These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Bank of England Governor just didn’t go far enough

The Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey caused a stir last week when he said that British workers should not get wage increases in the coming period. This was a day after the Bank of England raised interest rates, presumably because they have some theory that that will cure Covid and get trucks moving again. There was general outrage expressed by a range of voices, who often are not on the same page – unions, corporate interests, the ‘high wage’ aspiring Tory government (perhaps). The outrage was, unfortunately, personalised with critics pointing out that “Bailey was paid £575,538, including pension, last year” (Source) and hasn’t offered to give any of that fat cat salary back. But as in most things, getting personal usually misses the point. Beyond the rage, in a sense, he was correct to highlight that if the current supply-induced price pressures trigger a wider distributional struggle then accelerating inflation will result and the policy implications of such an event as that will be very damaging to workers in the UK. But, the problem was that he didn’t go far enough. This won’t be a popular view but it comes from studying inflationary mechanisms all my career, which means I think I understand how supply constraints move into a generalised wage-price spiral, which then causes worker more damage than some wage restraint. And, remember, we are talking about Capitalism here – not some profit-sharing, collectively-owned nirvana. The Bank of England Governor was clearly thinking that the conditions for a 1970s wage-price spiral are approaching for the UK, which means that wage restraint would be sensible if the goal was to insulate the current supply shocks arising from the pandemic and aberrant behaviour by OPEC etc and render them transitory. I don’t think the conditions are present yet and he should have generalised the concern to focus on other more obvious triggers that do exist at present.

History

In October 1973, as retaliation against the nations that supported Israel in its defence of its illegal occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights and parts of the West Bank against Egyptian and Syrian-led forces, the Saudi-led OPEC cartel imposed an oil embargo.

The embargo ended in March 1974 and by then the oil price had risen 300 per cent.

A second oil shock followed in 1979.

These shocks are supply-side disruptions that can have further effects as they disrupt the income distribution.

Initially, the supply shocks are usually once-off impacts – the price level rises.

If nothing else happens then there is no inflationary process set off.

Remember that inflation is a continuous increase in the price level and so a once-off adjustment upwards does not constitute an inflationary episode.

In 1973-74 OPEC decision was a massive cost shock for the oil-importing nations, which meant that real national income in these nations was now lower as more of the GDP had to be paid out to foreigners.

Similarly for those, like Australia, who price local (lower cost) oil at foreign prices, as a corporate welfare stunt to large oil companies who blackmail the government, using the threat they will stop exploration if they don’t get the higher price guaranteed.

The question then was who was going to take the real income loss – the workers or the corporations or some mix of both.

At the time (1970s), the growing concentration of capital in the Post War period meant that the large oligopolies had price setting power, which meant they could set margins over unit costs and protect them in real terms, knowing that it was likely all firms in their sector would do the same thing.

And trade unions were much more powerful than they are now.

This was before the relative decline of manufacturing and the rise of the service sector, the latter which makes organising union members much more difficult.

This was before the increasing participation of women in workforce which has reduced union membership.

This was before the mass unemployment which has reduced membership.

This was before the raft of legislation in different nations that has legally curtailed the capacity of unions to secure wage rises.

So unions had the capacity then to engage in real wage resistance, which is a term that refers to using their industrial strength to ensure that the price rises that followed the cost shock (as firms moved to protect real margins and pass on the real income loss to workers) were translated into nominal (money) wage rises.

But the reality was that some group or groups (workers, capital) had to take a real cut in living standards in the short-run to accommodate the new claim on real output arising from the increased imported oil prices.

At that time, neither labour or capital chose to concede and there were limited institutional mechanisms available to distribute the real losses fairly between all distributional claimants.

The resulting wage-price spiral and subsequent accelerating inflation came directly out of the distributional conflict that occurred.

Another way of saying this is that there were too many nominal claims (specified in monetary terms) on the existing real output.

This is sometimes called the “battle of the mark-ups”; the “conflict theory of inflation” or the “incompatible claims” theory of inflation.

Sometimes this is referred to as “cost push” inflation because its initial source is a push upwards in costs that are then transmitted via mark-ups into price level acceleration especially if workers resist the real wage cuts that capital tries to impose on them – to force the real costs of the resource price rise onto labour.

Ultimately, the government can choose to ratify the inflation by not reducing the nominal pressure or it can break into the wage-price spiral by raising taxes and/or cutting its own spending to force a product and labour market discipline onto the “margin setters”.

The weaker demand forces firms to abandon their margin push and the weakening labour markets cause workers to re-assess their real wage resistance. That is ultimately what happened in the 1970s.

The government has other policy tools available to it to break into a wage-price spiral.

For example, cost pressures come from administrative pricing decisions, which include indexation arrangements etc (government setting regulated energy, telecommunications, health care charges etc).

In the case of price gouging by firms with market power in times of a supply shortage, the government can introduce price controls and then pursue the structural cause through anti-trust or restrictive trade practices legislation.

But in fiscal policy terms, it is spending, transfers and taxes that are the main weapons.

I note a lot of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) activists are trying to deny that increasing taxes can be used to discipline an inflationary episode.

That denial, apparently in response to mainstream claims that it is politically impossible to adjust taxes in any meaningful way, is inconsistent with how the early MMT economists (Warren, myself, Randy Wray) conceived the situation.

Of course, the government would be foolish to adjust tax structures and rates every time the CPI blipped up or down. But in an entrenched wage-price spiral, tax changes should be used to reduce the purchasing power of the non-government sector and avoid directly targetting wages growth.

We know from the Japanese experience in 1997 and later, that adjusting sales taxes upwards, for example, has strong impacts on private spending, which in turn, reduces the motivation of firms to keep pushing up prices, for fear they will not only lose sales but also market share.

There is no truth, therefore, in the claim that the body of work known as MMT eschews tax changes as a policy tool to fight inflation.

It is just that there are many other tools that also can be used.

Back to the present and the well-paid Bank of England governor

Last week (February 3, 2022), the Bank of England hiked interest rates – Bank Rate increased to 0.5% – February 2022.

The decision was on a 5-4 vote of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) – so hardly uncontested.

It also voted to reduce the stock of government bonds held by the Bank.

The MPC decision noted that:

Underlying earnings growth is estimated to have remained above pre-pandemic rates, and is expected to strengthen over the coming year, to around 4¾%. This is consistent with the results of the Bank’s Agents’ annual pay survey, with the tight labour market, and with some temporary upward pressure on wage settlements from higher price inflation …

Inflation is expected to increase further in coming months, to close to 6% in February and March, before peaking at around 7¼% in April. This projected peak is around 2 percentage points higher than expected in the November Report. The projected overshoot of inflation relative to the 2% target mainly reflects global energy and tradable goods prices. The further rise in energy futures prices meant that Ofgem’s utility price caps were expected to be substantially higher at the reset in April 2022. Core goods CPI inflation is also expected to rise further, due to the impact of global bottlenecks on tradable goods prices.

So supply constraints combined with some stronger trends in the labour market for workers – but still nothing like a wages breakout.

The day after the hike, the governor of the Bank gave an interview with the BBC – Don’t ask for a big pay rise, warns Bank of England boss

He agreed that he was “asking workers not to demand big pay rises”.

He said that:

In the sense of saying, we do need to see a moderation of wage rises, now that’s painful. I don’t want to in any sense sugar that, it is painful. But we need to see that in order to get through this problem more quickly.

His sentiment was that he didn’t want to see the temporary price rises becoming “entrenched”.

The BBC article quotes the fact that:

In the year from 1 March 2020, Mr Bailey was paid £575,538 including pension.

That is more than 18 times higher than the median annual pay for full-time employees of £31,285 for the tax year ending 5 April 2021.

Which is irrelevant in most ways to the issue.

Yes, he is overpaid in my view and the position should be readvertised at a drastically reduced pay level while at the same time, cleaners, nurses, teachers, etc should be awarded massive wage increases.

But that is an argument about wage equity and contribution to society.

It is not an argument that is particularly relevant to whether there are propagating mechanisms that might drive a wage-spiral after an initial supply-side cost shock.

That is what the reference to ‘entrenching’ is about.

Low-paid workers can still under some circumstances engage in real wage resistance which will spark off such a spiral, although, given they have little market power, such a causation is unlikely.

So what has been going on in Britain.

The Bank of England survey suggests that earnings are growing at just under 5 per cent per annum on average (there are of-course massive differences across occupational groups).

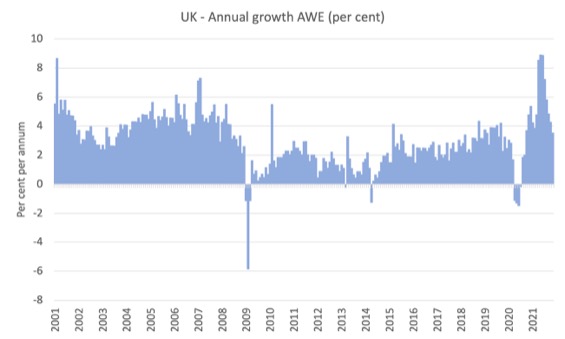

The ONS – Average Weekly Earnings data – (Whole Economy Level (£): Seasonally Adjusted Total Pay Excluding Arrears) shows that AWE grew by 3.5 per cent in November 2021 (annualised) but that rate has declined sharply in the last several months.

The next graph shows the annual growth in nominal AWE since the January 2001 to November 2021 (latest data).

In the early months of the pandemic, workers wages growth was negative and then there was a catch-up period followed more recently by a stabilisation.

I don’t think this data justifies a belief that wages growth is about to trigger a wage-price spiral.

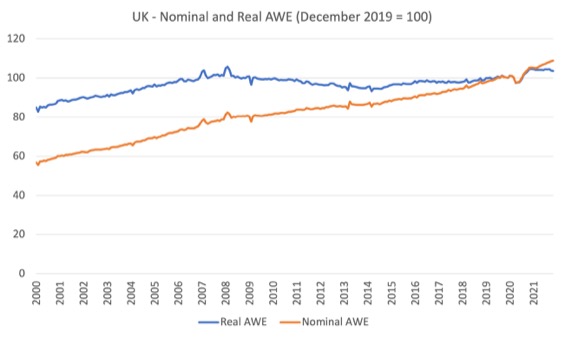

That conclusion is reinforced when I look at the data in real terms (deflating by the CPI), which is what the next graph shows.

This graph shows two indexed series: (a) real AWE; (b) nominal (actual) AWE, from January 2000 to November 2021 (indexed at December 2019 = 100).

Clearly, there has been a sustained cut in real AWE since March 2008, even though nominal AWE has been (mostly) steadily rising.

The nominal index has growth by 8.9 per cent over the period between December 2019 and November 2021, while the real index has grown 3.5 per cent.

There was some recovery in real wages in the early months of the pandemic, but, importantly, since September 2021, the real index has been in declining.

ONS also reported on January 11, 2022 that “Output per hour worked was 1.1% above pre-coronavirus pandemic levels” (Source).

That is important, because productivity growth provides the ‘room’ for nominal wages to grow without pressuring unit costs.

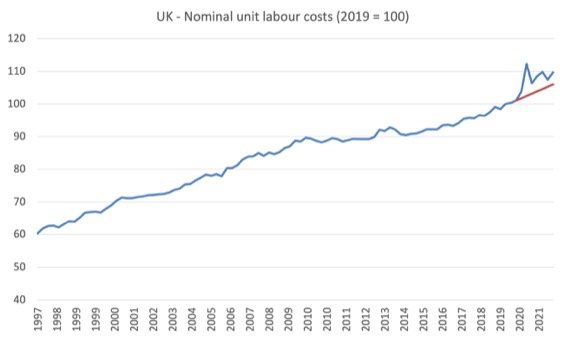

The next graph shows the evolution of nominal unit labour costs from 1997 to the September-quarter 2021.

ULC have been rising since 2016, well before the pandemic.

The red line extrapolates the average growth rate between March-quarter 2017 and the December-quarter 2019 out over the course of the pandemic.

ULC are about 3.7 points above what would have happened if the pre-pandemic trend had have continued.

But I see that as an adjustment

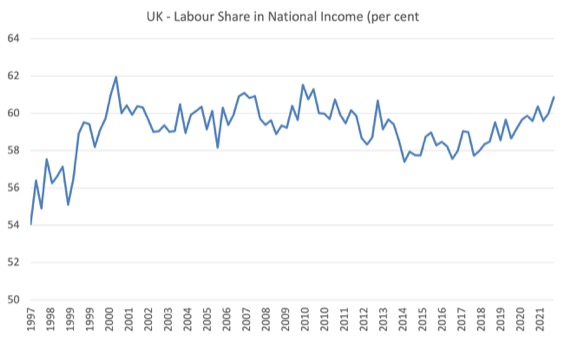

The next graph shows the wages share in national income for the whole UK economy from the March-quarter 1997 to the September-quarter 2021.

It is clear that the wages share has increased since the relative trough in the December-quarter 2017.

It has risen from 57.7 per cent to 60.9 per cent in the September-quarter 2021 (latest data).

So in aggregate terms it cannot be said that productivity growth is outstripping real wages growth – quite the opposite.

There are quite substantial sectoral differences arising from the pandemic.

For example, in the ‘Arts, entertainment and recreation’ sector the labour share fell from 76.8 per cent in the June-quarter 2020 to 60.4 per cent in the September-quarter 2021.

A similar fall occurred in the ‘Accommodation and food service activities’.

However, in general, the labour share increased in the ‘Services’ sector.

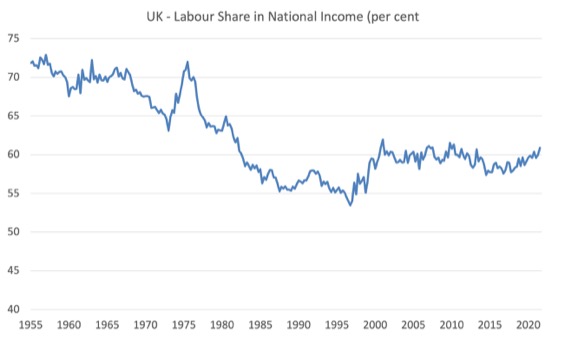

Here is a longer view of the wage share since the March-quarter 1955, which allows one to see the impact of neoliberalism (particularly the years during the second Wilson-Callaghan government and then the Thatcher years) more clearly.

Note, I have adjusted the vertical axis to accentuate the shift in the levels.

This graph shows the amazing redistribution of national income in Britain away from labour towards profits.

During those falling years, real wages growth was lagging behind productivity growth by many percentage points (and real wages growth was negative in some years).

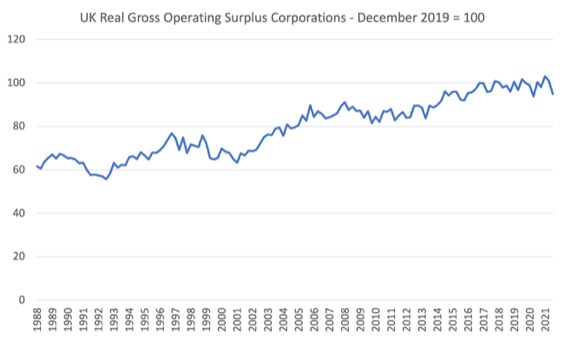

I also analysed movements in the ‘Gross operating surplus of corporations’ and this graph summarises that data.

It shows rising profits from the turn of the century, with an interruption during the GFC and again since around 2016. In the September-quarter 2021, the GOS was 5 percent lower than it was at the outset of the pandemic.

The point is that the on the profits side, I cannot see any shifts big enough or sustained enough yet to signify a wage-price spiral is being unleashed.

Conclusion

The Bank of England Governor was clearly thinking that the conditions for a 1970s wage-price spiral are approaching for the UK, which means that wage restraint would be sensible if the goal was to insulate the current supply shocks arising from the pandemic and aberrant behaviour by OPEC etc and render them transitory.

I don’t think they are given the data trends at present.

But they might.

And, more importantly, he could have also focused his attention on a number of other factors that are far more likely to trigger distributional conflict.

For example, administrative price arrangements could be frozen for several years or the government could start playing hard ball with petroleum companies.

Further, it takes two sides to sustain a wage-price spiral and the Governor was silent on the corporation pricing size.

He was also silent on the executive pay excesse that see “greedy executives are taking home millions while ordinary workers face yet another year of pay squeezes” (Source).

However, when I look at the data from all sides, I cannot see a threat emerging yet. There is a lot of noise at present and the pandemic is making it hard to know what is likely to happen.

Sure there is demand pressure but most of that is sectoral imbalances triggered by the supply issues and shifting expenditure patterns triggered by lockdowns and fear of illness.

The fact that goods production is rising and demand for goods is rising faster does not allow a conclusion that there is no supply constraint.

The shift in expenditure to goods has triggered increased production but the supply side cannot adjust quickly enough.

And meanwhile, there is excess capacity in the services sector.

Finally, the salary that Andrew Bailey enjoys is not relevant to the veracity of his comments. It is relevant to other matters where we question executive salary excesses.

MOOC starts tomorrow

MMTed invites you to enrol for the edX MOOC – Modern Monetary Theory: Economics for the 21st Century. It’s free and the 4-week course starts on February 9, 2022.

Learn about MMT properly with lots of videos, discussion, and more.

Further Details:

https://edx.org/course/modern-monetary-theory-economics-for-the-21st-century

Get on on Week 1 material as it unfolds. And there will be some special surprise events during the next four weeks that I will announce in due course to participants.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Finally, the salary that Andrew Bailey enjoys is not relevant to the veracity of his comments. It is relevant to other matters where we question executive salary excesses.”

It’s also relevant to our call for a zero interest rate policy, since in that environment overpaid bank governors, the court of the bank and the staff of the Debt Management Office would be seeking employment elsewhere – replaced by normal anonymous civil servants whose job was to clear the payment system and keep the commercial banks on a short lease.

The belief in the magical power of interest rates is legion. It’s the hydroxychloroquine of economics – works in a lab, but not in the real world.

A salutary posting.

I am still inclined to the view that, the rejection by the trade union movement of the ‘Bullock commission on industrial democracy’ in 1977, meant the rise of someone like Thatcher was inevitable. But that rejection reflected the state of the trade union movement in the 1970s. I am not convinced it has much improved over the last 50 years.

In an economy dominated by uber-like workers, quitting is a snap.

There is no formal connection between the worker and the employer, to hinder the urge to search for a better paid job.

So, in a scenario of workers shortage, it will be rather easy to get in a wage spiral, as companies vie to lure people to work for them, like truckers or taxi drivers.

On the subject of taxes, wasn’t the main objection that they after the spending has happened, so the gov could be trapped into chasing yesterday’s prices with the tax increases? Particularly a problem for taxes that take a longer period to pay, i.e. in the UK many freelances do self reporting and pay their taxes yearly.

With Australia’s international borders re-opening and the Australian government chomping at the bit to resume the pre-pandemic flood of labour into the country, it’s difficult to see the flat growth in the working age population remaining. The states may insist on requirements for entry (vaccination status) but I think the situation of many workers facing stiff competition from imported workers for jobs is likely to resume sooner or later.

I read the blogpost on East Timor just before this one – trying to catch up. In the world’s 5 richest country we have people sleeping on the streets, pensioners unable to heat homes, parents going hungry to feed their children…

The poorest and lowest-paid are going to bear the brunt of any wage restraint in the face of rising inflation being driven by petroleum hikes. Goods don’t move without petroleum so steep rises in fuel costs can run through everything downstream. Discretionary retailing and service provision no doubt reaches the point where consumers begin to cut back their spending – nullifying capital’s ability to keep passing on the costs – first.

But the low-paid spend a much larger portion of their income on non-discretionary things such as food and rent. If the supermarket duopoly in Australia wants to keep passing on rising transport costs through the price of essentials, the low-paid will simply have to wear it. Ditto for rising rental costs when any interest rate rises incentivise landlords to hike rents when (seemingly ever shorter-term) leases expire, as happened to both my sister-in-law and my father-in-laws brother. She is a professional on a reasonable salary but the hike still forced her to move house. He is an old pensioner and was forced to move the whole length of Queensland to find affordable accommodation with relatives.

How much inflation in life’s essentials will the poorest be forced to bear before inflation is tamed I wonder?

” Particularly a problem for taxes that take a longer period to pay, i.e. in the UK many freelances do self reporting and pay their taxes yearly.”

It’s less of a problem with payroll taxes – like, for example, National Insurance. PAYE collections are payable by the 23rd of the month following, and have the lowest collection loss of all the taxes.

Eliminating the separate taxation system for freelancers and requiring them to put their drawings through PAYE – like everybody else – would solve the freelance issue.

But yes spend side auto-stabilisers are best. We’re a long way from a Job Guarantee though.

@Neil Wilson

Thanks Neil

my instinct is to fully support labour in the battle of the mark ups .

Let’s keep wages rising faster than prices.

Governments can interfere with price controls and nationalisations of firms who do not want

To compete in a market they do not control