With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

Q&A Japan style – Part 2

This is the second part of a four-part series this week, where I provide some guidance on some key questions about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) that various parties in Japan have raised with me. I have so far given two presentations in Kyoto and today I am in Tokyo addressing an audience at the Japanese Diet (Parliament) and doing some interviews with the leading media organisations in Japan. Many people have asked me to provide answers to a series of questions about MMT, and, rather than address each person individually (given significant overlap) I think this is the more efficient way to help them to better learn and understand the essentials of MMT and real world nuances that complicate those simple principles. In my presentations I will be addressing these matters. But I thought it would be productive to provide some written analysis so that everyone can advance their MMT understanding. These responses should not be considered definitive and more detail is available via the referenced blog posts that I provide links to. Today, the questions are about the Green New Deal and the Job Guarantee.

Green New Deal and the Job Guarantee

Question:

What is the role of the Job Guarantee in a Green New Deal? How do they square with the fact that big infrastructure projects that might be associated with the GND are not suitable as automatic stabilisers, in the sense that they cannot be abandoned if there is accelerating inflation?

In their eagerness to tie the Green New Deal in with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), I have read several articles that put the Job Guarantee at the centre of government interventions that will be required.

First, I do not really like the term Green New Deal, particularly in a global sense, given its US-centric antecedents. The Wikipedia page for the – Green New Deal – shows how US-centric the notion has become.

Further, while FDRs New Deal was largely a cyclical program designed to deal with a collapse in non-government spending, the Green New Deal is not about resolving a cyclical shortfall in aggregate spending.

The various components of the New Deal were designed to advance what were referred to as the 3 Rs:

Relief – Measures to help the millions who were unemployed and homeless

Recovery – Policies to rebuild the economy that had suffered due to the Depression

Reform – Legislation and laws to create a fairer society

The reform component was largely in relation to the financial sector, which had created the Depression as a result of its poor performance.

The relief and recovery elements were what macroeconomists refer to as ‘counter-cyclical’ fiscal programs – working to redress non-government spending shortages, which leads firms to lay-off workers.

But the Green New Deal, as conceived, will be a structural program designed to significantly change the patterns of industry output, employment and the consumption patterns of households and firms.

It will have to fundamentally alter the line between government and market responsibility for resource allocation.

And it will require a fundamental reconfiguration of the concept of government putting the government at the centre of the transformations required.

I think that is appropriate because it will bring the responsibility for essential and planned action and the currency-issuing capacity together.

I outline my detailed views of the Green New Deal and MMT in this video presentation from September 23, 2019.

Second, instead of using the term – ‘Green New Deal’ – I prefer to focus on the human agency aspects, given we are talking about the impacts of anthropomorphic behaviour on the natural environment.

In that context, I would rather characterise the necessary transformation as a – Just Transition for the Future (JTF) – because I think if we can bring about meaningful and equitable change in human behaviour, we will solve the climate problems and save the world, as a by product.

This sort of causality chain is what I have in mind:

In the video noted above, I go into some detail of what the components of a Just Transition would look like.

I have been a long standing advocate of the introduction of a ‘Just Transition’ framework to ensure society deals with structural change, especially policy-induced changes, in an effective and equitable manner. We wrote about these issues well before the GND surfaced in the literature.

In this Report – A Just Transition to a Renewable Energy Economy in the Hunter Region, Australia (published 2008) – we demonstrated the major benefits to the Hunter and nearby Wyong regions (in NSW, Australia) from shifting from coal-fired power to a renewable energy economy but emphasised the need for the development of a ‘Just Transition’ framework.

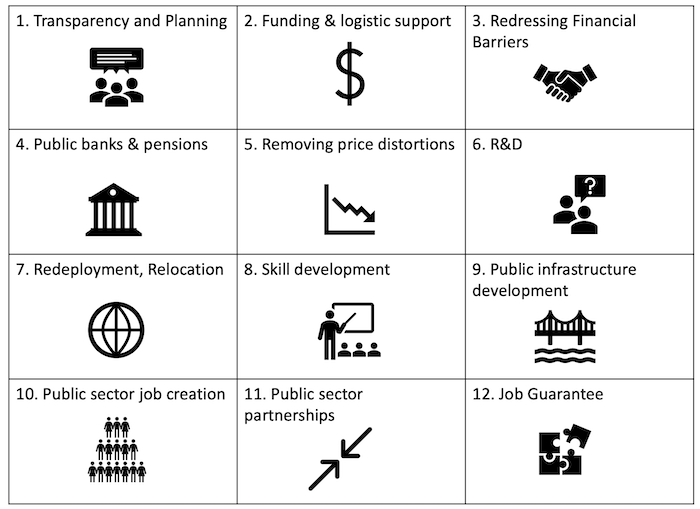

This Just Transition Matrix summarises what I see as the dimensions of such a framework. In the video cited above I go into chapter and verse of what each of the elements involves. See also the further reading blog posts below.

The point is that, in this context, the introduction of a national Job Guarantee, might in fact, be only a small part of a Just Transition framework to deal with climate change.

We have to understand that the Job Guarantee is not just a job creation program.

In MMT, the Job Guarantee provides macroeconomic stabilisation which is defined in terms of ‘loose’ full employment with price stability.

In normal times, it might not create or sustain many jobs at all.

And, importantly, it might not be part of a fiscal ‘stimulus’ program.

As Randy Wray and I wrote in a paper published in 2005 in the Journal of Economic Issues (Vol 39, No. 1, March) – In Defense of Employer of Last Resort: a response to Malcolm Sawyer:

The ELR approach is not equivalent to pump priming … with the ELR program in place, “loose full employment” is maintained no matter what the level of aggregate demand happens to be …

Importantly, one could envision a deflationary government policy (increased taxes and/or reduced overall spending) accompanying the introduction of ELR to reach and sustain full employment. We do not recommend such a policy (unless there were excessive overall demand), but it shows that Sawyer has mistakenly conflated ELR with Keynesian pump priming.

ELR and Job Guarantee were equivalent terms when we wrote that article. The MMT team now uses Job Guarantee, more or less exclusively.

And those that equate the inherent Just Transition framework with a Job Guarantee thus imply that the Job Guarantee would be central part of that stimulus program.

Which really abstracts from the fact that the Job Guarantee as a macroeconomic stabilisation framework.

In the context, the Job Guarantee will supplement the other policies to ensure there is a jobs safety net at the bottom of the labour market for the most disadvantaged workers.

The Just Transition framework will require governments create significant numbers of skilled and permanent jobs, which are not suited to a buffer stock status.

A Job Guarantee should rather be advocated for as a base case macroeconomic stabilisation framework rather than being tied up in the massive transition that will be required to meet the climate change challenge.

Even if there was no environmental imperative, we would enjoy dramatic gains by substituting an employment buffer stock approach to price stability for the current, very damaging unemployment buffer stock approach.

I would prefer the Job Guarantee to be seen as something desirable and quite separate to the complexity of a Green New Deal implementation.

We need to be careful not to conceive of the Job Guarantee as a panacea for all the labour problems that will arise as we make a Just Transition and we also do not want to try to make the Job Guarantee do ‘too much’, otherwise, we will be disappointed.

Further reading:

1. The Job Guarantee is more than a Green New Deal job creation policy (December 17, 2018).

2. The Green New Deal must wipe out precarious work and underemployment (August 8, 2019).

3. Modest (insipid) Green New Deal proposals miss the point – Part 1 (July 25, 2019).

4. Modest (insipid) Green New Deal proposals miss the point – Part 2 (July 25, 2019).

Question:

The Green New Deal by Ocasio-Cortez, UK Labour or Varoufakis etc. is receiving attention in USA or Europe. What is the theoretical and personal relation between MMTers and proponents of GND?

I cannot comment on the “personal relationships” between the people or groups mentioned.

But, in general, I do not consider the concept of Green New Deal is viable unless there is a simulataneous acceptance that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) provides a coherent response to the question “How will we pay for it?”, which is at the heart of resistance to the proposals.

The ‘How to pay for’ narratives always serve to derail a coherent discussions about the scope and magnitude of the transformation that will be necessary.

An MMT understanding allows us to dismiss the financial aspects of any likely transformation, and, instead focus on the real resource implications, which is core to MMT analysis.

In this respect, the Green New Deal will involve a massive transformation in real resource usage and, will in my view, require resolution to the most fundamental question of the organisation and ownership of the mode of production.

That is, it is unlikely that the transformation can be successfully completed within a capitalist system given the scope of the government intervention that will be required.

The elements of a Just Transformation framework will challenge the very basis of capitalist organisation that has morphed into a dominance of finance capital over industrial capital.

These elements will include:

- Social and economic equity.

- Well-paying and secure jobs for everyone who wants to work.

- First-class education and training, health and aged care.

- Government take back control of natural monopolies, strategic public assets etc.

- Community resilience and well-being for all regions.

- Stable and ethical financial system.

- 1st-class public infrastructure – transport, communications, utilities, etc

- Sustainable energy security.

- Meaningful and sustainable climate action.

So widespread nationalisation of what were once public utilities, elimination of most speculative financial activity, revamped education and training systems focused on societal well-being rather than feeding private profit, elimination of the precariat labour, elimination of speculative behaviour in energy production and the big carbon producers, and more.

MMT economists may differ about the specifics of these elements – in terms of importance and design features – but are at one with the view that the discussions should never be about the financial capacity of government to pursue and implement them.

We are united in eschewing the involvement of the financial markets in ‘funding’ the transformation, which many Green New Deal advocates think is an essential step towards viability.

Some of the groups mentioned in the Question fall into this trap, which is based on an erroneous understanding of the capacities of the currency-issuing government.

Question:

The merit of the Job Guarantee Program (JGP) is that the number of workers and hence the amount of fiscal expenditure under this program reduces automatically with economic expansion. But what kind of public works can be easily retracted without creating continuity problems? Is it possible to regulate the economic fluctuations automatically with a Job Guarantee?

In this 2008 Report – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy – we set out to provide a comprehensive and practical framework for motivating discussions about implementing the Job Guarantee.

It is clearly set out within the institutional structure of Australian government but the principles we established generalise.

This CofFEE Policy Report develops a new framework for the design of regional employment policy. It emphasises increased public sector infrastructure spending, the implementation of a National Skills Development framework and the introduction of a national Job Guarantee.

Our proposed new integrated policy framework will provide more effective ways to assist disadvantaged individuals into employment and advance sustainable solutions to persistent unemployment across regional Australia.

As one aspect of that framework, we proposed a – Job Guarantee – whereby the government operates a buffer stock of jobs to absorb workers who are unable to find employment elsewhere – whether that be in the private sector or the regular public sector.

The pool expands (declines) when private sector activity declines (expands).

The JG fulfills this absorption function to minimise the costs associated with the flux of the economy.

So the government continuously absorbs into employment, workers displaced from the private sector.

The “buffer stock” employees would be paid the minimum wage, which defines a wage floor for the economy. Government employment and spending automatically increases (decreases) as jobs are lost (gained) in the private sector.

It is clear that this overall aim has implications over the economic cycle and the cyclical nature of Job Guarantee jobs presents an operational design challenge for the administration of such a scheme and the design of the Job Guarantee jobs.

Job Guarantee jobs would have to be productive yet amenable to being created and destroyed in line with the movements of the private economic cycle.

To avoid disturbing private sector wage structure and to ensure the JG is consistent with stable inflation, the JG wage rate is best set at the minimum wage level.

The JG wage may be set higher to facilitate an industry policy function.

The minimum wage should not be determined by the capacity to pay of the private sector. It should be an expression of the aspiration of the society of the lowest acceptable standard of living.

Any private operators who cannot “afford” to pay the minimum should exit the economy.

The question though is questioning how a ‘buffer stock’ can operate effectively and be driven by the private economic cycle, yet still be logistically possible to organise into effective work effort.

While challenging this is not an impossible requirement for public policy to meet. The private sector does not have a monopoly on being able to mobilise a diverse range of resources and successfully complete thousands of tasks within a tight and complex schedule.

Note also that the private sector scheduling is in some sense much less flexible because it cannot afford to “inventory” workers who are (temporarily) unneeded.

Job Guarantee can employ workers even before precise tasks are assigned, helping to smooth transitions.

The cyclical nature of the jobs suggests that in designing the appropriate Job Guarantee jobs the buffer stock should be split into two components:

- A core component that represents the ‘average’ buffer stock over the typical business cycle given government policy settings, trend private spending growth, and a mismatch of labor force characteristics and employer preference.

- A transitory component that fluctuates around the core as private demand ebbs and flows.

The economic cycle fluctuations of employment are not nearly as large as people would like to believe. We have estimated that the total fluctuation between peak and trough in the Job Guarantee pool would perhaps be in the range of 25 per cent of the pool.

So there will be a fairly steady core of workers always in the pool. Nothing like from zero in a boom to millions in a recession.

Modelling can provide a guide to the ‘steady-state’ jobs that would be initially offered under the Job Guarantee scheme.

Administrators would then prioritise work allocations from a broad array of community enhancing activities. In this way, it is unlikely that any important function or service would be terminated abruptly, due to a lack of buffer stock workers, when the private demand for labour rises.

Thus, the design and nature of Job Guarantee jobs would reflect the underlying notion of a buffer stock.

This stock would, in turn, have a ‘steady-state’ or core component determined by government macroeconomic policy settings, and a transitory component determined by the vagaries of private spending.

In the short-term, the buffer stock would fluctuate with private sector activity and workers would move between the two sectors as demand changes.

Longer-term changes in the size of the average buffer stock would reflect discrete changes in government policy.

It is in this context that we argued for the existence of a stable core, which might change slowly and predictably as government policy settings change, and which would allow Job Guarantee administrators to more easily allocate workers to jobs.

Many of these core jobs would be more or less permanent. More ephemeral Job Guarantee activities could then be designed to ‘switch on’ when private demand declined below trend.

These activities would not be used to deliver outputs that might be required on an ongoing basis, but would still advance community welfare.

For example, Job Guarantee jobs in a particular region might be used to provide regular shopping or gardening services for the frail aged, to support the desire of many older persons to remain in their own homes.

It would not be sensible to make the provision of these services transitory or variable, and they would thus be provided from the core buffer.

Clearly, these services could be reassigned to become ‘mainline public sector’ work if a political shift in thinking occurred.

The structure of these jobs and the remuneration paid would however not be altered as a consequence of this political shift. Other ‘off-the-shelf’ projects would be undertaken or completed only when the Job Guarantee pool expanded sufficiently.

In the 2008 Research Report I cited at the outset of this answer, I noted that we sought to develop an inventory of jobs that satisfy several principles (see below).

These jobs would be accessible to the lowest skilled workers, generate benefits by way of meeting unmet demand for community development, personal care and/or environmental care services and more.

We sought detailed information from local governments on the type of jobs they could supervise that satisfied these criteria, including supervision and capital equipment costs and other relevant factors.

The local governments surveys revealed a myriad of community- and environmentally-based projects that could be completed if federal funds were forthcoming.

The JG workers would contribute in many socially useful activities including urban renewal projects and other environmental and construction schemes (reforestation, sand dune stabilisation, river valley erosion control, and the like), personal assistance to pensioners, and other community schemes.

For example, creative artists could contribute to public education as peripatetic performers.

The buffer stock of labour would however be a fluctuating work force (as private sector activity ebbed and flowed).

The design of the jobs and functions would have to reflect this.

Projects or functions requiring critical mass might face difficulties as the private sector expanded, and it would not be sensible to use only JG employees in functions considered essential.

Thus in the creation of JG employment, it can be expected that the stock of standard public sector jobs, which is identified with conventional Keynesian fiscal policy, would expand, reflecting the political decision that these were essential activities.

The exercise we carried to build an inventory of suitable jobs – both core and transitory – was specific to Australia – our institutional structures, cultures and specific community and environmental care needs.

The methodology, however, can be easily implemented elsewhere to create culturally- and institutionally specific job inventories to guide the introduction of the JG in any nation.

Further Reading:

1. When is a job guarantee a Job Guarantee? (April 17, 2009).

Conclusion

To be continued in Part 3.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“In normal times, it might not create or sustain many jobs at all.” I’m glad you said that, because when I first came to MMT properly I wanted to argue that here (UK) there could be too many essential jobs to do in the public sector and which a Labour government would need to create.

I asked a question in Kyoto on Monday.

The case of California was interesting.

Could you add that story to this series of articles?

There are so many jobs many of them onerous (the catering industry for example) which

currently pay minimum wage. Is it envisaged that large pay rises will be needed to encourage

people not to fall back on JG jobs.

Would this be just see an initial rise in prices or would the minimum wage need to rise

to account for price rises?

Is it all at best an educated guess?

Kevin,

This post was not clear, it said that the “minimum wage” the JG would pay is the minimum amount that would be the minimum that the society would consider the worst that a worker should have to live with.

Elsewhere Bill has said that this should be sufficient to be able to eat out once in a while at a sit down restaurant. It would have benefits like a paid vacation and healthcare. Obviously it needs to pay enough to be able to go somewhere on that vacation. It sounded like about $15/hr. in the current US economy plus the benefits.

Kevin Carol,

This doubling of the current minimum pay, and more with the benefits is why I have suggested that some form of UBI might be a good thing for a year or 2 as the economy settles down and gets used to the new situation.

This situation means that small businesses would have to pay their workers more, but it also means that there would be more people with the money to patronize the small business.

You might have noticed in this post where Bill said he has no sympathy for business that can’t survive the transition. He thinks they should not be given special rules and be allowed to fail.

In the US this may mean the farms can’t make a profit because the workers at harvest time will be paid too much. The farmer may find he can’t compete with cheaper imported food. And this will be bad for fighting ACC.

Kevin,

Shouldn’t a person be able to consume the types of goods or services he/she produces?

The value to the economy and society of a minimum wage is lost if the income it generates only allows a worker to pay all the rents being extracted from, just for the privilege of basic survival, and leaving no discretionary spending capacity at the end of the day.

“Catering”, “Cleaning services”, “Childcare”, etc.. are examples of jobs that entail a considerable amount of work. They can be considered as icing on the already pretty nice cake, wealthier members of capitalist society enjoy, “because they can”, as a result of the availability of labor at wages well below what would be considered to allow a decent standard of living . The wealthier folk can afford to pay more for their icing; and they do. The gap between what the labor is paid and what the owner receives for the minimal capital input required is, at a minimum, 60% in those businesses.

Most of these “industries” have never followed the capitalist model were some of the surplus income from the business is reinvested in tools to increase worker productivity which is what allows for higher labor wages while maintaining a profit to owners.

.

Dear sorata31 (at 2019/11/05 at 2:53 pm)

It was nice to meet you in Kyoto and then again in Tokyo today. Thanks for your interest in MMT.

The answer I gave was is covered in these blog posts:

California IOUs are not currency … but they could be! – https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=3145 – (June 30, 2009)

My letter to the Governor (arnie) – https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=3166 (July 1, 2009)

best wishes

bill

Kevin

A one-time adjustment in prices and wages across the economy, across the board, is not inflationary. Inflation is when prices keep going up. If the wage goes up from £15 to £16 to £20 to £25 to £30, then the private sector will have to match it. Yes, that will be inflationary,

However, the JG is anchoring the floor. We are raising the floor, and we are anchoring it at £15 as an example.

Pensions ?

Bill how will pensions work in this two tier system ?

Do people get a pension in the JG ?

Would the pension system have to have a complete overhaul so that those that leave the JG can take it with them ?

If we stop selling gilts could the Ways and means account be used instead to provide the pensions? After all it is just an overdraft at the central bank ?

Dear Bill

Thank you for introducing the blog posts at that time. (and autographing today)

I will translate these articles and post them to econ101jp.

https://econ101.jp/category/translation/bill-mitchell/

It seems to me that the removal of the unemployment buffer stock system is critical to both individual and collective mental health. I don’t see too manner rational collective decisions being made in the threatening environment created by sustained mass unemployment.

I fear that the climate emergency is too tangential to the fundamental problem to develop and sustain a national consensus on a return to economic sanity.

Derek Henry asked:-

“Do people get a pension in the JG “?

Interesting question, to which I too would like to know the definitive MMT answer.

But meanwhile I presume that employment in a JG job must necessarily enjoy parity with employment in a non-JG job insofar as accrual of *entitlement* to a basic national pension is concerned. Anything less would put JG jobs into a decidedly second-class category, which militates against the whole concept of the JG “remuneration package” (as a whole) establishing an equitable basic floor.

“Would the pension system have to have a complete overhaul so that those that leave the JG can take it with them”?

If the JG acted as a catalyst for that, so much the better – the “complete overhaul” being essential for its own sake in any case IMO.

Given the need to balance nominal spending growth against the real productive capacity of the economy, in a monetary economy, does not employing people on the gainful worker principle have a greater effect in reducing inflation than supporting surfers? I support the JG, but how does supporting surfers increase “produced means of production,” and is it not a sufficient supply of the latter that needs to be maintained to control inflation? I ask this not because I deny the buffer stock employment argument, but because I an not sure how MMT skeptics will accept the notion that money to surfers (or, say, skiers) is not inflationary.

Just to clarify i am very much in favour of a real living wage but interested what the implications

would be .Catering and i could have chosen shop workers would be examples of work which

presumably would need to pay above the new living wage to attract staff from a guarantied living wage shopping for the old or teaching guitar lessons in local schools and community.

In the uk many restaurant chains and high street shops have closed or are in difficulties it

is likely many would pass on the extra costs if they could.Would we end up with two effective

minimum wages the guaranteed state one and other employers having to pay more?

I know current minimum wage have had no effect on inflation.But as the growth of in work poverty

testifies (food banks and welfare top ups) we have never seen a genuine living wage as a minimum or a guaranteed job

I admit to being a cynic but i fail to be convinced of the Jg program being a macroeconomic

inflation anchor but i still support it . I see inflation in terms of conflicts both among and between

classes.By the way I am cynical that high levels of unemployment are an effective macroeconomic

inflation stabiliser it seems many countries especially developing ones have relatively high rates

of both unemployment and inflation as well as the more broad stagflation of the opec oil price

hike era.

Marian,

Sweeping up leaves or trash is also not producing something or service that the public can buy with their wages.

MMT doesn’t care about this. As long as the workers are doing something useful to the community it is all good.

As I see it, mostly all the stuff will be produced by private comp. with private workers.

OTOH, the Gov. will be producing services that the public can buy. Things like bus service, passenger train service, clean water, etc.

@Derek Henry. My understanding is that pensions should be a universal benefit and non-contributory – once freed of the notion that a pension is delayed wages. There is no reason why this sort of private saving should attract income tax relief.

@ kevin harding:-

“Would we end up with two effective minimum wages the guaranteed state one and other employers having to pay more”?

I take it as implicit in the JG concept that employers more generally *might* be obliged to offer above the JG remuneration-package level in order to compete for suitable applicants to fill their own vacancies.

But wouldn’t that depend in practice upon what other factors entered into the perceived “attractiveness” or otherwise of those alternative (to a JG job) job-offers in any individual case? We all know that many other factors than just remuneration play a part in the choices people make among alternative job-opportunities – once sheer desperation is removed from the equation as it wouid have been in a JG scenario.

Bill as we know is forthright in saying that employers whose businesses aren’t profitable enough (or aren’t being run efficiently enough) to be capable of paying their employees at least the national minimum wage (plus basic benefits) while still remaining viable ought rightly to go out of business. Which seems to me to be an inescapable corollary of espousing the JG proposal in the first place: anything less compromises it fatally before it even gets started.

“But as the growth of in work poverty testifies (food banks and welfare top ups) we have never seen a genuine living wage as a minimum or a guaranteed job”.

Very true – in respect of the most recent period (c. 1980 onwards). But in the preceding period (postwar up until around 1970 at least) we saw both – effectively albeit not by virtue of any formally-structured programme.

(Not sure what that tells us – just saying).

It seems like the JG is a political choice, rather than an integral part of MMT theory. It also has the feel of “just expand the public service” as well, but with low/no selection process (ie apply for job and you get one).

I can’t help but thinking that it will be difficult to prevent some “crowding out” of private enterprise from this. It’s just that the political choice from is “we’re fine with crowding those people out. Let the private sector fail.”

Probably would need some kind of temporary wage subsidy to allow for a smoother transition for business owners, given the large number of people on the minimum wage now. Giving employers a way to adjust would be useful.

Another measure to help prevent crowding out is to stop people stay in the “JG jobs” sector for too long. I could imagine this working with newstart where you have a “newstart phase” and if you cannot find a job after a certain number of months, to move into a “JG phase” for a year or so. Then back to newstart phase, etc and repeat the cycle.

Also, not sure how easy it is to say you have a “job guarantee” but then simultaneously place limits on how many of these jobs there are – what happens if the government gets “too many” people applying? won’t this lead to inflation?

@ vote for pedro,

No one else has replied. I’m no expert but I’ll try.

MMTers define inflation as *ongoing rises in prices*, note not an *increase in the money supply*.

I think they are not too worried about an initial rise in prices as the economy adjusts to the new system.

I think that there will be an initial rise in prices.

After the system is up and running, if it becomes necessary to cut the Gov. deficit and this leads to the private sector cutting back on the num. of workers, then the laid off workers will get a job in the JG program. Often this will pay them less, but never more.

As I understand the MMT JG program. It will *offer* a job to all. It doesn’t promise to let you keep that job if you don’t meet a minimum of level of characteristics. One part one the JG idea is that all the JG workers will have and be able to keep the necessary habits to hold a job. These include —-showing up everyday on time and not drunk, always calling in sick when sick, and looking like you’re working most of the time.

. . . If some workers can’t meet those requirements then the JG program will not be able to promise all employers that *all* JG workers are qualified for a private job. It seems to me that it therefore follows, that the JG will fire all workers who don’t show up on time and not drunk, who never call in when sick, and can’t look like they are working and getting things done. Such people would get a lesser welfare check, I guess.