I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Being careful not to swear in Dubai

At present I am in transit in Dubai waiting to fly home to Sydney after a week or more away in Central Asia. I am definitely being careful to avoid any public swearing, which means I am not reading any economics or business reports in public spaces. With the worry that I might swear out aloud and get stuck here, I judiciously completed all my reading in the privacy (assumed) of my hotel room at the airport. Lucky. Imagine what would have happened if I had been reading this article – David Cameron’s tonic to snap us out of recession – out on the concourse?

The facts behind the article is that the UK recorded its sixth successive quarter of negative GDP growth (the longest sequence in its available data history) and was a slap in the face to the business economists who were all saying last week that the recession in Britain was over. The poor result has allegedly given the conservatives a political filip although last week’s BBC program where the seriously lunatic BNP leader appeared seems to have given the latter the political boost for last week. I was going to write about the appearance of the BNP on the national television program but decided against it. My position is clear: the lunatic fringe do us a justice to appear on national media and face that level of scrutiny. I also do not believe in any form of censorship. As an aside, in terms of whether I like the BNPs political position or not is irrelevant to whether they should be heard. I would ban the conservatives too if repugnance was the criteria.

Anyway, the mainstream conservative reaction to last week’s national accounts disaster in the UK has been swift and predictable. A quick assessment is that they do not understand a single thing about the monetary system and are not qualified to lead that nation – not that I think Labour undertands anything much.

The article written by the Tory leader and Prime Ministerial aspirant David Cameron starts off reasonably:

Friday’s growth figures were deeply disappointing. A 0.4% fall in our national income may not sound much, but it adds up to £6 billion over a year. And its effects will be painfully felt in more bankruptcies, redundancies and repossessions. Gordon Brown, the man who said he had abolished boom and bust, has given us the deepest and longest recession since records began.

The economic interpretations are sound whereas the political statement in the last sentence is just that. An extended recession is incredibly costly and has a long tail – anaemic recoveries, lost productive capacity, and entrenched and debilitating long-term unemployment. The plight of 16-24 year olds in Britain is particularly accentuated – this will have negative implications for the next generation.

Cameron then claims that while “France, Germany and Japan started growing six months ago – and are getting stronger and stronger” the UK is being “badly left behind”. He atttributes this to:

… the economic mistakes of the past. For example, the government’s Vat cut added billions of pounds to what was one of the biggest budget deficits in the developed world, making the debt crisis even worse.

This is where he begins to reveal he has no idea of the role that a government plays in a modern monetary system. The British government budget deficits have risen in part because of the automatic stabilisers and in part due to discretionary policy decisions taken by the Government. The scale of the downturn in Britain has been so significant – in part, because of its larger exposure to the financial mayhem that generated the crisis – that the rise in deficit was inevitable and necessary. The discretionary additions to the deficit, while perhaps not to my taste (for example, I prefer direct public job sector to VAT cuts) demonstrated leadership rather than vandalism.

The fact that the British Government like most voluntarily choose to issue public debt – pound-for-pound – to match its net spending (deficit) is stupid and unneccessary but has no bearing on the failure of the economy to recover. The debt issuance is just draining the reserve adds generated by the deficits. So what? It is also adding an income stream to the holders of the debt and therefore providing a risk-free source of return to financial markets which have been reeling from poor (and corrupt) investments in an array of high risk (which they couldn’t price in anyway) derivative assets.

I would not issue debt at all but the fact that the Government is stupid and has chosen to do so is certainly not contributing to a “debt crisis” – see this blog for my views on debt issuance

The debt crisis that Britain faces remains in the private sector and results from years of neo-liberal inspired policies which failed to regulate the financial markets in any coherent and effective manner – all in the pursuit of the mantra that self-regulation was best. That is the legacy that British Labour should be judged. Like “Labour” parties around the World (definitely in Australia) – and I include the current US democratic party in this “team” – the British Labour party embraced neo-liberalism with panache – thinking it gave them economic credibility.

However, they were just seeking “validation” from the wrong assessors. The idea that the business community and its host of business economist mouthpieces – who are paraded out daily in the media telling us that deregulation, budget surpluses and all the rest of the poisonous suite – is in our best interests and constitutes the epitomy of fiscal excellence is the problem. Why we ever fell prey to that lobby is a question that needs to be researched further and a coherent answer provided.

So I would be attacking that failure in policy rather than the UK government’s current stimulus response if I was commenting on why the UK is in such bad shape. But then, of-course, the Tory’s would have been worse. Under Thatcher they set up the pre-conditions for the current demise of the economy.

Cameron then says:

The other reason Britain’s economy is still stuck in recession and falling behind those of other countries is that Labour has no serious plan for our economic future. The countries that are recovering strongly are all doing three things: getting their banks to supply credit to businesses; giving investors confidence; and implementing a proper plan for growth. In all these areas, the government is failing to act. It is astonishing to think that, 12 months after the bank rescue, lending to businesses is still falling. It is shocking that the government has still not come forward with a credible plan to get the deficit under control. If we fail to get a grip on public spending, investor confidence will fall, interest rates will rise and there will be fewer jobs. It is almost unbelievable that at a time when we face not just a debt crisis but a jobs crisis too, with unemployment heading for 3m, the government is planning to bring in an extra tax on jobs by raising National Insurance contributions.

The failure of the banks to lend at present is because there are not enough credit worthy customers willing to take a risk and invest. The response of the government via the Bank of England in this respect has been a farce. They thought that lending was reserve constrained – which is a reflection of their neo-liberal leanings and mindless devotion to textbook myths that have no application in the monetary system they oversee. So they embarked on a massive quantitative easing campaign and surprise surprise – not much happened. I explain why this comes as no surprise to a modern monetary theorist in this blog – Quantitative easing 101.

So in terms of monetary policy the British government failed to understand what the real problem was and is. Banks can always lend and do not require reserves to do so. That hasn’t been the problem. Adding reserves was never going to alter the fundamental lack of confidence in the outlook of the economy.

The cry for a credible plan to “get the deficit under control” is another neo-liberal ploy which is resonating all around the World. SBS radio (national Australian broadcaster) woke me up this morning in Dubai asking me for an interview for a program they are compiling on this issue. During the telephone interview, I told them that these cries represent a real danger to the recovery prospects for our economies. At present, with private saving rising (to repair balance sheets rendered precarious by the private debt binge), there is a need to support aggregate spending. When private spending begins to recover, the deficits will fall anyway via the rising tax revenue and declining welfare payments.

At that point, the governments will have to consider how much spending growth is required to match the real capacity of the economy and a vital signal will be the rate of labour underutilisation. While the conservatives are calling for cutbacks even while unemployment continues to rise, the prudent and responsible action will require governments to keep running deficits for the indefinite future (unless their countries experience large net export contributions).

The deficits are also putting downward pressure on interest rates contrary to what the Tory leader says. He is just mimicking the mainstream textbook nonsense about crowding out. In a modern monetary system, where savings are a function of income, the central bank sets the interest rate (and conditions the term structure), and inflation is not a foreseeable issue there is no application of that textbook reasoning.

Business confidence is about whether it can sell things into the product markets. It will begin investing when it thinks there are durable recovery prospects. The deficits are rquired to underwrite spending and stop if falling off a cliff.

Anyway, the Tory leader proposes a three-point plan which would be a disaster for the current British economy if implemented:

Proposal One:

… we need change in the banking system. A lack of credit, coupled with big margins between the interest rates at which the banks can borrow and the rates at which they lend, is still sapping demand from our economy. Fixing this should be our priority. For nearly a year now we have been calling for a national loan guarantee scheme. This would underwrite lending from banks to businesses – guaranteeing billions of new loans and helping new enterprises to start and existing ones to survive.

The lack of credit is due to the lack of customers who are credit worthy. A national loan guarantee scheme might be useful but then you would also have to seriously alter the way banks have been operating. This blog indicates the scale of reform that is needed – . I doubt the conservatives would be smart enough to implement these reforms.

Proposal Two:

… we need change in public spending. Unlike Labour, we have acknowledged the scale of the debt crisis and been frank with the British people about the difficult choices we will have to make. That is why we have started to set out a plan for reducing public spending, including a one-year pay freeze for all but the 1m lowest-paid public sector workers, in order to help protect jobs.

As above. It would be a total disaster for the British economy to start reducing net public spending at this stage. A sustainable long-term growth path, given that Britain is not about to become a large net exporter will be for the private sector to wean themselves of the debt train which in turn will require national budget deficits indefinitely. Get used to it. Any attempts to push back to surpluses would be self-defeating and prolong the damage already evident in Britain.

A reasonable dialogue should, however, be focused on abandoning the voluntary policy to issue public debt to match public net spending. Then the “debt monkey” would disappear soon enough. Irrelevant as it is.

Proposal Three:

… we need change in our attitude to the economy. At our party conference, we announced our plan to get Britain working. It is the most radical departure in economic policy in this country for a generation – a plan to unleash investment and enterprise so we create more wealth and jobs … Getting Britain working is also about getting people ready for work. This is where some of our most radical reforms come in. We will bust open the state monopoly on education. That will increase competition, raise standards and make sure our children get the education they need to succeed. Our plans for technical schools in our 12 biggest cities and 100,000 new apprenticeships mean we will also develop the engineering and technological skills of the future. And we will radically reform the welfare system so the unemployed get the tailored support they need to get back into work.

Notice “getting people ready for work” not generating jobs is the policy mantra. Full employability rather than full employment. Churning unemployed people through relentless training programs divorced from a paid-work context has been the neo-liberal approach for years and intensified after the release of the 1994 OECD Jobs Study. It has been a failed strategy – and will continue to fail.

Further, a focus on welfare reform that he mentions is all geared to a construction that a person is unempoyed because they lack skills or have the wrong incentive structures (in part because of failed government policies). Mass unemployment arises from a lack of jobs. You can bully and train and starve the unemployed “until the cows come home” but if there are not enough jobs then this strategy will always fail. You might be interested in this blog – Training does not equal jobs! which considers these issues in more detail.

Anyway, I am glad I don’t live there given this lot is likely to win the next national election.

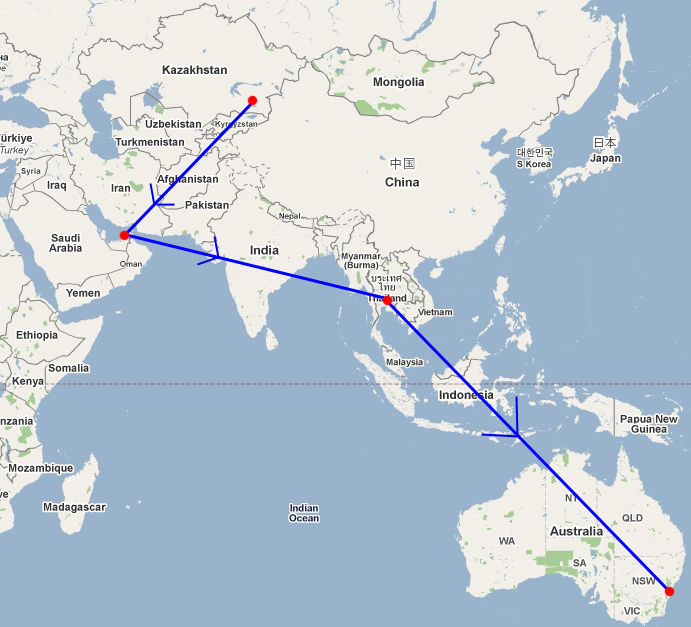

So with all that done, I can now safely poke my head out into public and head for my flight to Sydney via Bangkok – safe in the knowledge that I will avoid any spontaneous public swearing outbreaks in Dubai.

Next blog:

I will be back with a new blog on Tueday afternoon sometime. Probably late. Unless I run out of things to write about.

I’m glad you are feeling better! I have a usability suggestion: In most websites, clicking on the title banner will bring you back home. In your website, it is just an image — I keep clicking out of habit. It can’t be too hard to insert an a href = “..” there, and the address would of course be static. Instead you have a little “home” text link on the right. It’s too small and in the wrong place.

Other than that, Kudos.

I listended to this speech of Cameron’s on News Radio the other morning. I wondered what you would make of it (although I had a fair idea). But surely there must be some genuine economic reason beyond ideology to issue debt pound for pound to the deficit?

Dear RSJ

Thanks for your suggestion. It has been implemented.

best wishes

bill

Dear Michael

There is definitely more to it than ideology. Debt is issued to drain the reserves added by the deficits so that the central bank can hit its overnight targets and preclude the interbank market competition that would arise if there were excess overnight reserves. Of-course, the same end could be reached if they just paid the target rate on excess reserves. Therein lies the ideological choice.

best wishes

bill

Hi Bill

I actually do believe that unemployment for many is as a result of the wrong incentive structures as a result of govt. policy.

I remember hearing PM Brown make a big deal about the number of unfilled vacancies advertised a few months ago.

The unemployed may lack skills in the sense of skills employers demand but no longer invest in. Again, this is where govt. have issued numerous policies in the past. As you said most of it is on the lines of training places and apprenticeships for 16-19’s.

The problem in the uk is that training and further educaiton in the UK is disproportionately focused on 16-19 year olds. Where’s the funding and choice in FE and training for those above 19.

As for quantitative easing, isn’t QE basically more of the same guaranteed income for instituional investors and banks. The argument goes that banks have been able to rebuild their balance sheets with QE and the extra liquidity the central bank has pumped into the market has seen the rebound in the stock market.

Hi Bill

I have to admit I’m uncomfortable with the idea of using interest payment on reserves to control the funds rate. Doesn’t this just transfer the risk free return from would-be buyers of government debt to the commercial banks? I don’t see that this is in any way superior to the current state of affairs. Or would you just fix the interest rate at zero?

Dear PS

I would just fix the short-term rate at zero and then manage the economy including specific asset price booms with fiscal policy. That would free some smart minds in our central banks up to go back to university and re-train as cancer or HIV researchers, or something useful.

best wishes

bill

I agree with your remarks about Cameron. I posted some critical remarks about him on one of my blogs 24 hours ago: http://ralphanomics.blogspot.com/2009/10/obama-and-david-cameron-are-clueless.html

Johann Hari had an article in the Independent in the UK a few months ago entitled “Why are we silent as Cameron preaches voodoo economics” : http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/commentators/johann-hari/johann-hari-why-are-we-silent-as-cameron-preaches-voodoo-economics-1691107.html

Personally I think this article was an insult to Negros who engage in witchcraft type activities in Haiti.

Hi Bill,

Your IE Bug fixing worked the other day, but this time, it seems to be the opposite! Probably you were too worried about how the page looks in IE this time and there is a bug in how it looks in other browsers. If I click the banner it brings me back to the same page instead of the main page. In IE, however it doesn’t happen but it doesn’t show the “fingers” icon if I move the mouse around the banner.

Thanks for the change, Bill. Very satisfying to click on the header.

re: the zero rate

Here are some concerns, in the spirit of debate, as you say 🙂

I haven’t seen a rationale as to why a zero rate is welfare enhancing. Low rates are associated to with high asset prices, volatile asset prices, increasing income inequality, and greater returns to capital rather than labor. For example, the dividend payments and interest payments/GDP are higher when rates are lower, as the increase in borrowing far offsets the smaller return per dollar borrowed. It also means that capital is expensive, relative to the underlying cash flows, which doesn’t seem like such a good policy to have, as it will distort the accuracy of investment price signals.

Moreover, how would you address asset price booms (and busts) with fiscal policy? When rates are low, the discounting mechanism means that returns far in the future are more important than when rates are high, and these are the returns we know nothing about. So how to tackle this fundamental uncertainty and correctly price assets via fiscal policy? It seems that you are requiring much more volatility here, and ultimately arbitrary credit-rationing.

I also think that, in the case of the U.S., dumping 7 trillion worth of deposits with banks would play hell with things like duration matching and capital requirements. Trying to think that one through a bit. It seems to me that having a zero rate kills interest rates as a tool to manage credit growth, and leaves you only with bureaucrats poring through loan books, trying to predict what the tail of an unknown distribution is, or whether a bank should extend a loan to a self-employed person, etc. I think you will need to nationalize all the banks in that environment.

Same problem with solely relying on taxation to drain — it is a very blunt tool; a tax code change requires an act of Congress and takes a year before you collect the revenue. Moreover, people can change their behavior to avoid paying some of the tax, so that the total receipts are uncertain. Finally, constant adjustment of tax rates means that households would experience more income uncertainty, which encourages more savings and artificially limits consumption.

All in all, it seems that you are 1) putting the economy in a more unstable situation, due to the increased asset price instability and valuation problems in a low discount environment, and that 2 this risk is amplified by a 7 Trillion currency pool that can quickly transform into credit growth. At the same time, you are tying the hands of government to mitigate these risks by forcing them to use slow, poorly understood and more ineffective tools. I would like to see a rationale that tax code changes or capital requirement would be better at inflation fighting than the Fed funds rate management.

This is not to say that we should stick to the current constraints on draining currency that we issue, but there is a big leap from not requiring matching bond sales to banning bond sales entirely. In the same way, I think you need both fiscal and interest rate management policy. I’m trying to be open minded here, so any arguments are welcome.

RSJ . . . a few responses:

1. Asset price bubbles are almost never caused by low interest rates. Look at the US in the 1980s, for just one counter example where there was a bubble with relatively high rates (or the 1990s, for that matter, with just a bit lower rates). Or consider Japan over the past decade with a zero rate policy . . . any bubbles there? The common denominator for asset price bubbles is always anticipated capital gain. Raising interest rates a few percent or even 10% won’t stop an asset price bubble, and as Minsky demonstrated, actually makes things worse in the end.

2. Don’t confuse a policy of setting the overnight, default-risk-free rate at zero with a policy of setting all interest rates at zero. Bill’s advocating the former, but by no means the latter. Regarding all those reserves, a few very simple things can be done to offset, such as the Treasury offering bills at a fixed spread from the overnight rate, thereby leaving the quantity of balances circulating voluntary (Warren Mosler has other proposals on his website). Banks also aren’t required to hold capital against reserve balances.

3. The only effective approach to stopping asset-price bubbles is good regulation of the quantity of credit. Again, evidence everywhere shows that interest rates don’t do this effectively. And a further part of the problem is that “markets” price risk countercyclically, which is the opposite of what’s desired. So, again, financial regulation is in order. Bill and colleauges at CFEPS and the Levy Institute have published a good deal of research on better approaches to financial system regulation from a Minskyan perspective.

4. Appropriately designed fiscal policy (see many of the posts to this blog for more details on how this might be defined) is a far better tool for managing macroeconomic cycles than changing the overnight interest rate, which often has quite perverse cyclical effects.

5. Note that issues you’ve raised regarding asset-price bubbles have been discussed in blogs and comments here (https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=5240) and here (https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=5098).

Best,

Scott

Hi Scott,

I appreciate the response.

1) This is of course path-dependent with Japan. There is a lot of evidence that low rates increase asset volatility and they certainly do lead to asset bubbles in areas such as housing and equities. There have always been booms and busts in these areas, but the magnitude of these swings is very highly correlated with interest rates, as you would expect — people borrow as much as they can afford. This is why houses had much lower price to rent and price to income multiples in the 1980s then in the 1990s and again the price to income was much higher in the 2000s. If you read the data, for example the survey on consumer finances, you find that debt service payments increased only slightly, meaning that consumers were able drive up prices. There is a lot of evidence that people are payment-constrained when it comes to lending. Of course, once you are already burdened with debt, zombified, and in a deflation, then no in that Japan-style stagnation and revulsion you will not generate another asset bubble. That is little comfort, though. I am also not claiming that low rates are the only cause of such bubbles. Discovery of Oil in Norway and many other income shocks can cause bubbles.

And you haven’t made the case of why a zero rate is welfare enhancing — it is associated with increasing inequality, higher levels of indebtedness, and greater asset price volatility. What is the counteracting “plus” for a zero rate, and what is the calculus that determines that these benefits outweigh the costs? I am not asking for an algorithm so much as a rationale that a zero rate is a goal that we should strive for. Why is “zero” not a less arbitrary number than 3? What advantage does zero have over 3?

2) Yes, we are only talking about the call money rate, and of course bank capital is required to back loans, not deposits, but bank capital will not be hard to come by in a world flooded with deposits in which the overnight cash is free.

A proposal to float bonds — a “fixed spread” is irrelevant, the market will price the coupon — is good; it means that we are no longer limiting ourselves to a no bond-issuance policy. In that case, is there any policy guidance on when you drain via taxes versus via bond issuance?

For the other points, I am questioning the ability and competency of the government to effectively assess whether loans will not perform, and I am skeptical that it is possible to have a tax/spend policy flexible and rapid enough to manage inflation and prevent asset bubbles.

If there are specific proposals (e.g. ban further lending when the Debt to GDP ratio is above 1, issue an emergency gas tax whenever CPI grows by more than 5%) that can be evaluated as to their feasibility, then I’m eager to look at them. Merely stating “fiscal policy will do a better job” is not enough — you need to lay out the rules, algorithms, and the enforcement mechanisms, and then argue that both are robust. I have 700 years of financial crises in which everyone was always stunned when the assets turned out to be worth a fraction of their agreed upon value, and I have 200 years of banks running around regulators. I have 100 years of governments being too paralyzed to deal with inflation and deflation. I have a history of Nixon incomes policies failing spectacularly. Just declaring “fiscal policy is more effective” is not good enough to give the banks access to cash at zero overnight rates.

I will poke around in the blog for specific mechanisms to identify/prevent asset bubbles and to control inflation, but I haven’t found these in the links you mentioned. I haven’t read all the comments, though. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t expect 100% answers to every problem, but some specific and assessable arguments that would justify the zero rate policy.

Dear RSJ,

I don’t buy that a low overnight rate has ever been the operative factor in a modern asset-price bubble. With housing and equities, again, it’s expected capital gain. If you were investing in Amazon in the late 1990s, would you have severly adjusted your valuation if the Fed had raised rates a few percent? 5 percent? 10 percent? With the housing bubble, again, failure to assess credit risk, offering loans that were essentially call options on price appreciation, etc., were the operative factors, not the level of the overnight rate.

Low rates are associated with income inequality because rates are usually low during recessions when unemployment is high . . . no surprise there. Again, the overnight rate is not the operative factor . . . the unemployment rate is far more important.

Apologies for answering your question with another question, but I approach the welfare enhancing issue differently . . . why should anyone earn a positive return overnight for taking no risk? Where’s the welfare in that? Also, any macro or distributional issues can be dealt with via fiscal policy (again, sorry for making a point I realize you already don’t agree with, but with time constraints I can’t do any better than to point you toward Bill’s many posts on fiscal policy and the job guarantee). Again, some of this was covered in comments on a blog I linked to above.

Regarding “higher levels of indebtedness,” for whom? And regardless, a past correlation need not be repeated (path dependency, as you noted). Certainly that could be true, but it need not be . . . and again for the private sector isn’t true in Japan and presently in the US (as the household sector deleverages, at least a bit).

Banks make loans (or at least should) based on creditworthiness of borrowers. How many deposits or reserve balances they have shouldn’t affect that decision, and certainly doesn’t affect their ability to make the loan in either direction (capital can constrain lending, not deposits or reserves, in other words).

I wasn’t suggesting “floating” bonds . . . offering them at a fixed price relative to the overnight rate. Reserves left circulating represent a choice to hold those rather than bonds.

Proposals: again, see Bill’s post on the job guarantee and the vast literature on this at CofFEE, CFEPS, and Levy sites; see all the research at Levy on re-regulating the financial system; see Warren Mosler’s proposals for fiscal, monetary, and regulatory policies; see Bill Black’s proposals for financial regulation at the KC blog. There’s not much point or time for repeating all of that here.

And, yes, even with the “perfect” policy framework, there will be enormous difficulties in implementing and getting political buy-in; banks will always try to get around regulations, which Minsky always reminded us; Nixon’s policies were fundamentally flawed from the beginning . . . none of that provides any evidence that adjusting the overnight rate works better.

Best,

Scott

This might be of interest, too.

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=4656

Hi Scott,

I will return to this discussion later, but will just answer this question before taking off:

“Apologies for answering your question with another question, but I approach the welfare enhancing issue differently . . . why should anyone earn a positive return overnight for taking no risk?”

I am very suspicious of this type of reasoning. We have a responsibility to make economic rules that maximize welfare given the workings of a complex and interconnected system. It is better to leave the value adjustments for the end-result, and set the rules that maximize the end results, rather than setting the rules from a value-judgment perspective and then just assuming that the end result is optimal. This was one of Keynes’ great insights — to approach the problem of economics as a technical one.

Low call money rates have historically not led to lower inequality, and this is not because of recessions. If you look at BEA data and sum personal interest receipts + dividend payments/GDP, you will see no correlation between that return on financial assets and the call money rate. Therefore if your “end goal” is to limit rentier profits, lower rates is not the way to go about it. Another data point that things get a bit complicated and you cannot deduce the policy prescriptions from moral reasoning alone. Moreover, you could also have high call money rates, and then recapture rentier profits with taxes, as you point out, so again there is no “moral” reason to have an interest of rate of 3 rather than 0 or 1, unless you can show that it is part of a policy that makes long term sustainable consumption.

In this case, you can also ask why we should let the most irresponsible member of the economy have access to free money, or why we should not require that speculative activities meet some return threshold prior to being carried out. You could also argue that people are systematically optimistic in estimating returns, and that therefore requiring a safety margin of estimated risk + constant is more welfare enhancing, as it will lead to more prudent investments of limited capital. It then makes sense that this constant should be flexible — it could well be zero sometimes — but that it should change if other macro economic variables change, such as capacity utilization or unit labor costs, since these are indicators that there isn’t a large slack of “real” capital, and that therefore the marginal cost of marshaling more should be higher than if we were in a situation of overcapacity. To me that seems much more likely to lead to optimal allocation of investment capital, and if someone earning a return bothers you, then you can of course tax them as you point out.

Anyways, I must go, but thanks for the discussion.

Hi RSJ,

A few opinion on some of the questions you have asked. High interest rates are bad for employment. This is because firms borrow from banks to make investments in fixed capital, earn from sales, keep some amount for depreciation, accumulate inventories, pay interests on loans and the residual is the wage bill. They also do other things such as raise cash through equities, corporate bonds and firms have huge assets – financial as well as in real estate. Wage numbers are far from being the result of a game called supply-demand and are the residuals. Higher interest expenses tend to put downward pressure on the wage bill and hence employment. On the government bonds side of things, high rates imply higher interest payments. In my opinion, from a fair division viewpoint, the government bond holders do not really ‘deserve’ the payments since unlike a corporate bond holder, he/she didn’t ‘help’ the government which is not constrained like a firm or a household. Government interest payments are ‘free money’. Zero interest rates means that governments can spend more because they do not have to make interest payments. This is because even though they are not constrained, there is some sort of limit if one takes price stability into account.

I think I know where you may feel uncomfortable. Ratios such as P/E are comparable to 1/r, where r denotes the typical interest rates we see. Investors use 1/r and price in a bit of risk to do an analysis of pricing of stocks/markets. I will come back to this. let me think carefully and get back to you.

Hi RSJ,

The point is absolutely NOT to end investor profits. I wrote a paper on this that made precisely the same points you did . . . investor returns would not necessarily be hurt by a 0 overnight rate. You’ve thus made my point for me . . . it’s only the overnight rate that’s at zero . . . and why should anyone make more than this for default-free, risk-free investing? (And you didn’t provide any answer as to why they should, by the way . . . given how prevalent the opposing view is, I would expect it would be easy for proponents to find a response.) Other rates are free to be set in markets. Investors are free to make whatever returns they can . . . and these could very well be higher or at least more stable given a far less volatile overnight rate (bank profits would be more stable as rates on liabilities and some assets would be more stable, bond investors would have less worry about capital loss from interest rates rising, equity investor returns from capital gain and dividend yield are more due to the state of the economy in the aggregate . . . though there might be a one time adjustment in P/E). I agree with the further points made by Ramanan regarding economic costs of higher and more flexible overnight rates (and from a Minskyan perspective, the costs of adjusting the overnight rate are very high in terms of financial stability). And, again, you could look at the post Bill did regarding specifically this policy proposal or the comments Warren has responded to on his site.

Best,

Scott

Hi Scott,

“You’ve thus made my point for me . . . it’s only the overnight rate that’s at zero . . . and why should anyone make more than this for default-free, risk-free investing? (And you didn’t provide any answer as to why they should, by the way . . ”

This is a fundamental misunderstanding. Let’s disaggregate the financial private sector from the the non-financial sector e.g. “banks” and “investors”. In no sense does FedFunds represent a 0 duration risk-free rate available to investors, therefore the premise of the question is false.

From 1974-2009, here are the average of monthly real rates available to the private sector in various instruments.

MZM Own Rate (0 maturity): -1.9%

1 Year Treasury: 1.8%

3 Year Treasury: 2.3%

10 YR Treasury: 2.9%

AAA Moody’s: 3.9%

BAA Moody’s: 5.0%

The real effective FedFunds rate is at 1.7%, about the same rate as a 1 YR treasury, but it has bounced from below the 3 month T-Bill to more than the long bond (in 1980).

The risk free rate for investors has yielded -1.9%. That is a spread of over 3.8% between the 0 duration risk free rate available to investors and the 0-duration risk free rate available to banks.

The mechanism by which the FedFunds affects the credit market is the signaling of FBOG announcements, together with the effect of an increase in bank cost of capital to loan rates, which of course are important for the economy. But this increase is filtered via the asset:capital ratio. I.e. for a 12:1 ratio, a 6% increase in the bank cost of capital corresponds to a 0.5% increase in the required return of bank assets. In no way does FedFund correspond to a 0 duration rate that an investor can obtain. They must part with liquidity and/or incur default risk in order to obtain the FedFund rate, unless that rate is zero.

Investors make money from bearing risk and parting with liquidity. They always have the option of purchasing equity, and obtaining the GDP growth rate as a return instead of committing their money to bonds. But if they do this, e.g. purchase a broad basket of equities, then although they will 0 default risk, they will need to make a long-term capital commitment in order to realize this return. Historically, a 60 year hold is required to be guaranteed of the GDP growth rate return. Therefore those investors who want to commit their funds for a shorter period of time will buy a broad basket of bonds. In this case, they still will experience 0 default risk, but will pay less in liquidity and obtain a lower return as a result. So the key determinant is always liquidity, or the duration of commitment. It is never default risk, if the investor is not risk-seeking (e.g. trying cherry pick an investment).

However, investors will reliably earn a positive return for a 0 duration commitment if the FedFunds rate is zero. In this case, because MZM accounts must pay something, as banks do value deposits, investors will earn a “free” positive return without giving up liquidity. Therefore there is absolutely no reason to keep the FedFunds rate at zero unless you can argue that social welfare maximizing benefits of cheap yet more volatile credit for house purchases outweighs the social costs free real returns without a liquidity sacrifice.

Moving on to banks. Here there is no “moral” issue of banks charging each other for excess reserves (I hope). You could argue that these costs are passed onto borrowers, but again only filtered via the capital multiple.

But herein lies the rub: the liquidity preference can spike, causing the bank’s cost of capital to increase. So there is reason for making the FedFunds rate variable, so that what is passed onto borrowers is held constant. This is because rate spikes are much more destructive than a non-zero, yet constant rate, which I suspect is welfare-enhancing if not too high. Keynes did not advocate for a zero rate of interest, but that the rate be *lowered* in times of crisis when liquidity preference spikes.

Why do I suspect that a higher rate is welfare enhancing? When discussing banks, it’s critical to keep in mind that bank lending is primarily a real estate phenomenon. You will end up with all the wrong conclusions unless this is at the forefront of your thinking. The Schumpeterian hero that takes out a loan in order to innovate and expand capacity does appear in history, but is a statistical discrepancy in the flow of funds. In the U.S. there are now 14.5 Trillion in mortgage loans (of which only 17% are commercial and the rest residential), 4 Trillion in trade credit (which is often government funded), 2.4 Trillion in consumer credit, and only 500 billion in non-mortgage loans outstanding to non-financial businesses. Here I am looking at the balance sheets of commercial banks from the latest Fed Funds, so this excludes MBS on the books of agencies as well as “shadow” entities. I am also ignoring loans to financial entities.

80% of productive investment is funded by retained earnings. The remainder is funded by commercial paper and corporate bonds, which move with the the 3 month and 10 YR rates as set by the private sector rather than with the FedFunds rate as set by the government (recall that the FedFunds has bounced around from less than the 3 month T-Bill to more than the long bond).

The key thing to notice here is that the vast majority of loans are made on assets that do not produce a stream of cash-flows at all, and there is deep ambiguity about how to “value” a house. They are also price-inelastic but payment dependent, and so there is real harm in lowering the rate unless it is to offset a spike in liquidity costs, as it makes non-productive assets more expensive relative to incomes and increases indebtedness. Moreover there is a clear need to limit cost of capital spikes. Therefore the null hypothesis is to have a positive rate that adjusts with demand for the thing borrowed.

I enjoy this conversation.

P.S.

I can no longer click to go “home” by clicking on the header! Impotent clicks result.

Hi RSJ,

I refer you to a paper by Eric Tymoigne at the levy website Fisher’s Theory of Interest Rates and the Notion of “Real”- A Critique

The paper quotes Keynes as saying The role of real variables should be left for historical comparison, not for current economic analysis. The only reason real rates seem to appear everywhere is because of the <obsession of central banks with them. If one sets the interest rates to zero, there is no concept of real. We would still use them to look things like real GDP growth etc but not from a financial viewpoint.

“Real” is a very vague concept. An investor faces two choices – invest in financial assets or buy commodities (and speculate!).

Example CPI was 220 a year back and climbed to 230. The “consensus” is that it will hit 235 in the (toward the end of the) next 365 days. The central bank can still set the 1 year rate to 1%. One has two choices: invest in the 1yr or buy commodities and speculate (plus equities etc.) There is no arbitrage – the second option is not guaranteed to pay off more. I believe you have misinterpreted Scott’s and Bill’s point.

And indeed the “…alternative economic thinking” school of thought is the only one to speak and analyze retained earnings. Very rarely do mainstream economists speak of this. Also, I think you may have compared stocks and flows in your comment. The numbers seem to be different from the latest Z1, page 9, table D.3. Households’ total outstanding debt is $13.7T, Business $11.1T, Domestic Financial Sector is $16.5T. Undistributed profits (table F.7) for the whole of 2008 was $480.7B. The important point is that credit (and sales, earnings, equity issue etc.) not only finances fixed capital and inventories but also wages. There are a few things that do not come out so well from the Flow of Funds, even though its an excellent thing. For example, sales can lead to repayment of loans and this wont show up in the flow of funds which will talk of ‘net’. So one has to look at it dynamically. The fact that credit is the backbone of Economics is illustrated so well in the work of people at Levy and CofFEE. Economists (following the work of Keynes) talk of multipliers a lot but their calculation is one-period and the dynamical effects come out more prominently if one does a stock-flow consistent calculation.

Dear RJS

I have now a better solution to your header request. It should work fine now.

best wishes

bill

Hi Ramanan,

If you object to using real rates, then you can of course add CPI back. The spreads wont change, and the argument is about the spreads. Namely that the FedFunds rate does not correspond to a risk-free rate that investors receive, and that the relationship between the FedFunds rate and investor rates is complex. The FedFunds affects investor rates (such as 1 Yr Treasuries) to the degree that it influences the return prospects for the underlying economy, together with investor sentiment. A 0% Fed Funds rate or a 5% Fed Funds rate can and does co-exist with both low and high yields. It is false to claim that lowering the Fed Funds rate will, in and of itself, cause rates that investors receive to be lower — this all depends on what happens to the underlying economy. If a low rate causes inflation, then yields will rise. If it causes deflation, then yields will fall. These effects are path dependent and not well understood.

Re FoF, you are citing total credit market debt levels, whereas I was citing levels of *loans*. The FedFunds rate is not directly relevant to the rates paid by bonds, but it is relevant to the rates charged for loans. It’s important to understand the difference between the two:

When a bank makes a loan, it creates both the asset and the liability at the same time. Therefore no one is giving anything up when a loan is made — there is no inherent opportunity cost. We have a 700 year history of crises, with huge inflations and deflations of credit. Because of this, government backs banks and in return enforces opportunity costs administratively. The effect of a (simplistic) 12:1 capital requirement is to force $12 of loans to “cost” $1 of capital. This amount is completely arbitrary — we could require it to “cost” $2 of capital. The effect of a 5% FedFunds rate is to ensure that the $1 of capital earns a return of at least 5%, or that banks earn at least 0.4% spread on each loan made. This is again arbitrary, but serves as a safety cushion that forces banks to charge just a little more than their futile efforts at quantifying risk would lead them to charge — even assuming zero moral hazard and perfect oversight. This spread also allows for a cushion, so that if liquidity preference spikes up by 5%, we can lower the FedFunds rate by an equal amount, and keep customer costs constant.

But in no way does the ability of government to enforce opportunity costs on *loans* correspond to an ability to set interest rates on the bonds. When buying a bond, an investor is parting with purchasing power and is facing real opportunity costs not controlled by the government. No one is required to participate in the bond markets at all, and wealth does not flow from these markets. Wealth comes from owning capital, and investors always have the option of directly purchasing capital and earning the GDP growth rate as a return, provided that they are willing to commit to holding the capital for a long enough time period that the variability in returns washes out to the GDP growth rate.

Suppose that the GDP growth rate is a (nominal) 6% in the U.S. Someone offering a bond at 4% or 2% needs to offer compensation in exchange for this reduced yield. That compensation is a shorter hold period. The spread between the long term GDP growth rate and the bond rates of varying maturities is then determined by the willingness of the public to accept a lower yield in exchange for the enhanced liquidity. Government cannot control this willingness directly. You will never be able to drive the nominal 1 year rate to zero, unless nominal GDP growth expectations are low and liquidity preference is high. Although government might be able to engineer such a situation, it would not be welfare enhancing.

P.S.

None of this has anything to do with support for a Jobs program, an emphasis on fiscal policy, not requiring that deficit spending be matched 1-1 with bond sales, or having the bankers turn to studying cures for cancer. You could just as well tell them to leave the FedFunds rate at such a level so that bank costs of capital is 5% and let them cure cancer. More and more I favor nationalizing the banks and turning them into government utilities, with government salaries, at which point the FedFunds rate becomes irrelevant, as they would not need to go to the capital markets for anything. In that case, you can replace this rate by a fixed premium that banks charge customers in addition to historical loan default data. These are all very interesting questions.

P.P.S.

Bill — yes the header link works now. Thanks!

Hi RSJ,

Statements such as “.. investors want to be compensated for purchasing power” exist in the first place because the Central Banks and the Treasurys have designed the system as such. A 5 year bond has a yield of say 5% because investors think of the possible inflation in the next 5 years and the central bank moves Fed Funds Target Rate according to inflation data. The Fed can set any rate it wants. In principle it can set the whole yield curve if it makes changes in the way bonds are auctioned. It can set the data such higher the inflation, lower the rates. For example it can set the overnight rates to 25bps permanently by paying interest on reserves and offer 1y zero coupons at $99 – take it or leave it. If nobody takes it, its not a failure of the Treasury – investors just missed an opportunity.

Coming to banks, as you have pointed out, they create loans and deposits out of thin air. In a zero overnight rate environment, they can set it any rate they want depending on competition amongst themselves and the credit quality of the customer. Surely will not depend on inflation expectations. The rates set by banks depends on the target profit. Corporate bonds (all sorts of corporate debt issuance) bought by households through mutual funds will compete with loans directly from the banks. If the investor wants any protection against purchasing power, and if the demand is low, corporates can just walk to the banks. Coming back to banks the fed funds’ level does have an effect because if the deposits are moved to another bank, the loan giving bank may find itself owing the loan amount in the overnight market. Deposits created out of loans by the latter bank could move to the first bank and there are all sorts of things happening out there and the banking system on the whole may have to borrow from the Fed through the discount window.

The reason that yields go high when investors demand protection on purchasing power is that the government debt market itself is designed that way. The corporate yield has some spread over this because of chances of default and liquidity risks. Yes, corporate bond yields and government bond yield move in opposite directions sometimes but if the yield level of government bonds is less, this will surely make the corporate bonds go down.

Regarding the flow of funds, I realized what you were saying just after I posted my comment. But as I have mentioned, its an alternative to taking loans from banks. A loan level of $x per Q does not mean $x/4 per M because firms’ sales will be used to pay off the loan. The fact that firms have prenegotiated lines of credit is very essential.

Theres is another reason for low rates. There is an idea in PKE literature on pricing of goods. Its called Markup pricing – Firms decide pricing of goods they want to sell based on wage costs, interest costs etc. In markup pricing theory higher interest rates lead to higher costs for goods because the outflow of cash in interests. Of course wages themselves depend on interests so some simultaneous equations have to be solved. Marc Lavoie and Wynne Godley’s text Monetary Economics is an excellent text for such things. There are some things in the book about which I don’t agree with wholeheartedly but an amazing book nonetheless.

$99 – take it or leave it. If nobody takes it, its not a failure of the Treasury – investors just missed an opportunity.

In your analysis, you ignore equity entirely. Capital is owned by someone — by investors! Fixed debt intermediates between investors of varying liquidity preferences, but no one needs to use these intermediaries if the risk bearing services they provide are too expensive in relation to investor’s own preferences.

No one is required to rent when they can own, and vice versa. In fact, the vast majority of assets are owned outright; the fixed income instruments are about 15-20% of household assets, and (federal) government debt is about 20% of the fixed income market — so only 4% of household assets are held as government bonds. Globally, equity markets are twice the value of fixed payment markets, and a large majority of (global) capital is not sold on the equity markets at all, but is held as real estate and other forms of private equity. 80% of investment capital is quite happy earning the GDP growth rate as a long term return, and 16% of the remainder is a bit skiddish, and so favors fixed payments. Of that 16%, 4% is so skiddish that they give up an even greater yield in order to purchase government bonds. Do not confuse the availability of the instruments from the willingness of investors to hold them. The latter is innate, and depends on expectations and preferences. This is why loanable funds is a myth. By supplying more money to the markets, government will not necessarily drive yields down; it may drive yields up. These effects are complex.

The Fed cannot set even a single interest rate, let alone the whole yield curve, as that curve reflects the relative preferences of investors. No one is forced to rent when buying is cheaper. No one is forced to buy when renting is cheaper. The calculation of being willing to earn a smaller return in return for a shorter time commitment is a trade-off made by each person, and the results of those calculations form the yield curve. The far end of the curve is the GDP growth rate. None of this can be controlled by the government directly.

Surely [they] will not depend on inflation expectations

Surely they will. The FedFunds rate is a surplus reserve loan rate, but does not capitalize banks. Banks have *both* cash-management needs as well as capitalization requirements. The FedFunds rate only affects the former, and not the latter, because you cannot capitalize banks with overnight loans. You must go to the private sector capital markets to obtain bank capital. Again, bank equity is owned by someone, and returns of bank capital must compete with all other equity returns and ultimately with nominal GDP growth rates — something much higher than inflation (we hope). When bank dividends (if held publicly) or bank profits (if held privately) do not keep pace with nominal GDP growth, then the bank becomes a former bank, regardless of how cheap or expensive overnight cash loans are.

Corporate bonds (all sorts of corporate debt issuance) bought by households through mutual funds will compete with loans directly from the banks.

Unfortunately not. Loans are a real estate phenomena for a simple reason: the use of leverage requires strict collateral requirements.

To see this, in a 12:1 scenario, 1% of “risk” born by the bank translates to 12% of risk borne by bank capital. Therefore the bank should, in theory, charge 12% more to the firm than the private credit markets. Remember that the bank must purchase capital from these markets at the private sector interest rate, regardless of FedFunds. Banks mitigate this risk by using collateral and underwriting standards. But it is a large head-wind, and this generally limits banks to making loans on unproductive enterprises:

A productive business has equity value in excess of the tangible liquidation value — in some sense, this is the definition of “productive capital”: it adds value above and beyond the cost of the materials and land employed. This is as opposed to non-productive capital such as land or housing owned by rentiers, in which they add very little value (other than basic maintenance) and this type of collateral is more suitable for protecting banks against losses. A company whose value is human ingenuity and good management has little to offer a bank in terms of collateral. A McMansion is much better. This is why lending is everywhere and always a real estate phenomena.

This is also why it is generally not welfare-enhancing to encourage loan growth, as the use of leverage forces banks to seek out — fox-like — the least productive investments possible. Those are the ones that bear the least risk for the bank, and on which the bank makes the most profits.

Coming back to banks the fed funds’ level does have an effect because if the deposits are moved to another bank, the loan giving bank may find itself owing the loan amount in the overnight market.

No, there is netting, so this does not have a noticeable effect. The data is clear: MZM own rate trends far below FedFunds. No investor gets a FedFunds rate for an overnight commitment, unless FedFunds is at zero.

Theres is another reason for low rates. There is an idea in PKE literature on pricing of goods. Its called Markup pricing –

I agree with markup pricing generally, but there is little relationship between markup rates and FedFunds, because FedFunds does not set the private sector interest rate, let alone the return on capital requirement. If you look at the GDP data, you will see that return to capital is relatively fixed even as FedFunds has bounced around. Saez has good data on this, but you can check NIPA yourself.

Hi RSJ,

You are introducing too many complications here. So let us debate a few things one by one.

The empirical fact that the Fed cannot even defend the overnight rate is not actually a proof that it cannot. Right now, even though it pays interest of 25bps, the Fed Funds average to numbers like 14-16 bps everyday. Ben Bernanke himself knows why this is happening – Agencies do not get paid on the interest and hence lend the excess cheap. Solution: pay interest to the agencies as well. As Warren Mosler says in his blog, the government is the monopoly issuer and can set the “price”. Scott has many papers on this where he gives every possible detail. I agree completely with you on liquidity preferences of the investors and the same argument can be used to show how the Fed can set long term rates as well. Surely some investors will buy the bonds at $99 – the remaining balance just stays as excess reserves – nobody can get rid of those excess reserves by investing somewhere else. The liquidity preferences will determine how many of the investors end up buying the 1y at $99. It may well be zero which means nobody buys the bonds. The neoclassical way of saying it is that liquidity preferences will determine the interest rate. But neoclassicals miss important accounting identities. The present system is the latter but operationally there is no reason for it to be the former. In the modern monetary theory way of describing the auction system is that the liquidity preferences will determine the rate and yes the long term yields can change. But this is just because of the way the system is designed. Warren Mosler’s site has videos and you can see how he makes this point clear about the government being the monopoly issuer of currencies and its implications.

You may have to read Bill’s proposals carefully. I think he is also saying that banks are something like a PPP. You can read it in the post Operational design arising from modern monetary theory. The central bank lends the banks with no upper limit and that there should be no interbank market and all settlements happen directly at the central bank etc. Not sure about capital requirements but I am assuming that in this proposal such a thing is not a constraint for lending. Banks can lend infinitely I assume.

If banks can lend without constraints, surely the corporate bond market will also follow it and yields will end up being low.

Yes I have ignored the equity markets but what about them ? It is an opportunity to chase high returns but will surely not come in the way the non-equity markets function.

Bill and Scott’s arguments are not just to describe the way the system works but to make use of the full potential of the way the system works.

I agree with you in most points but IMHO, we are debating because you maybe describing a world with many constraints and I am arguing for removing the constraints. For example I completely agree with you that in spite of really big operations like Quantitative Easing, the Fed has not been really able to control the yield curve much because it has no control on the liquidity preferences of investors and has only controlled the supply available and thus to some extent the yields. But this is just because the way the system is designed. This is not to be taken as a proof that it cannot control – the central bankers simply do not know the modern monetary theory.

Hi RSJ,

Continuing from 18:46

I think I understand your point now. You are saying that capital adequacy requirements are important and for banks to lend, they need to raise capital from investors who have opportunity costs including equity. Banks are thus forced to increase the interest rates on loans, independent of the level of Fed Funds rate to target a profit level.

The idea of capital adequacy however is another neoliberal concept. James Galbraith who also belongs to the modern money camp says this in the levy article Financial and Monetary Issues as the Crisis Unfolds

The idea that bank risk taking can be effectively limited by capital requirements is a neoliberal illusion, stemming directly from the concepts of perfect information and market discipline. In reality, capital requirements are neither a barrier to risk taking nor a cushion against losses. They are a tax on the operation of institutions and a source of conflict as declining valuations wipe out the cushion for individual institutions and increase the pressure on the system as a whole. Yet the problem is to minimize financial behaviors that are likely to bring down the system. The plain lesson of history is that this can only be achieved by national (or transnational) regulation of institutional behavior. Therefore, the task of governments going forward is to establish and enforce effective rules for institutions, citizens, banks, taxation, and mortgages that are the only serious

antidote to reckless finance

The Basel 2 requirements in my opinion contributed to the crisis since banks did all sorts of innovative stuff and paid the ratings agencies heavily to rate securities as AAA.

I think Bill would do away with any capital requirements and instead enforce risk management through active policies than just using poorly modeled requirements in the Basels. You should ping him on this one – I remember reading in a post that he will be writing on the capital requirements and various issues associated with it as a post.

Good discussion Ramanan,

Yes, I am claiming that capital requirements together with the call money rate set a bank’s cost of capital. Therefore FedFunds is a floor, but not a ceiling on borrowing rates.

I do agree FedFunds is a ceiling for MZM own rate, so that if FedFunds is zero, then MZM own rate will be close to zero. I also agree that if FedFunds is too high, then MZM Own Rate will be positive, which is unfair — you are getting free returns without parting with liquidity. Generally MZM is about zero already.

But MZM Own Rate is not really an interest rate in the traditional sense — i.e. that it represents the cost of parting with a certain amount of liquidity. It represents the return on zero parting of liquidity. It is nonsensical to claim that by an additive process from MZM you get the cost of parting with liquidity for 1 year or 30 years. You start with the expected nominal GDP growth rate which is the return on equity — the maximum capital commitment and then you subtract to get yields corresponding to lower levels of capital commitment.

I also claim that bank lending rates influence the relative prices of those goods and services that meet bank collateral requirements. Bank loan rates do not directly alter the liquidity preferences that set (non-zero day) discounts for reduced levels of capital commitment.

I agree that if banks faced no capital requirements and zero cash costs, then bank lending would have zero liquidity cost and could in theory create unlimited purchasing power. I argue that this is undemocratic and not welfare enhancing.

As you point out, capital requirements cannot ensure that a bank avoids losses, but that is not their role. The effect of capital requirements is to ensure that there is a cost to making a loan, and that this cost is borne by the bank investors.

Making a loan is the creation of purchasing power, and as a result, someone (the investor that funds the bank) must voluntarily agree to suppress some of his/her own purchasing power while that loan is outstanding. Not necessarily on a 1-1 ratio, but on some ratio with a lower bound for each dollar lent. Moreover, if the loan is not repaid then the loss must be born by the investor. So a capital requirement ensures that the investors risk some of their own capital prior to making loans, and that making loans has costs. They are not guarantees against bank failures.

Only the government as a currency issuer should be freed from liquidity costs. Banks, like all other non-government actors, must pay a cost in proportion to the amount of purchasing power they create. If you remove capital requirements, you effectively make banks currency issuers.

This has effects on relative prices. When a loan is made, the debtor has their purchasing power enhanced and is able to bid away a good from the rest of the market. The total cost to the rest of the market is the capital ratio, say 1/12 the amount of new purchasing power created. As this ratio shifts from a 1 to 1 ratio to a 10 to 1 ratio, the net result is that more and more relative prices are set by bank lending decisions — i.e. by expectations of future prices as interpreted by bankers, and fewer prices are set by current incomes. This increases instability and distorts market pricing, causing non-productive assets such as land to become expensive. Low borrowing rates subsidize rentiers.

Getting rid of capital requirements entirely, (or setting an infinity to 1 ratio) together with ensuring that banks have ready access to unlimited reserves at zero-cost will castrate government and the non-bank markets. People could borrow to pay taxes, or borrow for anything. All relative prices would be set by bankers. If a bank approves a loan for X on a car, the price of the cars jumps to X. In such a world, the amount of fiat money is meaningless, as everything is controlled by bank credit allocation.

You can argue that such a situation could be prudently managed by all-knowing incorruptible on-the-spot regulators. I am skeptical.

One thing missing here is a sense of realism. Systems need to be robust. We need multiple overlapping checks that can detect and recover from failure. The big problem with bank regulation is two-fold:

* regulatory failure, primarily capture

* price and income uncertainty

Regulatory failure is made easier the more ambiguity there is about a bank’s financial position, and the more flexibility there is in meeting regulatory requirements. We need more transparency, simpler rules, and less discretion as to lending standards, not more. Purchasing power flexibility should reside with legislative fiscal policy, not with private sector banking decisions.

The government can always elect to bail out or capitalize banks in a time of crisis, or to buy up houses to boost their prices — as part of a democratic legislative process.

Therefore the “self-assessment” provisions of Basil II are horrific in enabling regulatory failures. The simpler and more obvious a capital requirement is, the easier it is to enforce.

Needing cash is the simplest check — it is hard to lie about being short of cash. Therefore there should be a non-zero cost to cash and banks’ cash needs should be monitored. This is an argument for interbank lending markets, as spikes in these rates mean that banks are desperate for cash and have therefore been lying to regulators about their financial position.

Next, simple capital requirements not dependent on bank self-assessment or subjective third party assessment, but merely on the asset-class held.

It might be welfare enhancing in a utopian scenario to allow capital requirements to fluctuate with the business cycle. But fluctuating requirements are easier to subvert. Clear and constant capital ratios are better, overall, because the resulting system is more robust, even if not theoretically ideal.

Fiscal policy should regulate the business cycle, not regulatory forbearance.

Banks not meeting capital requirements should be promptly closed, with bank investors suffering the full losses of the closure. No one should be able to roll-over non-performing loans or otherwise hide losses in an attempt to prevent their pledged capital from being seized by regulators.

But even with incorruptible regulators there are theoretical constraints that limit the effectiveness of things like debt to income or debt to collateral ratios. First, the value of the collateral that a loan is made against is set by the willingness of the bank to make the loan. The very act of creating purchasing power shifts the relative prices in an economy, but in a potentially unstable way. Even perfect regulation that enforces seemingly good collateral requirements will lead to housing and land bubbles. So you need something in addition to these requirements.

But the problem runs deeper, as credit-creation also influences incomes. You can say “do not allow debt to income to exceed 3”, but loans are against expected income. And the very act of lending creates dissaving that filters into increased incomes elsewhere, which leads back to increased lending. And you do not know whether this cycle is sustainable or not. Those increased incomes could be temporary. There is fundamental uncertainty, and a well-documented bias towards optimism.

Therefore it is insufficient to impose debt to income or debt to collateral requirements. You must also require that bank investors have skin in the game, and pay a cost for each dollar lent.

I do not believe that eliminating capital requirements, providing zero cost reserves to banks, and eliminating mark to market are conducive to effective bank regulation and a government monopoly on currency issuance.

RSJ,

Yes good discussion. Good to discuss things which Minsky himself worried about.

There is one big thing that differentiates banks and the government/CB. This is the power to tax. It is true that banks can issue loans and if they are granted powers to give them at the cheapest possible costs, they may start lending aggresively. On the other hand, taxes are terrific tools to control aggregate demand. Government spending and taxes can act as great tools to control of aggegate demand and hence prices. Indeed they have been doing that already and mainstream economists don’t seem to recognize that. As Warren Mosler puts it, if the prices start moving up, the US govenment can spend $3T less than what it spends. Government spending and taxes act as great automatic stablizers. The idea of the government being the employer of the last resort and buffer stock programs are not only for welfare – they can act as a good stablizers too.

Why do you think that if the bank grants a loan of x the price of the car will jump to x ? When there is a purchase, there is a sales tax associated with it. When people start consuming a lot, the taxes will also increase proportionately and lot of money will leave the monetary system because taxes don’t go anywhere.

Of course all this comes with the assumption that the guys sitting at the fiscal level are doing their jobs honestly which is a big assumption. On the other hand, Basel models seem to completely miss the point. The economists who actually designed it, had no clue that the crisis was coming.

I agree with you in most points, but in this comment, I just wished to point out to you the importance of government spending and taxing.

RSJ,

(Continuing from 20:17)

One more thing. The rentier income in question is not just the income on bank deposits but also interest payments on government securities.

Happy Halloween, Ramanan!

I just wished to point out to you the importance of government spending and taxing.

I agree with this importance, with the need for a jobs program, and with not requiring that bond sales match deficit spending 1 to 1. I agree with all the accounting identities. Setting FedFunds to zero, or requiring zero bond sales does not flow from any accounting identity, but from a mental model in which the private sector is passive and credit growth is constant. That is the only rationale for removing capital requirements, bank cash costs, and arguing for low borrowing rates. Only if you think that the quantity of money borrowed is independent of the rate would you believe that it is a benefit to have lower rates.

Just as the gold standard mental model is flawed, so this rigid private sector mental model is also flawed. You need an integrated model in which the actions of government affect and are affected by what happens in the private sector debt markets. There is also not a lot of realism in terms of practical implementation issues.

As Warren Mosler puts it, if the prices start moving up, the US govenment can spend $3T less than what it spends.

Only assuming the private sector is passive. The private sector can create its own purchasing power in the form of loan growth even as the government drains. This can cause prices to rise even if fiscal policy is attempting to counteract the increase. As this happens, leverage increases. Therefore limiting leverage is critical to allowing fiscal policy to be effective.

Eventually the government’s efforts at draining will win in the end, but possibly in an ugly way and after a long lag. We saw this in the Clinton deficit years and in the Bush II years. I would also add that operationally it is not easy to cut spending — you cannot leave a highway half built, shut down a school, or cancel a jobs program. And operationally it is not easy to change tax rates so often, as you are imposing a lot of income uncertainty on households. You cannot cut people’s social security payments when inflation rises — again, more realism is called for. You will end up floating bonds in an attempt to control purchasing power, because doing so imposes the least social costs.

The rentier income in question is not just the income on bank deposits but also interest payments on government securities.

When you buy a 1 year government bond, you agree to not spend money for one year, making room for the government. I agree that in many cases you do not need to do this, because government spending need not be inflationary at all. But to the degree that you want a tool to limit private sector purchasing power in order to “smooth” government expenditures (i.e. keep building those schools and roads and sending out the social security checks even in the face of increasing inflation), then you will need to float bonds.

The bond purchaser, by agreeing to not exercise his purchasing power, will demand to be compensated, because he could have used that money to purchase capital which would have earned the GDP return over that time period. That is why I keep saying that government does not control the rate of interest demanded. People only buy the bond if the fixed payments compensate them for the opportunity loss. This ensures that the bonds are priced fairly, at least in terms of people’s expectations. In times of recession or deflation, people’s expectations of growth falls and the short dated yields fall as well. In that case, there is no benefit to issuing bonds and you can expand the currency base, provided you have an iron grip on bank lending when the economy improves. In the real world, banks have an iron grip on the legislature, so I can see why officials would prefer to float bonds as a practical matter, even if it is not theoretically necessary.

I agree that expectations can be wrong, in which case yields are discovered to be too cheap or too rich after the fact. From the 1980s-1990s, bond yields were far too high in the U.S. In Japan today they are far too high. Even short term yield are too high in Japan, as they are currently undergoing price deflation of -2.5%.

You can argue, “all money comes from the government, and therefore there is no public purpose served by the government creating money and then paying people not to spend it.” But that is wrong, all currency is issued by the government, but the majority of purchasing power is in the form of credit. What you have in your bank account is primarily credit, not currency. It is not backed by currency on a 1-1 ratio. If the government decreases the amount of currency by 5%, that does not mean that people’s bank accounts decrease by 5%. They do not wake up in the morning to find lower balances. It just means that the amount of currency backing those accounts falls, and the leverage of the bank increases.

Hopefully, if you have fixed leverage requirements, and non-zero cash funding costs, the result will be a decrease in lending which will cause the money in people’s bank accounts to decrease as well as loans are repaid and fewer new loans are issued. At the same time, there is also an effect from lower private sector sales to government and increased tax payments, but the second channel is dwarfed by the credit channel, and both channels are quite slow moving and can impose heavy social costs.