Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

MMT and the external sector – redux

This blog post is written for a workshop I am participating in Germany on Saturday, October 13, 2018. The panel I am part of is focusing on external trade and currency issues. In this post, I bring together the basic arguments I will be presenting. One of the issues that is often brought up in relation to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) relates to the foreign exchange markets and the external accounts of nations (particularly the Current Account). Even progressive-minded economists seem to reach an impasse when the question of whether a current account should be in surplus or deficit and if it is in deficit does this somehow constrains the capacity of currency-issuing governments to use its fiscal policy instruments (spending and taxation) to maintain full employment. in this post I address those issues and discuss nuances of the MMT perspective on the external sector.

What we can agree on

There is now widespread understanding among those who have been introduced to MMT that:

1. There is a fundamental difference between the currency-issuer and the currency-user, such that the former has no intrinsic financial constraints on its spending. Such a government can always meet any liabilities that are denominated in the currency it issues.

This also means that such a government can purchase anything that is for sale in the currency it issues, including all idle labour.

Which means that the government chooses the unemployment rate. An elevated unemployment rate is always a political decision rather than anything that is forced on a nation by ‘market forces’ or the choice of individuals/households.

2. The governments ability to spend is prior to any revenue it might receive in the form of taxation. Taxation revenue comes from funds that the government has already spent into existence.

3. Central banks are monopoly creators of ‘central bank money’, while commercial banks create ‘bank money’ out of thin air – through “balance sheet extension”.

Central banks set the interest rate but cannot control the broad money supply or the volume of ‘central bank money’ in circulation.

This is because the central bank has no choice but to ensure there are enough bank reserves available given its charter is to maintain financial stability.

If cheques start bouncing because of a shortage of reserves then financial panic would follow.

This also means that the mainstream economics idea of ‘crowding out’, which posits that government borrowing absorbs scarce funds that would otherwise be available for private firms, is erroneous. Commercial banks will make loans to any credit-worthy borrower on demand. There is no scarcity of credit (loanable funds).

4. The National Accounts tell us that a government deficit (surplus) is exactly equal to the non-government surplus (deficit).

The non-government sector is comprised of the external and private domestic sectors. If the external sector is in deficit and the private domestic sector desires to save overall, then the government sector has to be in deficit and national income changes will ensure that occurs.

Which means that fiscal surpluses squeeze non-government wealth.

Further, the mainstream concept that fiscal surpluses represent ‘national saving’ is erroneous. A currency-user, such as a household saves (foregoes current consumption) in order to enjoy higher future consumption possibilities (via interest income on the saving).

A currency-issuing government never has to store up money in order to spend in the future. They can always purchase whatever is for sale in that currency at any time they choose.

5. The aim of fiscal policy is not to deliver a particular fiscal outcome (surplus or deficit). Rather, it is to ensure that the discretionary government policy position is sufficient to ensure full employment and price stability, given the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector.

If from a particular level of national income, the private domestic sector, for example, desires to save more overall and cuts its spending accordingly, then unless there is more net export spending coming in, the government will have to increase its deficit to avoid rising unemployment and a recession.

There is no particular significance in any fiscal outcome. Context is everything.

Even mainstream economists are starting to accept many of these propositions in the sense they now claim there is nothing new in MMT.

The external sector and sustainable policy space

However, there are still disputes about whether the external sector presents a terminal constraint on the government’s ability to maintain full employment and price stability.

MMT indicates that a flexible exchange rate regime maximises the policy space for government to pursue domestic objectives. Once a nation adopts a currency peg of any description (fixed exchange rate, dollarisation, currency board, etc) it loses its full currency sovereignty and compromises domestic policy aspirations.

Thus, the MMT preference for floating exchange rates is about removing constraints on policy that compromise the capacity of government to maintain full employment and price stability and deliver equitable outcomes to all.

To understand that, we must first develop a concept of sustainable policy space.

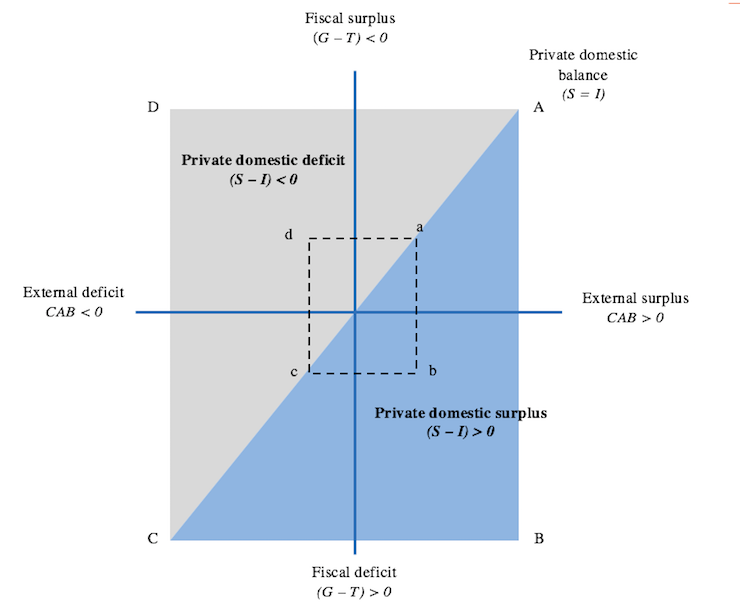

The well-known sectoral balances framework, which is derived from the national accounting framework can be depicted graphically (we develop this in detail in our forthcoming macroeconomics textbook).

The sectoral balances accounting statement is written:

(1) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

where S is household saving, I is private capital formation, G is government spending, T is taxation revenue and CAB is the Current Account balance (which is the sum of exports (X) minus imports (M) plus net external income flows (FNI)).

Equation (1) is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAB > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector, which must be saving overall (S > I).

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAB < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Consider the following four-quadrant diagram.

All points above zero on the vertical axis represent a government fiscal surplus (T > G) and all points on the vertical axis below the origin denote government fiscal deficits (G > T).

Similarly, all points to the right of the origin on the horizontal axis denote external surpluses (X + FNI > M) and all points to the left of the origin on the horizontal axis represent external deficits (X + FNI < M). While we shall refer to surpluses and deficits with respect to the sectoral balances, these balances should be understood as being expressed as shares of GDP.

Clearly, the origin of both axes denotes a position where all balances are equal to zero.

From Equation (1), we also know that when the private domestic balance is zero (S = I), then the government fiscal deficit (surplus) will equal the external deficit (surplus).

Thus, the diagonal 45-degree line shows all combinations of government fiscal balances and external balances where the private domestic balance is zero (S = I). We will refer to this as the SI line.

When is the private domestic sector in surplus or deficit?

At points A and C, there is a private domestic balance. Point B corresponds to a fiscal deficit (G > T) and an external surplus (CAB > 0). Thus the private sector must be engaging in positive net saving (S > I). Then between points B and A, and also B and C, net saving by the private sector is falling until private domestic balance is achieved at points A and C respectively.

Similarly, it can be readily shown that at D, the private domestic sector is net spending (S <I). Between points D and C and D and A, net spending by the private sector declines until private domestic balance is achieved at points A and C respectively.

We can generalise this knowledge and conclude that all points above the 45-degree line on each side of the vertical axis correspond to private domestic sector deficits and all points below the 45 degree line on each side of the vertical axis correspond to private domestic sector surpluses.

How would we use this graphical depiction of the sectoral balances to determine the feasible and sustainable policy space for a currency-issuing government?

First, for a sovereign, currency-issuing government, all combinations of the sectoral balances represented by the points in the four quadrants are permissible. With private sector spending and saving decisions combining with the flows of income arising from trade with the external sector driving national income, the government sector can allow its balance to adjust to whatever magnitude is required to maintain full employment and price stability.

For example, if the external account is in deficit and the private domestic sector is saving overall, then the drain on aggregate demand would require the government to run a deficit of sufficient size to ensure that total spending is sufficient to absorb the real productive capacity available in the economy.

Alternatively, the external account might be in surplus, which would add to aggregate demand, while the private domestic sector might be spending more than it is earning, that is, in deficit overall. In these situations the government would have to ensure it ran a surplus of sufficient size to ensure that the economy did not overheat and exhaust its productive capacity. The strong economy would be associated with robust tax revenue growth, which would help the government achieve its surplus. Discretionary adjustments in spending and taxation rates might also be required.

However, while these combinations of sectoral balances are permissible, we know that the private domestic sector cannot sustain deficits permanently. This is because the flows of spending which deliver deficits must be funded. Private domestic deficits ultimately manifest in an increasing stock of debt being held on the private domestic sector’s balance sheet.

This process of debt accumulation is limited because at some point the susceptibility of the balance sheet to cyclical movements (for example, rising unemployment) increases and the risk of default rises.

In the long term, the only sustainable position is for the private domestic sector to be in surplus. An economy can absorb deviations from that position but only for short periods.

Thus, it is only the area ABC (the blue-shaded area) that can be considered to be the sustainable policy space available to governments that issue their own currency.

If we were to impose fiscal rules on such a government (such as the 3 per cent threshold in the EMU Stability and Growth Pact) the sustainable fiscal space would shrink significantly.

Why is this important? An unconstrained government can always utilise the available space to ensure aggregate demand is sufficient to maintain full employment and price stability.

By definition, not every nation can run an external surplus because an external surplus in one nation has to be matched by external deficit(s) in other nations. While the external surplus nations have more policy flexibility when operating under a fiscal rule than external deficit nations, the fact remains that the allowable fiscal deficits may be insufficient to maintain the aggregate demand necessary to sustain full employment.

The policy inflexibility facing nations which run external deficits and simultaneously have to operate under fiscal rules becomes even more restrictive. When such an economy experiences a negative economic shock significant enough to drive the private domestic sector to reduce its spending and target a sectoral surplus, the extent to which the fiscal deficit can be used to absorb the loss of overall aggregate demand is very limited.

It is highly likely that such an economy will experience enduring recessions as a result of the artificial fiscal rules (restrictions) that are placed on its government.

The ‘Balance of Payments’ constraint and fixed exchange rates

I have dealt extensively with questions of the exchange rate and the open economy in relation to MMT previously. For example:

1. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1 (February 8, 2016).

2. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary? (February 9, 2016).

3. Balance of payments constraints (February 10, 2016).

4. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity (February 11, 2016).

The issues raised by MMT critics usually relate to the inflationary effects of exchange rate depreciation including the erosion of living standards via rising import prices and the destabilising impacts of currency speculation. Critics recognise that the depreciation may enhance trade competitiveness but then present elaborate formulae to show why that might not be the case (debates about Marshall-Lerner conditions, etc).

In effect, they argue that the sustainable policy space is much less than the previous diagram might suggest.

Taken together these concerns are bundled under a heading – balance of payments constraints.

So, while MMT proponents argue that the currency-issuing state has no financial constraints, critics argue that the capacity of a nation to increase domestic employment using fiscal deficits is limited by the external sector.

And they argue that these constraints have become more severe in this age of multinational firms with their global supply chains and the increased volume of global capital flows.

These critics also, often, erroneously believe that fixed exchange rate regimes provide financial stability and insulate nations from imported inflation, while flexible exchange rates undermine stability. History doesn’t support this preference for fixed exchange rates.

The Post World War 2, fixed exchange rate system restricted fiscal policy options because monetary policy had to target agreed exchange parities. If the currency was under downward pressure, perhaps because of a balance of payments deficit would manifest as an excess supply of the currency in the foreign exchange markets, then the central bank had to intervene and buy up the local currency with its reserves of foreign currency (principally $USDs).

This meant that the domestic economy would contract (as the money supply fell) and unemployment would rise. Further, the stock of US dollar reserves held by any particular bank was finite and so countries with weak trading positions were always subject to a recessionary bias in order to defend the agreed exchange parities. The system was politically difficult to maintain because of the social instability arising from unemployment.

If fiscal policy was used too aggressively to reduce unemployment, it would invoke a monetary contraction to defend the exchange rate as imports rose in response to the rising national income levels engendered by the fiscal expansion. Ultimately, the primacy of monetary policy ruled because countries were bound by the Bretton Woods agreement to maintain the exchange rate parities. They could revalue or devalue (once off realignments) but this was frowned upon and not common.

This period was characterised by the so-called “stop-go” growth where fiscal policy would stimulate the domestic economy, drive up imports, put pressure on the exchange rate, which would necessitate a monetary contraction and stifle economic growth.

While the ‘stop-go’ terminology was really born in the period of fixed exchange rates (Bretton Woods period), it is survived into the flexible exchange rate era (post August 1971).

Ultimately, Bretton Woods collapsed in 1971 because it was politically unsustainable. It was under pressure in the 1960s with a series of “competitive devaluations” by the UK and other countries who were facing chronically high unemployment due to persistent trading problems.

The fixed exchange rate history of the European Community, in various guises is illustrative of the problems encountered.

After the inevitable failure of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1973, most of the rest of the world decided that floating exchange rates were more desirable as it freed monetary policy from having to defend the agreed parities.

However, the EEC Member States persisted with various dysfunctional fixed exchange rate arrangements – the Snake in the Tunnel, the Snake, the EMS and then the ultimate ‘fixed exchange rate’ system – the common currency, in no small part due to their decision to introduce the Common Agricultural Policy in 1962.

The CAP introduced a complex system of cross border price fixes that would have been administratively impossible to manage without relative currency stability. As it was, the currency variations within the Bretton Woods system led the European Commission to introduce a complex system of so-called ‘green exchange rates’ or simply ‘green rates’, which sat underneath the official exchange rates.

Each one of these arrangements proved to be unworkable in the sense of allowing the governments to unambiguously advance the well-being of their people.

The Bundesbank historically ran a tight monetary policy because of its obsession with low inflation and this forced its trading partners to endure higher unemployment than they desired because they had to defend weaker currencies.

The weaker currency EEC nations – France, Italy, the United Kingdom (after 1971) – were forced to accept the restrictive Bundesbank monetary policy settings or else face major capital outflows. But they were continually up against currency pressures to devalue (under the fixed arrangements and with the Bundesbank more or less refusing to intervene symmetrically), so at times they had to push interest rates up well above the German rates to head of impending currency crises.

The history of the EEC is littered with these episodes.

The consequences were obvious – a recession bias, elevated levels of unemployment, and ultimately, increased speculative attacks on their currencies necessitating period devaluations following a currency crisis.

None of that tension has really gone away under the common currency. It is just that ‘internal devaluation’ has replaced the discretionary realignments pre-euro and central bank can no longer control capital flows in the way they did when their governments were sovereign.

Flexible exchange rates

After the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, most nations moved to a system of flexible exchange rates, with varying degrees of ‘management’ (dirty floats etc).

A flexible exchange rate frees monetary policy from having to defend some fixed exchange rate parity. This, in turn, means that fiscal policy can solely target the spending gap to maintain high levels of employment and other desirable policy objectives. External sector imbalances are then adjusted for by daily variations in the exchange rate.

While there is no such thing as a balance of payments growth constraint in a flexible exchange economy in the same way as exists in a fixed exchange rate world, the external balance still has implications for foreign reserve holdings via the level of external debt held by the public and private sector.

It is also advisable that a nation facing continual current account deficits, for example, foster conditions that will reduce its dependence on imports. However, the mainstream solution to such deficits actually makes this adjustment process more difficult.

Indeed, IMF lending and the accompanying conditions that are typically imposed on the debtor nation almost always reduce the capacity of the government to engineer a solution to the problems of inflation and falling foreign currency reserves without increasing unemployment and undermining public services, including health and education.

Targets to reduce fiscal deficits may help lower inflation, but only because the ‘fiscal drag’ acts as a deflationary mechanism that forces the economy to operate under conditions of excess capacity and unemployment.

This type of deflationary strategy does not build productive capacity and the related supporting infrastructure and offers no ‘growth solution’. And fiscal restraint may not be successful in lowering fiscal deficits for the simple reason that tax revenue can fall as the taxable base shrinks because economic activity is curtailed.

Moreover, the lessons of how the international crises of the 1990s and early 2000s were dealt with should not be forgotten: fiscal discipline has not helped developing countries to deal with financial crises, unemployment, or poverty even if they have reduced inflation pressures.

There are also inherent conflicts between maintaining a strong currency and promoting exports – a conflict that can only be temporarily resolved by reducing domestic wages, often through fiscal and monetary austerity measures that keep unemployment high.

The best way to stabilise the exchange rate is, within a stable political environment and well-functioning legal system, to build sustainable growth through high employment with stable prices and appropriate productivity improvements.

A low wage, export-led growth strategy sacrifices domestic policy independence to the exchange rate – a policy stance that at best favours a small segment of the population.

Flexible exchange rates and inflation

Critics argue that a nation with flexible exchange rates can ‘import’ inflation from other nations, which negate real income gains made through domestic expansionary policy. In other words, this is a revised version of the ‘balance of payments constraint’ on growth.

Through its impact on import prices, the exchange rate does influence the real value of the nominal incomes that are produced. The purchasing value of nominal incomes is the volume of real goods and services that an income recipient can purchase with those incomes. That depends on the prices of goods and services, some of which will be more influenced by movements in exchange rates than others.

Non-tradable goods and services will be much less influenced by exchange rate movements than direct imports. In many cases, these goods and services will have negligible exposure to exchange rate movements. The provision of many services, for example, will have little variability to exchange rate fluctuations.

The extent to which those movements in domestic prices are influenced by shifts in import prices arising from exchange rate movements depends on the degree of ‘pass through’ and the importance of imported goods and services to the overall basket that determines the workers’ material living standards.

The research evidence is clear – ‘pass through’ estimates are highly variable and depend on many factors including how much spare capacity there is in the economy, the degree of import competition, etc.

But that isn’t the end of the matter.

The second impact depends on how changes in overall consumer price inflation respond to changes in import prices. So ‘pass through’ might be high and rapid but the second impact low and drawn out, making the overall impact inconsequential.

So if imports are a relatively small proportion of goods and services included in the inflation measure, even if the ‘pass through’ is high, the overall impact on the domestic inflation rate will be small.

There is also the question of time lags – how long these separate effects take to impact. In many studies, the sum of the two impacts can take years to manifest.

It is also very difficult to come up with unambiguous estimates of these separate effects.

The coherent empirical research on this question suggests that ‘pass through’ effects are weak in most nations for which coherent empirical research has been conducted.

This blog post – Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary? (February 9, 2016) – discusses ‘pass through’ and the impact of exchange rate changes on inflation rates in more detail.

Estimates for Australia, which is a small, open economy highly exposed to exchange rate shifts, indicate that these exchange rate effects are very small and drawn out over time (Source).

Australia has historically endured large swings in its exchange rate. Between February 29. 1984 and July 31, 1986, the Australian dollar depreciated by 36 per cent against the US dollar.

By January 31, 1989, the exchange rate had appreciated by 48.6 per cent against the US dollar, a large shift in the opposite direction. This is a familiar pattern to citizens of Australia, a primary commodity producer.

Over the first period, Real net national disposable income rose just 3.3 per cent (per capita measure fell by 0.2 per cent), while real GDP rose 8.4 per cent and GDP per capita rose 4.7 per cent.

So even with a massive exchange rate depreciation, which followed major declines in Australia’s terms of trade, real per capita living standards barely fell using the Real net national disposable income measure and rose using the GDP per capita measure.

Three years later, Real net national disposable income had risen by 17 per cent (per capita measure rose by 12.2 per cent), while real GDP rose 12.6 per cent and GDP per capita rose 8.1 per cent.

It is also the case that the distributional impacts of those shifts are uneven. Buyers of expensive imported (luxury) cars suffer more than those who purchase the lower-margin cars. Those who take overseas ski holidays at expensive resorts face higher costs.

Australia regularly goes through these sorts of exchange rate swings but manages to be classified as among the richest per capita nations in the world. It is simply untrue that a flexible exchange rate system severely compromises the material living standards of workers.

Second, it is false to think that a flexible exchange rate regime is more prone to speculative attacks on a nation’s currency. If anything, the reverse is true.

When currency traders form the view that a government will have to eventually devalue a fixed peg parity to stem the consequences that accompany a chronic current account deficit they can easily hasten that decision by short-selling. It becomes a self-fulfilling inevitability.

And, in this context, the nation state has the capacity to impose capital controls if there are destabilising financial flows present. Iceland has demonstrated the effectiveness of using capital controls to stop the financial sector undermining currency stability through speculative capital outflows. Similarly, unproductive capital inflows can be subjected to direct legislative controls.

Moreover, the history of fixed exchange rates tell us that costs of defending the exchange parities (the recession-bias) tend to dwarf all other costs including fluctuations in price levels that might be sourced in exchange rate variability.

This is not to deny that a nation may have to take some hard decisions in relation to its external sector when it experiences a depletion of foreign exchange reserves or its currency depreciates against foreign currencies that it requires to purchase essential imports.

This is especially so if it the nation is reliant on imported fuel and food products. In these situations, a burgeoning external deficit will threaten the dwindling international currency reserves.

In some cases, given the particular composition of exports and imports, currency depreciation is unlikely to resolve the external deficit without additional measures.

As noted above, the depreciation may impart an inflationary bias to the economy. Moreover, depreciation leads to expectations of further depreciation and fuels the run out of the currency. There may be no interest rate that is high enough to counter expectations of losses due to depreciation and possible default.

The reality is that a nation facing a lack of ability to purchase imports, for whatever reason, has to either increase its exports or reduce its imports.

For less developed countries faced with currency crises, there is probably no short-run alternative but to urgently restore reserves of foreign currency either through renegotiation of foreign debt obligations, international donor assistance or default.

For an advanced nation, similar constraints might apply and a sudden shift in international sentiment against the nation or other financial assets denominated in that currency are no longer deemed as desirable, then adjustments in the flow of real goods and services sourced from foreigners are required.

And, as I explain in this blog – Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity – the limits for a nation are clear – if it cannot command access to real resources owned by foreigners the it must rely on the resource wealth it has for sale in its own currency.

But none of that reduces the financial capacity of the currency-issuing government to purchase whatever is for sale in that currency.

Further, it introduces a valid role for an international agency to replace the International Monetary Fund. A new agency could ensure that weak nations were always able to purchase essential energy and food imports.

Are current account deficits a problem?

We continually read claims that nations with current account deficits (CAD) are living beyond their means and are being bailed out by foreign savings.

In MMT, this sort of claim would never make any sense. A CAD can only occur if the foreign sector desires to accumulate financial (or other) assets denominated in the currency of issue of the country with the CAD. This desire leads the foreign country (whichever it is) to deprive their own citizens of the use of their own resources (goods and services) and net ship them to the country that has the CAD, which, in turn, enjoys a net benefit (imports greater than exports). A CAD means that real benefits (imports) exceed real costs (exports) for the nation in question.

Giving some real thing away is a cost. Getting some real thing is a benefit. Exports, by definition, involve sacrificing real resources and depriving a nation of their use. Imports on the other hand clearly involve receiving final goods and services where the real resource sacrifice has been made by the exporting nation.

In a world where we produce to consume receiving goods and services is better (real terms) than sending them elsewhere.

The only reason a nation would want to export and incur the costs involved is to generate a higher rate of return. Which means that the cost is best considered as an investment in generating benefits, which in this case, might be an increased capacity to purchase imports.

As noted above, being able to export is clearly particularly important for a nation that cannot feed itself or run electricity systems with the resources it has at its disposal without trade.

But there is another perspective.

Nations that export may desire to accumulate financial claims in the currency of the importing nation. A CAD also signifies the willingness of the citizens to ‘finance’ the local currency saving desires of the foreign sector. MMT thus turns the mainstream logic (foreigners finance our CAD) on its head in recognition of the true nature of exports and imports.

Subsequently, a CAD will persist (expand and contract) as long as the foreign sector desires to accumulate local currency-denominated assets. When they lose that desire, the CAD gets squeezed down to zero. This might be painful to a nation that has grown accustomed to enjoying the excess of imports over exports. It might also happen relatively quickly.

But in evaluating whether we should prevent that exposure by minimising CADs, we should understand that for an economy as a whole, imports represent a real benefit while exports are a real cost. Net imports means that a nation gets to enjoy a higher living standard by consuming more goods and services than it produces for foreign consumption.

Welfare is evaluated on the basis of consumption not production. This ties in with the view that external deficits automatically lead to a hollowing out of the industrial sector and the nation ends up a consumer rather than a producer.

The logic of the market is that consumers will demand what they think is best. It is true that if local production is lost to foreign nations as a result of trade competition, the consequences can be heart-wrenching for the dying manufacturing towns – as it was as agriculture waned some decades earlier and communities vanished.

While real living standards are based on access to real goods and services, and, at the macroeconomic level, a nation enjoys a material advantage if its real terms of trade are favourable (exports less than imports), a worker in a rust belt region who has endured unemployment as a result of cheaper imports coming from nations with lower labour costs is unlikely to be among those who benefit.

But there doesn’t appear to be a valid case to reintroduce widespread industrial protection where the rest of a nation’s consumers subsidise the jobs of a few who can no longer produce attractive enough products in their own right.

The challenge for nations entering a post-industrial phase is to implement what are called Just Transition frameworks to minimise the costs for the losers of industrial change and build pathways for workers in the declining areas into sectors that are growing. This is a fundamental responsibility for government and the evidence is, that in the neoliberal era, governments are abandoning that responsibility.

There are also nominal consequences of running CADs that need to be considered.

Foreigners (surplus nations) build up financial claims in the currency of the deficit nation. They might, for example, drive up local real estate prices or other strategic assets. Governments introduce foreign investment rules to militate against this propensity, although in many nations, these constraints are weak.

But the point is that the nation state can legislate whatever restrictions they like in this respect.

Alternatively, foreigners might sell all their currency holdings in one fell swoop and destroy the currency. They might. But then they would be deliberately creating massive losses for themselves, and history shows that this sort of behaviour is rare.

And if these funds end up in the hands of speculators the nation state can lock them with capital controls if it so chooses. Even the IMF supports that strategy these days and acknowledges it is effective. We noted above the way in which Iceland invoked effective capital controls during the GFC.

More problematic is that foreign interests may seek to use their financial clout to manipulate the political system and the public narrative view media domination etc.

Again, regulations can militate against that sort of trend. Strict campaign funding rules, media ownership rules etc are required to prevent these sorts of complications.

There is an additional consideration relating to nation-building. CADs tend to reflect underlying economic trends, which may be desirable for a country at a particular point in its development. For example, in a nation building phase, countries with insufficient capital equipment must typically run large trade deficits to ensure they gain access to best-practice technology which underpins the development of productive capacity.

A current account deficit reflects the fact that a country is building up liabilities to the rest of the world that are reflected in flows in the financial account. While it is commonly believed that these must eventually be paid back, this is obviously false.

As the global economy grows, there is no reason to believe that the rest of the world’s desire to diversify portfolios will not mean continued accumulation of claims on any particular country. As long as a nation continues to develop and offers a sufficiently stable economic and political environment so that the rest of the world expects it to continue to service its debts, its assets will remain in demand.

However, if a country’s spending pattern yields no long-term productive gains, then its ability to service debt might come into question.

Therefore, the key is whether the private sector and external account deficits are associated with productive investments that increase ability to service the associated debt. Roughly speaking, this means that growth of GNP and national income exceeds the interest rate (and other debt service costs) that the country has to pay on its foreign-held liabilities. Here we need to distinguish between private sector debts and government debts.

The national government can always service its debts so long as these are denominated in domestic currency. In the case of national government debt it makes no significant difference for solvency whether the debt is held domestically or by foreign holders because it is serviced in the same manner in either case – by crediting bank accounts.

In the case of private sector debt, this must be serviced out of income, asset sales, or by further borrowing. This is why long-term servicing is enhanced by productive investments and by keeping the interest rate below the overall growth rate. These are rough but useful guides.

Note, however, that private sector debts are always subject to default risk – and should they be used to fund unwise investments, or if the interest rate is too high, private bankruptcies are the ‘market solution’.

Conclusion

A national government should always aim to to design its fiscal policy with a view to the economic effects desired, rather than with a deficit or surplus target in mind.

While fiscal deficits are likely to raise living standards which will increase the CAD it should always be noted that all open economies are susceptible to balance of payments fluctuations. These fluctuations were terminal during the gold standard for deficit countries because they meant the government had to permanently keep the domestic economy is a depressed state to keep the imports down. For a flexible exchange rate economy, the exchange rate does the adjustment.

Is there evidence that fiscal deficits create catastrophic exchange rate depreciations in flexible exchange rate countries? None at all. There is no clear relationship in the research literature that has been established. If you are worried that rising net spending will push up imports then this worry would apply to any spending that underpins growth including private investment spending. The latter in fact will probably be more ‘import intensive’ because most LDCs import capital.

Indeed, well targetted government spending can create domestic activity which replaces imports.

Moreover, a fully employed economy with skill development structures, first-class health and education systems, and political stability, is likely to attract FDI in search of productive labour. So while the current account might move into deficit as the economy grows (which is good because it means the nation is giving less real resources away in return for real imports from abroad) the capital account would move into surplus. The overall net effect is not clear and a surplus is as likely as a deficit.

Even if ultimately the higher growth is consistent with a lower exchange rate this is not something that we should worry about. Lower currency parities stimulate local employment (via the terms of trade effect) and the distributional consequences tend to be more onerous for higher income earners.

These exchange rate movements also tend to be once off adjustments to the higher growth path and need not be a source of on-going inflationary pressure.

Finally, where a dependence on imported food or other essentials exists – then the role of the international agencies should be to buy the local currency to ensure the exchange rate does not price the poor nations out of these goods and services. This is preferable to the current practice of forcing these nations to run austerity campaigns just to keep their exchange rate higher.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

In your 4-quadrant diagram, the “45 deg. line” is not actually at 45 deg.

.

To be 45 deg. the 4 quadrants would need to be squares, and they are rectangles.

Steve_American

Dear Bill

A country has an interest in avoiding wild swings in its exchange rate. Every time that the exchange rises rapidly and drastically, the export industries have to shrink and the import-competing industries can expand. When it falls rapidly and drastically, the export industries can expand but the import-competing industries have to shrink. This is destabilizing.

A country has therefore an interest in combining a flexible exchange rate with controls on short-term capital flows. If a country has very one-sided exports, for instance 90% of its exports consist of oil, and if the price of its export fluctuates wildly, then it has an interest in setting up a stabilization fund.

Regards. James

I’ve been reading about MMT for a few years, primarily via your essays, your intro text and your book ‘Reclaiming the State.’ And this essay is instructive. That said, can you write more about

applied MMT economics? I think I get the general drift of what MMT is all about, compared to the mainstream economics, but I tend to think in terms of its application. For example, what of Trump’s tariff efforts? And poor Venezuela! You do a pretty thorough job critiquing the EU, so props to you there. I think your study of ‘framing’ the narrative for MMT would be helped by an approach that explains benefits created by applied MMT economics.

You write: “Taxation revenue comes from funds that the government has already spent into existence.”

I understand, however, that the largest amount of money is created by commercial banks in the process of extending credit/loans. I assume further that it is from this money that most taxes are paid/most tax revenue stems.

Why, then, do you not write:

“Taxation revenue comes from funds that the government has already spent into existence as well as funds that commercial banks have lent into existence?”

Why do MMT-texts tend to suggest that only money created by government provides the money that flows back to government as tax revenues?

Am I overlooking something?

Dear Steve_American (2018/09/26 at 6:19 pm)

Sure enough. It just goes to show I am a poor diagram maker!

Just imagine.

best wishes

bill

“If the external sector is in deficit and the private domestic sector desires to save overall, then the government sector has to be in deficit and national income changes will ensure that occurs.”

It seems to me that this statement is not strictly correct. If the private sector desires to save overall, it does not necessarily achieve savings.

Lector,

The commercial banks can create ‘money’ (liquidity) by creating loans (credit). But they cannot create new net financial assets because the asset (loan) is offset within the non-government sector by the liability (debtor).

Only transactions between the government and non-government sector can create or destroy net financial assets.

The government is also the monopoly issuer of the currency (notes and coins). The commercial banks can get access to that and distribute it (vault cash) but only by sacrificing bank reserves held at the central bank.

“…the largest amount of money is created by commercial banks in the process of extending credit/loans.”

By what metric? I see this claim made repeatedly but it’s only ever backed up by some central banker’s opinion.

Sounds like another myth promoted by Monetarists in my view.

If you compare the US outstanding credit balance to US federal spending over history you will find that substantially more spending at origination occurred from federal spending than bank lending.

Couple that with the fact that taxes only accrue against federal spending in the budget and that most of the $ remaining in the system are owed to the banking system it’s easy to come to the wrong conclusion relating to the origination of funds.

“This is preferable to the current practice of forcing these nations to run austerity campaigns just to keep their exchange rate higher.”

The current practice is the blueprint of neoliberal globalisation as the banks and financial elites cry for balanced budgets. Then brainwash the population that it all works like a household budget.

So the banks can allocate resources and the banks can be the main issuer of the currency. “We don’t want the government to fund public infrastructure. We want it to be privatised in a way that will generate profits for the new owners, along with interest for the bondholders and the banks that fund it; and also, management fees. Most of all, the privatised enterprises should generate capital gains for the stockholders as they jack up prices for hitherto public services.

This idea that governments should not create money from thin air implies that they shouldn’t act like governments. Instead, the de facto government should be Wall Street and the City of london. Instead of governments allocating resources to help the economy grow, the commercial banks should be the allocator of resources – and should starve the government to save the wealthy. Starve the government to a point where it can be drowned in the bathtub and which is what austerity and neoliberalism is really all about.

Allowing the commercial banks to control the money supply they then proceed to privatise the economy, they can turn the whole public sector into a monopoly. They can treat what used to be the government sector as a financial monopoly. Instead of providing free or subsidised schooling, they can make people pay for it to get a college education. They can turn the roads into toll roads. They can charge people for water, and they can charge for what used to be given for free under the old style of Roosevelt capitalism and social democracy.

The commercial banks can create ‘money’ (liquidity) by creating loans (credit). But they cannot create new net financial assets because the asset (loan) is offset within the non-government sector by the liability (debtor).

Only transactions between the government and non-government sector can create or destroy net financial assets.

The government is also the monopoly issuer of the currency (notes and coins). The commercial banks can get access to that and distribute it (vault cash) but only by sacrificing bank reserves held at the central bank.

This is the model that has failed and why Brexit happened and the rise of populism everywhere.

Free movement of capital.

Dear Derek Henry,

Thank you for your reply.

Unfortunately, I do not see how your points explain/prove that only government created money is capable of returning in the form of tax revenue.

Again, I may be overlooking something.

Can you spell out explicitly which facts and factors determine that all tax revenue must of necessity be money previously spent by government and cannot be money created by any other agent?

Thank you for your patience.

Dear paulmeli,

I refer to McLeay et al, who write

“Of the two types of broad money, bank deposits

make up the vast majority – 97% of the amount currently in

circulation.(6) And in the modern economy, those bank

deposits are mostly created by commercial banks

themselves.”

(Source: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf)

As for my principal question above, please be patient with me.

I do not see how your points explain or prove that only government created money is capable of returning in the form of tax revenue.

Again, I may be overlooking something.

Can you spell out explicitly which facts and factors determine that all tax revenue must of necessity be money previously spent by government and cannot be money created by any other agent?

Thank you for your patience.

Dear paulmeli,

I refer to McLeay et al, who write

“Of the two types of broad money, bank deposits

make up the vast majority – 97% of the amount currently in

circulation.(6) And in the modern economy, those bank

deposits are mostly created by commercial banks

themselves.”

(Source: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf)

As for my principal question above, can you demonstrate why tax revenue must necessarily be money previously spent by government and why it cannot be money created by any other agent?

Lector, here is my understanding of your question. The currency issuing government probably could decide what it will accept for payments of taxes. It might decide that gold or cows or labor would fulfill a tax obligation. It might decide that a promise to pay the government’s currency in the future, or upon demand, which is what bank created money is, would be acceptable. But usually in the present time, taxes get paid through the banking payments system and obligations between parties (various commercial banks and the government) are settled by transferring reserve balances at the central bank. Since the central bank is really an arm of the government, and is the only source of these reserves, central bank reserves really are ‘government created money’.

lector, perhaps I can help with this thought experiment. Let us suppose that we have a set of social groups that wish to amalgamate into a federal union, not unlike the 13 American colonies did in the 18th century. Each social group will have had its own currency. After the federal government has been set up, this currency will be worthless because it will be replaced by a national currency. There are two ways to deal with this. One is to set the value of the old currency to zero or to set it at a nominal value in relation to the new now national currency. The government can also spend directly to individuals and organizations in order to get projects it is interested in under way, such as bridges, schools, etc. Either way, the government has to be the first spender. This is because once the old currency is rendered valueless, no one has any money. Once these actions are done, the monetary curcuit is operational.

However, just because the government has created a new monetary system, it has to motivate organizations and individuals to use it. It does this by enacting fees and taxes which can be redeemed only in the national currency. This currency must be collected in order to pay said taxes or fees. Taxation could be said to be the initial driver of the national monetary circuit.

When it is said that the banking system is the greatest creator of credit/money, two things are sometimes conflated. One is the amount of credit/money created in a given time frame; the other is the number of instances of credit/money creation. Leaving out the issue of reserves, it could be said that there are more instances of direct credit creation by the retail banking system than there are by the central bank. This is simply because there are more of them. I left out the reserve system because each instance of credit/money creation by a retail bank is associated with an action by the central bank. They work together in this respect, so the picture of credit/money creation becomes quite complicated.

I don’t know if this is clear or answers your query.

@lector

“…I do not see how your points explain/prove that only government created money is capable of returning in the form of tax revenue”.

Income tax liability can and does accrue due to income from bank lending/spending but the tax cannot be subtracted from the credit balance, which can be reduced only through amortization.

One can’t, after borrowing funds to buy their house, go back to the bank and borrow the funds to make the payments, and in so doing reduce their outstanding balance. Nor can any other borrower reduce overall liabilities by providing you with the income to make your payments. Total outstanding liabilities increase no matter what.

Income taxes can only be subtracted from federal spending. There is no way to subtract them from the outstanding credit balance.

The funds necessary to extinguish credit liabilities can therefore only come from federal spending.

“”…the largest amount of money is created by commercial banks in the process of extending credit/loans.”

By what metric?”

Just looking in Wikipedia, the ratio of the M2 (cash and money waiting to be spent in current accounts) outweighs the Monetary Base (cash and bank reserves) in the U.S. now by a factor of 10+ to 3. This is less than I thought. I’ve repeated the 97% line, but I’m not sure now what basis I have.

“The challenge for nations entering a post-industrial phase is to implement what are called Just Transition frameworks to minimize the costs for the losers of industrial change and build pathways for workers in the declining areas into sectors that are growing. This is a fundamental responsibility for government and the evidence is, that in the neo-liberal era, governments are abandoning that responsibility.”

How do we calculate the total cost to the citizens of sovereign currency issuing nations, where successive neo-liberal infused governments have refused to apply a “Just Transition framework” based on their ideological principals?

It would be interesting to know how much of the household and business debt the world is swimming can be attributed to the abandonment of governments duty of care in this area.

As Michael Hudson points out even massive job creation won’t save some economies from that debt, and the cumulative loss of savings, which resulted from unreasonably long periods being deprived of expected personal income. Only a massive debt forgiveness to a level reflecting ability to pay can restore some normalcy.

Couldn’t a federal government use such a calculation to determine the size of the check it ought to send as relief of private debt that has that has accrued because of such misguided and improper behavior?

The central bank interest rate could then be taken to zero, or less, if needed to incentivize economic activity via commercial bank business lending shepherded by a government lead Just Transition Framework .

“[Why not] “Taxation revenue comes from funds that the government has already spent into existence as well as funds that commercial banks have lent into existence?””

Another angle, or maybe the same angle but spelled differently:

That’s not how lending works.

When I bought my last car, the bank arranged a 5-year loan. They did NOT go to the dealer and say “It’s being payed with a 5-year loan; you’ll get the money over the next 5 years.” They paid the dealer right away, with their money. I’m paying the bank over 5 years.

Similarly, if you borrow money to pay your taxes, the bank will cover your check to the Tax Authority right away, with money from their reserves. The loan deal between you and the bank stays between you and the bank.

“This is because the central bank has no choice but to ensure there are enough bank reserves available given its charter is to maintain financial stability.”

I may not agree on MMT in that aspect, if I could interpret it right. In my understanding, that statement may be valid for some countries but are not be valid to all.

I don’t agree because, in some countries, the central bank would supply reserves only in exchange for government bonds (direct transactions or repos) and nothing else, and it is not obliged to lend to banks in any other form, be it unsecured, collateralized by credit portfolios, or via bail outs or anything else.

Hence, in that countries, the only way the private sector can earn bank reserves is by working to the government and receiving a bank reserves transfer from the Treasury (or from other government agencies, depending on the institutional arrangements) or by selling government bonds (or giving it as collateral in repos) to the central bank (or to the Treasury itself, if it opts to buy back some government bonds). And by earning interest on governments bonds, repos and reserves, of course.

In that countries, if a bank faces a bank run and suddenly run out of bank reserves, checks would start to bounce, and it would go broke – and the central bank would not save it. What the central bank would probably do was trying to solve the problem as smoothly as possible, maybe by trying to find or facilitate a buyer for such broken bank or arranging its smooth liquidation – but not supplying bank reserves somehow.

On the other hand, I agree that, if the central bank controls the interest rates, it has no direct control over bank reserves balances, government bonds amounts, or any other monetary aggregate. If it controls the interest rates, the central bank has to option but to accommodate the level of bank reserves / gov bonds / repos / etc that the private sector wants at the interest rate. The exact way the central bank will do it depends on the institutional arrangements of the country (but usually central banks employ either repos or remunerated bank reserves for that purpose).

@Mel

I guess my point was how would one even do such a calculation? Funds are introduced through spending. By that metric, origination weighs heavily in favor of money creation by the state. From there, since all income taxes must subtract from G, most of what remains must be what is owed to the banking system. Simple enough arithmetic.

We can make a back-of-an-envelope calculation:

The sum of all deficits over history less Debt Held by the Public leaves maybe a couple trillion net $. I’m assuming bonds are not considered part of the official money supply. I did the arithmetic some years ago and maybe the difference has changed somewhat since.

Still, The ASTDSL series puts total liabilities (TCMDO) less government debt at around $44T.

2/(44+2) ==> 96% bank liabilities i.e. bank money remaining in the system.

I can see where they (central bankers/economists) may come up with that number but does it have any real world meaning or importance? I find it highly misleading as it promotes monetarist thinking over the capacity of the state to invest in our futures, and comparing spending to liquidity seems like a purposeful obfuscation.

Like the public debt/GDP ratio that has nothing to say of importance re the real world, it’s central bank/economist gas-lighting.

It seems that most of what we “know” is BS.

Bill. I’m glad you returned to this topic. I like and admire you guys. I consider Warren a genius. And I try to go along with, bring your thinking into my conceptualizations. But this external sector stuff, trade, current accounts – it always catches in my throat. I might say that in some ways it must run against my life experience. Here’s something at the center, for a closed economy, the world:

Total consumption + Total investment = gdp (production side)

gdp = Total consumption + Total Savings (income side)

So Total Consumption = Total Savings (I’ve seen this in your on-line book so it’s not just my idea)

A static situation where yearly, the amount of savings just satisfies desired investment.

Now suppose in a sector of the economy a higher level of savings is imposed, the portion of gdp allotted to consumption falls. Resources are freed. But we have a problem – desired investment has not increased and so investment does not increase. And this means that total savings have not increased – so in another area of the economy savings must decrease. And they will. Somewhere people will lose employment and productive facilities will slow or shut down. And so someone must spend. And as the govenrment spends the debt will rise. The only way it can not rise is if it’s productive investment. And how can that be assured?

Beggar thy neighbor. Trade war. I was listening to a conversation on public radio and the so-called experts, journalists and soybean council reps, and none of them could define trade war.

To me, large persistent trade deficits almost always indicate injustice and disease. Let me ask a few questions:

Large, Long term exporters can only do this by subjugation and subordination – people are denied the enjoyment of their efforts, aren’t allowed to work for themselves, so that the wealthy and powerful and gain more wealth and power in another arena. How do you make peace with injustice, the injustice of the exploiters when they use their leverage and power to take. The enjoyment of lower cost products isn’t enough for me. I don’t want to support slavery or bondage or exploitation.

It’s pretty obvious that the savings decisions elsewhere in the world impact, impose upon the savings decisions here. It has an impact on the liberty of people here. Some people are naturally inclined to build, manufacture. Why place them in competition with labor held in bondage? Don’t they have a right to use their natural talents and inclinations without undue pressures from outside.

You say “The logic of the market is that consumers will demand what they think is best. It is true that if local production is lost to foreign nations as a result of competition,…” Yes there has been a hollowing out. I follow the spot raw industrial price index. IN the US the economy has been growing while industrial production has been falling. We’ve lost a lot.

Markets, Competition. It’s funny you resort to neo-liberal thinking here. Yea there’s competition, but it’s raw power against raw power, looking for position and advantage. The wealthy and the powerful maneuver.

Persistent trade deficits can be imposed from the outside. All the chinese, or anyone need do is take their money here, take whatever discount necessary to acquire dollars, enlighten others about the good deals to be taken from their people in bondage, and buy or loan the dollars here. Trade flows determined by capital flows.

Well I’m tired out, like you. I hope I didn’t bruise your nose.

If cheques start bouncing because of a shortage of reserves then financial panic would follow. Bill

Otoh, if citizens could have accounts at the Central Bank itself, alongside those of banks, then a cheque drawn on an account there would only bounce if THAT account had insufficient funds.

So we could have TWO payment systems (besides physical fiat, coins and bills): An inherently risk-free, always liquid payment system consisting of individual, business, State and local government, etc. accounts at the Central Bank itself and the existing payment which must work through banks.

Jerry Brown, larry, paulmeli, Mel and Derek Henry – I want to thank you for taking up my question.

I can’t pursue your much appreciated contributions in this thread today or tomorrow, as I’m off on a business trip. But I shall certainly mull over your attempts at helping me.

In the past, I’ve had a number of issues when I thought MMT has got it wrong, while it actually was right. In every case, it turned out that I had not fully grasped or inadvertently distorted the MMT position. Frequently, the problem is that I tend to smuggle in assumptions that I’m not aware of myself and that are not part of the MMT take.

@ lector,

It really comes down to operation impossibility. Banks create bank money by creating bank liabilities (bank deposits). When a government initially sells a government security (bond) it only is for sale in the government’s currency (or equivalent central bank deposit). Whoever wishes to buy the government security must first therefore acquire the necessary government currency which can only come from the government via prior government spending (or from the central bank).

As Warren (and I’m sure Bill) has said… reserve drains (tax collection & government security sales) can only happen after reserve adds (government spending or central bank lending/purchasing/direct adds).

Lector: This may be the problem. You or I can pay taxes with bank money, by writing a check on our bank account. As far as you or I see, there is no difference between bank money and government money here. (Say that this tax check exhausts, closes our bank account, for simplicity) But that is not the end of the matter, which I think may be your assumption. After the federal government has accepted our tax check, the bank now owes the government.

It is as if the government now has our account at the bank. The government wants to be paid now, wants to close this account. The only thing it will accept from the bank as payment when it closes this account is federal money, reserves that it has earlier issued. If the bank does not have the reserves to pay up immediately, it will be in debt to the government, and the discount rate – determined by the government – is the rate that the bank will be paying the federal government on its “account”. If the bank can never pay this debt, it is eventually declared insolvent by the government.

Always, the government want’s its own money back. Rendered unto Caesar, as an ancient economist said.

lector, have a successful trip.

Some Guy, thanks to you, too, for your helpful explanation. I sense the penny is about to drop.

A very good summary.

I like the four quadrant graph and the 45 degree line representation of s=i. Helps a lot to understand the various combinations.

One concept I often struggle with is ‘investment’ and how one should conceptualise it in the sectoral balances. To what extent is is a build up of inventories when consumers stop spending leading to a contraction eventually as demand drops? To what extent is it productive investment, fixed capital formation etc? In what sense is it the other side of savings – does borrowing to invest create the savings or does the parsimonious act of saving provide the funds for investment? A blog on this would be helpful….

cs:

If we spend without purchasing consumption goods, that is presumably investment. Similarly, saving is income that is not spent consuming. As a matter of algebra, investment and savings are identical. Yet, this is an accounting identity and does not directly tell us causality. According to the mainstream theory, savings is the constraint on investment, akin to loanable funds thought. Accordingly, if the marginal propensity to save increases, more savings can be lent out. The main fallacy in this belief is that it confuses an increase in the marginal propensity to save with an increase in the volume of savings. If I save more money (increase my marginal propensity to save), I necessarily spend less money, which necessarily generates less income for those who would otherwise have been the recipients of my expenditures. Rather than savings increasing in total, this is a redistribution.

At an individual level, although it may appear that my saving has been a constraint on my decision to invest (suppose I buy capital goods), this ultimately raises the question of where I received my savings to “finance” my investment decision. It will be found to have been the prior result of investment decisions. If I work in the construction sector and investments are made in equipment, my income will be the product of that investment spending, which simultaneously generates an equivalent amount of savings until I decide to spend part of my income, but this then generates the multiplier effect and a dynamic change in leakages that eventually match the initial injections.

It is similar to the total spending = total income identity. Which causes which? While at the individual level it appears that I spend out of my income, I can theoretically choose how much I spend out of this income. But irrespective of my discretion, whenever I spend money I necessarily generate an equivalent income in the form of receipts. Hence, it is spending that determines income and not the other way around.

Bill,

In the long term, the only sustainable position is for the private domestic sector to be in surplus. An economy can absorb deviations from that position but only for short periods.

The above claim is illogical. Except for short periods when cyclical factors prevent it, private debt can rise for ever. Because as a long term trend, the amount the private domestic sector can afford to borrow will increase as long as one of three conditions are met:

1) Productivity increases

2) Interest rates fall

3) The inflation rate is positive.

Some businesses and individuals will desire to save, but in the long term it’s unlikely the private domestic sector will desire to net save unless the central bank uses usury to force it to.

In relation to Lector’s useful question and Some Guy’s excellent response can we say:

All money is ultimately Government money because when we pay for things, reserves move around so we are, in fact, using reserves all the time.

When a bank creates a loan, it later looks for reserves which are Government money (usually backed by repos-also a Government issued financial asset).

So maybe this distinction between loans and Government money is otiose? The main difference being, as Derek pointed out, that one is a net asset and the other a simultaneous asset and liability but all the payments are the movement of reserves, hence Government money.

I only appreciated this more recently when my friend Nigel Hargreaves pointed out to me that we are using reserves all the time and the ‘financial asset’ in ‘my’ account is not something parallel or separate from the reserves but ‘permission’ to use reserves.

Keyne’s seems to say this in his Treatise on Money:

‘The State-Money held by the central bank constitutes its “reserve” against its deposits. These deposits we may term Central Bank-Money. It is convenient to assume that all the Central Bank-Money is held by the Member Banks – in so far as it may be held by the public, it may be on the same footing as State-Money or as Member Bank-Money, according to circumstances. This Central Bank-Money plus the state money held by the Member Banks makes up the Reserves of the Member Banks, which they, in turn, hold against their Deposits. These Deposits constitute the Member Bank-Money in the hands of the Public, and make up, together with the State-Money (and Central Bank-Money, if any) held by the Public, the aggregate of Current Money. (Keynes, 1930 pp. 9-10) ‘

Not sure I quite get Keyne’s terminology here but he seems to support the point.

So maybe the artificial separation of this putative 97% from 3% cash is all unfounded?

This process of debt accumulation is limited because at some point the susceptibility of the balance sheet to cyclical movements (for example, rising unemployment) increases and the risk of default rises. Bill

I thought it was more fundamental than this in that bank “loans” (actually new bank liabilities for fiat*) only create aggregate principal and not the required aggregate interest thus guaranteeing at least some loan defaults.

And before anyone says that principal is a stock and interest is a flow, what if all interest income is not recycled into the economy as consumption and investment but instead some interest income is itself lent for even more interest?

*Since, except from their vault cash, banks can not lend their reserves to the non-bank private sector since the non-bank private sector may not have accounts at the Central Bank with which to receive fiat.

Hi Bill

I am just forwarding a comment from Warren Mosler.

If a bank doesn’t have ‘enough’ its Fed account is overdrawn, and an overdraft *is* a loan and booked as a loan if the bank does nothing. So it can be said that loans create both deposits and reserves as needed, all as a matter of accounting. There is no CB act of ‘accommodation’ anywhere in this process.

“If a bank doesn’t have ‘enough’ its Fed account is overdrawn, and an overdraft *is* a loan and booked as a loan if the bank does nothing.”

Well, there are many cases in which the account is simply not overdrawn. The bank will default in its payments and probably go broke (or at least face a severe stress period).

For example, Lehman Brothers account was not magically overdrawn.

So I have trouble in understanding what Mosler is trying to say.

Lehman Brothers was a real estate hedge fund disguised as a bank, so I’m not certain they even had an account with the central bank?

Matt B,

My point is that: The fact is that a bank always has some easy ways to invest in the government and earn the risk free rate (be it through remunerated bank reserves, repos or government bonds), but borrowing from the treasury, central bank or any other bank is another very different story.

If the bank doesn’t have good collateral (or sometimes even if it has) it will not be able to borrow. It may go broke. So, it is not symmetrical. It is easy to invest at the risk free rate, but not so easy to borrow at the risk free rate (or even the risk free rate plus a penalty).

I believe that Warren Mosler and Bill Mitchell are entirely aware of that…

Andrew Anderson,

“And before anyone says that principal is a stock and interest is a flow, what if all interest income is not recycled into the economy as consumption and investment but instead some interest income is itself lent for even more interest?”

Lending it out effectively recycles it into the economy. Indeed the flow of interest can be expected to increase the bank’s stock of capital which (because of the Basel requirements) is a constraint on how much it can lend (though usually just a secondary constraint; finding profitable customers to lend to tends to be the primary constraint).

Banks lending out money puts more of it into the economy; the flow of interest doesn’t alter that fact.

By definition, not every nation can run an external surplus because an external surplus in one nation has to be matched by external deficit(s) in other nations. Bill

What if the fiat given to foreigners in exchange for imports could ONLY be used to buy exports and labor from the importing nation or else be eaten away by negative interest at the importing nation’s Central Bank?

Then wouldn’t we strongly tend to have balanced trade for every nation that implemented that policy?

In other words, “Use our fiat to buy our exports and labor or lose it anyway.”

With Overt Monetary Finance, it might then only be necessary to implement negative interest on foreign owned reserves at the Central Bank to strongly encourage balanced trade?

Andrew Anderson,

Why would you want world trade obstructed by pointless (and probably unworkable) bureaucracy?

Do you see anything wrong with the situation where Australia net exports to China, China net exports to Europe and Europe net exports to Australia?

Why would you want world trade obstructed by pointless (and probably unworkable) bureaucracy? Aidan Stanger

What I’ve described would require no bureaucracy; just Overt Monetary Finance, which Bill favors anyway, and negative interest on foreign owned reserves at the Central Bank to encourage them to use those reserves or lose them. Where’s the bureaucracy?

As for my motivation, since exports need only pay for imports, and since it is controversial whether a trade deficit is good or bad, I was wondering why no one was advocating for balanced trade? Since every nation, in theory, can have balanced trade with every other nation? I supposed the answer would be like you said, that it could be a bureaucratic nightmare, and I sought an elegant solution instead.

And besides, it can be argued that only individual citizens have an inherent right to use* a Nation’s fiat for free, up to reasonable limits on account size and transactions per month, so negative interest on foreign accounts is a natural anyway,

*that is, in account form at the Central Bank or perhaps Treasury.

Aidan Stanger says:

Friday, September 28, 2018 at 11:04

If it turned out a country did not want to spend all its export earnings from a particular country on imports from that country, then it could swap its unused fiat for a more desirable fiat(s) rather than necessarily lose it to negative interest. And it could be assumed that roughly balanced trade would still be the result since the same negative interest rate would apply, only to a different account(s).

Since every nation, in theory, can have balanced trade with every other nation? aa

Informed by your question, make that rather: Since every nation, in theory, can have balanced trade with the rest of the world?

Matt, Andre- Lehman was an investment bank, not a bank. (Isn’t it wonderful how humanity comes up with such lucid terminology that makes all explanation superfluous? 😉 ) It did not have an account with the Fed, like a real bank. Goldman Sachs for instance, only became a bank with discount window access during the crisis.

Warren Mosler is often terse. I think the point is “this process” loans–>deposits–>reserves is (quasi)-automatic. If some bank were genuinely dedicated to insolvency – holding parties to burn its vault cash, say, eventually authorities might intervene and stop the fun. But it might take a while, it would require real regulatory intervention in the quasi-automatic process.

@ can people pay taxes with dollars created by banks?

IStM that “a dollar is a dollar is a dollar’. That is, there are 2 sources of dollars that make up the money supply; dollars deficit spent by the US Gov. in the past and dollars created out of thin air by banks making loans.

Dollars are fungible. They are the most fungible thing in the world. To me, the pool of dollars is like a pool of water. The water molecules can come from many reactions [burning H2, burning gasoline, burning methane, etc.]. In the pool they all get mixed together. It is IMPOSSIBLE to tell them apart. In the same way, dollars in bank accounts are a mix of the 2 kinds of dollars. It is impossible to tell them apart.