These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Monetary policy is not effective in dealing with a pandemic – it must support active fiscal policy

It’s Wednesday and I have now settled back into my office after being stuck away from home for 9 weeks as a result of border closures between Victoria and NSW. So I am reverting back to the usual Wednesday pattern of limited writing, although today, the topic is worthy of some extended narrative. Before we get to the swamp blues music segment, I am analysing a speech made by the RBA governor yesterday on the role of monetary policy during a pandemic, whether low interest rates are driving house prices too high, and, what should be done about that. The conclusion is that he supports better use of fiscal policy – sustaining supportive fiscal deficits and dealing with the distortions that are contributing to high housing prices, via amendments to taxation (eliminating incentives for high income earners to buy multiple properties) and public infrastructure policies (more social housing).

Speech by RBA governor illustrates what fiscal and monetary policy do

Yesterday (September 14, 2021), the RBA governor presented a speech to the Anika Foundation – Delta, the Economy and Monetary Policy.

Much of the media attention has been on the projections for the economy, in which the RBA is suggesting that the “has delayed – but not derailed – the recovery of the Australian economy.”

I am guessing that this prediction is fairly sound.

We saw after the big infection wave (mostly in Victoria) last year how quickly the economy recovered. This was mostly due to the tight lockdowns that put a cap on the infections and allowed us to open up fairly quickly in a Covid free state.

I think the evidence from 2020 was clear – there was no trade-off between the economy and the health control.

Early on in the outbreak, the ‘free market’ clan were urging the governments of Australia (federal and state) not to impose lockdowns because they claimed the economy would suffer enduring impacts, which were more costly than allowing people to die. Effectively, that was their message.

They were proven wrong.

The 2021 experience is a little different because the conservative NSW government believed some of that ‘free market’ nonsense and maintained lax quarantine practices and then failed to lockdown hard and quickly enough when the predictable breach from their slack quarantine regime occurred.

Since then the debate has changed to vaccinate rather than suppress.

But, given their penchant for a ‘freedom day’, I am sure the economy will start to recover in the fourth quarter somewhat even as the death rates rise.

However, there is one major difference between this year and last year.

This graph is reproduced from the RBA Bulletin article (June 17, 2021) – COVID-19 Stimulus Payments and the Reserve Bank’s Transactional Banking Services – authored by Jiawen Chen and Kristin Langwasser.

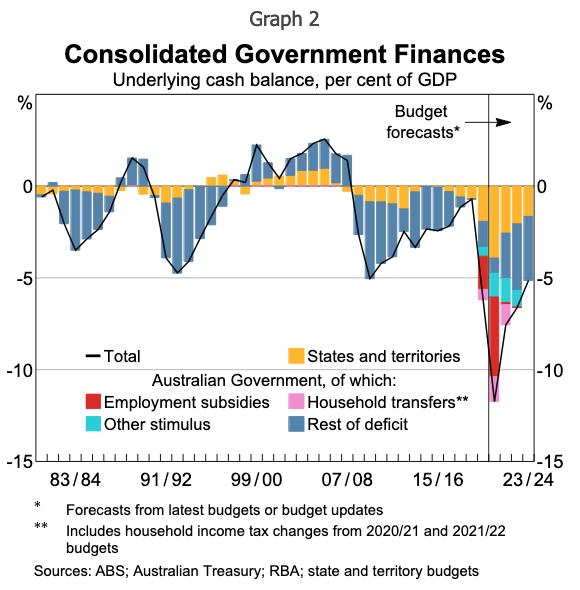

The transition in the fiscal position between last year and this year and beyond is very stark.

Last year, the Federal government spent more than $A90 billion on the JobKeeper wage subsidies (see the red columns) and abandoned that program at the end of March 2021.

This year, and the estimates are somewhat imprecise because it is hard putting the information together from a range of sources, the stimulus the federal level is putting in the system is around $A6 billion.

The yellow bars will be a little different to the graph this year, given the extended lockdowns in NSW and Victoria, that began after the paper was published. Those state governments will be putting in more than the authors would have estimated.

The point is that the federal government is seriously undermining any hope of a rapid recovery.

But it gets darker than that.

The current record virus infections in Sydney, and, now, Melbourne (as a result of leakage from Sydney) are located in the working class, migrant suburbs of the west (Sydney and Melbourne), south-west (Sydney) and north-west (Melbourne).

These workers are typically low-paid and often work in the supply chain sectors and the essential services sector such as cleaning etc.

They are typically workers who will have multiple jobs out of sheer economic need.

Last year, the wage subsidy protected them to a degree and the bonus paid on the unemployment benefit also helped those that did not retain a relationship with their employer (which is what JobKeeper was designed to achieve).

As a result of that protection, these workers were not driven by desperation to go to work when sick or go to work in general.

Now, with all that protection withdrawn, and paltry emergency payments the only assistance on offer, these workers, by necessity, are being forced to disregard their health concerns and go into dangerous work places and mix with the community in dangerous ways.

Result? The virus is continuing to spread.

Last year, the lockdowns worked because the workers who were most vulnerable (and ordinarily unable to ‘work from home’) were protected during the lockdowns and could ‘stay at home’.

This year, no such security is being offered and the results are obvious.

Whether the federal government, which ideologically was against the lockdowns imposed by the states (under their constitutional powers), is now using this fiscal weapon to force the ‘living with Covid’ narrative – a narrative that pleases their pals in the airline industry, in the clubs and bar industry, etc is unknown.

They might just be driven by a stupid ‘sound’ finance mentality.

Either way, the result is a disaster and we are now a relatively high infection rate country after enjoying more than 12 months Covid free.

When we relaxed the lockdown from a zero infection position, it was obvious that people rushed out and spent again and the result was predictable – strong growth.

This time, as the RBA governor noted:

Another source of uncertainty is how Australians will respond to the easing of restrictions, given that the easing is likely to take place with COVID-19 still circulating in the community. This is quite different from our earlier experience, when the number of cases was close to zero, and there was a very quick bounce-back. Whether the same will be the case this time remains to be seen.

I, for one, will be adopting a very cautious approach once the governments relax the lockdown.

The vaccine is not foolproof and the virus will run through the vaccinated population and we do not know yet what that means.

So, I suspect that caution will generalise, except maybe in the younger population.

He later got onto housing prices, which is really the issue that I want to highlight here.

Australian house prices have surged since the pandemic – up 19 per cent.

Regional land prices (outside of the big cities) have gone up much more than that as professional workers who can ‘work from home’ are seeking to change their lives by moving to regions that allow them to escape the city but maintain a relatively short commute to their main office base should they need to.

He said:

… some analysts have suggested we might lift the cash rate to cool the property market. I want to be clear that this is not on our agenda. While it is true that higher interest rates would, all else equal, see lower housing prices, they would also mean fewer jobs and lower wages growth. This is a poor trade-off in the current circumstances.

That is not to say that there aren’t public policy issues to be addressed here …

More broadly, society-wide concerns about the level of housing prices are not best addressed through increasing interest rates and curbs on lending. While monetary policy is contributing to higher housing prices at the moment, the way to address these concerns is through the structural factors that influence the value of the land upon which our dwellings are built. The factors include: the design of our taxation and social security systems; planning and zoning restrictions; the type of dwellings that are built; and the nature of our transportation networks. These are all obviously areas outside the domain of monetary policy and the central bank.

So quite clearly he is pointing to a failure of fiscal policy and infrastructure policy here.

The tax system (negative gearing) rewards those with high incomes and wealth if they accumulate multiple residences, which then drives up prices because it inflates demand.

The fiscal mindset towards achieving surpluses has starved low income workers of access to affordable ‘social’ housing. Australia has a deficit of around half a million residences at present in this category.

Low-income workers have to compete with those who are better off and have access to more credit and frequently spend too much – which also pushed prices up.

So the inflated demand for housing coming from the tax system distortion pushes up against a deliberately restricted supply (from the surplus obsession).

That is all down to government not the central bank.

Low interest rates would benefit low income workers if the supply of housing was increased as a result of a properly thought out social housing construction initiative.

The construction stimulus would help workers in that industry and the increased availability of affordable housing would provide opportunities for those on low pay to have secure housing and a chance to accumulate some modest wealth before retirement.

Win-win.

So the RBA governor is correct in pushing against the call for higher interest rates.

Those calls often come from those with a vested interest in having higher rates – the banks, those on lucrative fixed income flows, etc.

It is far better to keep rates low and then use fiscal policy to ensure the structural rigidities that are driving housing prices to ridiculous levels are sorted out.

Finally, the RBA governor talked about the QE program.

I will follow up on this topic next week, because I read a very interesting ECB discussion paper this morning which provides further analysis on this question.

But, for now, the RBA governor made it clear that is government bond buying program would continue and has been very beneficial in a number of ways:

… keeping funding costs and lending rates low across the economy; ensuring that the financial system is very liquid; supporting household and business balance sheets; and contributing to an exchange rate that is lower than it would be otherwise. It is through these transmission mechanisms that our policies are supporting, and will continue to support, the recovery of the Australian economy over the months ahead.

They are clearly going to maintain the program until at least February 2022.

The RBA recognises that:

1. There is no inflation threat on the horizon.

2. The RBA has an important role to complement fiscal policy stimulus, which they acknowledge “is the more effective policy instrument in responding to the Delta outbreak. This is because fiscal policy can use the public balance sheet to offset the hit to private incomes during the lockdowns.”

3. Conversely, “In contrast, monetary policy works mainly on the demand side and the effects on income are felt with a lag; realistically, there is little we can do to offset the hit to demand in the September and December quarters. ”

4. They have now “hold around 35 per cent of the Australian Government bonds on issue and 18 per cent of the state and territory bonds” which represents “a substantial and ongoing degree of support to the economic recovery”.

How?

By subverting any chance that the bond markets can push up yields using the pretext that the fiscal deficits are too high.

This way, the RBA keeps yields low and spurious arguments about ‘increasing cost of government spending’ etc, which are wrong in principle anyway, are not able to surface and distort the policy debate.

Everyone can see that the relatively large fiscal stimulus over the last two years (notwithstanding the reduction this year) has been injected at a time when inflation is low and bond yields are very low.

They are learning that the central bank can always control yields on government debt including driving them into negative territory.

They are learning that the narratives about government debt and yields and crowding out etc – all important myths that are used to restrain government spending and maintain unemployment rates at elevated levels are false.

So that is a good outcome from the shift by the RBA towards QE.

They are directly funding deficits – even if they claim otherwise – and the people can see the sky is still over our heads.

Music – Lazy Lester

This is what I have been listening to while working this morning.

Yesterday, I featured the post minimalism of Max Richter. Today we go to Louisiana and bring the not very well-known singer and harmonica player – Lazy Lester – to the fore.

Lazy Lester could sing, play guitar really well and feature on harmonica. In the 1950s, he was one of the founders of what has become known as the – Swamp Blues – which is a Louisiana variant that combines the traditional delta blues and R&B with – Cajun and Zydeco – influences.

Lots of shuffle patterns, with reverb and tremelo on guitars and very clean and sparse drumming.

And who took the form up in the 1960s? The Rolling Stones, Kinks and Yardbirds brought the sound to the White audience in Britain and beyond.

Appearing on guitar on this 2001 album – Blues Stop Knockin’ – is – Jimmy Vaughan

The track today is ‘Sad City Blues’ and the feature players are:

1. Derek O’Brien – resident guitarist at – Antone Records – in Austin, Texas.

2. Sue Foley – guitar.

3. Sarah Brown – house bass player at Antone’s Blues Club.

4. Gene Taylor – piano. He died earlier this year in Austin during a cold snap and he was unable to afford heating in his home.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Mr bill

What your opinion about Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)?

I would appreciate hearing your thought on this matter..

Have you seen the latest offering by the OECD?

“Another legacy of the pandemic will be higher public debt. Future fiscal strategy should be framed in the context of future budgetary pressures and monitored by an independent fiscal institution. Tax reform will be necessary to reduce Australia’s reliance on taxing personal incomes, which leaves public finances vulnerable to an ageing population.”

Allan,

That is exactly how Wren Lewis and Portes would frame it in the UK. Have done for years and typical liberal nonsense who claim they are from the left.

Remember this in the Guardian in December 2019 from Wren Lewis, after they got rid of Corbyn and he had the man he always wanted in charge of Labour a liberal lawyer.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/11/brexit-tax-cuts-spending-conservatives-labour

This was just before the virus and read what Wren Lewis says in his article. Then compare that with the reality aftwerwards..

The liberal left are either incredibly stupid or paid up members of MI5 which wouldn’t surprise me at all. Pen pushing geopolitical narratives whilst destroying their own country and calling it peace.

EU uber alles is the narrative of peace they say no more wars within Europe they cry. If what they did wasn’t a war against Greece and Italy and the Catalans then I don’t know what is. Just a different type of war was imposed on the people of those areas within EU uber alles. That the OECD would fully support each and every time.

Wren Lewis has changed his stance on public debt since December 2019 mainly because of MMT. Offer him independent fiscal councils filled with a bunch of liberals and he would bite your hand off.

@allan. Noted the OECD “ prescription” for dealing with the aftermath of the pandemic. No doubt Australia’s former Finance Minister (Mathias Corman is advising them in his new role as head. Exporting ignorance ?

This is not the first time the Philip Lowe has said something sensible, but it looks like he might be pulled back onto the neoliberal line by the “economic girly man” at the OECD, and The Cormannator’s cheer squad in our neoliberal government are practically gagging for it!

I know Bill has made a very convincing argument against the depoliticisation of Reserve Banks generally, but is it possible that the revolving door of power and money has spun so far that an “independent” Reserve Bank has now become a threat to their rapacious value extraction?

Maybe the owners of capital have done such a good job at capturing our government that they no longer need to persue depoliticisation – why install “independent” experts when you’ve captured the idiots. Either that or they are about to use the OECD to tell those reserve banks that independence only works if they shut up and do what they’re told.

Just read another article in SMH, looks like the corporate media and the whole mainstream economics profession are lining up to blame the Reserve Bank for failure to meet its inflation or full employment targets. Both fiscal policy failures!

I am concerned about the conventional measures of inflation. It seems to me there is no objective way to measure inflation, at least not in the current, conventional manner. The RBA site tells us:

“In Australia, the CPI is calculated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and published once a quarter. To calculate the CPI, the ABS collects prices for thousands of items, which are grouped into 87 categories (or expenditure classes) and 11 groups. Every quarter, the ABS calculates the price changes of each item from the previous quarter and aggregates them to work out the inflation rate for the entire CPI basket.”

Then, after a simplistic box calculation which elides many factors, the RBA tells us:

“In deciding which goods and services to include in the CPI basket and what their weights should be, the ABS uses information about how much – and on what – households in Australia spend their income. If households spend more of their income on one item, that item will have a larger weight in the CPI. For example, the ABS included smart phones in the CPI to reflect consumers taking advantage of advances in technology. Data on household spending across all items is only available approximately every five years or so.”

As we go on in this abbreviated public information document (for sure it’s not a treatise on inflation measurement) we learn that there are a number of limitations in official inflation measurement. It mentions directly or indirectly issues of;

(a) Broad sampling difficulties;

(b) Sampling limitations (time and region influenced);

(c) Basket choice (and by implication lack of tailored baskets for different groups like pensioners);

(d) Quality and quantity changes and use of or lack of use of hedonic adjustments;

(e) Substitution bias.

There is also the fundamental problem that the numéraire (the Aussie dollar in our case) is not an objective measure of any fundamental and objective real dimension. It is an unreliable measuring stick. It’s own value changes, against everything, and chain-weighted inflation measuring techniques are used or not used depending on the philosophy of the measuring agency. The arguments around this issue can be found in Capital as Power (CasP) literature.

If one looks at the history, one sees measuring agencies change inflation measuring methods over time and governments can at times selectively include or exclude items (goods and services) according to whether they want a particular item to influence or not influence an inflation measure, headline, trimmed mean, underlying etc. All of this opens inflation measuring to neoliberal rigging and such governments have incentives to massage figures and to ignore certain kinds of inflation like asset inflation. Also long time series of inflation are compromised by changing meaures and methods.

Given the above, my question is this. How reliable are neoliberal, conventional paradigm, inflation measures for developing heterodox macro critiques and prescriptions for alternatives?

Ikonoclast, I think there is only one thing that you can measure exactly in economics – spending in dollars.

All other concepts, e.g. supply, demand, employment, inflation, value, money supply etc. are subject to the limitations similar to those you pointed out.

We can have estimates of those values, which can range from very accurate to completely bonkers, but as long as we are aware of the biases and limitations of data collection we can have informed discussion. You need look no further than Bill’s breakdowns of employment data for an example.

Thank you for today’s swamp blues – it takes me back to growing-up teenage years in Austin Texas, pre Antone’s, where the only place to hear this music was in Austin’s segregated east side, Charlie’s Playhouse. Anywhere to hear this live here in Australia post-Covid? And a even bigger thanks for educating me (on-going) in macroeconomics/MMT.

Ikonoclast

“Given the above, my question is this. How reliable are neoliberal, conventional paradigm, inflation measures for developing heterodox macro critiques and prescriptions for alternatives?”

Scott Fullwiler: Some Reflections on Prices, Inflation, and Macroeconomic Policy goes into a bit of this on the video below on how the FED does it.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=aqEk2SbsYiU

And John T Harvey looks at it in a different perspective.

You look at world war 2 and analyse every business cycle from then to now. Rather than just look at a graph over the same period.

Have a look at where the price pressures materialised first . Which sectors are affected the most. When things start to heat up and unemployment levels start to get low. Once you identify the common sectors that tend to feel the price increases first you know what commodities tend to be effected the most. Rather than what the right says which is all of them, each and every commodity via their flawed anlysis.The

In every expansion there will be sectors of the economy that tend to be restricted first. Once you know that after studying every business cycle since world war 2 then you will know what to keep an eye on at the end of every economic expansion.

You don’t stop the expansions by slashing demand to bring prices down and leaving 5% and more of the population unemployed. which is the neoliberal response and answers your question. Not only how they measure it is wrong but there reaction to it even more so.

Once you identify the common commodities that tend to inflate first. You would help the market sort them out and invest more resources into those areas. To help them increase output without hurting the climate.

Historically which sectors restricted the most and how did that effect commodities is quite a good way at looking at it. Rather than ALL commodities rise at the start of an expansion and ALL decrease at the end . Which is never the case and complete Hogwash.

Then you have the MMT way of looking at it which you will know and that is planning. Finding out what you have at your disposal before a spending policy which is by far superior way of doing it.

I would find the full version of Scott’s video as he is discussing it with other economists as it is very interesting how they look at it.

@zaff ag

Rohan Grey (MMT writer) has written about digital fiat currency here:

https://rohangrey.net/files/banking.pdf

“They (the RBA) are directly funding deficits – even if they claim otherwise – and the people can see the sky is still over our heads.”

And they ARE claiming otherwise, as Lowe said in a reply to Adam Bandt (reported by Ross Gittins in his SMH article entitled “Funding the budget by printing money is closer than you think” (google it):

P. Lowe: “I will resist any assertion the Reserve is funding the government”.

Lowe is perpetuating a fraud, no other description for it….no doubt so he can stay onside with other fraudsters like Jerome Powell in the US who claims MMT is nonsense.

The real issue behind over-priced housing continues to be avoided.

The RBA governor washes his hands of responsibility. He argues that reform of ‘structural factors’ (taxation, planning and zoning) is the solution.

People have been banging on about the need to eliminate negative-gearing and reform capital-gains arrangements (in Australia) for decades. But action is never taken.

And THAT is the problem.

So, why is action never taken?

Self-interest. Those with vested interest are too numerous and powerful. It’s very simple. But not highlighted.

Instead, we have discussions about ‘structural factors’ which are really just a smokescreen to avoid the real issue.

Until the obstacle of self-interest is cleared, everything else is hot-air.