The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

There is no such thing as a free lunch

I guess if mainstream economists use Milton Friedmanesque smears they think that will be sufficent to discredit Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). There have been a few critiques in the financial media recently along those lines. The authors tell their readers that they get the impression that MMT is just about a free lunch. Throw in Zimbabwe or Weimar are few times during the article and there you have it – rather tawdry attempts at maintaining mainstream thinking when the world has entered a new era of fiscal dominance as policy makers discard their reliance on monetary policy to stabilise economies. This policy shift is diametric to what mainstream macroeconomists have been advocating for decades as they repeatedly warned that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would lead to disaster. However, their predictions have been dramatically wrong and provide no meaningful guidance to available fiscal space nor the consequences of these policy extremes for interest rates and inflation. The world is leaving them behind and it is interesting to see how they are trying to reposition themselves.

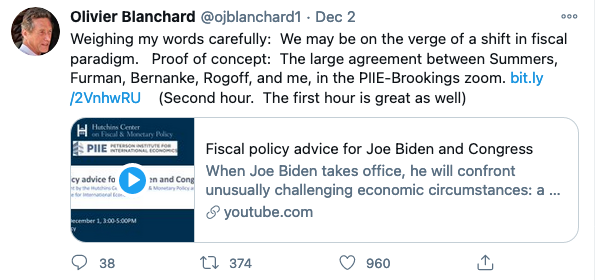

Olivier Blanchard posted this extraordinary Tweet on December 2, 2020:

Breathtaking arrogance!

So, ladies and gentlemen, because Jason, Larry, Ben, Ken and Olivier have decided, it means the fiscal paradigm has shifted.

They determine what goes!

That is, in their desperate attempt to remain relevant when the paradigm they have been pushing for decades, which has devastated economies and peoples’ lives, is now being exposed as a failure, they are jumping ship and putting themselves at the forefront of the new era.

This summarises what is going on at present among many mainstream economists.

There is a lot of it going on.

There is also a lot of economists trying to stay relevant, but realising that MMT economists have been at the forefront of the fiscal dominance for 25 years now, they somehow have to dissociate themselves from MMT by making out it is something different to what it is.

The ‘free lunch’ critique has entered the fray in the last week or so.

It is laughable really that they think people are so stupid that they will accept this sort of stuff.

On November 26, 2020, the chief economist at the AMP (Australia), which is a former insurance company in Australia that branched out into broader financial services including banking, attempted to elucidate his clients about MMT.

His attempt at characterising our work – Modern Monetary Theory – can it help with economic problems or is it just another Magic Money Tree? – is a poor reflection on the author rather than MMT.

As background, the company he works for (AMP) has a rather tawdry record.

For example, this ABC report – AMP scandals threaten to break up the company as profit focus backfires (September 9, 2020) – informs us of “the scandal that may prove to be the straw that broke the camel’s back for a company which once sat at the pinnacle of the Australian corporate ladder.”

It concerns allegations of inside jobs for the boys amidst sexual harassment allegations.

It was the latest scandal in a long list.

During the 2018 Hayne Banking Royal Commission, it became clear that AMP has engaged in misconduct towards its customers – putting profit ahead of ethical trading.

More evidence of the nature of AMP culture is available in this report – AMP Capital sees $2.1 billion outflows as scandal continues to bite (October 22, 2020) and this report – AMP profit crumbles amid royal commission scandals, life insurance sale (February 14, 2020).

Back to the MMT story.

Shane Oliver’s article was a briefing to the ‘markets’.

I would hope that anyone considering investing funds in AMP would realise that the advice coming from the company’s chief economist fails badly.

He makes the introductory error of assuming that MMT is some sort of regime or policy set when he suggests that MMT:

… supporters seem to claim it will solve many of our economic problems.

People who read our work and understand it will know that that characterisation is inaccurate.

MMT is not some sort of regime or a set of policies.

A government does not suddenly ‘apply’, ‘switch to’ or ‘introduce’ MMT.

Rather, MMT is a lens which provides a better understanding of the fiat monetary system and the capacity of the currency-issuer.

By linking institutional reality with behavioural theories, it provides a more coherent framework for assessing the consequences of government policy choices.

MMT allows us to appreciate that most choices that are couched in terms of ‘budgets’ and ‘financial constraints’ are, in fact, just political choices.

Given there are no intrinsic financial constraints on a currency-issuing government, we understand that mass unemployment is a political choice.

Imagine if citizens understood that.

An MMT understanding lifts the ideological veil imposed by mainstream economics that relies on the false analogy between an income-constrained household and the currency-issuing government.

People who have read our work know that.

But then Dr Oliver continues by telling his readers that:

Its easy to get bogged down in the details of MMT, so I will keep it simple.

Ah, avoid the detail – and then start inventing stuff.

He then provides his own key MMT propositions.

Fictional representation 1:

The government can just keep spending until it meets its objectives – whether that’s traditional macroeconomic objectives like boosting inflation or full employment, or conceivably everything else including reducing inequality, dealing with climate change and more affordable housing.

No MMT economist has ever written or said that the government can solve all desirable objectives by spending alone.

The point is that there is no financial constraint preventing government from spending any amount.

But that doesn’t mean there are no constraints.

And dealing with inequality, climate change and affordable housing would surely hit those actual constraints fairly quickly, which means other measures will be required.

I will come back to that.

Fictional representation 2:

Rather than raising taxes or issuing debt, government spending can be financed by the government directing its central bank, eg, the RBA in Australia, to print the money and give it to the government to spend, subsuming monetary policy into fiscal policy.

Taxes and debt-issuance do not ‘finance’ government spending.

All government spending is facilitated by central banks typing numbers into bank accounts.

There is no spending out of taxes or bond sales or ‘printing’ going on.

Elaborate accounting and institutional processes, which make it look as though tax revenue and/or debt sales fund spending, are voluntary arrangements that function to impose political discipline on governments.

Taxes and bond-issuance serve other functions.

Fictional representation 3:

Worries about budget deficits and sovereign debt are overblown if the government borrows in its own currency – so the government can just print more money to finance itself and service its debts and there is no risk of a currency crisis.

The government repays its debt by its central bank altering numbers in various bank accounts – marking down the debt account and marking up the reserves account held by the relevant bank of the recipient of the principal repayment.

No ‘printing’ is involved.

Further, as long as a currency is traded openly on foreign exchange markets, there is always a risk that its value can rise and fall, even sharply and quickly.

However, there has never been a robust statistical relationship established, despite many econometricians trying, between the trajectory of fiscal policy outcomes and the currency fluctuations on the foreign exchange markets.

And, if a currency is facing rather large sell-off pressures which might lead to a ‘currency crisis’, the national government always has the option of imposing capital controls.

Iceland, most recently during the GFC did exactly that and saved their currency from a large depreciation after enduring one of the largest banking collapses in history.

Fictional representation 4:

… contends that a government that issues its own currency can borrow at any interest rate it wants and that all government spending can be financed by debt or money printing – but these are a bit way too whacky for me!

Of course he would want to say that.

His company relies on bleeding people dry through high interest rates and charges.

It is obvious that central bankers can maintain yields and interest rates at very low levels indefinitely to suit their policy purposes.

Bond markets can only determine yields if governments allow them to.

There is no question that that is a true statement.

Further, MMT economists have never stated that “all government spending can be financed by debt or money printing”.

Never!

That is because we do not consider a currency-issuer has any financial constraint, which means it never has to ‘finance’ the spending of the currency is issues as a monopolist into existence.

Further, this ignores the relationship between taxes and spending.

While tax revenue cannot fund spending – given the logical point that we cannot pay taxes in the currency the government issues until it has been previously spent into existence – it doesn’t mean that taxes can be set to zero.

Clearly, all spending carries an inflation risk.

If nominal spending growth outstrips productive capacity, then inflationary pressures emerge. Government spending can always bring idle resources back into use, without generating inflation.

At full employment, a government wishing to increase its resource use has to reduce non-government usage.

By curtailing private purchasing power, taxation, while not required to fund spending, can reduce inflationary pressures.

So in this sense, a larger tax base allows for a larger public share of total spending. This is not about ‘financing’ though.

It is about what constraints governments actually face.

After telling his readers that the old Classical Quantity Theory of Money is relevant (linking money supply to inflation), which is the basis of Friedman’s Monetarism and is why they claim central banks should never buy government bonds (which in his language means directly or otherwise funding government spending), he backtracks and cites:

… the already well-known failings of the quantity theory of money …

So why cite it as if it is knowledge?

Because he had to get in the bit about the “Weimar Republic in 1920s” and hyperinflation and somehow insinuate that MMT economists are discredited by these historical episodes.

Extreme supply shocks explain the hyperinflation of 1920s Germany and modern-day Zimbabwe, both of which are regularly, but erroneously, claimed to demonstrate the danger of fiscal deficits.

The Zimbabwean government’s confiscation of highly productive white-run farms to reward soldiers, who had no experience in farming, caused farm output to collapse, which then damaged manufacturing.

Even if the government had have been running fiscal surpluses, the hyperinflation would have occurred such was the depth of the supply contraction.

Please read this blog post – Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 (July 29, 2009) – to get straight on that issue.

He then agrees that the recent history has shown the basic claim of mainstream economics that if the central bank just credit bank accounts to facilitate government deficit spending inflation will accelerate is plain wrong.

He also agrees that the manic obsessions about fiscal deficits and public debt (the “budget austerity obsession” in his words):

… are overblown for countries that borrow in their own currency.

Okay.

But then we get punchline 1 – MMT:

… gives the impression there is always some sort of free lunch. That the central bank can just print money – like some sort of Magic Money Tree – and all economic problems can be solved. But as an old friend of mine used to repeatedly remind me, “you can’t make something out of nothing.”

Which is the grossest misrepresentation of our work you could find.

In 1975, Milton Friedman published his propaganda book – There’s No Such Thing as Free Lunch – which is a sort of catch cry of the anti-government lobby.

It was just a compilation of his media articles.

Economics students were forced to read it as their indoctrination proceeded.

But to suggest that MMT proposes no constraints on government spending is malicious and ignorant at the same time.

Come on Shane, cite on article from an academic MMT economist where you were able to conclude (get “the impression”) that we think there is a free lunch!

Otherwise, you are guilty of making things up to blacken the reputation of these economists, including me.

At the heart of all the MMT writing is the recognition that at full employment, a government wishing to increase its resource use has to reduce non-government usage.

MMT defines fiscal space in functional terms, in relation to the available real productive resources, rather than focusing on irrelevant questions of government solvency.

An MMT understanding allows us to traverse from obsessing about financial constraints and all the negative narratives about the need to ‘fund’ government spending, to a focus on real resource constraints.

It focuses on how policy advances desired functional outcomes, rather than the size of the deficit.

To maximise efficiency, government should spend up to full employment.

The fiscal outcome will then be largely determined by non-government saving decisions (via automatic stabilisers).

The only meaningful constraint on government spending is the ‘inflationary ceiling’ that is reached when all productive resources are fully employed.

That message is central to MMT.

If it was understood it – and it is many of our writings – then one could NEVER get the impression that “there is always some sort of free lunch”.

To suggest otherwise, is just craven dishonesty or ignorance. Which one Shane?

Which leads to punchline 2:

Budget deficits and high public debt are not a problem now as there is spare capacity, economies are not overheating and interest rates are low but this won’t always be the case.

It might not always be the case.

First, the interest rate position is irrelevant – although even progressives fall into the trap that all is well as long as interest rates are low.

Second, if the non-government sector spending increases, the fiscal deficit reduces automatically.

Third, MMT economists focus strongly on the fiscal position in context with non-government spending and saving decisions.

None of us have ever said the fiscal position is irrelevant and fiscal deficits do not matter.

It is the context that matters.

For Australia, with an external sector deficit draining income from the economy, the only way the private domestic sector can save overall is if the government runs continuous deficits of varying scale depending on the private saving decisions.

For a nation like Norway, with a very strong external position injecting net spending into the economy, the government may have to run surpluses to avoid inflationary pressures, while still ‘funding’ the private domestic overall saving preferences.

We also get the ‘politicians will go crazy’ argument that circulates when there is nothing else to say.

Apparently, if the politicians work out that the central bank can just given them money to spend they will become “addicted” and the result will be “wasteful government spending and eventually high inflation or hyperinflation”.

He cites the 1970s as an example of the “inflation genie” getting “out of the bottle” and being hard to stop.

Remember the only serious inflation in the post Second World War period that was global had nothing much to do with fiscal policy behaviour.

The 1970s inflation was driven by the politically-motivated supply-shock (oil price hikes by the Arab OPEC nations).

The difficulty was that governments wrongly responded with with contractionary demand policies when they should have fast-tracked energy substitution technologies given the problem came from the supply-side.

Further, the idea there is utility in keeping the wider population uninformed and functioning under the false construction that their taxes pay for government spending and all that sort of lying, because it places a discipline on politicians, who because they are untrustworthy, would otherwise go wild in their spending has a long history.

I discussed these issues in my – My podcast with Alan Kohler (March 30, 2020).

We apparently have reached a point in history where we hate dictators and eulogise the benefits of democracy, but don’t want the politicians we elect to have the flexibility to advance our well-being.

Or in simpler language – “because we don’t trust politicians”.

Remember the famous quote from American economist Paul Samuelson in the interview he did for the film – John Maynard Keynes: Life, Ideas, Legacy – where at the 52:50 mark into the film, he said:

I think there is an element of truth in the view that the … the superstition that the budget must be balanced at all times … aah … Once it is debunked … takes away one of the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. There must be discipline in the allocation of resources or you will have … aah … anarchistic chaos and inefficiency. And one of the functions of old fashioned religion was to scare people by … aah … sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that long-run civilised life requires. We have taken away a belief in the intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year … in every short period of time. If Prime Minister Gladstone came back to life he would say ‘oh, oh what you have done’ and James Buchanan argues in those terms. I have to say that I see merit in that view.

This amounts to a world where the elites can manipulate the fiscal capacity of the state to advance their own interests (procurement contracts at will, bailouts when they mess up, etc) but if we want to do something about unemployment or poverty then the rest of us has to be held in this fictional world that appeals to our instincts of fear and uncertainty.

And, of course we then are encouraged to distrust politicians and so it goes.

My view is that once we expose these myths, more sensible political discourse can take place.

And if we do not like our government – that is they go crazy with their spending capacity – then we throw them out of office (in Australia, every three years of so).

They can hardly destroy the nation in three years.

I also think that if the standard of political dialogue was improved, higher quality candidates would seek election and push out the time-serving careerists who dominate all political parties.

It is an extraordinary world where we accept a deception because knowing the truth might require us to act differently (become more politically engaged and demand quality political behaviour).

I don’t accept that proposition.

Conclusion

Another rather tawdry attempt at maintaining mainstream thinking when the world has entered a new era of fiscal dominance as policy makers discard their reliance on monetary policy to stabilise economies.

This policy shift is diametric to what mainstream macroeconomists have been advocating for decades as they repeatedly warned that high deficits and public debt levels and large-scale central bank bond purchases would lead to disaster.

However, their predictions have been dramatically wrong and provide no meaningful guidance to available fiscal space nor the consequences of these policy extremes for interest rates and inflation.

Finally, if you have any AMP investments, then I would immediately follow the recent trends and divest them.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Wonderful blog. Is there any merit in trying to engage Oliver as you have done with Alan Kohler?

“No such thing as a free lunch”

Always wondered who the idiot that said this was and should of known it was Freeman.

Obviously never caught a mud crab in his life.

For about 250,000 years hunter/gatherers, the most basic from of a human economy, no-one paid for lunch. matter of fact hunter/gatherers from coastal and river valley regions spent about three hours a day “working” to provide everything they needed using stone age technology.

Also a matter as of fact a half an hour walk around the Rocks in Sydney was enough to gather a decent green salad for yourself.

Typical neo-classical thinking totally devoid of material reality and based on the belief that if something can’t be turned into money for profit it is irrelevant.

The no free lunch rubbish being used against MMT is about as valid a point of economic argument as magic salt and unicorns.

Great article. I have corrected a number of economists during their presos to investors (insto and otherwise) in recent years when making false claims about what MMT is or isn’t. Very funny at times. When it’s clear they are utterly wrong, they play the man instead of the ball. Apparently I’m a Keynesian and a socialist. Hahaha.

Who’s having the “free lunch” Shane?

This class action follows a recent landmark Federal Court judgment where AMP was ordered to pay a $5,175,000 penalty for “insurance churn” engaged in by AMP’s financial planners which the Court described as “morally reprehensible” and a breach of AMP’s obligations to its clients.

“Because he had to get in the bit about the “Weimar Republic in 1920s” and hyperinflation and somehow insinuate that MMT economists are discredited by these historical episodes.”

When of course we can use the MMT viewpoint to explain the episode in far clearer terms as Phil and Warren’s paper “Weimar Republic Hyperinflation through a Modern Monetary Theory Lens” demonstrates.

Published at GIMMS here: https://gimms.org.uk/2020/11/14/weimar-republic-hyperinflation-through-a-modern-monetary-theory-lens/

Please send it to anybody who plays the Weimar card.

When someone floats in a raft of lies, like the ortodox economists do, they won’t stop at the edge of civilization.

They will step into the vast territory of insult, fear, provocation and beyond.

A marvelously clear and comprehensive statement of fundamental MMT truths. Here are just a few of Bill’s incisive points strung together: “MMT is a lens which provides a better understanding of the fiat monetary system and the capacity of the currency-issuer…. MMT allows us to appreciate that most choices that are couched in terms of ‘budgets’ and ‘financial constraints’ are, in fact, just political choices…. Given there are no intrinsic financial constraints on a currency-issuing government, we understand that mass unemployment is a political choice…. Imagine if citizens understood that…. An MMT understanding lifts the ideological veil imposed by mainstream economics that relies on the false analogy between an income-constrained household and the currency-issuing government…. We apparently have reached a point in history where we hate dictators and eulogise the benefits of democracy, but don’t want the politicians we elect to have the flexibility to advance our well-being.” In this last point on the string, Bill goes to the heart of THE political issue of our time, the fostering of distrust in democratic government–the instrument originally created by the people to serve and protect them–by (1) the plutocratic purchase and capture of such governments to make them serve predominantly plutocratic interests, and (2) the subsequent plutocratic messaging to the people–via the mainstream media, academia, popular culture, etc.–that because of what the plutocrats have themselves done, democratic governments can no longer be trusted. Thus the ONLY vehicle that the people could use to curtail plutocratic interests and instead serve their own (including those of the planet) has been anathematized so as to render the people impotent. Has there ever been a mass deception so blatantly obvious yet diabolically clever? While it’s true that MMT contains within itself no value system to guide the policies of democratic government (with the possible exception of the JG), it does contain within itself the unmasking of this Great Deception, a revolutionary act of political liberation. Thus the plutocrats are right to fear MMT and do all in their power to anathematize it as they have democratic government itself. Otherwise, the jig is up.

Actually I like the “free lunch” metaphor when properly framed:

Scenario 1) millions and sometimes tens of millions of people idle, living in poverty or near poverty, desperate for work;

Scenario 2) Everyone’s working – everyone who wants a job/needs a job – producing goods and services. That’s about as close to a free lunch as you can get. Especially since the goods and services produced offsets the money issued and so –> no added inflation.

Glenn Crowther.

It is good to read your comment today. This admirably amplifies the view that the world should allow all people to give their commitment to looking after others, rather than working for others, ie capitalists, to make the capitalist ‘rich’. Each person should remember this, and all forms of capitalism should die the death.

“The 1970s inflation was driven by the politically-motivated supply-shock (oil price hikes by the Arab OPEC nations).

The difficulty was that governments wrongly responded with with contractionary demand policies when they should have fast-tracked energy substitution technologies given the problem came from the supply-side.”

I really enjoy reading this blog. I’d would be very grateful if you elaborated on the above point in the future. In particular, how fast-tracking energy substitution policies might have impacted the unemployment rates in the UK.

Thanks.

Hello Prof. Mitchell, I been reading you for a long time and I bought one of your books, this is the first time I comment on your blog.

Great article as usual but I wonder if you can clarify something for me, I wanted to ask this for quite some time.

You said:

———————————————————————————————-

“For Australia, with an external sector deficit draining income from the economy, the only way the private domestic sector can save overall is if the government runs continuous deficits of varying scale depending on the private saving decisions.

For a nation like Norway, with a very strong external position injecting net spending into the economy, the government may have to run surpluses to avoid inflationary pressures, while still ‘funding’ the private domestic overall saving preferences.”

——————————————————————————————–

I remember part of a debate between Warren Mosler and Steve Keen when the conversation was revolving around the example of an English customer buying a Mercedes car.

Keen argued that exporting countries de facto “outsource” their monetary policy, in the above example he claimed that eventually (leaving out the presence of a UK branch of Mercedes Benz for sake of simplicity) Daimler would take the proceeds (in British pounds) from the sale of that Mercedes automobile to the Bundesbank (or better say, the ECB) and get Euros in exchange.

Mosler immediately corrected him, he said that only a handful or even less of countries do that (as we know, China for example), in the rest of the world the transaction is completely between private parties, if Daimler wanted to convert the proceeds in Euros it has to find someone willing to giving them Euros in exchange for British Pounds.

So going back to your Australia vs, Norway example, following Mosler correct explanation, if a country is a net exporter and in a position of government budget surplus for years (Norway in this case), eventually the foreign importers of Norwegian products (these importers are the foreign sector providing the Norwegian private domestic sectors of savings) will “run out” of Norwegian Krones (bank reserves or bank settlement balances, whatever we want to call them, denominated in Krones) to pay for them.

So what happen in this case?? While it is true that other than China and few other countries, no central bank continuously exchange foreign currency for local currency reserves “on demand” but eventually they have to intervene to prevent an excessive appreciation of their currency which would hurt exporters….so back to Norway, their central bank (part of the government) at some point it has to buy foreign currency and provide enough Krone reserves/settlement balances to buy Norwegian products in light of continuous government budget surpluses.

The situation is the same for Norwegian companies billing directly in foreign currency, eventually they may want to convert some of their foreign currency holdings so they have to find enough Krones without impacting the exchange rate too much.

Am I correct??

Thank You!!

“So what happens in this case??”

What happens is banks. It goes roughly like this.

It’s important to remember that an FX transaction between floating rate currencies is actually two contracts. One is Bank A putting Bank B in credit with Currency A, and the other is Bank B putting Bank A in credit with Currency B. These contracts are assets of the banks, which can then be discounted into the currency the bank operates in. That creates the matching liabilities, which are deposits and which can then be used to pay people in the other currency area.

E.G. A Norwegian Bank contacts a US bank and agrees a contract to purchase 1000USD for, say, 8733NOK. That price is just agreed like any other price for a contract. The ‘exchange rate’ is just the banks shopping around between each other.

The Norwegian bank now has a contract from the US Bank to credit it 1000USD. The US Bank similarly has a contract from the Norwegian Bank to credit it 8733NOK.

The Norwegian Bank takes the 1000USD contract asset and discounts it to 8733NOK on its books (marks up the liability out of nothing) and then credits the account of the US Bank at the Norwegian bank with that 8733NOK – fulfilling its side of the contract.

The US Bank takes the 8733NOK contract asset and discounts it to 1000USD on its books (marks up the liability out of nothing) and then credits the account of the Norwegian bank at the US Bank with that 1000USD – fulfilling its side of the contract.

The contract assets are now replaced with deposit assets in the other bank. The Norwegian bank has an account with the US Bank with 1000USD in it and the US Bank has an account with the Norwegian Bank with 8733NOK in it. The balance sheets all balance.

A US importer hands over their $1000 and asks their bank to pay a Norwegian producer for a consignment of salmon. The US Bank deletes the (additional) $1000 deposit the US importer holds and then contacts the Norewegian bank and asks them to transfer the 8733NOK to the credit of the salmon producer.

The result is a Norwegian Bank with a $1000 deposit, who gets a statement from the US bank showing which account their dollars are in…

The Norwegian state then taxes in NOK and adds that tax to the Norwegian State Sovereign Wealth fund (where money goes in, but can never come out). The Sovereign Wealth fund then buys the $1000 deposit from the Norwegian Bank and uses it to buy USD financial assets.

Hi Neil,

Very interesting and detailed description.

I was a bit confused by the last paragraph though.

I always thought that the Norwegian SWF was a direct depository for Norway’s oil export earnings, denominated – as is all oil trading – in USD.

So why would the Norwegian govt need, or want, to pay NOK tax receipts into the SWF?

The SWF is there to offshore Norway’s enormous oil export-related foreign currency earnings that, if exchanged for NOK and spent domestically, would cause inflation in Norway’s small economy. Nowhere outside of Norway accepts NOK as currency, so there wouldn’t be any use for it in the SWF (which is invested overseas – and, as you imply, only ever repatriated in very tiny amounts: +/- 1% pa).

On payment of Norwegian taxes, wouldn’t the Norwegian central bank just delete the appropriate reserves as the NOK-denominated tax payments were paid into the Norwegian Treasury – as occurs in the UK/US etc?

So, if, as currency monopolist, the Norwegian Govt doesn’t need NOK tax receipts in order to spend, and its SWF is employed to offshore its USD earnings, what logical reason is there for it to pay NOK tax receipts into its SWF?

“So why would the Norwegian govt need, or want, to pay NOK tax receipts into the SWF?”

I think it’s because the value of those oil receipts belongs to the Norwegian outfit that sold the oil. The government owns the Sovereign Wealth Fund, so it has to obtain (by taxing oil revenue) a share of that value to put into the fund. It’s a domestic transaction between the government and citizens who have earned wealth offshore.

“So why would the Norwegian govt need, or want, to pay NOK tax receipts into the SWF?”

Because that’s how they swap out the foreign currency in Norway from those firms earning it for the local currency. It is used to buy foreign currency which stops the currency pair going sky high.

From note 1 to the Statement of Changes in Owner’s Capital in the latest report of the Norwegian “Government Pension Fund Global”.

“There was an inflow to the krone account of NOK 32.3 billion in 2019, while NOK 18.9 billion was withdrawn from the krone account. Of this, NOK 4.5 billion was used to pay the accrued management fee for 2018, and NOK 14.4 billion was transferred to the investment portfolio”

Thanks for the description, Neil. I knew it must have something to do with the SWF but had no idea of the mechanism.

“On payment of Norwegian taxes, wouldn’t the Norwegian central bank just delete the appropriate reserves as the NOK-denominated tax payments were paid into the Norwegian Treasury – as occurs in the UK/US etc?”

Reserves don’t get deleted. They credit the central funds which may or may not reduce balance sheet sizes depending upon the debit/credit position of those accounts at the time. In UK terms the Consolidated Fund account at the Bank of England is credited by the amount of tax collected. However National Insurance Contributions are transferred to the Debt Management Account Deposit Facility instead on behalf of the National Insurance Fund. The Norwegian fund will use a similar accounting diversion approach.

Neil

Thank you very much for the detailed explanation.

So, basically the foreign transaction happen between bank entities so there will be always enough Krones (on the Norwegian side) to execute that transaction, as you said, in the FOREX contract, banks will create liabilities in their domestic currency out of nothing at will (unless they bump into capital ratio issues) and the Norwegian Central bank, as per standard operations, will always supply the necessary reserves if at some point down the road there is stress in the interbank market…am I correct??

Forgive me for the stupid question but…..if there is always enough currency (bank liabilities created at will out of nothing) to cover a FOREX transaction, where the pressure on the exchange rate arise??

Thank You!!

“where the pressure on the exchange rate arise??”

In a simple term and in general, it has to do with the current account balance position of a country, at the time. All other things are just accounting procedures (including the creation of liabilities at will) and the diversion strategies (short and long term, like SWF) of a nation to maintain her exchange rate in compliancy to her government’s economic especially the foreign trade policy/or structure. I think.

(I got all these from reading all the relevant comments above, especially from Neil and also reading Bill’s blog posts on the sectoral balances, and his excellent macroeconomic textbooks).

Am I correct…

“Am I correct…” Add in the willingness to save in that currency by external holders of it.

“unless they bump into capital ratio issues”

Capital ratio issues are solved after the fact. It’s just a matter of price. To purchase bank capital you use bank deposits which they have already created. It’s the job of the bank’s treasury department to make the numbers look good.

That’s why the ratios have little direct control function. All they do is change the price of money.

“will always supply the necessary reserves”

Reserves are systemically irrelevant in interbank operations outside of regulation. Central banks are a collateral optimisation mechanism as far as the payment system is concerned – nothing more. They are used because they are cheaper and more convenient than the “over the counter” alternative.

The obsession with reserves is largely a USA phenomenon. In the parts of the world where we know how to do banking properly, we look at that with amusement.

“where the pressure on the exchange rate arise??”

The pressure arises when a bank or entity doesn’t want to hold a deposit in the currency. You have to find a counterparty willing to do the exchange – which they will only do if they can use that exchange to make money elsewhere. For some pairs that is more difficult than others – and supply and demand then determines the price. Any bank in Norway knows that if they end up with a USD deposit they can usually offload it to the Norwegian Pension Fund for NOK. Therefore they will be willing to do the exchange. And that makes it easy for exporters to sell their oil and fish for USD, knowing they can get the NOK necessary to pay their staff in Norway. I suspect the price setter is the Pension Fund’s demand for USD.

Thanks Neil, very informative.

Excellent post as usual.

The levels of inequality we have today are just barely tolerated by the masses, probably because of what remains of a once solid belief in the ur-liberal concept of market-based meritocracy (at least in those parts of the industrialized world that saw some upwards mobility within the last generation). The market, as unbiased arbiter of merit, provided the moral justification for what has become blatently unjust. This is why some have stated that meritocracy (and the will of the market) is to capitalism what aristocracy (and God’s will) was to feudalism. It remains to be seen if this shift, remarkable as it is and more or less predicted by anyone with a grasp of MMT, will be enough to tilt the scales of public opinion significantly.

In any case, and even if It is no small thing they are ready to forfeit supply-side absolutism, I’m still not fully willing to believe that high-priests of neoliberalism cannot reinvent themselves and their gospel to accomodate a new era of fiscal policy supremacy just like the catholic church came to terms with the heliocentric world view or the big bang theory.

The influence of said church has waned considerably through the centuries, though, so here’s to a chance at something better for the many!

Neil

Thank you very much for your reply, however your detailed and articulated explanation generate more need to understand as it does question some of my understanding of MMT.

You said:

“Capital ratio issues are resolved are the fact” and “Reserves are systemically irrelevant in interbank operations outside of regulation”.

Reserves or Settlement Balances are the only way to clear a payment between banks, so why are they “irrelevant”??

After all, this is what Central Banks mainly do, they swap bonds and other financial assets for reserves and vice versa and government spending enter the private sector via reserves/settlement balances on private banks books anyway.

I understand that reserve ratio is irrelevant (the CB will always provide them when needed) but I never thought of reserve/settlement balances themselves being irrelevant. Coupled with your statement that capital can always be bought with the same deposit created out of nothing (I’m talking about a single bank not the banking system as a whole) what prevents a bank balance sheet from ballooning to the moon with all sort of dodgy behavior?? I always thought, eventual availability of reserves/settlement balances from the banking supervisor/authority (the CB) to clear payments mainly does it, something the private banks themselves cannot create.

Thank You!!

My insight on the “Free Lunch” thing is

that there is a big free lunch now because of the pandemic.

This would also have been true over 1 year ago, because of the gap between the total savings (US private and foreign) plus the total Gov. spending, which is what the Gov. can spend without inflation and what was being spent.

If the US Gov. spent as much as MMT allows for 2 years, then there would be little free lunch. At that time the JGP would have the nation at less than 1% Un-Empl. It would be just the *additional* total savings (US private and foreign).

ISTM, that this is an important point. That the big free lunch is very temporary.

.

“Reserves or Settlement Balances are the only way to clear a payment between banks”

Banks move payments between themselves by lending to each other. In the horizontal circuit the task of the central bank is to take itself out of the middle of the transactions every day as the inter bank market sets up overnight loans. That’s why it is called “clearing’.

That banks settle those interbank loans in central bank reserves is for cost and convenience reasons. The standard operation of a bank is that of correspondent banking – how international settlements happen. One banks rings another up and organises a transfer.

There’s an argument that central banks have leverage because of the convenience, and that is true. But the leverage has limits. If the banks find a particular central bank too onerous, they will just switch back to using correspondent banking and transferring directly between themselves, possibly outside the jurisdiction. Hence the rise of Eurodollar setups during capital control eras.

” what prevents a bank balance sheet from ballooning to the moon ”

What MMT says. Banks stop lending when they run out of creditworthy customers prepared to pay the current price of money. Banks are asset side restricted, not liability side.

Generally, it is because of a mistaken view of what business banks are in. Banks buy charges over collateral and offer their own liabilities in exchange. There are then terms on which you can buy that charge back. Sometimes a fixed schedule (a repayment loan) or a flexible schedule (an interest only loan). The charges can be fixed charges over certain items (a mortgage for example. The mortgage is the charge, not the loan), or floating charges (what is called an unsecured loan, although when the bailiffs turn up you’ll find that it is very much secured on everything you own). Sometimes they won’t ask for their liablities back – such as when they take complete control of a charge as they do in an FX transaction. And sometimes they will roll the interest and repayment into one agreement (such as with FX swaps, and repurchase agreement loans).

A lending bank is one that takes charges with a view to selling those charges back to the person tendering the charge. An investment bank buys charges with a view to selling those charges at a profit to somebody else, usually with a view to staying in the middle for as little time as possible, preferably not at all (acting as agent).

Banks are little more than pawnbrokers in shiny suits. A creditworthy customer is one capable of offering for sale a charge the bank wishes to purchase.

Neil …. can you elaborate on this?

“If the banks find a particular central bank too onerous, they will just switch back to using correspondent banking and transferring directly between themselves, possibly outside the jurisdiction. ”

So say Wells Fargo and Bank of America want to settle up accounts, but don’t want to do it via their reserve accounts at the Fed …. what would the alternative path look like exactly?

Thank you Neil

I’m still not convinced that reserves/settlement balances are not important and just a convenience. MMT clearly describe the hierarchy of money the horizontal circuit (banks extending credit) and the vertical one (state money, state meaning the consolidated treasury/CB).

Warren Mosler had a famous online debate with Chicago School Prof. Michele Boldrin where the latter was trying to dismiss MMT.

Boldrin screamed “It is not true that I need government money to pay my taxes, I can take a bank loan!!”. Mosler calmly replied, “how is your payment going to clear??” “The treasury wants reserves moved to its account, not bank loans”. That was the end of the discussion.

I’m not disputing the fact that all a bank need is a creditworthy customer to extend credit, they do not worry about having enough reserves beforehand (well, actually very small banks do but this is another discussion), they can always get them afterward…but at some point, somewhere, that issued credit will need to be backed by reserves (state money). After all, pawnbrokers deal in their local state currency they do not issue their own.

Anybody can issue money, the problem is having it accepted. Aren’t bank special because they receive a special license form the state to issue credit convertible in state money, meaning they can convert horizontal money in vertical money?? This is why Central Banks are around right??

When the music stopped in 2008, access to Central Banks facilities was vital.

Eurodollars was a nice way to going around banking regulation but that market was born because all the dollars that flooded Europe after WWII, Reserves backing Eurodollars are still in the books of the Fed, they never leave the United States as far as I know.

“So say Wells Fargo and Bank of America want to settle up accounts, but don’t want to do it via their reserve accounts at the Fed …. what would the alternative path look like exactly?”

Initial position on both banks: A: Loans 200, L: Deposits 200

WF customer pays 100 to BoA customer.

Final position on both banks

WF A: Loans 200, L: Deposits 100, To BoA: 100

BoA A: Loans 200, From WF 100, L: Deposits 300

For a payment to be made, the default is that the target bank has to take the place of the original depositor in the source bank.

“but at some point, somewhere, that issued credit will need to be backed by reserves (state money).”

It doesn’t. The horizontal circuit is entirely stable in its own right. There’s no need for state money at all. But if you don’t have it you will get an awful lot of unemployment and instability.

The net outcome in the horizontal circuit is zero. My deposit is your loan. Net financial assets come from the actions of the vertical circuit.

“The treasury wants reserves moved to its account, not bank loans”. That was the end of the discussion.”

Correct, but what you’re describing is the vertical circuit, not the horizontal circuit. The Treasury account is at the Fed. To transfer to the Fed, you need deposits at the Fed – and an individual can’t really hold those. Instead a bank tenders Treasury securities to the Fed as a charge and the Fed will repo them into Fed liabilities that the bank can then transfer to the Treasury account at the Fed in return for your deposit with the bank being deleted.

The Treasury will then ask the Fed to pay the surplus balance to a bank under the TTL scheme. Which gives the bank their deposit at the Fed back in exchange for creating a liability to the Treasury (which from the Treasury’s point of view is a deposit with the bank). The bank then uses their Fed deposit to clear the repo and get their Treasury securities back.

No additional net reserves required to pay taxes but a few may have been inconvenienced in the process.

You do need Treasury securities as collateral though, and the bank has them because government has spent more into the banking system than it has withdrawn over time, and those excess Fed deposits have been used to buy Treasury securities.

The two circuits may have a one-to-one exchange and the banks make it look seamless, but they are two distinct types of money with their own flow paths.

“So say Wells Fargo and Bank of America want to settle up accounts, but don’t want to do it via their reserve accounts at the Fed …. what would the alternative path look like exactly?”

They would have to trust each other. As a creditor, Bank Tweedledum would have to accept some asset from Bank Tweedledee and believe that it was worth what Bank Tweedledee said.

Reserve balances administered by trustworthy central bank don’t pose many questions that way.

Thanks Neil. Can you elaborate on what this means?

“Central banks are a collateral optimisation mechanism as far as the payment system is concerned – nothing more. They are used because they are cheaper and more convenient than the “over the counter” alternative.”

Neil

If what you describe is the the regular modus operandi, why would we need a Central Bank at all?? Just for “convenience”??

The CB would not be able to control short term interest rates if banks did not need reserves to clear interbank transfers. Rates too high?? Let’s skip them and make up our own numbers!!!

What you describe it’s me getting stuff on credit from a corner store that knows me, it works until it doesn’t.

I remember eating humble pie few years ago when I started to talk about banking with a retired bank executive from a small regional bank in WA state at a family thanksgiving dinner, when I proclaimed “banks do not need reserve to lend”….he was seriously amused by my statement, to say the least.

From his perspective working at a small bank, he told me “Actually no, we did look at reserves, we were careful when extending credits that we had enough reserves and relying too much on borrowing reserves overnight (I repeat, “borrowing reserves”) from other banks”…this is from someone in the trenches….a small bank (but still member of the Federal Reserve System), not everyone is Wells Fargo or Bank of America.

As Mel said, two banks may not trust each other, reserve balances and a CB standing ready to provide them are the mechanism that build trust in banks.

Even by your own words, at some point in the horizontal circuit I may need to turn horizontal money into vertical money and for that I need reserves (“dynamically” provided by the CB).

Every measure of money supply in advanced countries, including these with banking systems working on a 0% reserve ratio, put reserves/settlement balances at the top of the hierarchy.

Neil, also, how is the “To BoA”/”From WF” part accomplished on your example balance sheet?

I thought that that would be via the transfer of reserves.

If not so, the only other ways I could think of is if WF creates a deposit of 100 in an account at WF owned by BoA?

Or both parties maintain deposit accounts at a 3rd “correspondent bank” that’s *not* the CB? Like CitiBank?

Or they have accounts at a clearing house?

Kwn

I think what Neil means is simply that a bank can simply “swap” their liabilities between each other.

In the example, WF created a deposit for BoA for $100 and now BoA, on its Asset side, has a deposit at WF for $100 which matches its increase in liabilities (the receiving customer account).

I’m still not convinced, reserves are still needed to clear. Maybe that is the procedural way you set up a transfer but eventually reserves or settlement balances are needed even if provided “on demand” by the CB.

Banks are obviously free to lend or setting up contracts between each other but the trust, I believe, come from the behind the scene support of their central banks, meaning reserves do matter. The fact that the banks create money (credit money or horizontal money) endogenously disproving the antiquated money multiplier model does not mean that reserves are mere convenience in my opinion.

Domenico, you are right that reserves are not mere conveniences. They are necessary to make the payment system run smothly on a daily basis, or nightly basis should I say.

“but the trust, I believe, come from the behind the scene support of their central banks,”

It’s not a matter of belief. It’s a matter of how banks actually work in reality.

The trust comes from the collateral posted to get the loan – which will be government securities. Prior to the GFC banks lent to each other overnight unsecured. After that they demanded collateral, and the advent of QE reduced the need for banks to lend to each other. In fact that was sort of the point to maintain liquidity ratios.

Similarly you have to post collateral at the central bank to use the intraday loans they offer. And that’s the advantage – collateral optimisation – since the same collateral can then be used to cover intra-day transfers to all the banks using the same central bank group.

But it is not required to do banking. It’s a good way of reducing risk, cost and hassle, which bankers love.

There’s a useful Janet and John description here about how banks work, and you’ll even learn what a Nostro and a Vostro is: https://transferwise.com/gb/blog/how-do-banks-move-your-money

You’ll see that the UK has some of the most advanced bank payment transmission mechanisms in the world. We’ve been doing it a while after all.

NW: “The horizontal circuit is entirely stable in its own right. There’s no need for state money at all. But if you don’t have it you will get an awful lot of unemployment and instability.”

Of course Neil is right, but plainly “stable” / “instability” are being used in different senses here, This exemplifies the slight confusion/disagreement here.

In general, I think it is better to express oneself this way: It’s not that reserves are necessary, to use them for some positive purpose. It is that it is necessary to NOT “not have reserves”. To have a non-negative reserve position. If you keep up a negative reserve position – then the state can close your bank down, etc – and then the two circuits through your bank do NOT have a 1-1 exchange. Especially if you also neglected to bribe enough regulators and politicians (and they probably prefer to be paid in reserves or equivalents.) Neil’s point is that banks can settle between themselves pretty much however they want to do so. Here reserves might be called a convenience. But they are more than that in dealings with the state, e.g. tax payments.

Albeit the state might interfere with correspondence banking functions – for instance if they were being settled in an outré manner – say that of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train. For instance the US government considered forbidding Eurodollar transactions way back when – and had the clout to make them a lot harder, but chose not to exercise it.

I think most everyone knows this, but it is always worth trying to say things more clearly.

The main reason to take the focus off reserves, which is really a peculiarly US obsession, is so that you can analyse currency to currency operations more effectively – since that is where the action is in the rest of the world outside the USA.

Once you do that you find that the internal operations of a country’s banking system works like a currency peg between countries. Which explains how the Eurozone was put together so easily. They just pegged the central banks together, like the commercial banks were pegged together one layer down.

Reserves are just not interesting to the way banks fundamentally work. They’re not even interesting from a tax payment point of view, since taxes end up being paid (via a circuituous route) in government securities (the current system tries to hold reserve quantities constant – because of the belief they have magical powers – and it swaps in and out government securities via repos to maintain the quantity). MMT explains that all this swapping back and forth into reserves is pointless and that government securities and reserves should operate in a pegged fashion, not a floating fashion so they become one and the same. QE is slowly demonstrating they are one and the same anyway.

The central thrust is that the belief that interest rate curves can control the amount of private investment isn’t really delivering the optimal outcome – or even the right sort of private investment. And that perhaps we should stop doing that and adopt MMT Functionalism instead.

“the internal operations of a country’s banking system works like a currency peg between countries”

explain?

“since taxes end up being paid (via a circuituous route) in government securities (the current system tries to hold reserve quantities constant – because of the belief they have magical powers – and it swaps in and out government securities via repos to maintain the quantity)”

Read this a few times but still not getting it … how do taxes end up being paid in government securities?

“explain?”

In the example above was there any negotiation about how many Wells Fargo liabilities were to be exchanged Bank of America ones?

Now rather than Bank of America, do the same with Danske Bank in Northern Ireland in GBP. The first thing to agree is how many Wells Fargo USD to swap for Danske Bank’s Northern Irish GBP.

And that’s because both USD subsidiaries have an agreement with the Fed and they would use that path for USD primarily. Which stops the liabilities in each bank drifting apart from each other.

At the Eurozone level the same applies between the Hellenic central bank and the Bundesbank (for example) via the ECB. And which also shows how you break away from the Euro. You stop promising to exchange at par.

“Read this a few times but still not getting it … how do taxes end up being paid in government securities?”

Government securities + reserves are the net financial assets of the non-govenment sector. Taxes reduce the net financial assets of the non-government sector. If the central bank is trying to maintain reserves constant over time then government securities have to reduce (in net terms) to make things balance.

The effect is generally lost in the aggregate because government is constantly adding new net financial assets to the system via spending at the same time, so it shows up as a net issue reduction – fewer new Treasuries are issued during times of high tax receipts than at times of lower tax receipts.

Neil

Well, replace reserves (or settlement balances if you do not like the US word for them) with government securities and you end up in the same spot. You need them as some point in interbank operations, payment of taxes, etc…this is why we have a Central Bank after all.

Your own videos on the New Wayland channel on Youtube underscore their importance of reserves.

You said:

“The central thrust is that the belief that interest rate curves can control the amount of private investment isn’t really delivering the optimal outcome – or even the right sort of private investment.”

The fact that interest rates (the CB controls directly the short term) is a lousy mechanism for controlling economic activities does not mean that the CB are incapable of setting the rate. After all one of the central tenets of MMT (and Prof. Mitchell remind us of this periodically on this blog) is that bond operations are a reserve management operations to control the short term interest rate, not a government financing one…and MMT does not just describe the US reality only.

“And that’s because both USD subsidiaries have an agreement with the Fed and they would use that path for USD primarily.”

Which path are you referring to here?

“You need them as some point in interbank operations”

That would make letters of credit (which is an interbank operation) impossible in the international trading system, and they definitely happen. What you need is assets and reputation to establish the bank as a creditworthy counterparty – preferably backed by posted collateral, of which government securities is better than a bunch of mortgages.

Reserves are uninteresting in banking terms. Here in the UK, it was an alien notion until 2005. Until then banks just maintained clearing accounts at the Bank of England which had to maintain a minimum balance of zero by the end of the day. Pretty much nothing was held ‘in reserve’ in Bank money. It was all done ‘in the market’ via direct interbank lending (unsecured mostly), with occasional use of the Bank – in the same way as the discount houses had previously operated for centuries.

Reserve systems (‘standing facilities’) were introduced in an attempt to create ‘greater stability in sterling overnight interest rates’.

Similarly the provision of central bank services is about maintaining the interest rate:

Central bank systems are about trying to control the interest rates in a currency by offering the banks various way of reducing their risk and costs so they will agree to transact in that currency across the books of the central bank subject to the regulations. Reserve systems are one such way. The MMT inspired suggestion of getting rid of most of the security shuffling and just going to permanent bank overdrafts at the central bank is another. Which of course gets rid of any ‘reserves’ completely – inverting the concept to ‘standing overdrafts’.

Central bank accounts are useful to banks. Settling in central bank money when dealing in a particularly currency is useful because it is cheaper and less risky than the Nostro/Vostro alternative of correspondent banking. But correspondent banking is still the default method of banking which banks can revert to in extremis.

“Which path are you referring to here?”

Settling across the books of the Fed in central bank money.

“Which of course gets rid of any ‘reserves’ completely – inverting the concept to ‘standing overdrafts’.”

Better clarify that. That’s where deposits end up held at the central bank as “digital cash”, replacing the current “insured deposit” schemes. If ‘insured deposits’ are retained with deposit accounts maintained at banks, then ‘reserves’ will get even bigger.

Neil, would you say that the ideas you have put forth here are or would be compatible with what MMT economists like Bill would say? I’m not saying there is anything wrong with proposing new understandings- just asking you to be clear when you go about it.

Some assertions you have made conflict with what I understand MMT to say.

“Settling across the books of the Fed in central bank money”

So in other places this is not typically done? Banks just credit each other Nostro/Vostro? And does this happen in the United States as well, or do the US banks typically settle at end of day using Fed Funds/Reserves?

Sorry for so many questions … I’m trying to clarify what you’re saying is different about the US practice compared to other systems. Any recommended sources to read up on it all?

@ Jerry Brown

“Some assertions you have made conflict with what I understand MMT to say”

Examples?

(Just curious).

Hi Robert. Just that MMT seems to place more importance on the role reserves play in settling accounts between banks and especially in the payment of taxes. In my opinion of course. I am not opposed to Neil explaining new ways of thinking about this- I just hope that he makes clear what are his ideas and what other MMT economists have said in the past. That’s all I was asking.

Neil is always worth reading and he often looks at things from a different perspective which I find to be very valuable in understanding MMT. And he knows this stuff better than I do.

Neil

Sorry for the delay in replying.

Maybe we are saying the same thing but from a different angle.

Letters of credit definitely happen but, as you said, assets and reputation make them possible (emphasis on assets).

Two small banks across the world interact with each other with relative ease because they have their Central Banks behind willing to supply settlement balances whenever needed.

Again, this is how a CB control the short term rate, manipulating reserves/settlement balances (quantity and currently via IOER).

It would be interesting to explore the detailed mechanics of a zero reserve banking system (Canada for example), at any point there are always reserve into the system anyway (especially now with QE in Canada).

Domenico Cortese: “Maybe we are saying the same thing but from a different angle.”

Yes. Neil distinguishes “central bank money” and “reserves”. I would not and think this sort of terminology just creates confusion, whether or not it is in use somewhere. If there is an account, which could ever have a non-zero balance (and ordinarily does) then there are reserves. Not just when there is some “central bank money” being “held in reserve”. And yes, there has been a widespread obsession spreading from monetarism about imaginary magical powers of the “held-in” reserves. And he is right that the correspondent banking is more fundamental.

Underneath, it is always “correspondent banking” that is happening, not just in extremis. Reserves, central bank money just provide a convenient agreed on, set measure of indebtedness facilitating correspondent banking transactions. Between private banks or between banks (or persons) and the state. It’s an important point. “Held-in” “Reserves” may lead to thinking of money as a thing, a natural magical commodity. Lends itself to the false idea of “medium of exchange” that one imagines reserves to be. As Mitchell-Innes said, “There is no medium of exchange”. To expand – he and Neil also I think – are saying that it is just the credit-debt relationships e.g. between banks, all the way down. “Reserves” being just relationships – accounted usually by uhh “bank accounts” – between a holder and the central bank or the state. Understood that way, they must by definition exist in state spending and taxation transactions. Or there wouldn’t be any transaction to transact. And equally, there is no logical necessity to use them in transactions without state involvement.

I don’t think it will do, though, to downplay the importance of “a convenient agreed on, set measure of indebtedness facilitating correspondent banking transactions” in a settlement process that has to operate perfectly, day after day, year in and year out. The pure correspondent-banking version of this failed in 2008 and stopped the entire world.

Some Guy …

1. Wouldn’t reserves be considered a “higher money” in the system since they are issued by the gov’t?

2. Are you saying that banks just let their correspondent balances grow indefinitely? Don’t they want to clear in that higher money at some point?

I’m reading a couple of papers about the implementation of zero reserve banking in Canada. I did not finish them yet but my understanding so far is that settlement balances (that is how they call reserves up north) are created “on the fly” by the BOC and request for them by banks are collateralized.

“are created “on the fly” by the BOC and request for them by banks are collateralized.”

Isn’t that the same as how the Fed’s discount window works?

It seems to me that it generally is true that a central bank can always find some excuse to create reserve balances on the fly if they want to. And the immediate banking problems occur or at least become very apparent when the central bank decides they don’t want to or can’t find that excuse. So actual reserves or the ability to access them become very important in crisis situations even if most of the time it isn’t all that crucial.

Really anyone can look at the US in late 2008 and see when and how the US government through its arm the US Fed, among other things, decided to make reserves available and save just about the entire US banking system. When it became clear there was a serious crisis there was nothing other than the government promising to back them up that could save them. It’s a shame the government did save most of them but that is a different story.

Like Mel said. The elaborations can only be blamed on me though.