I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

The facts suggest Britain is not as reliant on EU as the Remain camp claim

I have been doing some analysis of British and European Trade patterns over the Post World War 2 period. They reveal some very interesting insights that are seemingly lost in the on-going war by Europhiles against Brexit. One of the recurring themes in the Brexit debate is the so-called importance of membership of the European Union to on-going prosperity of Britain through trade. What the data reveals is that British exports growth did not accelerate with accession to the EU in 1973 and after the introduction of the ‘Single Market’, British exports to the EU started to level off and then decline rather sharply. In other words, Britain has been diversifying its exports and is less reliant on the EU than it was say in the early 1990s. The data also shows that the creation of the Single Market hasn’t even boosted intra-EU or intra-Eurozone trade. Additionally, and laterally, the data suggests that the introduction of the euro has not expanded intra-EMU trade. The claims by the Euro-elites that it would were a major part of their justification for pushing through to the common currency. I consider this sort of evidence has been largely ignored by those in the Remain camp, who prefer to base their assertions on the highly questionable ‘forecasts’ coming from neoliberal-inspired ‘models’, which have so far demonstrated an appalling record of accordance with the facts. The data I have shown here doesn’t provide an open and shut case for Brexit. But it does show that the importance of EU membership to Britain’s prosperity is probably overstated and that Britain will prosper if its own policy settings are appropriate.

The anti-Brexit crowd are now leaving behind a litany of flawed statements relying on so-called ‘research’ that is quickly rendered ridiculous by the passing of time – that is, the evidence.

First, we had to the incompetent piece of propaganda masquerading as economic modelling from the British Treasury – HM Treasury analysis: the immediate economic impact of leaving the EU (released May 23, 2016).

The stated aim of the Treasury analysis:

… was to quantify ‘the impact … over the immediate period of two years following a vote to leave’

A more realistic interpretation was that the Treasury ‘analysis’ (using that descriptor rather liberally) was deliberately designed to bias the June Referendum vote towards delivering a Remain outcome.

I considered that Report in this blog post – Austerity is the problem for Britain not Brexit.

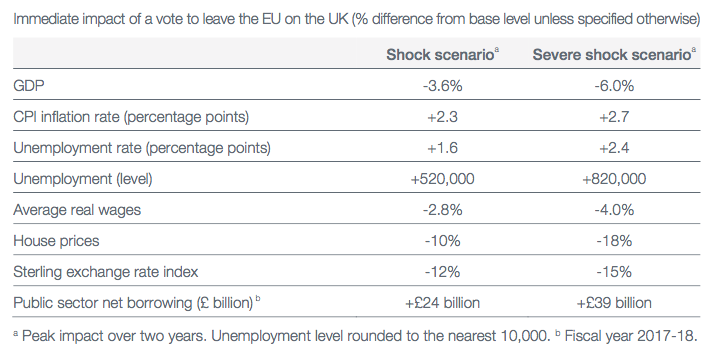

I discussed the major flaws in the modelling approach that produced their forecasts and concluded, categorically, that the scenarios they painted (outlined in the Table below) were far fetched in the extreme.

Just weeks before the referendum, the then-chancellor George Osborne, citing the report, warned that ‘a vote to leave would represent an immediate and profound shock to our economy’ and that the ‘shock would push our economy into recession and lead to an increase in unemployment of around 500,000’.

At the time, the ridiculous Treasury estimates presented in the Table above were complemented by a host of other estimates from other organisations (investment banks, multilateral institutions, etc) – all telling the same story. Doom from the outset and getting worse.

The stuck-record’ Guardian writer William Keegan wrote in his comment (September 4, 2016) – Brexit is truly daunting: this is the biggest crisis I have known – that:

Noises emanating from the Treasury and the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggest there is already panic in the ranks about a prospective deterioration in the budgetary position as a result of the likely impact on tax revenues of Brexit.

Time has a habit of exposing fakes!

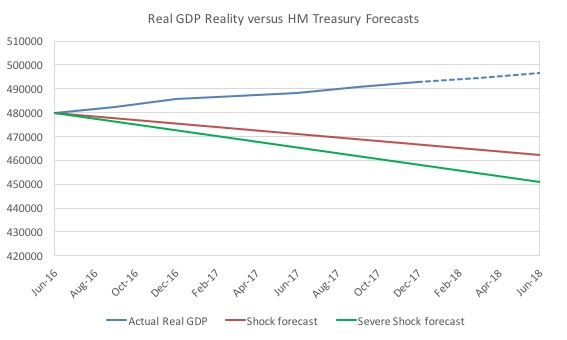

The following graph compares the actual course of Real GDP against the two claimed impacts (which I have linearised). The actual data is current until the December-quarter 2017 and the dotted line just assumes that the 0.4 per cent growth in that quarter continues.

It really doesn’t matter what we assume about the first two quarters of 2018, the reality will never be close to the fake estimates produced by HM Treasury.

With this degree of error, why should anyone ever trust further analysis put out by organisations using the same type of modelling technology.

GIGO – Garbage In, Garbage Out.

Official national accounts data from the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) shows that by the end of 2017, British GDP was already higher by 3.2 per cent relative to its level at the time of the Brexit vote – a far cry from the deep recession we were told to expect.

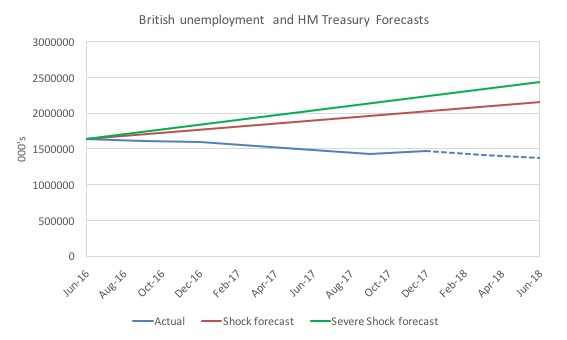

HM Treasury Predicted that the number of people unemployed would rise by 520,000 under the Shock scenario and 820,000 under the Severe Shock scenario by June 2018.

The actual unemployment is likely to be 1,368,885 million by June 2018, down from 1,640,373 in June 2016 at the time of the Vote. The Treasury estimates would have you believe it would have been 2,160,373 (Shock) or 2,440,373 (Severe Shock).

The following graph charts the actual path of British unemployment against the forecasts (based on an assumption that the current annual rate of decline is maintain for the first two quarters of 2018 – given the last quarterly estimate is for the December-quarter).

Similarly, the unemployment rate is likely to remain around its current level of 4.3 per cent (down 0.6 points) whereas the Treasury claimed it would rise to 6.5 per cent (Shock) or 7.3 per cent (Severe Shock).

By January 2018 there were 187 thousand fewer people unemployed that at the time of the Referendum – a 43-year-low. Economically inactive people – those who are neither working nor looking for a job – fell by their largest amount in almost five-and-a- half years.

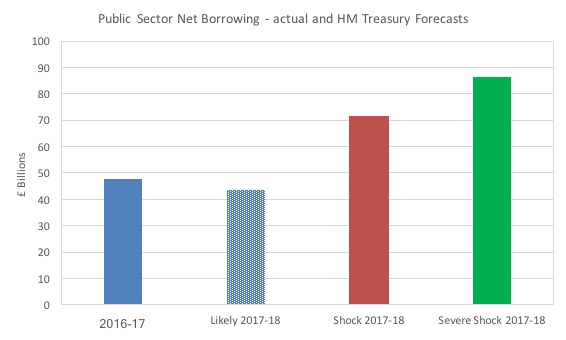

Finally, the next graph shows the actual Public Sector Net Borrowing (£ billions) in 2016-17 (£47.6 billion), the likely outcome given current trajectory for the 2017-18 fiscal year (£43.4 billion) and the Treasury forecasts under the Shock (£71.6 billion) and Severe Schock (£86.6 billion) scenarios.

Not even close.

Needless to say, that while inflation did indeed rise on the back of a weaker sterling – to a modest three per cent – it is now rapidly falling again. This, combined, with (a yet too) modest real wage growth, means that the former is starting to pick up with the latter.

Particularly embarrassing for the professional doomsayers is the data concerning the performance of British industry over the past two years, despite the uncertainty concerning the negotiations with the EU – thanks in no small part to the British government’s inane conduct.

The Economist article (February 8, 2018) – Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom concluded that:

… manufacturing is seeing its strongest growth since the late 1990s.

This view is supported by analysis from the British manufacturers’ Organisation.

In its April Monthly Briefing (released April 5, 2018) it said that:

1. “After a slow 2017, despite a roaring labour market and above target inflation, wage growth is finally beginning to pick up.”

2. “consumers think that this is the right period to save money and that their personal financial situation is going to improve in the next year.”

3. “Meanwhile the manufacturing sector set a new record with nine months of uninterrupted monthly growth.”

4. “Business investment has been revised up in the last quarter of 2017 and the current reading is for a quarterly expansion of 0.3% and an overall expansion of 2.4% in 2017”.

On Brexit, their assessment was that:

A year from now, not much will be different. If it all goes according to plan, the UK will officially be outside

the European Union tent but as we, most probably, will be in the first days of the status quo implementation period nothing will feel particularly different. The economic backdrop probably won’t have shifted too much either.

A far cry from the hysteria coming from the propaganda machines linked to the Remainers.

At least this assessment is grounded in what is actually happening with the data.

The improvement is largely due to a growing demand for British exports, which are reaping the benefits of the lower pound and improved world trade conditions.

The Remain camp – on both sides of politics – have now forgotten how bad the early Treasury and related analysis was.

They have a new ‘talisman’ now – the much-publicised leaked report prepared by none other than the British government’s Department of Exiting the European Union released in January 2018 – EU Exit Analysis Cross Whitehall Briefing.

The Briefing was meant to be confidential information for the ‘House of Commons Exiting the European Union Committee’.

I won’t consider all the political ramifications of the leak and the subsequent decision to make the document public.

Like the previous Treasury analysis (there were two documents published in 2016 – the analysis cited above of the effects over the immediate two-year horizon and the estimated longer run impacts) – the leaked document provided estimates of the supposed economic impact of Britain’s exit from the EU under various scenarios.

The scenarios include Single Market access through the European Economic Area (EEA), a free trade agreement outside of the Single Market and leaving the EU with no deal – and concludes that in all its possible forms Brexit would have a substantially negative impact on the UK’s GDP.

Estimates range from a 2 per cent lower GDP and 700,000 fewer jobs over the next 15 years to an 8 per cent lower GDP and as much as 2.8 million fewer jobs.

So a sort of horror story being maintained.

Even those on the Left are citing the leaked report claiming that as it was produced by Britain’s ‘pro-Brexit government’ it must be reliable – implying that it can’t in any way be suspected of suffering from an anti-Brexit bias.

See, for example, the article (April 12, 2018) – Is Labour up to a Brexit In Name Only? – by a commentator (who was associated with the Makroskop team), Will Denayer:

Why do I oppose Brexit? The following figures have been produced by Her Majesty’s pro Brexit government, so it’s hardly Remain propaganda.

His anti-Brexit argument invokes almost every Brexit-related myth in the Project Fear book: withdrawing from the European Union (EU) will be an economic disaster for the UK; ‘tens of thousands’ of jobs will be lost; human rights will be ‘substantially’ reduced; ‘principles of fair trials, free speech and decent labour standards will all be compromised’.

In short, Brexit will transform Britain into a quasi-fascist dystopia, a failed state – or even worse, an international pariah – cut off from the civilised world.

The intent of his entry into the debate is to criticise what he considers to be Jeremy Corbyn’s hitherto ambiguous Brexit strategy and calls upon him – and the Labour Party more in general – to take a radical pro-Remain stand.

This view is shared by most progressives across Europe but does not stand up to scrutiny.

The problem is that commentators who cite the leaked Report as a credible entry into the debate, ignore the obvious fact that the underlying modelling used to produce the estimates is riddled with neoliberal biases and is notoriously unreliable.

The workhorse models used to predict the economic effects are called Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models and the results from simulations are highly sensitive to the numerical calibration of the relationships in the models and the assumptions made about, for example, technology effects (‘returns to scale’).

The models are notoriously unreliable and easily manipulated to achieve whatever outcome one desires. I could calibrate and construct a CGE model to produce a utupian outcome for Brexit, but that outcome would be as flawed as the official estimates being produced.

The neoliberal biases built into these modelling exercises include assertions that markets are self-regulating and capable of delivering optimal outcomes (so long as they are unhindered by government intervention); that ‘free trade’ is unambiguously positive; that governments are financially constrained; that supply-side factors are much more relevant than demand-side ones; that individuals base their decision on ‘rational expectations’ about economic variables, etc.

Many of the key assumptions used to construct these statistical exercises bear no relation to reality. Simply put, the forecasting models – and mainstream macroeconomics in general – are built on a sequence of interrelated lies and myths.

I recall back in the 1980s, when the conservative government in Australia was trying to reduce the power of trade unions and cut workers’ entitlements, mainstream ‘think’ tanks using CGE models shows that cutting wages would deliver massive employment gains, stronger economic growth and better export performance.

But, by way of example of how one can ‘cook’ the results to get the outcome desired, when one examined the numerical calibrations of the academic models that were used, one found the employment sensitivity to real wage changes being used (the value of the coefficient) bore no relation to reality and the sensitivity to lost income from the wage cuts being virtually zero, when reality tells us the opposite.

So, of course, a real wage cut will generate massive employment gains under these ‘assumptions’. But the estimates are then not akin to anything that would happen in reality.

It is a similar story to the scandalous ‘mistakes’ made by the IMF in their modelling of the impacts of austerity under the second Greek bailout in 2012.

See this blog post – The culpability lies elsewhere … always! (January 7, 2013) – for detail on that scandal.

The point is that these exercises are not free of ideological bias and unless they are released for public scrutiny one has no way of knowing the extent of those biases.

The British government has refused to release the technical aspects of their CGE modelling, which suggests they do not want independent analysts like me examining their ‘black box’ assumptions.

However, given how embarrassing their previous ‘official’ forecasts have proven to be, the leaked document warns readers that:

Results for different scenarios are always assumption-dependent … Excessive weight should not be given to single-point estimates, given uncertainties, ranges of opinion on assumptions, global and sector trends and a variety of potential end states.

But having said that, they still claim that this type of “economic analysis provides us with the best available evidence base on which to draw a ‘broad’ directional picture”.

Well, the reality is that the forecasts are not “evidence” at all, for the reasons outlined above.

The document also emphasises that the CGE modelling was not used “pre-Referendum” as an attempt to distance the analysis from their disastrous Treasury modelling cited above.

But they still persist with the deployment of the so-called Gravity model of trade which is the standard mainstream framework.

They use gravity modelling to inform the CGE models.

Gravity modelling was first introduced in 1962 by the Dutch econometrician Jan Tinbergen and is motivated by two simple assumptions:

1. Countries with larger GDP levels will have more bi-lateral trade.

2. Countries that are geographically proximate will have more bi-lateral trade – lower transport costs, easier to gain intelligence to understand cultures etc.

When Tinbergen introduced this computational approach to understanding bi-lateral trade, goods trade dominated total trade flows and services trade required people to be in situ.

Hence the importance of transport costs etc.

But now, much trade occurs in services which can be delivered digitally and have zero transport costs.

There are also major issues in the statistical procedures used to generate gravity modelling estimates. I won’t go into these technical problems, but while there is a huge literature dealing with them, doubts remain on the veracity of the ‘numbers’ produced.

Trade patterns

The Remain camp take it as a self-evident truth that Britain has enjoyed huge benefits from joining the European Union and later with the introduction of the Single Market.

I considered that proposition in this blog post – Oh poor Britain – overrun by chlorinated chickens, hapless without the EU (February 1, 2018).

I showed that there is very little proof that the ‘Single Market’ has improved the relative performance of the EU15 economies (productivity, GDP per capita) against the US, the exemplar of a ‘single market’.

In fact, the dramatic shift that marked the introduction of the ‘Single Market’ was associated with a worsening the relative position of the EU15 against the US and Japan by not maintaining the closure that was occurring pre-single market.

To get a feel for how important the EU might be for British trade I have been digging further into the data.

Accessing, the very complex – IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) – produces some interesting insights.

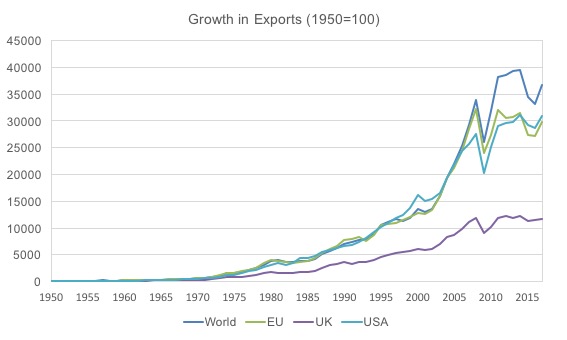

The first graph shows the growth in exports from 1950 to 2017 (where the index is set to 100 in 1950). The EU and the US have followed the pattern of World growth (being important components of it) but the UK has lagged well behind since the early 1970s – when it accessed membership of the EU.

The EU evolution is dominated by the export strength of Germany.

To put the previous graph in context, I added Germany and the PRC. The shift in world exports to China has been very significant.

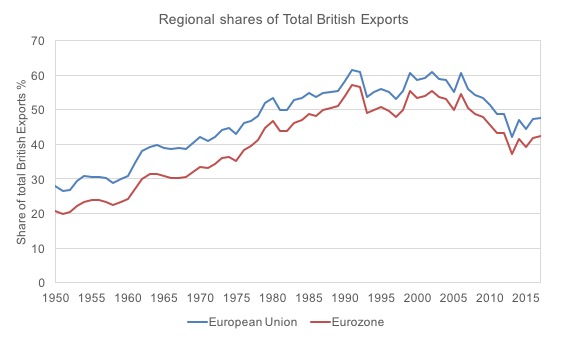

The next graph shows the regional shares of British exports (EU and EMU) between 1950 to 2017.

Two things are obvious:

1. There was no particular acceleration in British exports to the EU or to the nations now comprising the Member States of the Eurozone after it accessed membership of the EU in 1973.

2. After the introduction of the Single Market, twenty years later, the British share of exports going to the EU and the EMU flattened and after the 2005 (pre-GFC) started to decline rather sharply.

In other words, Britain has been diversifying its exports and is less reliant on the EU than it was say in the early 1990s.

Exports to China have risen from virtually zero in 1973 to 4.8 per cent of the total in 2017, while exports to the EU are falling towards the 1973 levels.

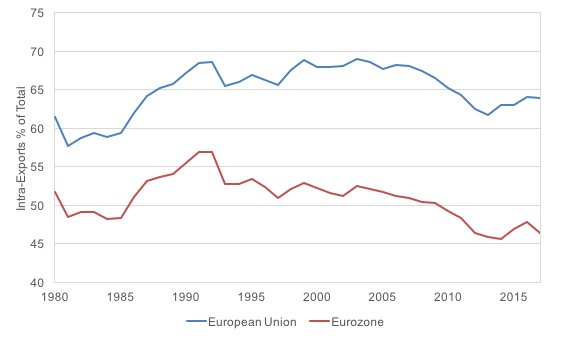

The data also shows that the creation of the Single Market hasn’t even boosted intra-EU or intra-Eurozone trade.

The next graph shows the percentage of total exports that go to Member States within the European Union (blue) and the Eurozone (red) from 1980 to 2017.

I ensured that the construction of the political blocs (EU and EMU) and the allocation of export flows was consistent with the rolling (expanding) membership of each bloc, although it doesn’t alter the conclusion if a constant membership was used.

The Single Market came into operation in 1992 about the time the data shows that trade within the EU (and between the Member States that would become the EMU) flat lined and has been falling since around 2005.

So even within a customs union, where tariff barriers are prohibitive to entry from foreign exports, the Single Market has not improved the British export performance – quite the contrary.

As the following graph shows, the share of the intra-EU export of the EU total export, after experiencing a steady rise throughout the 1980s, has effectively stagnated from the mid-1990s – that is, from the creation of the Single Market – until end of the 2000s, and has been on a downward trend ever since.

The same applies for the intra-EMU export of the total EMU export.

A Bruegel note (August 27, 2014) – Sharp decline in intra-EU trade over the past 4 years adds that:

… the Euro Area has been following nearly the exact same pattern as the European Union as a whole, suggesting the common currency might not have had the expected effect on trade between Euro Area members.

A further observation drawn from the IMF Directions of Trade database is that while global exports have grown by 5 times since 1991 and the advanced economies exports have grown by 3.91 times, the EU exports have only grown by 3.7 times and the Eurozone by 3.4 times.

Thus, in both relative and absolute terms the Single Market has not had the major postive effect that the anti-Brexit lobby would have us believe.

It is, of course, always possible that without the Single Market, outcomes would have been much worse. But that conjecture would be difficult to sustain.

Conclusion

I consider this sort of evidence has been largely ignored by those in the Remain camp, who prefer to base their assertions on the highly questionable ‘forecasts’ coming from neoliberal-inspired ‘models’, which have so far demonstrated an appalling record of accordance with the facts.

The data I have shown here doesn’t provide an open and shut case for Brexit.

But it does show that the importance of EU membership to Britain’s prosperity is probably overstated and that Britain will prosper if its own policy settings are appropriate.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“So even within a customs union, where tariff barriers are prohibitive to entry from foreign exports, the Single Market”. Think you missed the end of the sentence there 🙂

Also given the euro-area reliance on exports to the UK and, due to the fiscal compact, the inability to substitute these income flows with fiscal expansion, it’s dumb the UK doesn’t drive a harder bargain. But then the negotiators probably don’t know MMT.

Great article debunking the fear mongering around Brexit which raises the question, what was the point of Brexit? Were there any significant disadvantages to being in the EU than outside of it?

Dear Justpointingatypo (at 2018/04/16 at 11:58 am)

Thanks. It was a test – fill in the obvious conclusion! (joking).

Fixed now.

best wishes

bill

Detailed analysis. Well done.

It captured particularly my attention this part [The actual unemployment is likely to be 1,368,885 million by June 2018, down from 1,640,373 in June 2016 at the time of the Vote. The Treasury estimates would have you believe it would have been 2,160,373 (Shock) or 2,440,373 (Severe Shock).].

In a world where nobody does something from the beginning until the end (a computer, a cup, and so on) it is a kind of natural that temple like structures such European Union (EU), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Transnational Corporation and so on will emerge.

UK has to be integrated with some temple if the temple is not EU then will be something else.

The persons running the temples and those attending the temples stopped to communicate effectively. The traditional 1-1 communication “does not” exist anymore now it is “all” n-n communication. We find in 1-1 communication persons of “REMAIN” using “LEAVE” arguments and vice-versa. Cambridge Analytics worked with Brexit and with DT but failed with Le Pen. The things are to much complex for our little brains, specially for those who have not access to intelligentsia.

Articles such as this one are important because they help us to take the noise away.

“Were there any significant disadvantages to being in the EU than outside of it?”

Eliminating article 123 of the EU treaty for starters. Inability to manage borders for another. And removing the rights of corporations to override acts of parliament (the appeal to higher law). All of which you really need to implement a Job Guarantee in a currency area.

The question is rather the reverse. Is there any point in the EU? It serves no purpose other than a focus for those who still pursue the fantasy of globalism.

“UK has to be integrated with some temple”

Specifically it must not if democracy is to work effectively. The larger the grouping the more network effects lead to the tyranny of the vocal minority.

The future lies in highly cohesive areas, loosely coupled together. Which is how you build any system you want to survive the brickbats of continuous change.

I understand your point.

If you have an amount of population which is (1) small, (2) is not growing, (3) with no migration (4) … you can think about democracy and similar concepts. However, if you have a large amount of population and growing ochlocracy might the rule of the game. The persons do not communicate effectively.

In addition to what Neil said, I would add The Maastricht Treaty, which imposes limits on the size of fiscal deficits and cumulative debt; restrictions on state aid to industry; restrictions on our VAT rate, and probably other things.

Theoretically, I think it also meant that we were supposed to have the intention of joining EMU, as soon as we had met the “convergence criteria”. Fortunately Gordon Brown put the brakes on that one, or no doubt the criteria would have been fiddled (as they were for Greece and Italy) to let us in.

I didn’t hear any of the above being discussed during the referendum campaign, perhaps not surprisingly, as they become much more meaningful when looked at through an MMT lens, which of course most politicians don’t do.

@Bill: Technically, William Keegan is an Observer writer, although this is not obvious from the online article, since Observer and Guardian articles both appear on the Guardian website. The Observer is, in effect, the Sunday Guardian (although the people on The Observer probably would not describe it like that. 🙂 ). In his profile on that website, it says “William Keegan is the Observer’s senior economics commentator”, but I won’t give a link, since that page also links to a lot of his anti-Brexit articles. 🙂

I think the easiest way to disprove the gravity models is to look at the UK and Netherlands relationship with trade. Huge amounts of that trade are artificial in nature, it is about the huge container ports in Holland that were built from the Arbitrage of EU Tariffs to the rest of the world.

You have to ask the question what the rationale for sending it to a large hub is, as they essentially sail past most of Europe only to distribute it later. What effect that had on Greece, that once had the road to East.

Agreed that we can’t get one assumption for any of these models. Although inflation looks like it mirrors treasury expectation, there are stronger underlying causes to UK inflation than just currency weakness.

I don’t think they can ever release the assumptions and drivers of these models. Perhaps best that they don’t, and then we can move on.

“A research academic from the University of Cork, Will Denaye.”

Well there’s your answer for you. Brexit will have a severe symbolic impact on the Irish. It’ll take Northern Ireland out of the same jurisdictional/economic sphere as the Republic. If the UK leaves the customs union too, there will probably be checkpoint’s on the border. All of this isn’t good news given what happened during the Troubles.

Of course one solution if for Ulster to become part of the Republic but at the moment Ulster’s Unionist population remains a majority in the North. The other solution would be for Ireland to leave the EU and negotiate with the UK on a bilateral basis but that’s not going to happen either.

The Irish really don’t want Britain to leave the EU.

“The other solution would be for Ireland to leave the EU and negotiate with the UK on a bilateral basis but that’s not going to happen either.”

The third solution is to remember protocol 20 – which incorporates the Common Travel Area into the EU treaty.

Since it is very difficult to have a border down the middle of a free movement area, that means if the EU doesn’t want a FTA with the UK, they really need to have one between Ireland and the UK. Not only that but the GFA (which allows NI citizens to be Irish citizens) really requires Ireland to implement one or they’re likely to fall foul of the human rights charter on citizens freedom of movement.

So it’s less that Ulster becomes part of the republic – which doesn’t have public support – but more that Ireland has committed itself via the GFA to remain part of a British Isles free trade area.

As of april 26th the movie “De achtste dag (The Eighth Day)” is coming out in the Netherlands from director Yan Ting Yuen. This movie is based on the rescue operation of FORTIS / ABN AMRO, European leaders from and takes us back to the seven most exciting days of 2008. In ‘the eighth day’, they share their deepest insights, frustrations and fears about the crisis. How did it work in the back rooms of power? And where are we now, ten years later? Is it really going as well as we think? Can we go to bed quietly? That is still the question, says Bos and Trichet. “One of the biggest reasons for the crisis was the high debt. Now they are even higher than in 2008. The risks of a major crisis are perhaps even greater than before 2008. ” The trailer looks great, but it is unfortunately only in Dutch. I am really very curious how the narratives are contructed in this movie.

@Mike Ellwood,

“The Observer is, in effect, the Sunday Guardian”

Only worse!

I’ve been arguing that the forecasts were rubbish for the last 2 years. When diaaster didn’t immediately strike, hard-line Remainers immediately started saying “wait till article 50 is triggered”.

Then of course it was triggered and the twitter crowd I debate with was replaced overnight by people saying ” but we haven’t left yet!”. (Even as the various institutions started to publish sheepish retractions, saying “the economy seems to be doing rather better than we expected…”

One comedic feature is when they say that only emergency intervention by the treasury & bank of England saved s from recession – in which case one wonders why the possibility of such measures weren’t included in the forecast models… I don’t know how to get this into people’s heads: it means the forecasts were based on false assumptions, and therefore untrustworthy!

Any bad economic news over the next 20 years will be blamed on Brexit by the whinge-mob who can’t accept a referendum result and want to overturn it, no matter what. The truth is that most voters could hardly fail to hear & be influenced by Project Fear – but rightly distrusted it, and saw the importance of the sovereignty issue.

“Any bad economic news over the next 20 years will be blamed on Brexit by the whinge-mob who can’t accept a referendum result and want to overturn it, no matter what. The truth is that most voters could hardly fail to hear & be influenced by Project Fear – but rightly distrusted it, and saw the importance of the sovereignty issue.”

The EU has been taking credit for everything good that’s happened to the UK economy since 1973.

The “sick man of Europe” really runs deep.

Hello,

I calculated the sectoral flows for the UK the other day and the private sector balance was about -6% of GDP!

Private credit creation was about 2.5% which means the balance was met with the selling down of private financial assets.

This is because of the negative external balance and the natgov surplus budget, the coming crash will be falsely blamed on Brexit and perhaps used to further undo Brexit.

Though I think that austerity and co were on the menu with or without Brexit.

One can join the dots on how this will go politically.