The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

The current inflationary period is not remotely like the 1970s

In the light of recent debates about whether we are back in the 1970s, where the only ostensible similarity is that inflation has accelerated over the last year or so, I dug into my data archives to remind myself of a few things. One of the problems with dealing with official data is that it gets revised from time to time and time series become discontinuous. So the labour market data for Australia tends to start in February 1978 when the Australian Bureau of Statistics moved to a monthly labour force survey. Researchers who desire to study historical data have to have been around a while and have saved their earlier data collections (such as me). But it is often impossible to match them with the newer publicly available data. You will see in what follows how that plays out. But, I was also interested to return to the past today after the ABS released their latest – Industrial Disputes, Australia – data (released March 9, 2023), which shows that disputes remain at record lows. So in what follows I show you how far removed the current situation is from what happened in the 1970s and this renders the narratives from our central bankers a pack of lies.

The history of industrial disputes

There are various ways in which one can analyse the manifestations of class warfare – number of disputes, number of working days lost, and the number of employees involved.

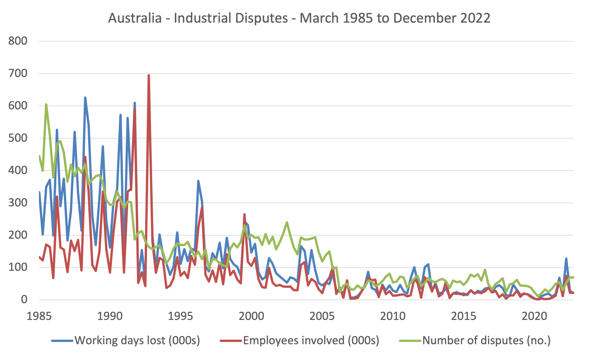

The current industrial disputes data series from the ABS start at the March-quarter 1985 and provide data on all three measures up until the December-quarter 2022.

The first graph shows the three series over that period and while there is a lot of noise in the data, the trends are clear.

This decline in industrial disputation has been huge and has been the result of deliberate public policy to weaken unions and make it easier for bosses to prosecute unions who engage in industrial action.

The decline marked the beginning of the period when government turned from being a mediator in the class struggle between labour and capital and became an agent for capital.

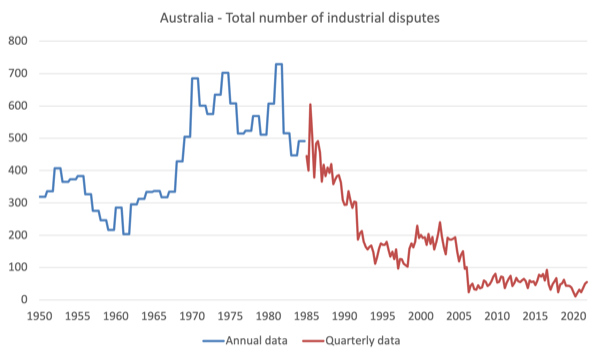

But we get an even better idea of how the industrial relations terrain has shifted by patching together older annual data from 1950 to 1984 to the current quarterly data shown in the previous graph.

The next graph shows the number of industrial disputes from 1950 to the December-quarter 2022 (the data was annual up to 1985 and then quarterly).

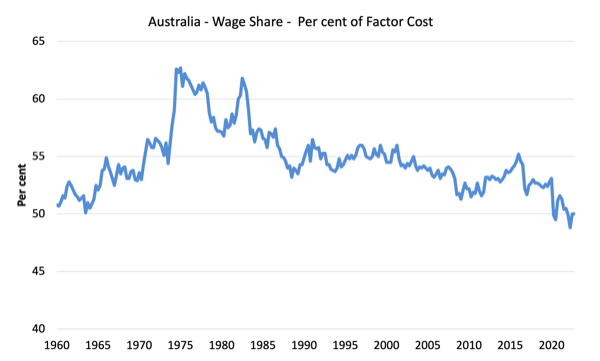

Further, we have consistent wage share data from the September-quarter 1959 to the December-quarter 2022, which is shown in the next graph.

The distribution of national income in terms of the wages share began the period (March-1985) at 56.6 per cent (after peaking at 62.7 per cent in the March-quarter 1975).

By the December-quarter 2022, the wage share had fallen to 50 per cent.

It is easy to see that when trade unions are able to effectively represent their members’ interests then the wage share is higher.

The problem is that trade union membership has fallen dramatically since the mid-1970s.

Historical – Trade Union Statistics, Australia, December 1975 – show that union membership was on the rise in that year:

Total membership increased by 52,100 (1.9 per cent) • Total membership increased by 52,100 (1.9 per cent) over 1974 to 2,814,000 … Between 1970 and 1975 male membership increased by 12 per cent and female membership by SO per by 12 per cent and female membership by SO per cent.

Scaling that by the size of the labour force, we learn that:

Trade union members at the end of 1975 represented 58 per cent of employed wage and salary earners. The 58 per cent of employed wage and salary earners. The percentage for malles was 63 per cent and for femalles percentage per 48 per cent.

Pretty heady stuff really.

Fast track into the present and the most recent ABS release of relevance – Trade Union Membership – tells a bleak story for workers:

– 12.5% of employees (1.4 million) were trade union members.

– Since 1992, the proportion of employees who were trade union members has fallen from 41% to 12.5%.

So in 1975, the coverage was 58 per cent.

By 1992, it has fallen to 41 per cent.

And by August 2022, it was down to 12.5 per cent.

We left the 1970s, a long time ago!

Phillips curve analysis

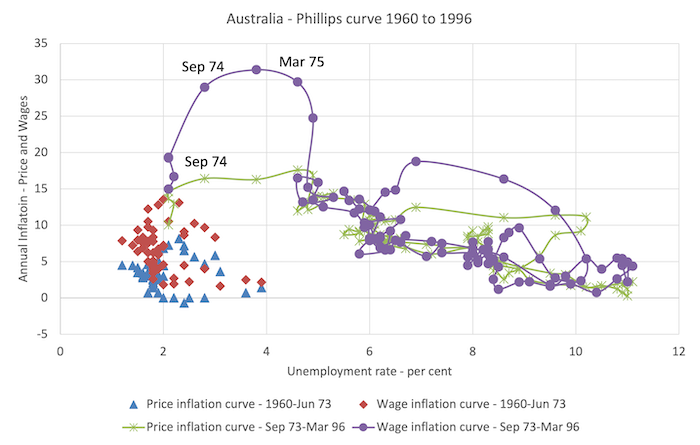

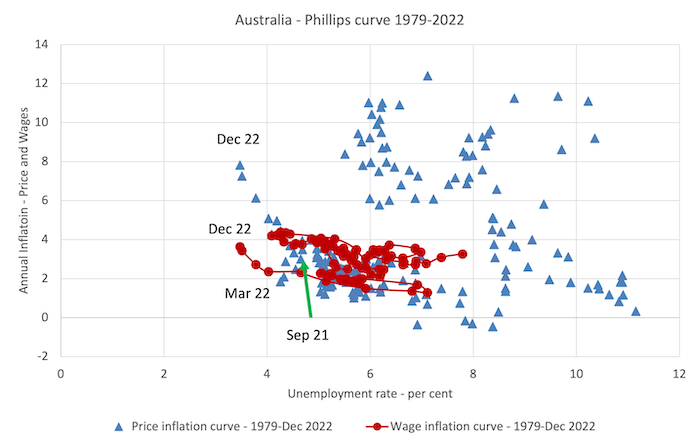

To map these labour force trends (disputes and trade union membership) into an inflation narrative, we need to construct some Phillips curves, which relate the unemployment rate (as a proxy for the strength of demand in the labour market) to measures of price or wage inflation.

The original Phillips curve first revealed in 1958 was in terms of the relationship between wage inflation and the unemployment rate.

In my PhD thesis, I showed that, in fact, the provenance of the relationship went back much earlier but it was the work of A.W. Phillips that attracted the attention.

In 1960, Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow converted the ‘wage Phillips curve’ into a price inflation curve by arguing that nominal wage pressure pushed up unit costs which were then passed on via mark-ups to the prices of final goods and services.

It is very hard getting a comparable wage data back in time as the statistician has altered the definitions etc creating several discontinuities.

So I dug into my archives and was able to construct this graph from the September-quarter 1960 to the March-quarter 1996.

The important point is that this data covers the turbulent period in the 1970s when the OPEC oil cartel pushed up oil prices significantly and the resulting imported oil prices set off a distributional struggle between workers and capital over who was going to take the real income loss as a result of the higher import prices.

I have constructed Phillips curves in both price and wage terms (annual growth on the vertical axis) with the official unemployment rate on the horizontal axis.

The two different ‘inflation’ measures are differentiated by the shape and colour of the markers.

I split the data into two sub-samples:

1. March-quarter 1960 to June-quarter 1973.

2. September-quarter 1973 to the March-quarter 1996.

The split in the sample is when the industrial mayhem really took off.

The lines between the observations in the second sub-sample help you to understand the trajectory of the wage and price inflation measures around the time of the split.

There were very strong nominal wage demands in 1974 as workers defended their real wages.

The wages growth was also pushed along in 1974 as a result of a large public sector wage realignment under the then Labor government.

The point is that the real wage resistance pushed up real unit costs (which is measured by the wage share) significantly and corporations then used their market price setting power to defend their profit margins.

So the initial supply shock from the imported oil price hikes soon became an endemic structural inflation in the domestic economy pushed along by the distributional struggle between wages and profits.

The shift to the right in the relationship over the course of 1974, was characterised by the Monetarists as evidence that the natural rate of unemployment had risen.

The reality was that it really marked the start of the obsession against fiscal deficits and at that time, governments abandoned their Post-WW2 commitment to full employment and pursued fiscal contraction designed to hold the unemployment rate at elevated levels while purging trade unions of their capacity to get wage increases for their members.

Fast track to the current period.

The next graph shows the data from the March-quarter 1979 to the December-quarter 2022.

The difference between the episodes – 1970s and now – is very stark.

Wages growth has been very subdued over the last few years and the current inflation rate is accelerating well above it, leading to systematic and significant real wage cuts.

Those cuts are increasing in size.

The data shows that there is no wage-price spiral and as inflation was accelerating in response to the supply factors wages growth was barely moving.

There is also strong evidence that corporations are profit gouging ‘because they can’ – doing so by using the smokescreen of rising costs except the price acceleration is well ahead of the cost acceleration.

Last week, I cancelled a relationship with a firm in the construction industry who I wanted to do some work for me because they came back with a revised contract with something like 150 per cent increases in the quote ‘because of rising costs’. No costs have risen that much. They were shown the door.

Video – the Current Inflation – Causes and Remedies

As part of the on-going MMTed edX MOOC that we are running which provides free education for those wanting to learn Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), I created a new video to update the material from the last time we ran this course.

All the other video material is only available to participants in the course but I decided to make this one generally available.

I had to do it very quickly yesterday (no scripts) and was not in my usual filming location so I did a quick and dirty Zoom recording (with any meeting participants) which gets the job done but the quality is less than perfect in terms of how it deals with syncing the video with the audio.

But at any rate it gets the message across.

Conclusion

The point of today’s blog post is that this inflationary episode is not at all like what the globe experienced in the 1970s.

The problem is that central bankers keep referring to wage-price spirals and expectations to justify their decisions to hike rates.

The reality is that those justifications are just smokescreens and there is no justification for what is being done under the aegis of monetary policy.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I understand how a scholar like Yourself needs to remain halfway between left and right.

And the truth is that macro-economics shouldn’t have to be ideologicaly biased.

The trouble is that right-wingers do it all the time, and so the discussion is always lopsided, if we try to remain neutral.

Progressives always end up leaning left, even if they prefer not to.

That’s exactly what the 2022/23 inflation bout is all about.

Raising interest rates is a right-wing move to shift wealth from the 99% to the 1%, as a tool to offset, ex-ante, the losses of the upcoming crisis – maybe the mother of all GFCs.

The script they are following is exactly the same they followed back in 2007/08: interest rates kept going up, until the Lehman Brothers bursted to pieces.

I remember having my mortgage interest rate going up to about 5%, just before the burst.

And we are getting very close to that already.

Euribor rates (6 months) only got positive (0.009%) in the 6 of june of 2022.

Not a year as gone by and we are already with 3.418%.

They are in a hurry.

MMT values money through a “use-value” lens. Central banks (and neoliberalism generally) value money through an “exchange-value” lens. MMT struggles to obtain public acceptance because the public, based on personal (micro) economic experience, sees money through the exchange-value lens (and really does not understand the use-value concept).

The RBA is in a club where noone wants to go against the instructions and lead taken by Big Brother USA https://theconversation.com/central-banks-hunt-in-packs-heres-why-ours-ought-to-be-wary-181465 except, as Bill continues to point out, the Bank of Japan. The BOJ is operating on an MMT understanding for the benefit of the majority of its citizens and not for the 1%. The BOJ stands apart from the crowd but it’s as if it doesn’t exist from the perspective of incurious and ignorant orthodox economists, the politicians in their thrall and their common propagandists.

The RBA kept raising rates to follow the US and will continue to do so until many/enough people and small businesses are broken and they have inflicted a recession. It’s all working as it was designed to https://theconversation.com/underlying-australias-inflation-problem-is-a-historic-shift-of-income-from-workers-to-corporate-profits-200700 – setting up a bankrupt stock sale for those with capital.

Icing on the cake: “RBA Governor Phil Lowe obtained a half-price home loan – from the Reserve Bank to purchase his 5-bedroom property in Sydney’s eastern suburbs in 1997. There are 11 current/former RBA employees still benefiting from the scheme.”

We can see the capture of central banks and governments by big capital as the divide and conquer controls are maintained on the pricing of labour while there’s zero control on the prices that labour has to pay to survive in our “free market” society of financialised economics.

Yes, John, which is why MMTers should never talk about public SPENDING by currency-sovereign governments but only about public INVESTMENT. Has not the cause of MMT suffered by continuing to talk in outmoded mainstream language about the startlingly new reality seen through its radical, revolutionary lens? When new wine is put into old wine skins, a prophet once observed, the skins burst. I join his call for new skins for new wine. Investment, not spending, and the list goes on.

This comment is not directly relevant to this post, but thought it would be best to make it here rather than a post 12 years old

In response to a question, I asked at the CBA AGM, CEO Matt Comyn stated:

“We also do create deposits in the system, we expand money supply when we lend money”

You state:

“Loans create deposits”

“MMT notes that bank loans create deposits not the other way around”

You also say:

“Private banks still need to “fund” their loan book. Banks have various sources of funds available to them including the discount window offered by the central bank which I explained above. The sources will vary in “cost”. The bank is clearly trying to get access to funds which are cheaper than the rate they charge for their loans.”

To my simplistic mind this is a contradiction, do Banks expand money supply when they lend, or do they need to fully fund their loan book from various sources, or is there some middle ground I have missed?

“do Banks expand money supply when they lend, or do they need to fully fund their loan book from various sources”

Yes. they fund their loan books from various sources. Those sources include deposits, and loans create deposits. When the private banking system is running copacetically, most of the withdrawals from one bank get redeposited in another bank (or even the same bank.) Withdrawals of money lent by a bank are mostly netted-out by deposits of money borrowed from a different bank. Random differences can be handled in the overnight credit market.

Wolf Richter’s Wolf Street blog today has a non-copacetic story. Big American banks are in big American trouble. Dying crypto customers are withdrawing the money they thought they had, but somehow the money is winding up in Treasury Bills, and not going to regenerate deposits, so the spending that funds those withdrawals is leaving the private banking system. Interesting times.

The NSW Labor Party is planning to remove the public sector wage cap if it wins the election on March 25, Will this drive a wages push in the NSW public sector which will flow into the private sector and start the wages-prices spiral?

PS: A reminder from the 70s.

“..the chief economic failure of my government resulted from the wage explosion of 1974. In part, our failure was a failure of communication, our failure to persuade the trade union movement to accept the central concept of Labor’s program….Our expenditure programs clearly increased the ‘social wage’, the standard of living which workers enjoy through the services which the community provides.”

(Gough Whitlam)

Michael Sanderson: According to the RBA : Deposit and money growth are typically driven by new lending by the banking sector. Lending creates deposits as the funds made available to a borrower find their way into a deposit somewhere in the banking system, either as a deposit in the borrower’s account, or in another account when the borrower uses those funds to make a purchase.

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2020/aug/box-d-recent-growth-in-the-money-supply-and-deposits.html

The “middle ground” I think you may have missed is the securitisation process used to fund the loans post the banks finding credit worthy borrowers.