I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

More fiscal stimulus – what shape recovery?

There is a lot of speculation in the financial press about the shape and timing of the recovery. As one article implied there is a veritable alphabet soup out there. Tied in with this speculation is the disagreement about whether governments have provided enough fiscal stimulus. The conservatives are mounting a vigorous campaign to choke off any more fiscal expansion. However, given how poorly the labour markets are functioning and the fact that they trail behind the output side of the economy by some quarters, there is a strong case to be made for more fiscal stimulus to be applied. I definitely see this as being required in Australia – a third package aimed directly at employment rather than consumption. Not many will agree with me though.

Over the weekend, Bloomberg ran a story which reported that two US professors were warning against a further US stimulus. This is a rival opinion to Paul Krugman who has said that a second stimulus is required. The conservatives in the US are ramping up their attack on the US government fiscal stance arguing that any further stimulus would be a waste of money. One Republican (from Ohio) was reported as saying that any more stimulus will put;

future generations under a mountain of unsustainable debt.

You know my view on the future generations myth – see recent blog – The myths of the ageing society debate and earlier blogs – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? – among others

Since the US economy went into downturn (December 2007) it has shed around 6.7 million jobs (the largest contraction in the Post World War II period. Further, in the second quarter of 2009, GDP dropped by 1 per cent the fourth quarter it has recorded negative growth. So quite a desperate situation.

Then there was the square-root theory of recovery that appeared in the UK Times newspaper on May 23, 2009. Relatedly, here is an economists’ forum that will make you laugh.

The Times article started with:

The question preoccupying economic policymakers is not the depth but the shape of the recession. The global economy is caught in a downturn as steep as the Great Depression. But in slashing interest rates, rescuing the banking system and pumping money into the economy, governments and central banks hope that recovery will be swift and sharp. And because economists typically prefer images to words, they describe that recovery as “V-shaped”: the downward stroke of the letter represents the collapse in growth, and the upward stroke the corresponding recovery beginning perhaps in the middle of this year.

But this the optimist’s view. Some economists think there will be an L-shaped recovery – that is, sudden collapse then virtually no growth for some years. This would of-course only be the case if the neo-liberals were able to white ant fiscal policy. The government can always generate growth if it is willing to push its net spending up to the point of non-government saving (anti-spending!).

Some think about U-shaped trajectories where the collapse wipes out productive capacity which takes some time to rebuild. The danger then is that the economy slumps into a W-shaped period or the so-called double dip recession typically because the government is bullied into withdrawing its stimulus too early.

But I thought the most creative “alphabet/symbol” to be invoked was:

… the “square-root shaped” recovery, corresponding to the mathematical sign. On this scenario, the recovery is initially sharp but then levels off.

The point of the Times article was not, however, to have a laugh at recession. It said that:

… there is a serious purpose behind it. Economic growth depends on confidence. John Maynard Keynes explained in the 1930s that businesses would invest only if they expected demand for their goods. If confidence were absent, then the economy might merely stagnate, regardless of how low interest rates fell. This is what happened in Japan in the “lost decade” of the 1990s, when no amount of monetary and fiscal easing could stimulate growth.

Well not quite. In Japan’s lost decade the only thing that maintained growth (albeit at low levels) and kept the escalation of the unemployment rate was the aggressive fiscal policy stance. The monetary policy initiatives were ineffective because Japan was stuck in a liquidity trap. Only fiscal policy could create growth in these circumstances and it did. The problem was that the public net spending was not sufficient.

The Times continues:

Keynes coined … the phrase “animal spirits” to signify this ingredient in economic recovery. These are not merely an expression of confidence in the future. They are more a shared sense of trust. The depth of the recession testifies to the waning of trust. In the boom, banks assumed that complex financial instruments had reduced the risks of lending. In reality, sub-prime mortgages and other asset-backed securities contaminated the financial system and brought down the real economy. Banks then hoarded cash rather than lent it, for fear of not getting it back.

Policy for the recession must therefore do more than expand the money supply and boost spending. It needs to give people a sense that it is rational to trust – to trust, for example, that banks will not be allowed to fail and that savings are safe. Policymakers must anticipate the ways that recovery might fall short, and convince the public that all is being done to restore growth.

The best way to do this is to stop the rise in unemployment. The deflationary impacts on aggregate demand of rising unemployment are profound. The shape of the recovery will depend, in part, on how quickly the government can reduce the unemployment. I don’t hold out much hope though that anything specific will be done in this regard that will be effective.

Remember GDP growth has to rise above 3 to 4 per cent typically (depends on labour force and labour productivity growth) before it starts arresting the rise in the unemployment rate (not to mention the rising underemployment that is occurring as firms hoard labour). It usually takes several quarters before GDP growth gets up to 3 per cent or so and by then there is an entrenched pool of long-term unemployed unable to compete easily with the new entrants who take the new employment opportunities.

It then takes years to eat into that unemployment pool as economies edge above the required rate of growth (to keep unemployment constant).

What does Australia look like?

You might like to first consider the following graph which I took from The Economist. It shows the recent downturn and recovery period for China, Singapore and South Korea and will bear on the pattern of recovery in Australia in the period ahead.

The Economist article says of the graph:

EARLY this year Asia’s economies were falling shockingly fast; now they are rebounding even more strongly than expected. Year-on-year growth rates conceal this bounce; to spot the turning-point, look at quarterly changes. Comparing the second quarter with the first at an annualised rate, South Korea’s GDP grew by almost 10% (though it is still down 2.5% on a year earlier); Singapore’s soared by 20% (3.7% down on the year). China does not publish quarterly figures, but economists think its GDP jumped by an annualised 15-17%.

So plenty of V apparent there. Strong fiscal interventions have driven these recoveries.

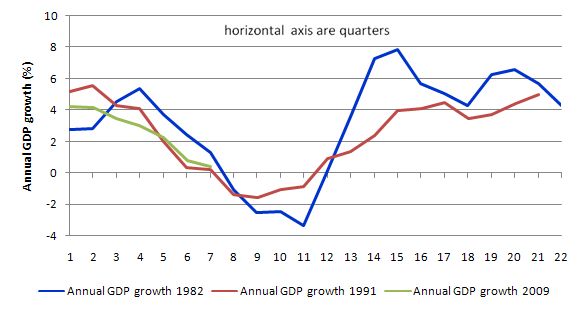

To give you an idea of what has happened to GDP growth in Australia during the 1982 and 1991 recessions I did some data analysis. The following graph captures annualised GDP growth 4 quarters before the peak GDP level corresponding to each of the downturns, then tracing the peak-to-trough period (8 quarters for 1982 and 9 quarters for 1991), and 12 quarters after quarterly GDP growth resumed again.

I have added the current period to the graph (green line) to compare the trajectory to the 1982 (blue line) and the 1991 downturn (red line). The graph provides a good picture of the way recessions begin and pan out from peak to trough and then into the recovery phase.

So before we get too excited we are following the trajectory at the same point in the cycle of the 1991 recession and the June 2009 quarter is expected to be negative by about 0.5 per cent (which will mean the green line will continue tracking the red line).

But the missing part of this story is what happens to employment growth. The following graph shows the annualised GDP and employment growth rates for the 1982 and 1991 recession compared to now. The time periods are as before.

What you see is that in the last two major recessions, GDP growth starts slowing before employment growth. Once the upturn starts, employment growth continues to decline for several quarters afterwards and trails the output growth. It remains negative for some years. That is the damage that recessions do. GDP growth bounces back much more quickly than employment growth and all the time unemployment is rising.

The current period looks to be following a similar pattern (don’t be fooled by the scale differences between the graphs) although the fiscal stimulus strategy may halt the downturn in its tracks. That is my current prediction. However, unless we get a significant output bounce back from the Asian V-recoveries shown above, then employment growth will continue to decline (maybe not as badly as in the previous recessions) and will take a long time to recover.

Further, while GDP growth may resemble a V-shape over the downturn and recovery phases, employment growth tends to be asymmetric. This was especially the case in 1991 when employment growth resembled a very flat tick mark. That shape was created, in part, by the underemployment that appeared for the first time significantly during that recession.

The current downturn is seeing underemployment rise significantly and this will mean employment growth will be very flat even if GDP growth is V-shaped.

In my view, the lessons from the past are that you have to keep fiscal policy expanding longer into the cycle and target employment creation. The lost output is bad enough, but the extended losses that are experienced in the labour market are devastating.

Conclusion

Imagine if the budget deficit was smaller and the government had have waited to see how bad things would get? It doesn’t bear thinking about. We would have probably plunged as badly as the other major economies.

The challenge is in my view to arrest the rise in unemployment by pushing on employment growth. My fear is that the private sector will linger even if a floor has been put in the downturn by the fiscal stimulus. Investment is not looking like rebounding any time soon.

In that context, the only way we can push on employment growth is for a third stimulus package in Australia to be squarely aimed at job creation. The lessons from the past downturns would make that a high priority.

The problem is where to create the jobs and who creates them ?

Then it just becomes a massive grab for cash where Sweet FA jobs will be created and we get another version of the present with a different title.

Alan,

Turning the army of unemployed into an army of graffiti removers would be a start. We’d get 6 months out of that for sure. The list goes on….

Tim,

The government would be stupid enough to pay the equivalent of a Picasso per item of grafitti removed to their provider / slave overseer of choice.

Why not just compensate the unemployed for their role in keeping inflation within the targeted band – and let the unemployed kickstart the economy when they go on a spending spree?

Dear Tim and Alan

Why not just employ unemployed artists to beautify our cities with lovely paintings and re-train the graffiti artists while being paid a living wage to produce beauty rather than the stuff we see on buildings (I know: tastes vary).

This would be an excellent Job Guarantee initiative.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

Excellent idea. I know of a few blokes who have a program like this completely costed and ready to go. Unfortyunately, Mr Hubbard (Julia Gillards gatekeeper) doesn’t like the idea of unemployed people being given a fair go and as a result has failed to respond with anything more than neo-liberal jibberish which is no different to the ideologically biased shyte Dutton and Andrews put forward previously.

Cheers, Alan

Job Creation always struck me as easy.

Invest in infrastructure, say a major road for argument sakes, and then define a limited contract that expires of above award wages (to entice qualified and quality individuals) which goes back to award levels upon completion or as it nears completion.

I know some industries attempt to work like this but then the people in other various fields (eg. engineer but one not working on the major road) ask for a pay rise because joe blow is getting $x doing this major road which can lead to wages spirally out of control. Then the next field does it and the next and so on. I’ve never understood why this happens since it should be simple enough to have it regulated in a contractual (work contract) context. I do not see why other workplaces are so pressured to inflate their wages unless of course they’re unaware that the money on offer for such a project is only for a limited time but surely that is easily fixed.

This is my longest comment contribution here, I hope it makes sense.

I hope this is not too far off topic – this article is arguing for more fiscal stimulus after all – but I can’t help noticing that commentators are beginning to say that business investment is beginning to take off again at a great rate, especially in Victoria (although it remains depressed in QLD).

Some of these people are the exact same ones who have been bellowing for the past 6 months or longer that government borrowing necessarily crowds out private sector investment.

I wonder what they are thinking about this? That the size of the spending thus far delivered has not been large enough to cause crowding out or that perhaps that government borrowing does not necessarily crowd out private investment after all?

My bet is on them yelling “quick! quick! get the budget back to surplus as soon as possible!”

Dear Lefty

The lobby groups that you are talking about have a litany of single sentence horror stories that they inflict on the public through their control of the media constantly. Sometimes they forget what they shrieked yesterday. When events overtake them … you will never see them reflect back. Why should they … by then they are onto their next campaign.

So union power one day; excessive real wages the next; lazy dole bludgers the next; but then it is excessive corporate regulation and tax burdens that appear to be the issue; which in turn, requires the government privatise all state assets built up over years by public investment; but never mind, by then the issue is the worry about the future and the imperative that the government runs surpluses; but suddenly, we have skilled shortages and need to cut training standards; and this is somehow tied into the danger of conceding to global warming warnings; which then leads them into a year of debt/deficits doom arguments and inflation, interest rate mountains and our poor kids having to pay it all back; which then segues into … as you note … the demand that government cut spending and get the economy back on track by running surpluses; but then unions are looking like wrecking the economy – which takes them back to excessive real wages and …

This pattern continually cycles through with mind-numbing regularity and we all give it credibility. More the fools us.

best wishes

bill