My friend Alan Kohler, who is the finance presenter at the ABC, wrote an interesting…

The last thing we need is a return to fiscal surpluses and rising household debt

There are some Op Eds that are bad, and then others that transcend that standard to become terrible. Such was the case last week when I read this article in the Australian press (Sydney Morning Herald) (February 18, 2022) – It’s time to return to Costello economics, whoever wins the federal election – which was written by a former advisor to the last Labor Prime Minister in Australia. The article is dishonest in that it completely ignores the most significant aspects of the period he seeks to eulogise. It is also scary if it reflects current Labor Party thinking, given the author’s previous associations.

For readers abroad, the reference to “Costello economics” is to the Conservative Treasurer Peter Costello’s period in office from March 1996 to December 2007, during which the federal government ran fiscal surpluses in 10 out of the 11 years.

This period has been held out by many economists and political types as being the historical norm that macroeconomic policy should aspire to replicate.

Such aspiration fails all reasonable tests – historical context, economic soundness – to name just two.

For a former Labor Party advisor to recommend we use this period as a benchmark tells us how far gone the Australian Labor Party is with respect to macroeconomic policy.

The Op Ed writer sets the fiction from the outset by claiming that:

Voters … expect … [the Federal Treasurer] … to prudently balance the federal budget …

This is what one calls making up stuff as if it is true, in an effort to make it true.

There was a survey conducted in May 2021 on – Attitudes to tax and budget priorities – which found that:

Spending on government services like health and education was the single most popular priority …

Decreasing the deficit and repaying debt was the least popular, chosen by one in 10 …

So, some voters might want the Treasurer to balance the spending and tax revenue, but they are a small minority.

The Op Ed writer thinks that Peter Costello was the “maestro in the modern era … of course”.

The “of course” is added so that we accept the ridiculous proposition without question.

Only a fool would think Costello was a maestro.

He was a disaster for his period and has left a legacy that makes policy making even more difficult.

Apparently, Costello “drove the electoral success of the Howard government by consistently delivering both federal surpluses and family tax cuts.”

The reality is that Howard’s political success was more about beating up fears about our external border (the ‘boats are coming’) and vilifying minority groups, particularly indigenous Australians and using that vilification to engender a ‘them and us’ mentality.

The Howard government’s economic strategy was about short-termism – feed a household consumption boom with debt to delay the reckoning which came in 2008.

The Op Ed author then tries the old ‘reinvent history’ trick in his praise for Costello’s era by claiming that the growth during that period was used:

… to balance the budget … Costello’s model was an evolution of Paul Keating’s formula, but Costello delivered it more consistently than any treasurer in modern history, thanks to monumental help from the mining boom.

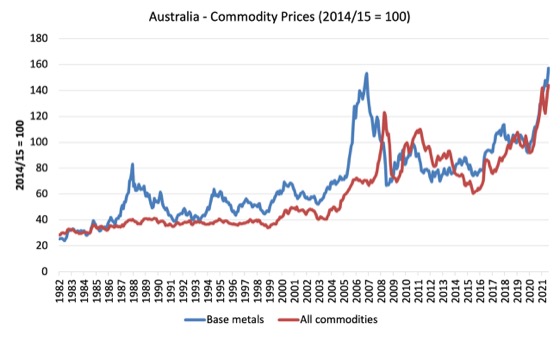

The following graph shows Australia’s terms of trade, which allows us to date the once-in-a-century mining boom that Australia experienced during the Costello years.

The relevant commodity price index shot up in early 2005 and peaked in May 2007. It recovered a little after the GFC but petered out in 2018.

So, the benefits of the export boom really only helped the Howard government in terms of maintaining economic growth and tax revenue growth towards the end of their tenure.

It is stretching the truth to say that the surpluses recorded prior to 2005 had anything to do with the external sector boom that the nation experienced.

The extraordinary aspect of the Op Ed is its total failure to mention household debt and the credit boom that followed the widespread deregulation of the financial markets in the 1980s.

The deregulation created a new industry – financial engineering – which is a nice term for the predatory behaviour of the banks who thought nothing of pushing credit cards and big loans onto anything that moved including pre-school children (unsolicited credit cards would turn up in the mail with large limits – addressed to children).

It was a frenzy. The more credit that could be pushed onto households the better for the banks.

There was scant regard at that time for proper credentials and prudence.

The same behaviour occurred globally, and, as we know, eventually blew up in the form of the GFC.

There was another factor that is also important.

In the 1980s, the Labor government (pre-Howard/Costello) created the circumstances where for the first time in data history, real wages growth started to lag behind productivity growth.

They engineered that outcome throuh their wages policy and industrial relations legislation that effectively reduced the capacity of workers to bargain decent wage outcomes.

Real wages also were cut during this period in the promise that the corporate sector would use the increased profits to lift their dismal investment rate.

They failed to honour that part of the deal.

The upshot was that real wages growth was flat and negative at times and the wage share in national income started to fall dramatically.

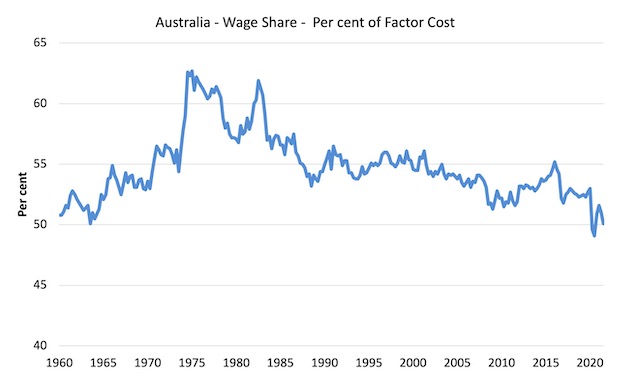

Here is the graph of the wage share from 1960 to the September-quarter 2021.

Two points to note:

1. By the time Costello became treasurer (March 1996), the wage share had slumped.

2. Over his tenure as treasurer it continued to decline – transferring millions of dollars of national income away from workers to profits.

The investment ratio did not respond but fat executive salaries did!

So the two developments in the period preceding and during Costello’s tenure as treasurer worked together to create the circumstances whereby Australia was able to increase GDP while the fiscal drag coming from his fiscal surpluses was increasing.

In this blog post – The origins of the economic crisis (February 16, 2009) – I showed how the GFC was a direct result of these developments.

The dramatic shift from fiscal deficits to surpluses from the mid-1990s onwards under Treasurer Costello was only possible because of the corresponding deterioration in private domestic sector indebtedness.

With Australia recording a fairly stable external deficit of some 3 to 4 per cent of GDP, the only way that Costello was able to record the fiscal surpluses under his austerity strategy was because GDP growth was maintained by growth in household consumption expenditure.

And with real wages growth no longer driving that consumption growth, households turned to credit to maintain their matieral living standards.

If the credit boom had not have occurred, Costello would have struggled to record one surplus much less 10 in 11 years.

What Costello relied on was squeezing wages and the gap being filled by a run-down of household saving and ever increasing indebtedness.

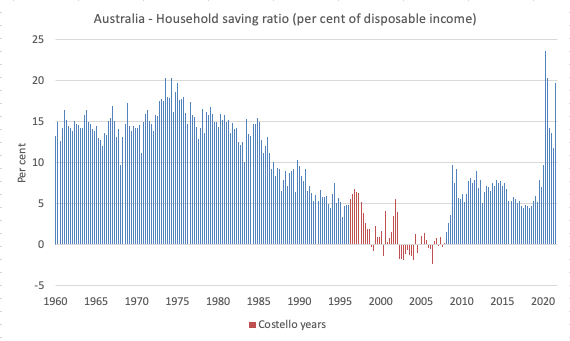

The following graph shows the history of the household saving ratio (as a percent of disposable income) from 1960 to the September-quarter 2021.

The supplementary table summarises the decade averages and the Costello period.

| Period | Saving rato (per cent) |

| 1960s | 14.4 |

| 1970s | 16.2 |

| 1980s | 11.9 |

| 1990s | 5.1 |

| 2000s | 1.4 |

| 2010 on | 7.8 |

| Costello years | 1.3 |

These developments were much more fundamental to Costello’s surpluses than the later mining boom, which just made it even easier to generate the revenue without undermining growth.

The point is that the most significant aspect of Costello’s tenure as treasurer is that his policy approach squeezed the non-government sector of liquidity and maintained the flat wages growth, and then drove the saving ratio into negative territory for the first time in recorded history.

That is the only way he was able to record those surpluses.

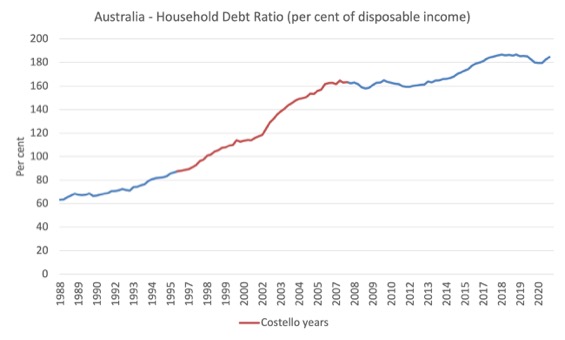

And the lasting legacy is shown in the following graph which depicts the evolution of household debt (as a percent of disposable income).

This is the standout result of the Costello years – and the failure to mention in by the Op Ed author Charlton indicates his lack of transparency. It is simply dishonest not to acknowledge this extraordinary shift in household balance sheets and their importance for sustaining growth during this period.

The problem with Costello’s approach is that it was an unsustainable growth strategy. Ultimately the private domestic deficits and the increased precariousness of the household balance sheets make it impossible for households to keep borrowing and funding their consumption growth, while real wages remained flat.

With that degree of private debt precarity, even small shifts in the environment (interest rates, unemployment etc) became significant triggers for bankruptcies and defaults and a collapse in aggregate demand growth.

At that point, the fiscal drag cannot continue as the economy goes into deep recession.

The mining boom saved Costello from that slowdown but only for a few years, with the GFC coming just after he was thrown out of office – a failure.

The other important point to note is that commentators keep talking about ‘when will we get back into fiscal surplus’ or ‘when we we return to Costello economics’.

The con job is to lead people (with short memories) to believe that the Costello period was normal and can provide a benchmark upon which we can judge contemporary policy settings.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The Costello period was aytpical or abnormal in every way.

For most of our recorded history the Australian government has run steady and continuous fiscal deficits, which provided the spending support to allow the non-government sector to save overall.

Those high household saving ratios in the 1960s, for example, were funded by income growth that was aided by strong fiscal support from the federal government.

The Costello period of surpluses was an aberration created by a massive credit binge and households consistently spending more than they earned and increasingly becoming indebted.

As I said – that combination is unsustainable – so it could never be the aspiration benchmark that the Op Ed author Charlton claims.

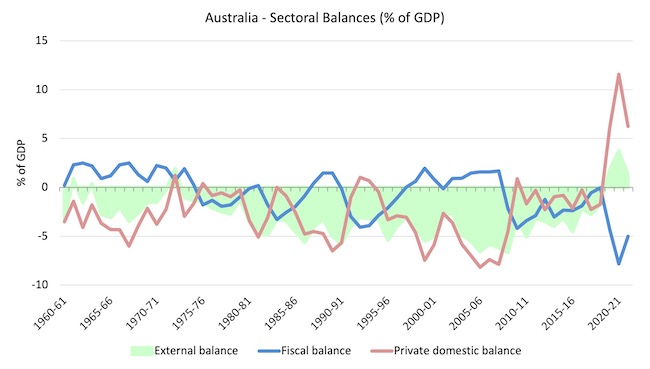

The other way of thinking about his is to consult the next graph, which shows the history of the Australian sectoral balances since 1960-61 to 2021-22 (the last two observations being forecasts from the 2021-22 fiscal statement supplied by the Australian government).

The Costello years began in 1996 and ended in late 2007.

You can see that while there was some increase in the external deficit during this period, the major shifts were in the move into surplus by government and the increasing deficit being borne by the private domestic sector.

The private domestic sector has never run that larger a deficit in the recorded history.

Also note the sharp rise in the fiscal deficit during the pandemic has allowed the private domestic sector to shift into surplus (saving overall and reducing indebtedness).

Charlton thinks that the current period of elevated deficits will be rejected by ‘voters’ because they will:

… realise that gigantic public spending is one of the factors hurting their cost of living. This massive spending has flooded the economy with cash, fuelled the consumer boom, helped to push prices higher and ultimately put upward pressure on interest rates.

I think the ‘voters’ are not as stupid as Charlton.

Only a fool would think the fiscal deficits that have been increased to support household incomes as the pandemic prevented workers from working etc were unnecessary.

What would have happened if the government hadn’t have increased their spending to rather elevated (relative) levels?

A deep recession, a huge rise in joblessness and households ravaged not only by Covid but also foreclosures on their mortgages, mass evictions from rental properties, a wipeout of their savings, and more.

The social consequences that would have followed would have been shocking.

The ‘voters’ know that.

They also should understand that the rising cost of living is because workers are sick and cannot deliver goods to where they need to go, that ships are stuck in the wrong places, that planes haven’t been flying and the rest of it.

Charlton thinks we:

… need to rapidly pivot from crisis economics back to Costello economics.

The problem is that household debt cannot rise much further without a meltdown occuring.

Real wages are still falling.

And if the government tries to pursue a fiscal surplus strategy it will have little impact on the cost of living rises at present but a massive impact on GDP and employment growth, which will compound the precarious household balance sheets.

We would then have a massive supply chain constraint interacting with a demand collapse.

That is a shocking thought.

Voters would reject that strategy.

Conclusion

The cost of living problem requires patience – we need to wait out the supply chain impediments.

The fiscal support needs to be maintained to ensure we don’t kill the real side of the economy as we wait out the supply side.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Costello’s budget surpluses were also enhanced by his mauling of public health expenditure and public education expenditure, particularly the university sector, which eventually had to effectively privatize to survive (i.e. bring in vast numbers of overseas students, probably to the disadvantage of Australian students).

I am confused by the comment “And the lasting legacy is shown in the following graph which depicts the evolution of household debt (as a percent of disposable income)” and the graph that follows. This graph appears to show that debt fell steadily during the Costello years, following a trend that began in the mid 70’s and continues today, though with considerably less noise during the Costello years than at other times. Surely this is not correct?

I have just read the blog post – The origins of the economic crisis (February 16, 2009) – linked by Bill and found this entry from him in the comments…

“Dear Alan

Thanks for the comment. Blogs can be educative perhaps. I guess we will learn this the hard way but eventually we will learn it. The middle class are being levelled by this crisis and they are the ones that swing back and forth to substantiate paradigm changes.

best wishes, bill”

13 years on and we’re still waiting for the message to sink in to enough middle class minds to make a difference.

In the sectoral balances chart, should the green bit be the other way up. Are they not supposed to sum to zero?

Let’s not forget that Peter Costello is the chairman of Nine Entertainment, publisher of that editorial. That makes it look like a disgusting bit of legacy-polishing. It is a turd that is being polished.

As a direct result of his cuts and austerity, our productivity growth is in decline. Unless dramatic action is taken (and the opposition is not promising drama!), we will all be paying for Costello’s surpluses for decades.

He still has that smug look on his face, but the kids paying university fees will be writing his history.

Ah, that looks better! A far more depressing graph.

Acorn,

“In the sectoral balances chart, should the green bit be the other way up. ”

The chart is confusing. The balances as they are in the actual SBE are not.

It’s a question of how you want to show the government deficit. In the SBE, a government deficit is a positive number but on the graph it is shown as a negative percentage of GDP. We tend to think of a deficit as a negative number. So it’s shown this way for exposition purposes. Costello’s surplus shows up on this graph as a positive percentage of GDP. Which is not counterintuitive.

Acorn,

Of course the other way to write the SBE is:

(S – I) = – (T – G) + (x – M)

private sector surplus = – government surplus + trade surplus.

Here the government surplus is a positive number in the SBE.

Australia’s current account was in surplus during 2019 to 21. That is the external sector was in deficit with Australia. The external deficit plus the fiscal deficit equals the private sector surplus. (-4)+(-7.5) equals (+11.5).

Same for Canada in the ’90s – just substitute Paul Martin for Costello …

Makes me think of Elvis Costello’s song, Less Than Zero. About the fascist fellow Mosley Oswald from the 30’s in Britain. What’s the outcome of a balanced budget. Less than zero.

Recessions are *always* the result of private debts that can’t be paid. And since private debts are ultimately payable with government dollars, a government budget surplus, which reduces the private sector’s stock of government dollars, makes recession more likely.

Peter Costello got the job as Treasurer because he was happy to act as a puppet for those that really rule Australia – the neoliberal bureaucrats at Treasury and the RBA that really worked for the big banks; the Institute of Public Affairs that wrote the policy agenda for the conservative Coalition parties; the Liberal Party organisation power brokers and the various big business and finance sector associations and lobbyists. There was a lot of easy profits to be made by greatly increasing household debt and federal government spending austerity brought that about.

Our worst ever Treasurer Peter Costello and our worst ever Prime Minister John Winston Howard deepened the neoliberal agenda and were both scammers of the Australian people. The ALP were and remain not much better on these issues.

I have no faith that the Australian electorate has learnt that federal deficits under Australia’s circumstances are usually a good thing and that the federal debt is of little consequence, even after the recent large deficits associated with the pandemic. The electoral sheep after a little mass media prompting will soon bleet that we must all tighten our belts and pay back the debt so as not to burden future generations and then elect another neoliberal government.

Unfortunately for Charlton, the moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on…

In a book he wrote on the Howard-Costello era in 2007* there’s a chapter titled “The Budget Surplus Myth” wherein he ridicules Costello’s claims for why the economy was (supposedly) doing so well under his custodianship.

As I read it I wondered if he might’ve been getting his insights (some anyway) from Bill.

*”Ozonomics: Inside the myth of Australia’s economic superheroes”

While domestic U.S. economists debate whether the Fed will get tight by raising interest rates, the federal government ran a $129 billion surplus during the first quarter of 2022 (ending January). As tax revenues soared, both federal and state and local tax coffers are bulging with yet further increases likely as all that stimulus runs into ongoing government tax collections. And all those conservatives and liberals want to raise taxes further. Is there any doubt that they are setting us up for a recession in 2023?