I have been thinking about the recent inflation trajectory in Japan in the light of…

The Japanese denial story – Part 1

Well, it’s 2022 already and we enter the 18th year of this blog. Regular readers will know that I have studied the Japanese economy in considerable detail over the course of my career and when it experienced one of the largest commercial asset price bubble busts in history in early 1992, the questions I was asking and the data I was looking out were important in framing the way I have done macroeconomics since. I consider Japan to be one of the nations that was early to embrace the madness of neoliberalism – credit binge, wild property speculation then crash – and the first nation to abandon it in favour of more responsible fiscal policy – which given the circumstances required on-going fiscal deficits exceeding 10 per cent of GDP at times. Its policy approach – including the relatively high deficits, the zero interest rate policy of the Bank of Japan, and then the massive bond-buying program by the same, became the target for various New Keynesian macroeconomists (including Krugman) to prophesise doom. Their textbook models predicted the worst – rising interest rates, accelerating inflation, rising bond yields and then government insolvency as bond markets bailed out and the currency plummetted. Nothing like that scenario emerged. Japan was playing out policies that ran counter to the mainstream consensus in the 1990s and beyond and I learned so much from understanding why things happened there as a consequence. This is Part 1 of a two-part discussion about why Japan demonstrates key MMT principles and how those who wish to deny that reality have to invent a parallel-universe version of MMT to make their case.

Japan is an MMT laboratory – like all nations

You can find out about the – Japanese asset price bubble – and its causes and ends.

I am currently writing a book about these events (in a broader perspective of post Bretton Woods history and policy mistakes).

In my reckoning, the Japanese government policy approach provides a number of key lessons, all of which support Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) understandings.

Further, the policy shift we have seen during the pandemic (and was rehearsed during the GFC) is diametric to what mainstream macroeconomists have been advocating for decades as they repeatedly warned that high deficits and public debt levels, and, large-scale central bank bond purchases would lead to disaster.

However, their predictions have been dramatically wrong and provide no meaningful guidance as to the available fiscal space nor the consequences of these policy extremes for interest rates and inflation.

Japan’ experience is illustrative.

It embraced the neoliberal private credit excesses in the 1980s, which caused the 1991-2 property collapse.

The government’s response pushed economic policies to the extreme of conventional limits – continuously high deficits, high public debt, with the Bank of Japan buying much of it.

Mainstream economists predicted rising interest rates and bond yields, accelerating inflation and, inevitable government insolvency.

All predictions failed to materialise.

Japan has maintained low unemployment, low inflation, zero interest rates and strong demand for government debt.

Similar predictions were made during the GFC, when many governments followed the Japanese example.

The predictions failed again because the underlying economic theory is wrong.

Austerity-obsessed governments, applying that flawed theory, forced their nations to endure slower output and productivity growth, elevated and persistent unemployment and underemployment, flat wages growth, and rising inequality.

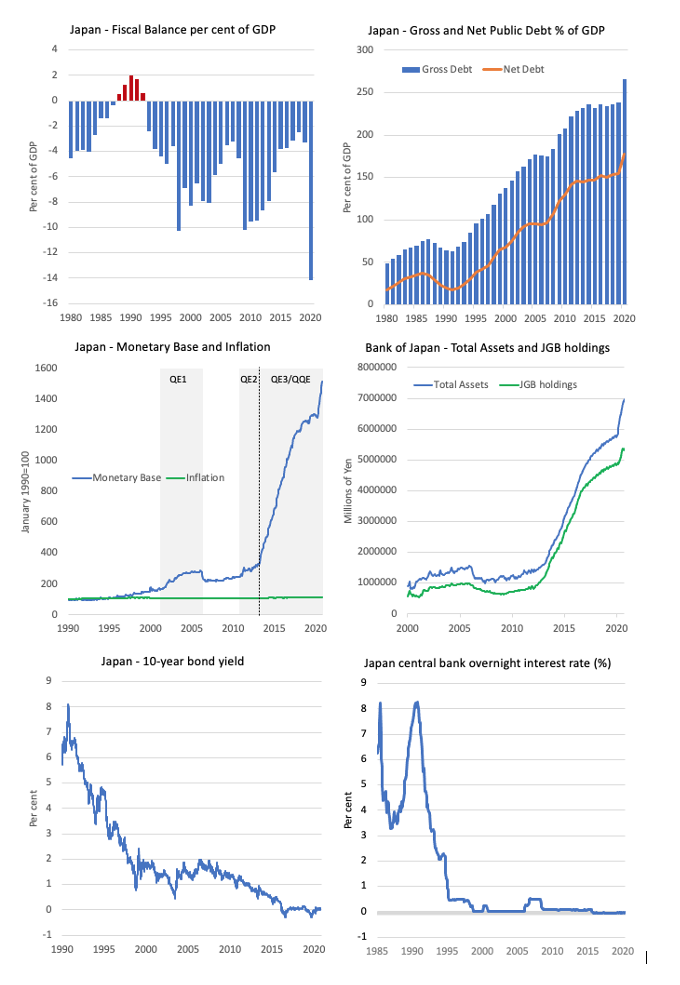

The following graph provides a snapshot of some of the key policy variables and targets since the 1980s.

No mainstream macroeconomist can explain these graphs and remain consistent with what they teach their students, write in Op Eds, write in published research, and tell government policy makers as paid consultants.

MMT has consistently advocated a return to fiscal dominance and disabuses us of the claims that fiscal deficits are to be avoided.

MMT defines fiscal space in functional terms, in relation to the available real productive resources, rather than focusing on irrelevant questions of government solvency.

As far as I am concerned Japan demonstrates what happens when macroeconomic policies are pushed well into the territory that mainstream economists claim guarantees disaster.

And what happens is not what the mainstream predict.

So Japan has been an important case study which is why I maintain close relationships with Japanese researchers and, Covid willing, will be taking up a position at Kyoto University a bit later in 2022.

But with the rising awareness of our work – Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – mainstream economists are lining up to deny that Japan teaches us anything about the way governments should be conducting policy.

The latest attempt at this approach came in an article by American-based Japanese economist Takatoshi Ito – Does Japan Vindicate Modern Monetary Theory? (December 22, 2021).

The no free lunch argument

First, he argues that the high public debt that “the Japanese government has amassed” has not triggered “higher borrowing costs or inflation” but because:

… there is no such thing as a free lunch … it is future generations who will be left with the bill.

He acknowledges that the shift to very aggressive fiscal policies (GFC then pandemic) has not provoked any financial crisis “because government bond yields have been so low for so long.”

He also knows that the central banks have been able to control yields on government debt whenever they wanted through their various bond-buying programs.

Okay, so that is progress.

The imaginary MMT argument

Takatoshi Ito then puts his conjecture about MMT or what he claims is MMT:

Advocates of MMT contend that as long as debt is denominated in a country’s own currency, there is no reason to fear a fiscal crisis, because a default cannot happen. Any withdrawal of fiscal stimulus therefore should be gradual. And in the meantime, new issues of public debt can be used to fund infrastructure investments, income-support programs, and other items on progressives’ agenda, provided that the inflation rate remains below the central bank’s target (generally around 2%).

Is this an accurate description of what MMT economists say?

In part, yes.

There is no reason to fear a fiscal crisis because the currency-issuer can meet any of liabilities that are denominated in its own currency – clearly that is definitional.

They issue the currency – they can expand it at will.

So if we are defining a fiscal crisis to occur when the government runs out of money then that is impossible for a currency-issuing nation.

The clue is that the debt issuance is not funding the spending.

It is matching it by definition of the way the auctions are organised by the various debt management authorities that governments have created.

But matching is not causation.

The original and current MMT position is that such governments do not need to issue the ‘matching’ debt and should cease to do so.

Anyone purporting to be an MMT advocate who argues otherwise is not being true to our work.

So you can see that the second part of the Ito’s quote about – new issues of public debt being “used to fund” various things that might or might not be desirable is his invention about what MMT says.

We do not advocate that position and never have.

So then the link between the inflation rate and the central bank’s target rate being some sort of MMT ratio to trigger fiscal action (including debt issuance) is similarly spurious.

Thus this Op Ed is not a good start for a critique of MMT.

Like many similar critiques – we get imaginary MMT developed by the author and then shot down.

Real MMT evades scrutiny therefore – why? – because otherwise the author would not be able to make his/her/whatever case.

The Japan is different argument

Takatoshi Ito is correct to say that:

MMT’s boosters cite Japan as proof of concept.

However, the use of the term ‘boosters’ is an attempt to demean.

Boosters are like carnival barkers or shoddy car sales people.

I don’t say New Keynesian boosters.

I say New Keynesian economists.

But he is correct in saying that people like yours truly do consider Japan to demonstrate what does and does not happen when policies are pushed beyond conventional limits.

And I qualify that by noting that there are nuances relating to economic structure and the like that any case study analysis has to take into account.

So what might apply to Japan, as an advanced industrialised nation, may not turn out the same way for a impoverished African nation with very little export potential.

What will apply though is that the monetary and fiscal institutions will work broadly in the same way.

Why does Takatoshi Ito think we should not use Japan as an example?

After acknowledging that the gross “debt-to-GDP ratio (including both central and local government) is above 250%” and that long-term bond yields have

“remained at around zero throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, and its average inflation rate has barely exceeded zero for 20 years” and that “Annual new bond issues and soaring debt levels have not had any apparent impact on borrowing costs”, he thinks there are particular Japanese circumstances that prevent us generalising from this experience.

Which are?

– “Japanese government bonds are issued in yen, and almost all are held by Japanese residents, both directly and indirectly through financial institutions and the central bank.”

– “This makes Japan quite different than the US, whose Treasury bonds are held by investors worldwide.”

Both points are illustrative of the way a mainstream economist thinks.

Think about these two statements.

First, neither the US nor Japanese governments issue bonds in foreign currencies.

So there is no point trying to make a difference between the two as if it matters.

Second, does it matter who holds the local currency bonds?

Well, in some cases it might, but we need to first understand what it means for a foreigner to hold a US government bond (as an example).

Take the popular argument that China is funding US government spending and shifts in geopolitics will cause the US grief when China calls in the piper.

China can only do what the Americans and everyone else it trades with allow them to do.

They cannot sell a penny’s worth of output in USD and therefore accumulate the USD which they then use to buy US treasury bonds if the US citizens didn’t buy their stuff.

Presumably, people buy imported goods made in China instead of locally-made goods (which are more expensive) because they perceive it is their best interests to do so.

There is often a curious inconsistency among those who advocate free markets.

They hate government involvement in the economy yet propose complex regulative structures (for example, tariffs) which would increase government control on resource allocation and, not to mention it, force citizens (against their will) to purchase goods and services they reject in an open comparison (on price and whatever other characteristics).

Many economists do not fully understand how to interpret the balance of payments in a fiat monetary system.

For example, most will associate the rise in the current account deficit (exports less than imports plus net invisibles) with an outflow of capital.

They then argue that the only way the US (if we use it as an example) can counter this is if US financial institutions borrow from abroad.

They then assume that this is a problem because it means, allegedly, that the US nation is “living beyond its means”.

It it true that the higher the level of US foreign debt, the more its economy becomes linked to changing conditions in international credit markets.

But the way this situation is usually constructed is dubious.

First, exports are a cost – a nation has to give something real to foreigners that it we could use domestically – so there is an opportunity cost involved in exports.

Second, imports are a benefit – they represent foreigners giving a nation something real that they could use themselves but which the local economy will benefit from having.

The opportunity cost is all theirs!

Thus, on balance, if a nation can persuade foreigners to send more ships filled with things than it has to send in return (net export deficit) then that is a net benefit to the local economy.

I am abstracting from all the arguments (valid mostly!) that says we cannot measure welfare in a material way.

I know all the arguments that support that position and largely agree with them.

So how can we have a situation where foreigners are giving up more real things than they get from the local economy (in a macroeconommic sense)?

The answer lies in the fact that the local nation’s current account deficit “finances” the desire of foreigners to accumulate net financial claims denominated in the local currency.

Think about that carefully.

The standard conception is exactly the opposite – that the foreigners finance the local economy’s profligate spending patterns.

In fact, the local trade deficit allows the foreigners to accumulate these financial assets (claims on the local economy).

The local economy gains in real terms – more ships full coming in than leave – and foreigners achieve their desired financial portfolio.

So in general that seems like a good outcome for all.

The problem is that if the foreigners change their desire to accumulate financial assets in the local currency then they will become unwilling to allow the “real terms of trade” (ships going and coming with real things) to remain in the local nation’s favour.

Then the local economy has to adjust its export and import behaviour accordingly. If this transition is sudden then some disruptions can occur.

In general, these adjustments are not sudden.

Conclusion

In Part 2, I will trace through the transactions that reveal what is going on with respect to foreign bond purchases.

And then we will discuss the inflation story, the kids are being screwed story and more.

Coming tomorrow.

Happy 2022 – and don’t forget to watch Don’t Look Up.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

What about invisibles within current account deficits?

I get the idea that the day that ship arrives filled with things other people have made- well that’s great for your local economy in terms of real products. At least at first. But ten years later when all your local producers have gone out of business, is that still good?

Recent example might be these computer chips that we can’t make cars without, apparently. Seems to have affected the US economy and inflation rates quite dramatically. Yes, it is nice when other countries will send us computer chips. But it really is not great when they cannot, and we find ourselves mostly incapable of making them ourselves anymore.

“it is future generations who will be left with the bill.”

Aren’t they also left with the assets with which to pay the bill? Why aggregate one side of the balance sheet, but not the other?

Once you take the MMT position that spending causes taxation, and you do the standard geometric progression that implies, you understand that taxation will match spending to the penny for any positive tax rate.

Imagine a stone skipping across a pond. Every hop is a taxation point. The stone always sinks, which tells us the spending sequence will come to an end, and the number of hops changes, which tells us the effect of higher and lower taxation.

Saving is like watching a video of the hopping stone and pressing the pause button half way along.

Then in the future, the pause button is released, and the hopping continues.

Government debt is the accumulation of lots of videos of hopping stones with their pause buttons pressed. Those videos are passed onto future generations who may release the pause buttons by spending their savings. Are which point the hopping continues and the tax that induces matches the amount of debt.

Government debt isn’t just a store of value, it’s a store of taxation.

MMT reveals that. The mainstream, with their debt and interest obsession, misses it completely.

“Yes, it is nice when other countries will send us computer chips. But it really is not great when they cannot”

How is that different from having one supplier in Alabama, who sends out the computer chips and then suddenly they cannot because they were making so much money they forgot to invest in new production plant?

The issue isn’t foreign production. The issue is that nobody considered diversity of supply and excess capacity to produce – which is required so that markets function properly. It’s just another example of how private provision tend towards efficiency at the expense of resilience, which makes them brittle and incapable of responding to changing circumstances.

It’s a failure of public authorities to manage the market so that monopolies don’t arise. Those can occur offshore as well as on.

Once you understand that private markets trade resilience for financial efficiency, then market authorities have to counter that with public interventions to maintain an orderly market.

I don’t think I disagree with what you wrote here Neil. But your points about the brittleness of supply chains and “market authorities have to counter that with public interventions to maintain an orderly market” get lost in the story Warren Mosler tells about how it is all wonderful that the ‘they’ are sending ‘us’ real things for less than we send them. Bill does this also to a lesser extent sometimes.

I think I pointed out an instance where this can come back and cause a problem. Not that I know anything about making computer chips or automobiles. Or much about Alabama for that matter.

” Their textbook models predicted the worst – rising interest rates, accelerating inflation, rising bond yields and then government insolvency as bond markets bailed out and the currency plummetted.”

Now playing out in Sri Lanka.

It would be interesting to run an MMT-oriented case study in what went wrong there; massive debt denominated in foreign currencies, reduction in productive capacity and tourist business due to pandemic, and badly planned farming reforms, most likely.

But, perhaps more importantly, what needs to be done to fix it.

Happy New Year to Bill, and regular commenters.

@MrShigemitsu

“Now playing out in Sri Lanka”:

At least some of Shi Lanka’s borrowing is in foreign currency. In this sense Sri Lanka is only partially monetarily sovereign. As is, for example Italy (which borrows in a foreign currency, the Euro). So, Shi Lanka is different from Japan which, is monetarily sovereign and borrows in Yen.

“Sri Lanka Development Bonds (SLDBs) are debt instruments denominated in US Dollars issued by the Government of Sri Lanka in terms of the Foreign Loans Act, No.29 of 1957. Repayment is guaranteed by the Government of Sri Lanka.”

“But ten years later when all your local producers have gone out of business, is that still good? ”

If Country A is running an export surplus with Country B and acquiring B’s financial assets, it is not in A’s interest if B’s financial assets become worthless because B has severally reduced productive capacity?

@Tim Borer,

Well quite.

That’s why I mentioned “massive debt denominated in foreign currencies”!

Also of interest though was the sudden, forced implementation of organic farming last May, with the prohibition of chemical fertilisers, eventually abandoned six months later after a shortage of food (= Zim style production capacity decline).

Sri Lanka’s macroeconomy was clearly not led by MMT principles, but I would be interested what the solutions might be to get them out of the mess – though I know one could reply, “Well, if I was going there, I wouldn’t leave from here”!

‘there is no such thing as a free lunch’. Build your economic argument up from the infallibility of a pithy saying.

If exports are a cost and imports a benefit and the desire to accumulate financial assets in Usd is the reason China is a net exporter why are they willing to accumulate financial assets? What are the benefits of this accumulation?

Happy New year Bill,

The more you study it the more It just backs up the geopolitical, US foreign policy agenda.

Because none of the things they say will happen ever happens after you study over 50 years worth of real data. Yet, they keep pushing the false narratives and framing.

Why ?

Because even before the Berlin Wall fell economics was always about control. Control by the leisure class and capital. All you need to do is look at British trade policy under the days of the British Empire it was all about control with the aim of protecting the British ruling class. Why so many countries like Australia, New Zealand, India and Canada were desperate to break free from it.

Back in the day the British economists were promoting false narratives and framing that supported the Empire and on the ground in the countries they conquered never did what the British said they would. Many a war was fought over it. Warren even showed how the British used economics to control workers in foreign countries to produce coffee for the British.

You have to look at it from a geopolitical perspective. Why do the economists who are the leaders of the paradigm support and promote the narratives – that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would lead to disaster. You have to study it from a geopolitical perspective.

Why have China and Japan for example completely ignored the Western paradigm. Why does Japan deny what they are doing. Russia and other countries move away from it after seeing through the geopolitical scam.

For me promoting that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would lead to disaster is all about control. It has to be because when you look at the real data ever since it was introduced it is a fairytale.

If you study how Germany went from a basket case after world war 1 to the economy they had before the start of world war 2 who completely ignored the paradigm it scares the West. To the point that America is now the only country in the West that is allowed to peruse Military Keynesianism.

For me it is as clear as day that the mainstream paradigm is nothing more than a bunch of second hand car salesmen that sell second hand cars for the leisure class. When you read the price of piece by Zach Carter you can see exactly when this became the norm. Keynes knew it As he watched them basterdise his work. He knew which path the leisure class was going to take. It has only taken them 70 years to get there after playing the long game.

There are now thousands of MMT’rs who are not even economists. Just working class people from every walk of life who have never been to Oxbridge who can see clearly that that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would NOT lead to disaster. By simply looking at the real data and the graphs they produce. That alone should be enough to convince everybody that by promoting the high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases myths is geopolitical foreign policy based on controlling countries and keeping them under your influence.

I’ll ask again how do you go from understanding MMT in 1945 and during the war which all countries did. To what we have Today ? You have to understand how things actually work otherwise you couldn’t have done it. The Chicago School that was simply a cupboard at the Pentagon couldn’t have done what they did without understanding MMT completely.

The liberal world order was set up to defeat Russia and the economics paradigm created policies to try and achieve rhat. Neoliberal globalism was created by the paradigm so that the leisure classes in the West could own all the very important assets in the world. See how Rome and the British Empire operated for details. How They absorbed and worked closely with the leisure classes in every country they conquered. Look at how the Nazi’s absorbed and worked closely with the leisure classes in every country they conquered. You will see the early ideas of the Euro taking shape. In each and every example bar none the economics paradigm created was all about control. Based on controlling nation states after you conquered them. Study Cyprus over a 1000 year period and it is fascinating to watch how these different control mechanisms were out in place by different conquers.

American-based Japanese economist Takatoshi Ito is no different to the Roman governor of Britannia or Gaul. Or the British Governor-General of India or Australia who played 5 day test matches of Cricket with the leisure class of both countries. Takatoshi Ito will say and do anything to protect the liberal world order and US foreign policy if it means that Japan remains an ally and not an enemy. Will do nothing to upset the US military bases that surround Japan.

The leisure class know fine well that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would NOT lead to disaster. A baker in Bradford and a postman in Portsmouth that studied MMT knows it. Frank Newman – Former Undersecretary and Deputy Secretary of the U.S. Treasury knew it and everybody Warren spoke to who were part of the leisure class knew how it worked. It is the economists and politicians that are their to spread the myths and keep them alive.

The leisure class have known it for a very long time

Where’s the Money Coming From?” by Stuart Chase, 1943

https://underground.net/wheres-the-money-coming-from-by-stuart-chase-1943/

“IN 1925, Russia had been through a devastating war and a violent internal revolution. Her currency had been destroyed in a runaway price inflation, she was the world’s worst financial risk abroad and she had very little gold. Yet by the end of the first Five Year Plan in 1933, Russia had invested some 60 billion rubles in factories, new cities, cities, hydroelectric developments, armaments, houses, schools. There stood the new plant, ugly and solid. Without it Russia could never have met the onslaught of Hitler’s armies.”

Where did the money come from?

“In 1933 it was freely prophesied that Italy could not invade Ethiopia. She had no credit abroad and almost no gold. The effort would bankrupt her. Italy went ahead, conquered Ethiopia, and emerged without financial collapse.”

Where did the money come from?

“Hitler took over a Germany which was technically bankrupt. It had defaulted on its foreign obligations. When he proposed to build a powerful army, together with all kinds of grandiose public works, he was laughed at in London and New York. Germany was insolvent, and the whole idea was preposterous. The nations of Europe which have trembled under the thunder of panzer divisions know that Hitler built even more terribly than he promised.”

Where did the money come from?

“When Japan began to rattle her sword in the direction of Indo-China and challenge the United States and the British Empire, wiseacres said it was a bluff. The long years of the war in China had reduced the Japanese economy to a bag of bones. She was bankrupt and could not sustain a real fight. Yet she opened a new attack with devastating fury, and with military equipment in planes, tanks, artillery, ships, that was as excellent as it was unexpected.”

Where did the money come from?

“In 1939, the United States Congress declined to appropriate $4 billions for highways, conservation, hospitals, freight cars, in the bitterly contested “lend-spend” bill. It was widely held that the bill would lead to ruin and national bankruptcy. Yet since the fall of France in 1940, Congress has appropriated almost $300 billions for armaments-seventy-five times as much as the lend-spend bill-and a large fraction of it has already gone into tanks and guns. Far from being ruined, our national vitality has never been more vigorous, and great financial moguls assure us that we shall be able to swing the national debt.”

Where did the money come from?

“After the war America will need to maintain full employment, operate its industries at substantial capacity, provide the essentials of life for all its own citizens, and help foreign peoples who are starving and unable to pay for the supplies. There will be a towering political demand for a world delivered from chronic depression. ”

Where will the money come from?

The best part is here:

“It is clear from these examples that what a great nation can “afford” in periods of crisis depends not on its money but on its man power and its goods. Russia, Italy, Germany, Japan, the United States, all used money in the situations mentioned, but money was obviously not the dominant factor. Man power and materials were the dominant factor. Yet at other times, when crisis was not so acute, the money for necessary tasks could not be found. Unemployment, insecurity, want, dragged on. This is a puzzling paradox. At certain times a nation can afford what at other times, with no less money, it cannot afford. At certain times we are afraid of national bankruptcy, and at other times we give it hardly a thought. ”

Using the MMT lens – The Question then becomes IF the leisure class know fine well that that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would NOT lead to disaster. Then why do they use economists and politicians to promote it ?

More importantly – Why does The narrative and framing that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would lead to disaster support The FIRE sectors. Why is it used to support Wall Street, City of London and Frankfurt and place them front and centre on The geopolitical map?

The answer becomes far more interesting and a hell of a lot closer to the truth when the history of capitalism is taken into account. Economics pushed and funded by the capitalist was never about fairness or equality. it was always each and every time about control and stealing real resources from those weaker than themselves. So they could extract rent from them. Today is no different no matter how we wish it was. Same shit different Century.

Citing Adam Tooze´s “Chartbook #34”: “When Stephanie Kelton says that freeing fiscal policy from the deficit myth makes budgetary decision more not less significant, she is absolutely right. When you don’t have artificial and imaginary budgetary constraints to limit debate, when you admit that, as Keynes says, we can afford anything we can actually do, then the question of what we actually do can no longer be handed off to accountants. There are no longer any excuses”.

Comparing a Country to a household is the kind of statement you would expect from an accountant.

So, we must ask accountants to leave macroeonomics and start accounting.

As we say around here: “Every monkey in its branch” (sorry for the trope).

I wish you all a good 2022.

When you take the not so controversial view that the main economic paradigm is based on control and nothing else.

1. Control the threats to the leisure class within in your own borders

2. Control countries after you have invaded them to allow you to steal the real resources.

The MMT lens allows you to Understand that by forcing countries to export their way to growth by imposing austerity on them via various fiscal type rules. Taking their currency sovereignty away from them. Is exactly the same as Alexander the Great invading Babylon and sending the spoils of war back to Greece. Or the British invading India and sending the spices and tea back home to London.

The only difference is instead of invading and sending an army in to do it. Today all you have to do is convince the leisure class in the country you target to play along. Reward them handsomely for doing so allowing them to become the oligarchy they always wanted to be.

The winners of wars are normally the ones that have won the right to run trade deficits.

Japan’s balance of payments current a/c surplus was 3.3% of GDP in 2020. It was between 1% and 5% of GDP in all years 1996-2020 .This contrasts with the US and GB. See:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BN.CAB.XOKA.GD.ZS?end=2020&locations=JP-US-GB-XC&start=1970

.

The guts of Prof. Mitchell’s account here closely agrees with mainstream economists.

He recognises that US trade deficits and corresponding the Japanese and Chinese surpluses are a “problem” for the USA.

.

The “problem” arises because “In fact, the [US] deficit allows foreigners to accumulate [US] financial assets (claims on the [US] economy).”

“Does it matter who holds [USD] bonds? Well, [yes] in some cases”

According to Prof. Mitchell, the “problem” arises because foreigners could well “change their desire to accumulate financial assets in [USD].

When this happens “they will become unwilling to allow the real terms of trade (ships going and coming with real things) to remain in the [USA’s] favour. Then the [USA] economy [will have] to adjust its export and import behaviour accordingly” .

In other words, in the not too distant future the USD may well be forced to depreciate, in which case the USA would be less able to live beyond its means.

.

Prof. Mitchell, correctly believes that “In general, these adjustments are not sudden”.

But panics and crises occur at unpredictable times in all walks of life. What might happen to the USD if ..??

“At least at first. But ten years later when all your local producers have gone out of business, is that still good? ”

Well in the US lately, local producers didn’t “go out of business,” rather, they were put out of business. Somebody pointed this out yesterday in a comment at Naked Capitalism. When the existing industry was shipped off to China, the U.S. Government could have invested big money to lead U.S. Industry into the development of awesome new technology. (DARPA did this.) Brand new industries could have been created, producing unimaginably wonderful products that the world would not do without, and which would have made the world happy to do the U.S.’s routine work.

This didn’t happen. The U.S. government went on a fiscal surplus jag. U.S. business concentrated on low-cost development and devoted its attention to creating financial fiddles to make some peoples’ numbers bigger while other peoples’ numbers got smaller. And that’s what we’re stuck with. It didn’t just happen – it was done.

People read Arnold Toynbee and rhapsodize over the virtues of Creative Minorities. But there’s a catch to being a creative minority; you have to be creative. Not always easy.

@Jv re: ‘why are they (China) willing to accumulate financial assets? What are the benefits of this accumulation? My take on it is

1. Many workers in China may not have a great life as migrant sweatshop labour, but some Chinese are able to use foreign currency to enhance their life. Of course, it isn’t necessary to have a massive trade surplus to do this, but once you direct the economy to export production, things can get out of hand. South African mine-owners, German bosses and previously, British mill owners, also do/did rather better from exports than their workers. 2. What to do with all the workers, of which China has an extraordinary number, no longer needed for agriculture? China certainly needs more people in welfare and education jobs, and given more leisure, but an easier short-term solution is to find them employment in military/security, travel infrastructure, city building and products for export. 3. While European/US colonisation was/is aided by currency control/pegging, China is able to use its accumulated foreign currency to buy up African assets. Seems to me this is rather more important than any amount stored up in US bonds.

A good one Bill I love the real life examples married to your explanations thanks!!

@Patrick B

Regarding the tiresome trope, “there is no free lunch” I retort “what do you call all the lunches laying around unmade when the markets leave labour and real resources unused?” The wastage is scandalous.

Hi Jerry Brown

I’m interested in what can be said about goods crossing borders as to all intents advantageous if you get what you want. David Graeber describes the absence of money and markets in some societies and yet valued things change hands across boundaries. You can read how Neoliberal markets can put buyers in control of price & determine what’s locally produced. Alternatively governments can keep control of price and markets. In its simplicity I don’t have a problem with what Warren Mosler says – it doesn’t in itself limit ones analysis or comprehension of the detail or structure of economies & what trade can become in capitalism as a money economy.

Hello Jim. Here is a trilogy on trade from Bill Mitchell. As always, he makes good points- even if I occasionally don’t agree completely.

As you might determine from the plethora of comments- should you wish to read them.

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=39282

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=39303

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=39420

even under a floating exchange rate, the decision to import more without a matching capability to export more goods or service of the same value can mean one of 2 things.

or the currency will depreciate and so the economy will suffer from losses to the real income (goods and services aka the national economy wil incure costs) or the national economy will become more and more dependent on capital inflows which will put the economy at a risk of ever increasing finanacial instability.

thats why the decision to export more, and thus develop export led specialized industry which will allow for higher disposable income in foreign currency, cannot be seen necessarily as a cost. because our ability to abstain from imports today in such case will allow us to import even more tomorrow without hurting our real income (real benefit). while in such case importing more today and destroying the national economy’s export led industries can be seen as a real cost on the economy since tomorrow the ability of the national economy to import more will take a hit and thus the ability to import more goods and services in the future will be compromised as well.

Jim and Daniel,

It helps if you look at it from the exporters point of view and understand that Savings are an export product. Understand and not completely ignore that when a currency goes down, all the others in the world go UP in relation to it. Nations that rely upon exports (export led nations) start to lose trade – which depresses their own economy.

When a currency falls and imports become more expensive. It is the exporters to your country that suffers and has some difficult choices to make. See Irish exporters after Brexit for details many of which went out of business.

If imports do become more expensive. We all change our spending habits. We do that because we all have a certain amount of disposable income to spend on things every month. We tend to buy cheaper alternatives or buy locally that helps the local economy. As our disposable income no longer allows us to buy the more expensive imports.

If imports become more expensive. Then it is the exporters that have the tough choices to make it they want to keep their market share. The market share they’ve spent years building up in your country.

a) They can cut wages

b) Cut hours worked

c) Sack staff

d) Go bankrupt

e) Reduce their prices

f) A combination of all of the above

If they reduce their prices the floating rate automatically adjusts and the local currency becomes stronger. That stops the fall in the currency.

Here’s 2 links that looks at the problem from the exporters point of view.

It’s the Exporters Stupid

https://new-wayland.com/blog/its-the-exporters-stupid/

Savings Are an Export Product

https://new-wayland.com/blog/savings-are-an-export-product/

If you export to excess you gather foreign currency. You have no choice because there is insufficient imports to swap all your earnings to the local currency.

So how – as a net exporter – do you pay all your staff who want local currency?

Answer: you sell the foreign currency to your bank who then creates the local currency for you in return.

This is obvious when you think about it. Foreign currency is an asset – a loan to a foreign nation. Once the bank has hold of it in the asset column it can just mark up your local currency account and ‘credit’ you with the exchange value.

And this is how net exporters work in aggregate. They hold foreign currency hostage (or foreign currency bonds if they can get them) so they can discount the correct amount of local currency against it. It makes the accounting look good at banks and central banks and has the added advantage of draining domestic circulation abroad making more space for your goods and services exports.

Now think about it in terms of multi-national banks. If I’m banking with HSBC there will be a local branch in Japan and a local branch in the UK. If a Japanese company has an excess of Sterling it needs Yen for, then the local branch in Japan will move the Sterling to its account at the UK branch (HSBC Japan – Sterling Asset a/c) and then mark up the Japanese company’s account in Yen. The Sterling then becomes just an intra-company loan of no significance to the overall accounts. If there is a build up of Yen on the UK side, the bank can do an internal swap to eliminate the currency on both sides and shrink the balance sheet (which reduces the liquidity ratio requirements on both sides).

So if you eliminate interest paid on UK government assets and force foreigners to hold just currency, they will likely continue to hold it within their banking system as the offsetting asset to local currency creation. Because that’s what you have to do to continue being a net exporter in a floating rate currency (the alternative is to get 18 other countries to sign up to use your currency Eurozone style).

They may have to go through a cycle or two of excessively high currency rates (and therefore we have low currency rates) and trade collapses before they get the message. It all depends how astute the foreign politicians are and whether they care about their own economy or some other political end.

Consider what the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth fund owns – just as an example. Shares, property, bonds in Sterling. When it receives the coupons, dividends and rent it then buys more Sterling assets with them. What does that do? It just forces up asset prices in the UK focussing the economy on producing assets, rather than actual stuff.

So the profit outputs go to those who trade assets to those who hoard assets. Also known as ‘rich people’.

Imagine a population where some are looking to move from spending to saving and some are moving from saving to spending. If you have tradeable saving instruments in a forced liquid market then nobody’s behaviour is changed at all. You’re relying entirely upon the idea that the price of saving will change minds ‘at the margins’ and there will be no networked feedback loop between the individuals. In other words you’re assuming advertising and Facebook don’t exist.

If you want to encourage saving,

(i) why do it with an instrument that is permanently tradable in an infinitely liquid market backed by HM Treasury as buyer of last resort?

(ii) why do it with an instrument that can be held by business and banks and gives them a risk free income for doing nothing?

Surely if you wanted to encourage saving for whatever reason you’d do it with five year Granny bonds at National Savings that can only be held by individuals?

Gilts are there so that government can pretend private pensions are private and not a state pension/tax collection system in disguise. Index linked gilts were specifically brought in at the request of the pension industry.

The rest are used as collateralisation instruments in the finance industry which is why, as Bill mentioned in one of his many blog posts, the Australian finance industry begged the government to continue issuing government bonds when Australia was running a surplus. Again this is so that we can pretend that the banking system is private and not a state franchise.

There is, and remains, no need for government bonds. It is just a corporate welfare payment.

Switch yourself around to the point of view of a Chinese producer. Put yourself in their shoes. Then what happens is this.

There is insufficient demand at home to keep your factory going. Just not enough orders coming in. So you either close or you entertain these orders from a foreign nation offering funny green bits of paper that are worthless to you. So you have a word with your local PBC branch and they let you know that they’ll take the funny green bits of paper and give you real money in exchange. And they can even tell you how much real money you’ll get.

That reassures you and off you go producing safe in the knowledge that you’ll get real money for your output which you can spend in the shops in China.

So how does the PBC do that.

Again, put yourself in the shoes of the PBC. In the hands of a bank foreign currency is a loan asset. It’s collateral. What does a bank do with collateral? it discounts it for the local currency.

The transactions are DR Foreign currency assets, CR local factory owner’s deposit account

Now read that again. What has happened?

The bank has gained ownership of a valuable foreign asset *and created local money against it*.

This is how foreign export-led economies maintain circulation of their local money in the face of the drain to savings. They hold foreign currency assets to make the balance sheet look good. It is far, far easier politically to discount against so called ‘hard currency’ than it is against the apparently nebulous ‘taxpayers equity’ asset. Even though functionally it has precisely the same effect – injection of local money into the economy.

Let’s look at Norway again.

You’re an oil producer in Norway and you earn in US dollars. But the Norwegian government taxes you heavily in Krone to avoid a ‘Dutch disease’ issue and to ‘save’ for future generations.

So what happens?

The government pays the tax amount, in Kroner, into the Government Pension Fund using the usual mark up routine. It charges the oil funds the tax amount (as corporate taxes and licence costs). To get the Kroner, the oil company swaps USD for Kroner – effectively with the Pension Fund. The Oil company now has the Kroner and can settle its tax bill.

The Pension Fund now has USD which it uses to buy equities from abroad and that approach drain more USD in income (and Euros, GBP, etc). The fund puts a huge ‘hard asset’ on one side of the national balance sheet which can be discounted quietly by the Norwegian central bank to maintain the circulation of Kroner in the face of the drain to savings. You can do much the same with Denmark – except that the pension funds there are privatised.

Worth thinking about what all of that means with a job guarentee in place as a JG attracts foreign direct investment which helps to keep your currency strong. Creates full employment within your own borders.

There are two parts to the Job Guarantee system. There is the ‘tight’ employment in the standard market (where people are matched to jobs), when that runs out you are left with unemployment (the NAIRU of legend). The Job Guarantee turns that unemployment into ‘loose’ employment (where jobs are matched to people) at a fixed wage. Job Guarantee people are then a more credible threat to the jobs of those in the standard market – because they are working and job ready – than they would be if they were unemployed. That activates the anchor via a dynamic feedback between the ‘tight’ and ‘loose’ labour markets, clearing out the parasite economy while mitigating wage demands in the secondary labour market.

So the way that you manage the variation in net savings is to set taxes a bit higher giving less ‘tight’ employment and more ‘loose’ employment. Then if you get a savings splurge the ‘tight’ employment will increase and the ‘loose’ employment will decrease buffering and anchoring prices in the system. So you build in a margin in the discretionary tax setting and let the Job Guarantee auto-stabiliser do the auto-stabilising.

And remember there is no difference between foreign and domestic Sterling savings. They act in the same way. Trump thought he could treat them differently and why he put tariffs on Chinese goods and all be did was create inflationary pressures within America and made imports more expensive.

One of the ways you can treat foreign and domestic savings differently is by offering granny bonds to the local population and stop issuing government bonds to every one else.

“I think I pointed out an instance where this can come back and cause a problem. ”

Not really. You missed both points.

– market competition has to work which requires excess capacity to supply. That’s standard economics not even MMT argues with. Remember that price control in the MMT view is a battle for market share between quantity expanders, who then eliminate price expanders.

– abroad sends us stuff *in addition* to what we produce ourselves, because by following MMT recommendations we are guaranteed to have full employment.

Whether something is here or abroad is irrelevant, because the analysis looks at institutional entities operating in the denomination – wherever in the world they are located.

Who funds the Chinese exporter?

We have learnt that it actually isn’t the foreign consumer, who just provides otherwise useless foreign currency to the Chinese exporter, but it is instead the People’s Bank of China that pays the exporter with Yuan created out of thin air based on the current currency exchange rate.

The PBofC could one day decide that all these foreign currency holdings are of little value and alternatively inspect the Chinese exporters goods as being fit for purpose and then dump these goods into the Pacific Ocean. The exporter could still receive the same quantity of Yuan and therefore remains happy and the Chinese government would perhaps remain happy that worthy industrial jobs are still being created along with additional industrial capacity and an associated comprehensive supply chain which is also good for military production if needed; or to meet the needs of Chinese consumers if desired.

But perhaps the Chinese government would not be happy with this ‘Pacific dumping’ arrangement as the Western and other global consumer nations would have retained their productive capacity as the global consumers would instead have needed to source their purchased goods and services locally.

China may well be net exporting to the world at a material cost to them as per MMT thinking but China is ALSO rapidly gaining an overwhelming productive capacity advantage, a technological advantage in many important areas, a potentially overwhelming military production advantage and a geopolitical advantage over the rest of the world and the West in particular that is far more significant in absolute and relative terms to that which Nazi Germany attained prior and during WW2.

The substantial holdings of foreign currency reserves by the People’s Bank of China are mostly just earning a low rate of interest but these reserves are also being used to buy up foreign assets, to extract rents from foreign citizens, to acquire strategically located military facilities and to create favourable for China debt traps in many vulnerable developing countries.

For example the AU$9.7 billion sale in 2016 of the Port of Melbourne 50 year lease to mainly Chinese investors which will increase the cost of imports for local consumers as well as increase costs for local exporters further reducing their competitiveness, when alternatively in a non neoliberal world the federal government using the RBA could instead have provided the same funds to the Victorian government at no real cost to retire some of their debts. Of course China is not alone in these rent extracting and other hegemonic arrangements and major US, European and other Asian financial institutions are doing much the same for their ‘leisure classes’. Australia in my view has ‘out banana republiced’ most other banana republics in selling off local assets to foreign rent seekers leaving the populace to pay ever more rents which reduces material living standards.

I don’t trust the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party to act in the best interests of any foreigners or even in the best interests of China’s citizens, or to not actively pursue grand strategies of great harm to the people of foreign nations and I can see many parallels with the rise of Fascism in Germany.

Our worst enemies are however our own rent seeking bankers, financiers and other local ‘leisure classes’, and their propagandists and foot soldiers – the mainstream economists, politicians, bureaucrats, lobbyists, mainstream media and other ‘advisors’ that knowingly lie and betray us; that fail to adequately address the hegemonic geopolitical strategies of China, Russia, the United States of America and even the EU by varying degrees, and that ultimately by design or by default seek to enslave most of us as serfs and that also care little if through their actions in imposing the scourge of global neoliberalism and de-industrialisation lead the world into another potentially even more destructive world war.

A knowledge of MMT informs us that we can instead avoid the scourge of neoliberalism, ensure full employment, set in place strategies that will improve human welfare for all and increase our resilience to the major environmental, economic and geopolitical challenges we now face.

jv, I don’t think anyone answered your very good question.

I believe a big part of the answer is that the Chinese government wants to develop domestic industry that is competitive internationally. So the Chinese government keeps the yuan undervalued so its exports are competitive while its industrial base develops world class expertise.

The way to keep the yuan undervalued is to print a bunch and use them to buy dollars on the forex markets. This makes yuan plentiful and cheap, and dollars relatively scarce and expensive.

The Chinese government also for good reasons wants to keep unemployment low. When you export goods you’re also importing, in a very real sense, jobs. Undervalued currency helps there too.

“Not really. You missed both points.”

I didn’t miss your points Neil. You are the one who posits some monopoly supplier of computer chips in Alabama- as if I argued such a situation would be ideal. And since when does ‘market competition has to work?’ Plenty of examples where it has not.

And ‘abroad’ sends us stuff in addition to what we produce ourselves- well the problem arises when you no longer have the facilities and expertise and supply chains to ‘produce ourselves’. I’m all for the Job Guarantee but imagining the people on it will suddenly become able to produce computer chip factories and staff them is a stretch.

Notice how poor OPEC is by selling us all that oil.