The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force data today (June 19,…

Using a regional lens reveals the uneven impact of the COVID employment crash

Today, we have a guest blogger in the guise of Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period of time. Today he is writing about the uneven impact of the COVID employment crash. This theme – the spatial unevenness of fluctuations in aggregate economic activity – is one we often explore (in our past research together) because understanding these patterns is essential for designing appropriate policy interventions. It is one of the reasons we both favour employment creation programs that respond to local conditions, like the Job Guarantee. It is also the topic a new large grant application that we are currently putting in (as part of the annual funding circus in Australia). Anyway, while I am tied up today it is over to Scott …

Using a regional lens reveals the uneven impact of the COVID employment crash

It’s research grant writing season for many research focused academics here in Australia and so I have spent some time thinking about how the economic slowdown associated with COVID has impacted on the economic performance of regions across Australia.

As a precursor to distilling my understanding and ideas I have been reading some literature about regional economic change, and in particular a collection of material that emerged internationally following the GFC looking at regional transitions following significant economic shocks.

I have also started looking at the Australian Bureau of Statistics Payroll Jobs data which has been released regularly since the start of the economic slowdown in 2020 and is available at a couple of different aggregate regional levels.

The overall focus of the research proposal we are putting together is to identify the different patterns and trajectories of employment in regions as a result of an economic shock. The COVID-19 induced economic slowdown therefore provides the perfect backdrop for the Australian context.

It is certainly the case that the impact of the COVID-19 economic slowdown has not been regional neutral (i.e. all regions have been impacted the same).

The hypotheses we will want to be testing revolves around the extent to which Australian regions might follow one of several paths:

- regional economic rebound, a period or periods of decline followed by a movement back to a previous (pre-covid) path;

- negative regional economic hysteresis, a period or periods of decline followed by a lower than expected rebound;

- positive regional economic hysteresis, a period or periods of decline followed by a higher than expected rebound.

We will, all things going to plan (that is, our proposal is funded), be modelling employment changes across regional Australia to test these hypotheses in the current context.

In the meantime, we can begin to understand some of the potential by considering the Australian Bureau of Statistics Payroll jobs index aggregated to the Statistical Area 3 level, and adding in some selected independent variables taken from the most recent census.

The methodological details of the index can be found here -Weekly Payroll Jobs Australia Methodology- and for context Statistical Area 3 (SA3) represent:

… the functional areas of regional towns and cities with a population in excess of 20,000 or clusters of related suburbs around urban commercial and transport hubs within the major urban areas.

Bill has already discussed payroll jobs index in a number of past blog entries. See for example:

1. Australian labour market continues to go backwards as government sits idly by (October 20, 2020).

2. Worst is over for Australian workers but a long tail of woe is likely due to policy failure (June 16, 2020).

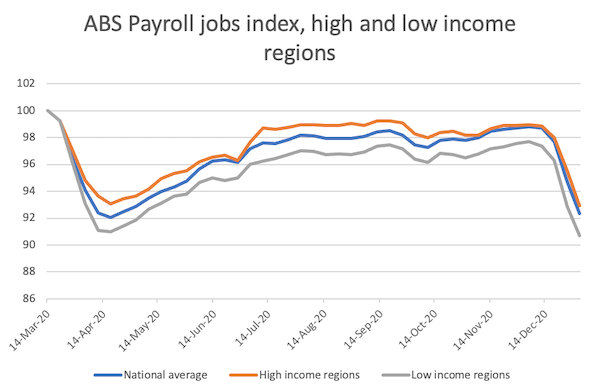

The first graph combines data for the top 10% and bottom 10% of regions according to median household income with the payroll data.

The lines are the average payroll jobs index for the respective groups of regions (high and low median income) with the index for Australia included as a reference.

The series is indexed to the week ending 14th of March 2020, the week in which Australia recorded its 100th confirmed coronavirus case and is up to the first week of 2021.

Each line follows roughly similar trajectories across the period.

The most significant changes are clearly at the beginning of the series, which is the impact of the COVID-19 economic slowdown (or shutdown) when we saw considerable job losses across the board.

The second significant fall is during the period at the end of the series following Christmas and the New Year.

You can find the data for this graph at – Source.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics tells us that:

The movement in the Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages series observed between late November 2020 and early January 2021, is consistent with labour market seasonality at year-end. Estimates may also be affected by modified business reporting of STP data over this period. The underlying movement at year-end in both payroll jobs and wages, will be somewhat hidden by these effects until ‘normal’ business reporting resumes.

And that

The Australian labour market has a period of pronounced seasonality from December through to January due to:

- increases in labour market activity before Christmas; and

- a combination of public holidays, school holidays and lower business activity (in many industries) in the period after Christmas.

Estimates currently presented in the Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia release are an ‘original’ data series and are not yet able to be produced with seasonal impacts removed (i.e. seasonally adjusted).

What is telling about the comparison between low- and high-income regions is the magnitude of the changes in jobs between the two groups.

If the impact on employment of the slowdown was regional neutral, then we wouldn’t expect to see a difference.

But, as we can see low-income regions, on average, saw more jobs disappear in the initial fall and this gap has continued throughout the series.

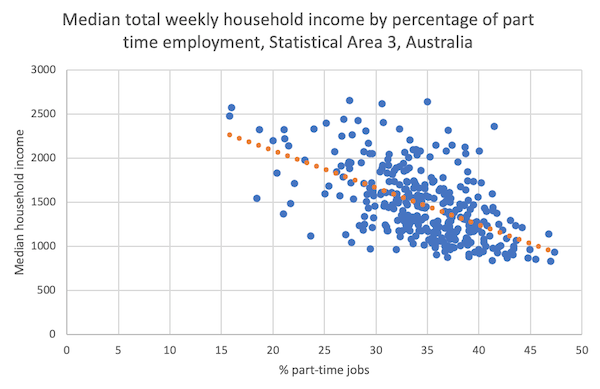

This is likely to be a function of the labour market characteristics of these regions, where the lower income regions are more likely to be characterised by less secure, precarious forms of employment, the very type that were most impacted by the slowdown, a point aptly illustrated by considering the association between regional level part-time employment and household income.

We also note that jobs rebounded in both groups, although by not enough, following the introduction the federal government’s Jobkeeper (wage subsidy) support packages, but with a clear gap continuing between both groups across time.

Eyeballing the data, there are two conclusions I would make.

The first more general one is that the government’s packages have not been adequate to cover all job losses as a result of the imposed shutdown.

If they had been, then the payroll jobs index would be heading back to its initial base for all regions and the government could really be trumpeting the success of its program (this is putting aside what was happening to jobs prior to the slowdown, which raises a whole set of other issues).

The second, and in some ways more concerning conclusion is that the government’s interventions have not been evenly shared across the nation and have generally failed people and communities in the lowest income regions of the country.

We could reasonably expect that if the government’s interventions had been (a) well targeted and (b) larger in magnitude of total support, then all things considered, the gap between the regions would have narrowed.

So higher income regions appear to have been somewhat shielded from the full extent of the jobs wreckage as the government’s interventions appear to have been more favourable to these regions.

Once again, we are all in this together according to the Prime Minister – except when we are not.

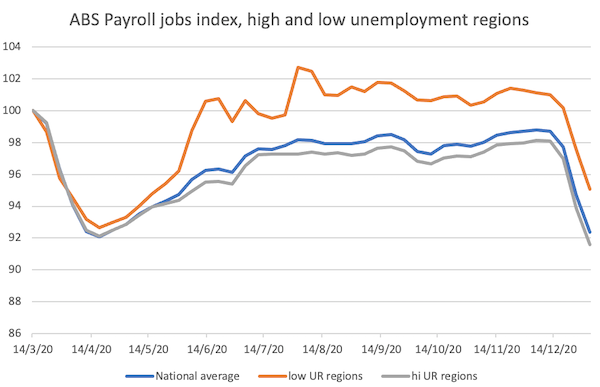

The second graph is similar to the first, except it represents the top and bottom 10% of regions according to the pre-pandemic unemployment rate. Again, the lines represent the average payroll jobs index for the respective groups of regions (higher and lower unemployment) with the index for Australia included as a reference.

Different data, similar outcome.

The data is available at – Source.

Again, we see the impact of the initial economic shock and what is interesting is that the magnitude of the impact is largely consistent across the two groups of regions. This is where the similarity ends.

While the regions with lower pre-pandemic unemployment (and therefore presumably stronger performing labour markets) experienced an initial drop in employment, subsequent periods have seen a bounce back in these regions, on average, to pre-pandemic employment levels.

A scan of the raw data suggests that some of this is driven by what might be considered regional outliers (some of the islands that make up Australian territory) where the payroll jobs index bounced back considerably presumably because these places were much less impacted being completed separate from the mainland).

Removing these outliers (I haven’t included the graph) changes the magnitude of the difference between the two groups, but not the overall pattern.

The story for the higher unemployment regions is commensurate to the low-income regions above.

Regions with higher levels of pre-pandemic unemployment saw an initial fall in jobs as the economy headed to a standstill and have, on average failed to claw back much ground in the interim, and at least to a casual glance, actually fallen further behind.

So once again, we are all in this together, except when we are not! More disadvantaged regions in term of pre-pandemic labour market conditions were hammered and the government’s job keeper interventions do not seem to have only made limited inroads in these regions.

I could consider other data, but the pictures would be very similar.

The take home message is clear and painful.

As always, those who are in most need are the ones that miss out and it seems that the government imposed (not real) limits on help is making that issue worse.

When we use a regional lens to consider economic outcomes we are faced with another picture of social and economic winners and losers, that is sometimes lost when national or state scale data is considered.

Moreover, these patterns have always been there, they are once again highlighted by the COVID induce economic slowdown.

So as I have written about before, the accumulated social wreckage that is a feature of the failed neoliberal experiment is once again brought into sharp relief. A regional lens highlights this even further.

Using a regional lens also highlights the issue of the potential for regional effects to impact on individual outcomes.

Although there is always talk about Australia bouncing back and the nation’s stella performance, the truth is, and many of us know this, where you live makes a huge difference to your opportunities.

Bill and I have researched this in a number of academic papers in the past.

For example, this peer-reviewed article in Geographical Research (July 2009) – People, Space and Place: a Multidimensional Analysis of Unemployment in Metropolitan Labour Markets – identified that regardless of your individual characteristics (level of education, family background etc), the type of regional labour market you live in has a significant impact on your employment opportunities.

That seems like a no brainer, but is often overlooked when policy is being considered and when politicians talk about how robust the Australian labour market is.

And a regional lens introduces even more issues.

We know from research that if you live in a disadvantaged region or community you are likely to have poorer access to services, less positive role models, less opportunities, all of which in many cases add to the already dire position that people find themselves in.

It can be no accident that time and time again, when statistics are released about regional disadvantage that it is usually the same places that pop up again and again.

In my 2005 book – Fault Lines Exposed – for example, we identified those regions that were the most disadvantaged across a large number of social and economic variables, and often these were the same places we identified in our earlier publication – Australia’s regional cities and towns: Modelling community opportunity and vulnerability.

They were also very highly correlated with the many distressed places that Bill and I identified in our – Index of Prosperity and distress

These enduring patterns reflect the general failure of government to address any of these issues is a sustainable way.

The failure is a reflection of the government’s inadequate level of intervention, which Bill has often talked about.

But as we have seen here the government’s actions also often fail as they fail to grasp that interventions are not regionally neutral.

Scholars who refer to themselves as ‘Regional Scientists’ would argue that this is a failure of policy interventions to be sufficiently place-based and being instead too place-neutral.

Reading some of the research literature available on-line, for example this 2012 article in the Journal of Regional Science – The Case for Regional Development Intervention: Place-based versus Place-neutral Approaches – we learn that (page 140):

… geographical context really matters, whereby context here is understood in terms of its social, cultural, and institutional characteristics. As such, a space-neutral approach is regarded as inappropriate; what are apparently space-neutral policies will always have explicit spatial effects, many of which will undermine the aims of the policy itself unless its spatial effects are explicitly taken into consideration.

From this we might take that a general wide spread policy such as Jobkeeper will result in uneven regional outcomes (as we have seen) because it does not reasonably account for the potential contextual differences between places where the intervention is pursued.

Conclusion

The project grant that we are currently writing will address some of these issues.

Hopefully some funding rolls our way and we can get down to some interesting and fun analysis.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi great post, this is a really important and neglected issue, and one that is present in pretty much every country. Would be interested to see what similar analyses of Canada, the UK or the US would turn up.

Are you missing a graph in this post? You make reference to a “second graph” which has the data regarding low vs. high pre-Covid unemployment regions, but the second graph is the one showing part-time employment to median income. Would be interested to see the graph for with unemployment variable, if you have it available, though I assume it would be fairly similar to the first graph.

Keep up the good work!

I hope this gets funded as it will be a good way to bring down the current one size fits all policy approach at the state and federal levels.

-Fault Lines Exposed- hyperlink is not working.

Dear Zev Moses (at 2021/01/11 at 1:10 pm)

Thanks very much for the comment.

I have fixed the missing graph.

best wishes

bill

Dear Alan Dunn (at 2021/02/11 at 1:38 pm)

Thanks very much for the comment. I have fixed the errors now. Scott uses a different editor to me and that introduces errors.

best wishes

bill

Hi

Perhaps the expression of strong regional & local economic experiences will revive. Kawakawa in the North has a working Linotype machine. We passed through Kawakawa today and discovered this in a local museum. Another local museum we visited a few months back described features of the wool industry with photo’s and a description of the institution that ran the buffer stock for wool. The neolib infection has tried to kill of regional, local & community knowledge & managerialise local & regional politics. Good luck!

Jim

If I may professors, I would use a different narrative and research design altogether if I want do, or test the hypotheses being proposed. For example, you showed the first graph which painted a picture of how things evolved between the 2 different groups. I can see the logic where you are getting at, but this is not the main story nor analysis you want to propose to show if the government interventions do or don’t work (it can be in the related analysis section, if any).

The key words is the “effectiveness of the government interventions”!

Yes!!!

Therefore, you want to illustrate the difference between before and after the pandemic interventions between groups (and then others related hypotheses like regional level, national level, or other relevant demographic variables like full-times, part-times and so on, you want to include as further evidences).

It is fine to show that there is a gap after the government interventions, but if I am the government, I could argue that that gap existed before the pandemic, and hence, it can exist after the pandemic interventions, but it doesn’t mean that the government interventions didn’t work.

So, the main study should be about comparing oranges with oranges and apples with apples, or within the same groups, first and foremost. The gap across groups tells us that maybe the magnitude of the effects is due to other factors which may have already existed before the government interventions.

One other thing I want to share is that, when we talk about government interventions, we must clearly define what it means, and how we measure it, because someone in the government might get picky and say that – what do you mean by interventions – cash handouts, job creations, local infrastructure investment and so on, or the whole lump of everything? Then, things can get very tricky!

Anyway, I see a big and exciting project ahead of you with lot of data crunching (mainly comparing within groups using mainly paired sample t-test, as a tool).

Good luck with you research proposal grant writing! It is a great project which can be replicated in many countries across the oceans.

I look forward to read the first ever study on the “effectiveness of the government pandemic handing policies” in due time.

It bothers me immensely that a current focus of MMT is the suggestion of ways to crank back up the ecocidal neoliberal engine stalled by Covid, albeit with a JG to make that engine more efficient and marginally more humane. Short-term, such a goal is understandable, but shouldn’t MMT’s long-term, far more crucial focus be the suggestion of ways to take advantage of the stalling of this death machine to redesign a new economy from the ground up? One which is humanly and environmentally sustainable for longer than a few more decades? I know this is talked about here and there in the MMT community, but surely not enough IMHO, not even close to enough. It makes me wonder whether MMT itself has implicitly and subtly succumbed to thinking within the neoliberal Overton window, in which history, at least economic history, has essentially come to an end, and the best we can do is tinker with it.

@Newton E. Finn

We must never forget that MMT doesn’t have any ideology, be that progressive or reactionary or anywhere in between. It can be used to solely/majorly advantage the owners of big capital, at one extreme, or everyone on the basis of a level playing field or at some mix between the holders of capital and the rest or wherever on the spectrum of ideologies. Such use of an MMT understanding is always at the choice of those that are in control of the fiscal levers.

Those of us that follow Bill’s blog are predominantly at the progressive-environmental-equity and fairness end of the spectrum, as best I can tell. The in charge right wing neoliberals already use an MMT understanding and will want to drive society back to do their bidding for the benefit of their big capitalist mates while spruiking the doom and gloom scare of debt and deficit and of the need for balanced fiscal statements. Their cover is now well and truly blown by the pandemic and it is up to progressives to keep pumping this out to the unknowing masses of voters to show that it doesn’t have to be this way and what is possible in the alternative. The people have been unwittingly indoctrinated and/or lied to by both major political parties (tweedle-dum and tweedle-dee) who’ve drunk the neoliberal Kool-Aid for the last 40 odd years.

Yes, Fred, MMT is but a diagnostic lens (with the possible exception, to some, of the “prescription” of a JG). My question, however, concerns why this lens is not being used much more intensively not only to analyze current macroeconomics and suggest revisions to make it more efficient and Covid-resilient, but as an effective and necessary tool in the designing of a new, non-ecodical way of life. IMHO, the extraordinary power of the MMT lens is largely being focused on issues far too small, and this is one of the key reasons, again IMHO, that MMT has not caught on with more of the progressive/radical left. It’s all about “that vision thing” which Bush Sr. admitted he wasn’t very good at. MMT could be of vital assistance in envisioning so much more than capitalism slightly improved by a JG, could it not? Indeed, could it not be used to lay out a viable economic superstructure for eco-socialism? Thrillingly, at least to me, “Reclaiming the State” began to flesh out such a grander vision, and thus I eagerly await the sequel. Am I alone here?

New ton, You are not alone, not at all! I believe that most readers and commentators here have the same dreams and passions. But as I or we have clearly learned from bill’s blog, the change is within and depends almost entirely on political process.

And when it comes to that, I (and maybe we) are so powerless. We cannot even influence friends, some of whom might be an MP or a senator to share our view or be our voice in the crowd let alone a group of them. So, while some of us think everyday how we can implement our ideas to make this world a better place, some others tinker on with other things that is within their power like research and education.

Research leads to new knowledge, education and better decision making.

But change itself can come only through educating the pubic the new ways of thinking or the new ways of doing things (even the lawmakers they also have to undergone the same process for any change to take place).

This mindset helps me bear with reality a bit better while pursuing the nice dreams that you and many other have shared…

Thanks for the wise counsel, vorapot. Even in my 70s, I remain essentially an impetuous youth. And that’s how I intend/desire to go out. So I hope that Bill and the readers of his blog will continue to put up with my zeal/foolishness. I know that fundamental change takes time, but time is so short. “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few.”

Speaking of vision, I’m currently running with the idea of transition to the green economy funded by the BIS with its unlimited currency-issuing capacity. If AGW climate change is real, then “opportunity costs” (re resource use) of funding the transition are redundant (since the planet’s survival is at stake).

Africa could be running on sunshine/wind within a decade, bypassing the fossil-powered route to industrialization taken by the West. A 100% global waste recycling industry is also necessary, funded in the same manner.

Does the UN need to authorize the BIS to fund the transition?