Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

The ECB is facing a crisis – rising inflation and risk of Member State insolvency – how to make a problem

The Eurozone continues to stumble on, held together by the vast bond-buying program of the ECB, which has saved several Member States from insolvency over the last several years. While all the talk at present has been about what to do about the punitive and unworkable fiscal rules in a post-pandemic (when will that be?) period, when the emergency waivers of the Excessive Deficit Mechanism procedures are withdrawn, the reality is that under the current architecture, the only thing that keeps the currency union intact is the ECB acting outside of the legal structures set down by the treaties. Yes, I know full well that the elites have massaged the public into believing that there is no breach of the no bailout clauses, but the reality is different. The ECB is (indirectly) funding Member State fiscal deficits through its massive asset purchasing programs, the two relevant ones being the PSPP and the PEPP. And ever since they introduced the Securities Market Program (SMP) in May 2010 they have been providing funding to Member States to allow them to run fiscal deficits while maintaining low bond yields. With the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) scheduled to end in March 2022, the fears are growing that Italy will be the first Member State to succumb to the bond markets – the yields on debt will rise because the investors appreciate the credit risk and will know they cannot offload as much debt onto the ECB in the secondary markets. The fact that these fears are becoming more widespread should tell you that the role of the ECB is exactly what I say it is rather than the ‘maintaining order in investment markets’ spin that the ECB runs as the smokescreen.

The ECB is now approaching a crisis situation.

With the inflation rate (currently at 4.9 per cent per annum) well above its definition of price stability (2 per cent) it is being pressured to abandon its various bond purchasing programs.

This is based on the mainstream argument that the liquidity pumped into the reserve accounts of banks via the various bond-buying programs is inflationary – the so-called ‘printing money’ myth.

The ECB is full of economists who believe that sort of fiction.

To some extent the ECB has reduced pressure on itself to act by adopting a symmetric approach to their price stability target.

The US Federal Reserve led the way in this respect in August 2020 when it effectively abandoned the NAIRU-forward looking approach to monetary policy setting and instead said it would tolerate temporary deviations in inflation from its price stability target as long as the unemployment rate was still falling.

They had reprioritised policy to target the irreducible minimum unemployment rate instead of using unemployment to discipline price pressures that they

‘expected’ to occur, even if the pressures were not evident in the data.

That was a massive shift in thinking by the central bank and represented a rejection of the mainstream NAIRU approach that has dominated policy setting for 3 or more decades.

So the ECB can always say the current inflation is transitory (an assessment that I agree with) and that they will continue to support the real economy.

Their dilemma is, of course, that they know full well, even if a host of mainstream economists like to deny it, that their bond-purchasing programs are the only thing standing between several Member States remaining solvent and having to declare bankruptcy.

Remember the 19 Member States in the monetary union, effectively use a foreign currency having surrendered their sovereignty when they entered the eurozone at the turn of the century (for some and later for others).

That means that they have to rely on taxation revenue to spend in euros and if they want to spend more than that tax revenue, then they have to convince the bond markets to loan them euros.

The bond markets know each Member State has credit risk, which means the governments can run out of euros if they cannot get them from the markets.

And as deficits rise to deal with the pandemic, that risk rises and the bond markets demand higher yields on the loans they extend to the governments to offset the rising risk of default.

At some point the yields would get too high and the government would not be able to continue without some sort of default.

Enter the ECB.

They can ensure the bond markets keep extending loans to the Member States by making it clear they will purchase the debt once bought by the private investors.

The private investors thus know they can tender for the debt, onsell it to the ECB for a capital gain and so the fiscal deficits of the Member States continue to receive the euros they need.

So the dilemma for the ECB is that they cannot really abandon these bond-buying programs no matter how much pressure they are under.

And the programs have been massive funding most of the increase in fiscal deficits since the beginning of the pandemic.

If the ECB abandons the programs, then several Member States – such as Italy – will immediately face insolvency and/or the need to invoke harsh austerity.

It is an ugly prospect.

PSPP and PEPP update

On March 18, 2020, the ECB press release – ECB announces €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) – announced an extra public and private bond buying program.

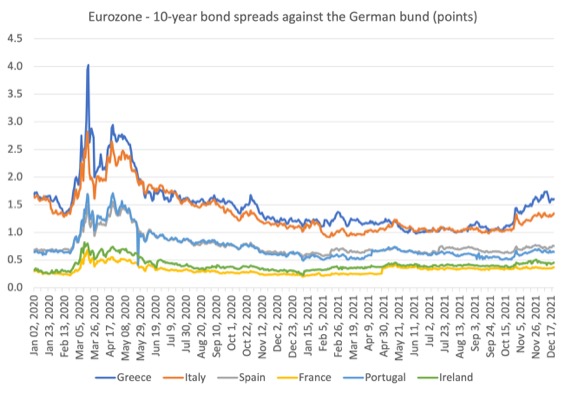

The following graph shows the 10-year government bond spreads against the German bund (percentage points) since the beginning of 2020 up until December 22, 2021 and explains the timing of the ECB’s announcement.

A localised peak in the spreads occurred on March 18, 2020 (for Greece) and March 17, 2020 (for the other nations shown).

Just like during the GFC, the ECB responded to the rising spreads, which would have been catastrophic for the Member Nations in question had they been allowed to be driven by the private bond markets, by increasing its purchases of government bonds.

The PEPP differered from the existing Public Sector Purchasing Program (PSPP), in that, it included Greece for the first time, and so the spread on the Greek 10-year bond quickly followed the downward path of the other Member States.

It also differed because it allowed the ECB to break with the stricter rules governming the PSPP, in particular that the bonds purchased from any country had to be in proportion (with ceilings) to the so-called capital key (the Member State contributions to total ECB capital)

But I think this graph makes it clear that the ECB was able to quickly manipulate the yield spreads.

These spreads are managed by the ECB through its bond-buying programs as I have explained many times before.

How does it do that?

By purchasing large quantities of government debt in the secondary bond market (which is where open trading of these assets occurs after the primary issue has finished), the ECB boosts demand for the assets, which drives up their prices.

The yields are inverse to the price of the bonds and so the increased demand pushed down yields.

To understand this, imagine there is a 10-year bond worth $100 that was issued with a coupon (yield) of 10 per cent. That financial asset requires the government to pay $10 per year for 10 years and then redeem the bond for $100 at the end of the 10-year period.

These sorts of bonds are called fixed income assets because the $10 per year doesn’t change with the current interest rates.

But imagine that the bond price is driven up to say $110 in the secondary trading, then an annual return of $10 will imply a lower yield than before.

Why?

When the bond was worth $100, the fixed annual income of $10 was a yield of 10 per cent. Now, the $10 flow each year is yielding less in relation to the current bond price of $110.

You can also see that the ECB has also managed the spreads in according with the pre-crisis relativities, which is what Isabel Schnabel referred to as their assessment of the “different fundamentals” – largely, credit risk.

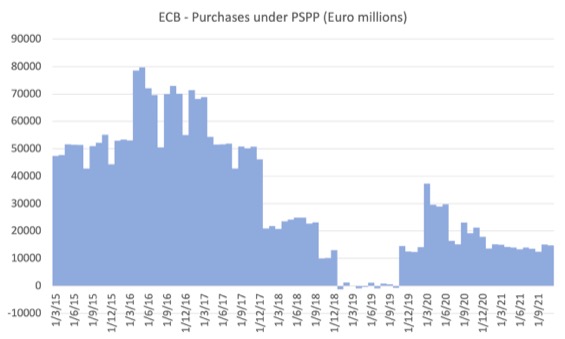

The ECB now has several asset buying programs in place.

The long-standing public sector purchase programme (PSPP) (began on March 9, 2015) buys up various government bonds in the Euro area.

The ECB say that:

Since December 2018 government bonds and recognised agencies make up around 90% of the total Eurosystem portfolio, while securities issued by international organisations and multilateral development banks account for around 10%. These proportions will continue to guide the net purchases.

As at May 22, 2020, the ECB had purchased 2,216,852 million euros worth of bonds under the PSPP. The can loan some of these assets back to the markets “to support liquidty and collateral availability”, which is the way they get around the Treaty no bail-out clauses.

The reality is that the ECB is funding significant proportions of Euro Member State fiscal deficits and without these programs, several countries would have already gone broke.

In their – Public sector purchase programme (PSPP) – Questions & Answers (updated April 2, 2020) – we learn that from November 1, 2019, the ECB committed to monthly bond purchases under its Asset Purchase Program (APP), which includes the PSPP, to the value of “€20 billion.”

The ECB provides a time series of the – Cumulative purchase breakdowns under the PSP.

The following graph shows the entire history of the program since March 2015 up until November 2021.

You can see they had to go hard in March 2020 as the bond markets started to demand higher yields. Once the ECB had controlled the spreads, they were able to maintain a lower level of purchases under this program.

They introduced the PEPP on top of the existing PSPP in March 2020.

The problem with the PSPP was that the ECB could not hold more than a certain proportion of each Member States debt and that those limits would have been exceeded in this crisis given its scale.

They could have just abandoned those voluntary limits but that would have forced them to make admissions about what they were actually doing, even though it was clear for all to see.

So, instead, they they chose to create a new, more flexible program called the – Pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP).

The ECB explained the difference between the PSPP and the PEPP programs in this document (April 2, 2020) – Pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) Questions & Answers.

Purchases began on March 26, 2020.

To the end of November 2021, the ECB has purchased a cumulative total of 1,548,231 million euros worth of government bonds.

Italy facing renewed crisis

The pandemic has not been kind to Italy.

To support households and firms, the Italian deficits have risen as has its public debt to GDP ratio (from 134.8 per cent in 2019 to around 155 per cent in 2021).

Last year, the deficit was 9.5 per cent of GDP, which is the highest level since the early 1990s, when the recession had a massive negative impact on the Italian economy.

We expect, based on Italian government estimates that the deficit in 2021 will rise to 11.8 per cent of GDP.

Earlier in 2021, it has estimated the deficit would be just 8.8 per cent, but, such has been the deterioration in the situation, that the fiscal support had to be increased.

The Italian government has been able to fund those deficits largely because of the PSPP and PEPP conducted by the ECB.

If the ECB was to taper and subsequently abandon the PEPP in March 2022, as it has suggested then Italy would face rising yields and eventually not be able to fund its deficits.

That prospect would intersect with an economy that was struggling to recover from the pandemic, and, was already stagnating.

Italy is not Greece.

The European Commission could eviscerate Greece because it is small relative to the overall EU economy.

Not so Italy.

If austerity was imposed on Italy to reduce the deficit (as bond yields rose) and/or Italy considered defaulting on its debt then the whole monetary union would be threatened.

The EU cannot afford to let Italy stumble.

The ECB knows this and so any talk of the PEPP being abandoned is dangerous because of the functional role it plays in maintaining Member State solvency.

Some people are calling this a ‘doom loop’.

I have consistently made this point.

The inherent architecture of the money union predicates it to crisis.

The ECB has to ‘break the law’ for the union to survive.

Fiddling around the edges of the fiscal rules will not cut it.

The problem is the euro!

Conclusion

The dysfunctional architecture of the Eurozone continues to amaze.

It also puts the ECB in a bind.

I don’t expect it will withdraw its bond-buying programs any time soon irrespective of the course of inflation.

It simply cannot unless it wants to send a few Member States broke and take the political consequences.

What a crazy system!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“The ECB has to ‘break the law’ for the union to survive.”

Is it for the union to survive, or the ECB to survive?

I mention this because a similar event happened with the Bank of England when it started up in 1694. It’s charter limited it to issuing £1.5m of bills, but events of the following two years forced it to start issuing ‘running cash notes’ which allowed it to purchase further government debt technically outside its remit.

This was noted in a broadsheet called “The Mint and the Exchequer United” in 1696.

It seems that reality forces government debt discounters to issue more to keep the show on the road, and the written law has to catch up and retroactively fix that at some later date. I suspect we’ll see that with the ECB in due course.

Morning,

A couple of questions to those in the know..

1. That means that they have to rely on taxation revenue to spend in euros and if they want to spend more than that tax revenue, then they have to convince the bond markets to loan them euros.

2. Last year, the deficit was 9.5 per cent of GDP, which is the highest level since the early 1990s, when the recession had a massive negative impact on the Italian economy.We expect, based on Italian government estimates that the deficit in 2021 will rise to 11.8 per cent of GDP.

How do they work this out ? How do they know how many taxes were collected from the spending in each country and thus what size the deficit is ?

When both government spending and tax collection in each country flows across borders. Scotland as it is has the exact same problem to the point that nobody really knows what Scotland’s budget deficit is.

The government instructs the central bank to credit a nurses, policeman and fireman account with their wages. They all pay their tax then the nurse goes to Blackpool on a hen night. The policeman goes to Cardiff to watch the rugby. The Fireman goes to Northern Ireland to visit family. When they are in Blackpool, Cardiff and Northern Ireland they spend all of their wages.

Businesses in Blackpool, Cardiff and Northern Ireland now have the funds from Scottish government spending and they pay their tax from that income. At this point the whole thing has broken down the taxes have been collected in 3 different countries and the Scottish government spending has flowed across borders.

Same thing would happen if the Scottish government used the private sector to build a motorway with a contractor based in another country. Both the spending and tax collection flows across borders.

It gets worse if these businesses after they have paid their tax then spend their income across borders again. the Nightclub the policeman was in, in Cardiff buys their beer from a brewer in London.

Not only is it impossible to calculate the budget deficit and how many taxes were collected from that spending and put a figure on it for Scotland. Then the tax revenue within Scotland’s border becomes a lottery and has nothing to do with how much money Scotland actually spent.

So how do they work this out in the Eurozone that suffers from the same problem ?

No wonder they force the smaller countries to export their way to growth and discourage imports from abroad by making the countries live with 3% deficit rules. Open up their borders to mass tourism providing low wages and Spain begs Tourists from other Euro using countries to come to their shores. They have to get their hands on Euros somehow in order to increase their tax take within their own border in order to spend more and borrow less.

What a mess. How on earth could any country sign up to this ?

The figures in Italy and the other Eurozone countries must be complete nonsense like the Scottish budget deficit. The difference is Scotland doesn’t need to come up with never ending ways to unbalance their own economy just to get their hands on £’s in order to spend, or are at the mercy of the bond vigilantes. Well unless the SNP get their way that is. Then Scotland will become part of this madness.

If you are a smaller country that always relied on imports from outside the Eurozone with very little tourism or ways of getting the Euro. By the time the Sith and Lord Palpatine are finished with you after merging you into the Blob. You might as well change the name of your country to rent seeking INC.

So how do they calculate these works of fiction and calculate how many taxes were collected in Italy and Spain from the original spending in Italy and Spain and the other countries?

It’s so important that MMT be expressed in elemental ideas, easily graspable by everyone. Fiat money being like points on a scoreboard is one such idea. So is the distinction between money creators and money users. So is a job guarantee, etc. But I think the most elemental idea of all is a principle expressed by Jesus when talking about the sabbath and the onerous rules and regulations that had been superimposed upon it. “The sabbath was made for man, ” Jesus said, “not man for the sabbath.” With the suggestion that the same is true of the economy, I wish Bill and his readers a merry and meaningful holiday season.

Another clear and didactic insight into the E.U. state of affairs.

@Derek Henry

Im not an expert, but I believe this is not true “When both government spending and tax collection in each country flows across borders.” Both govt spending and taxation are accounted for locally, The deficit/surplus simply being the difference in the treasury account, for a time period. What your post shows is that in a shared currency area, the effect of deficit spending may cross the borders as currency is carried, spent and shows up in the GDP of a neighbour, It also wont show up in the “foreign sector” in a sectoral balances analysis of the “home” country.

The EU is facing a crisis…and Australia is facing a “horror post election budget” (winding back $1 trillion government covid-debt while implementing legislated tax cuts).

Alan Kohler has an (“unlikely”) solution:

https://thenewdaily.com.au/opinion/2021/12/20/alan-kohler-early-election/

“To be clear: The only reason the Coalition is able to say that it’s keeping the taxation to GDP ratio below 23.9 per cent is because it is running huge deficits.

It is budgeting to finance an average of 4 per cent government spending with bonds rather than tax.

Maybe it can get away with that in the 2022 campaign because we’ll still be in pandemic emergency mode, and inclined to forgive deficits, but it won’t be able to do it in 2025 and retain any fiscal credibility – unless of course it persuades the nation on the merits of Modern Monetary Theory, and that deficits don’t matter. (Unlikely)”.

Hi Greg,

“When both government spending and tax collection in each country flows across borders.” Both govt spending and taxation are accounted for locally.

It’s the accounted for locally bit which makes it a lottery Greg because you have no control over the leakage when it comes to collecting taxes. Which is very important if then you need those taxes in order to spend. You become dependent on other countries spending into your zone.

Let’s say you unbalance your economy so much in order to receive more tax revenue from other countries within the zone. As you try to encourage their government spending to flow across into your own country.

If you are Spain during the pandemic what happens when Tourists stop flowing across your borders. When you designed your country to catch Euros that way ?

What happens when austerity is put in place right across the Eurozone and you have unbalanced your economy to catch Euros by encouraging other countries within the zone to spend in your zone ?

What ultimately happens is you end up going to the bond vigilante trough to drink more than you would like and end up borrowing in a currency you can’t issue. That only compounds the problem as you have to collect even more taxes than you normally would just to service the debt. You end up unbalancing your economy even more or even borrowing more to pay off the original debt.

That’s a huge problem – Because, Spending only comes back if you have your own currency. If you use somebody else’s then it leaks into a different banking system. Spain’s spending ends up under the control of the Bundesbank. Similarly Scottish spending ends up under the control of the Bank of England, which is owned and directed by the UK government. As long as that arrangement stays in place, Scotland is owned and directed by the UK government – like any other county council.

That is the key issue with fixed exchange rates. You end up with control of the money under some other entity which you have to follow the directions of.

If Spain became independent then what happens depends upon whether it floats its own currency or not. That is the only way to ensure that the Peso doesn’t leak anywhere. What the size of the government deficit is will still depend upon how many people want to net save in the Peso.

Foreigners will save the peso if they want to sell to Spain more things than they want to buy from Spain. If Spain floated the Peso. The floating rate would make sure that export+foreign savings = imports.

Spain can tax it because it is the Peso, and therefore to transfer it to anywhere where it is anything other than inert it would have to go through banks that are licensed by the Spanish authorities to deal in the Peso. They will do as they are told if they want to retain their banking licence.

Why MMT economists always say balance the economy not the budget. That fiscal sustainability is never about the budgets or the debt ratios.

If at some point the interest payments as a % of GDP become so large in an independent Spain and private sector spending is such that there is less non-inflationary room available for other discretionary spending then fine that is what taxation is for – to reduce private spending and/or the government can reduce its own spending somewhat. But before that happens the current account, tax revenue (from higher activity) and saving will be taking up a signifcant part of the adjustment.

But this is just saying that prudent government net spending is limited by the available real resources in the economy left by non-government saving desires.

Yet, in the Eurozone it is all backwards and they can’t stop the leakage across borders when they actually need the revenue to spend.They end up unbalancing their economies so much just to deal with the leakages. That they end up with high unemployment, especially youth unemployment, low wages and under emp!oyment. The bigger Northern countries just end up exporting their unemployment to their smaller Southern neighbours.

Saying the deficit in Italy was 9.5 per cent of GDP, which is the highest level since the early 1990s, when the recession had a massive negative impact on the Italian economy.We expect, based on Italian government estimates that the deficit in 2021 will rise to 11.8 per cent of GDP. Doesn’t explain or tell you that much because of the way the Eurozone has been set up.

Because if it is accounted for locally the 11.8% estimate is equivalent to the Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. A fantasy fairy tale that can’t do anything to stop the baddie in the story the leakage across borders. Unless, Italy of course became independent and floated the Lira and Aslan comes to the rescue.

Aslan balances the Italian economy sets the interest rate to zero, introduces a job guarentee, gets rid of interest rate targeting, reforms their financial sector and pension industry and uses fiscal policy for public purpose and future inflation protection. Introduced an efficient property tax and got rid of many of the non productive compliance costs within the economy by introducing fewer and more effective taxes. That are already baked into the system that automatically catch rising wages and prices. Along with a skills based immigration policy.

Italy has a happy ending freeing itself from the 4 prisons. That the Sith and Lord Palpatine call the 4 freedoms.

If Scotland was independent with its own currency and the nurse goes to Blackpool on a hen night The policeman goes to Cardiff to watch the rugby. The Fireman goes to Northern Ireland to visit family.

All of them would have to visit a bureau de exchange at some point. To try and make sure the Scottish government spending will come back eventually.

Dear Derek Henry (at 2021/12/24 at 1:28 pm)

You wrote:

Perhaps back in pre-1966 times, before Barclays released the first credit card in the UK.

Now, it is almost certain that none of these workers would have to visit any foreign exchange office while doing what you suggest in various parts of the UK (minus Scotland).

The forex part would be done via the payments systems on their behalf. They might be hit with a charge on their statements though.

best wishes

bill

Aye, same thing Bill.

” at some point ”

The exchange would have to take place at some point, as soon as I put my card in the hole in the wall in Blackpool, Cardiff and Northern Ireland. Or when I pass my debit card over the counter. I’m Charged on the street instead of inside a travel agent.

If we go to Europe now we will still visit a bureau de exchange to get a few Euros so we have some when we arrive. That’s if there are none sitting in the back of the drawer from a previous visit. Most people will have Euros sitting in a drawer at home. There are still quite a view who prefer the bureau de exchange to using their cars because of card fraud.

Back of the drawer is another leakage across borders. I could have got the Euros in Spain but now I am going to spend them in Germany and they have sat in the drawer for 2 years. Like VW, BMW, Mercedes, Porsche and Lidel and all the other Germany companies that set up shop in Spain to steal some of Spain’s aggregate demand. That ultimately leads to Germany exporting their unemployment to Spain. Forces Spain to keep going back to drink from the bond vigilante fountain.

Made it so much easier for the leisure class in Greece to escape with their capital.

Today, if I go to England with Scottish pound notes there are very few places that accept them. So when I travel down South I have to swap my Scottish pound notes for English pound notes. Crazy I know but that’s what happens.

One thing that really surprised me after marrying a German was just how different European holiday destination resorts are. You have places were the Germans go and the British go on the same islands in Spain. The German resorts are far superior to the British ones, both the hotels and food are of a much higher standard and quality including the shopping malls. The difference is that stark that whenever we are going to go anywhere in Europe now I ask my wife where do the Germans go. That’s where we book.

Take Fuerteventura for example the German enclave is Costa Calma. The standard is so much higher than anywhere else on the Island. They will not hand over their Euros unless their expectations are met. Yes, you can find a few better on the Island if you pay double the price. All the Islands are the same € for € the German enclaves are of a higher standard and demand a certain level of service and quality of food.

You could say the same about the Americans in South America and the Caribbean. They just love to get their hands on the $ down there. If they need to go the extra mile and offer a better standard of service and better quality they will do it. In some cases you don’t even need to do the exchange they will accept $’s as payment. Mexico is like that if I remember correctly.

Spain € for € definitely goes the extra mile for the Germans. Croatia and other places that are thinking about joining are starting to set up their tourist industry in the same way. Why my wife finds out where they go and we book there. The quality of the hotel and food and level of service is just so much better.

@Derek Henry

Hi Derek.

The query re determination of the size of the deficit was what I targetted in my response to your first post.

I dont disagree with any of your following points.

I havent seen much about leakage in the MMT literature, but understanding the MMT lens is what allows us to clearly identify the issues you have described. It would suggest this as another reason to retain currency sovereignty.

PS I havent been in the UK since 2004, but back then I had no problems spending notes issued by RBS in England.

Merry Christmas from down under.

“The exchange would have to take place at some point”

That depends upon the asset desires of the bank.

When you go to a bank to exchange your Scottish notes, you could ask for that to be credited to an English bank account. At which point the Scottish notes go in a separate bag – for destruction – with the English bank gaining a credit from the RBS/Clydesdale, etc. You then get new money added to the English bank account, as a discount against that credit from the Scottish bank.

The same would happen with a separate Scottish currency, except that you would no longer get a one-to-one exchange rate. And that’s what happens with US dollars, Euros, etc.

In the Eurozone when you take a note issued by one NCB to an area covered by another NCB, the same happens. You can tell which NCB issued the note via the printer identification code in the serial number.

Foreign Exchange is a bit of a misnomer. It’s more Foreign creation and destruction that sort of balances out because banks are risk averse.

Retail FX is done via money creation. It’s the wholesale asset shuffling of the banks between themselves where the price formation happens.