/correlates with increasing inflation it’s looking like a positive feedback system where price gouging becomes a theme.

I believe the RBA governor gave the best answer to this rhetorical question.

It was something along the lines of our only ability to raise interest rates is to show the community we need to be the enforcer – if there is a better way of doing this, well, that is not up to us, we’re independent….

FT: If all you have is a hammer…

Fred Schilling: Yes, I also noted that “the intent to create unemployment is… irresponsibility.”