Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Unemployment shame to increase!

In the Melbourne Age today (January 3, 2005), the forecasts of 18 economists for the year ahead. The group was overwhelmingly comprised of economists with vested corporate sector interests with only one academic economist being included. They make interesting reading given I also indulge in a bit of crystal ball gazing myself.

In an accompanying piece written by Josh Gordon (January 3, 2005) – Let’s get productive: economists – we read that “Private-Sector economists have thrown their weight behind calls for new productivity reforms to breathe life into the economy, urging the Government to use future surpluses to boost infrastructure, education, innovation and labour force participation.”

Well apart from the absurdity of the claim that the Government can ‘use future surpluses’ as if they are a stockpile the statement is interesting when one examines the forecasts produced by the economists.

On the former matter, please read the blog post – Macroeconomics 101 … not! (December 31, 2004) – to see why the proposition that the surplus is a stockpile is absurd.

To reiterate, the government does not need a surplus to spend. If it foreshadows higher spending than previously planned then the accounting statement that records the surplus/deficit will reveal a higher net spending aggregate than planned, other things equal. The government can spend what it likes when it likes.

But back to these statements about productivity.

Gordon claims that:

The Age economic survey found strong support for measures to lift the productive capacity of the economy, amid warnings that the extensive competition policy reforms of the 1980s and 1990s have lost their punch.

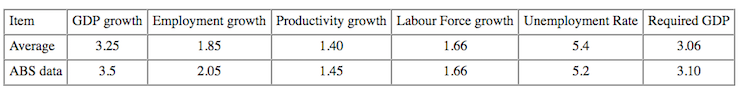

So what do the forecasts tell us? The following table compares the average of the forecasts with the actual average results over the last 3 or so years (for November using the Labour Force data and for September using the National Accounts data).

The ABS data shows the immediate past averages. GDP growth has averaged around 3.5 per cent since September 2001. So the economists think this will slow down a bit in the forthcoming year.

We can compute the implied estimate of labour productivity that the economists on average consider as the difference between GDP growth and Employment growth, which means in comparison to the 1.45 per cent per annum computed from ABS data since September 2001, the economists see a slight fall in labour productivity (1.40 per cent growth in 2005).

However, it is hard to see how the estimates are internally consistent. We know that the labour force has grown at around 1.66 per cent per annum over the last several years.

One reason the official unemployment rate is at 5.2 per cent is because over the last several years the GDP growth rate required to hold unemployment steady has been approximately 3.1 per cent per annum and actual GDP has averaged around 3.5 per cent per annum. So employment growth has outstripped labour force growth, although we know from the CLMI data published by CofFEE that an increasing amount of this employment growth is in part-time jobs that offer less than the desired hours of work.

The gap between hours offered and hours wanted shows up in the rising importance of underemployment in total labour underutilisation.

There are no labour force forecasts included in the survey so if we impose the 1.66 per cent per annum figure we would compute the average forecasted required GDP growth (sum of labour force and productivity growth) to be around 3.06 (say 3.1).

This would imply further reductions in the unemployment rate. So the average forecast of a rising unemployment rate doesn’t make sense.

The forecasts on average are internally inconsistent. In fact, I checked each individual forecast for accounting consistency and all of the forecasts were internally inconsistent (nothwithstanding the approximation inherent in this sort of ‘Okun arithmetic’). The only way the average could be consistent would be if labour force growth rate was to increase rather dramatically by around 17 per cent.

This is an unlikely event.

But if that is a reflection of the views of the group then it makes the claims that more microeconomic reforms are needed to boost labour force participation rather lame.

It may of-course suggest that the group as a whole think that the Government’s agenda to force the disabled and single parents into the Job Network structure, which will gather pace once it takes control of the Senate in July will significantly increase the participation rate in the second half of the year.

The employer groups will, of-course be behind all the upcoming reforms aimed at forcing reductions in the number of welfare recipients although they will not be proposing any reasonable government spending aimed at increasing employment growth commensurately via direct public sector job creation.

Their solution to providing more jobs will be to cut real wages and undermine working conditions generally. This will follow the US lead and transfer poor welfare recipients into the status of ‘working poor’.

The jobs growth if it does occur in the face of falling worker income would lead to even more insecure and low productivity jobs (given their estimates of the productivity and real wage outlook).

One forecaster thinks output growth will be 4.8 per cent over 2005 and employment growth will come in at 4.1 per cent. This suggests a miserly 0.7 per cent productivity growth rate over 2005.

The forecaster also suggests that the unemployment rate will drop to 4.9 per cent (down on the current official rate of 5.2). The sums don’t add up.

If labour force growth remains at around 1.66 per cent and productivity growth was to be 0.7 per cent then with a GDP growth rate of 4.8 per cent, we should expect to see around 2.4 to 2.5 percentage point drop in the unemployment rate.

Clearly these forecasts should not be taken seriously.

Further, the group predicts that real wages on average will grow by 1.4 per cent which is more or less equal to the implied growth in labour productivity.

This means they are predicting no cost pressures will be entering the labour market from the labour market. We will judge the comments of the employer groups in various wage tribunals over 2005 in this light. I bet they won’t be consistent with this prediction.

As an aside, the inflation rate is barely expected to move which means the group doesn’t consider the rapid rise in oil prices to be of any significance.

The last two oil price rises of this sort of spiking magnitude were followed by large recessions. I am leaning more to that outcome being closer to the mark than the relatively optimistic outcomes predicted by the ‘business economists’, who after all have a vested interest, by and large, in talking the economy up.

My consistently negative comments about the absurdity of running an economic growth strategy by running budget surpluses and thereby relying on ever increasing levels of household debt also condition my pessimism.

Conclusion

Overall, despite the fun with numbers the overwhelmingly discouraging thing about the whole exercise is the lack of outcry over the forecasted rise in the unemployment rate.

13 of the 18 predict that the unemployment rate will rise, 2 see no change and 3 think that unemployment will fall. On average the group the unemployment rate will rise over 2005.

If we consider those who think it will rise, then on average they think the rise will be around 0.4 per cent by the end of 2005.

So with a massive fiscal boost associated with the recent election campaign likely to impact on spending in early 2005 and their own forecasts of relatively strong domestic demand, the Australian economy is forecast to have rising unemployment.

In this context, why is there still talk about cutting back Government spending (to ensure a substantial surplus) to provide for the future.

The 11 per cent (and rising) underutilised workers need jobs and more hours of work now. For them the urgency of a stable income now is paramount. The way in which we have become inured to the outrage of persistently high unemployment is breathtaking.

Expect to hear a lot of attacks on the poor who rely on welfare in the coming months but little about the responsibility of government to ensure there are enough jobs available.

I support the push to increase labour force participation to allow those who can contribute to their families and communities the full rein to do so. But it is a sickening political game if the commensurate increases in employment opportunities are not also guaranteed by government.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2005 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments