I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

No cause for celebration

I wrote the following piece this morning for tomorrow’s local Fairfax newspaper. While some of the content is definitely of local interest there might be some things of interest to the broader debate. Also it is written to fit a column so it doesn’t allow for much elaboration.

Economics has become an agricultural pursuit in recent months as we all search for those “green shoots” of recovery. Overall Australia has experienced an attenuated downturn compared to the economic devastation abroad.

We avoided the dreaded two consecutive quarters of negative growth which define a formal recession although the ABS data shows that our economy has contracted slightly over the last six months. So one average we are in a GDP-recession.

However, compared to sharp and prolonged 1991 recession, the current episode is, so far, rather muted. Retail sales continue to grow (up 6 per cent). Our export volumes have risen by around 2 per cent. The share market is recovering (20 per cent since March) and profits are returning. Business and consumer confidence is rising.

Australia is running against global trends. The very early and substantial federal stimulus packages have definitely put a floor into the downturn and helped private sector confidence to return.

Nonetheless, there are several disturbing trends. The banks, under the protection of government guarantees, have driven smaller non-bank lenders out of the market and refused to pass on lower rates. The mortgage and credit card markets are now less competitive.

If we can scrape a recession out of the natinoal accounts data, then the deterioration in the labour market surely defines this episode as a recession. Total employment growth is near zero. Full-time jobs have fallen significantly, reflecting the absolute decline of manufacturing but have been more than offset, so far, by part-time job creation. As a result, males have endured the major brunt of the downturn to date given they have a higher share of manufacturing and construction employment and females are concentrated in the sectors that have benefitted the most from the spending stimulus.

Firms are shedding hours of work faster than persons so underemployment is rising faster than unemployment. The national unemployment rate has risen sharply (by 1.9 per cent) to 5.8 per cent and underemployment has also accelerated and is now around 8 per cent.

Taken together, the total labour underutilisation rate is around 13.8 per cent which constitutes a huge waste of labour potential.

Given the flat GDP growth forecasts, notwithstanding a return to growth, unemployment will continue rising over the next year or more which means that high levels of long-term unemployment will become entrenched.

While the stimulus packages have provided some boost to spending and allowed private saving to rise without a major recession occurring, they have categorically failed to target the unemployment loss and direct job creation is required to stop the labour market malaise from worsening.

Most of the benefits from the stimulus packages around the world appear to be aiding the top-end of town rather than the most disadvantaged workers and low-income consumers. At the end of this episode we will see large pools of long-term unemployment; flat wages growth; real wage cuts for minimum wage workers; increased precariousness of work – but a return to record bank profits and financial sector largesse.

Only a major job creation strategy which can support the growth in the labour force and also provide a sponge to the huge pools of underutilised labour will be able to provide some equity in the expansion phase. It is an urgent and missing component of Federal Government macroeconomic policy.

Job creation policies are definitely required in the Hunter and Newcastle areas.

In our local region – the Hunter and Newcastle areas, regular commentators from the business lobby – who continually are talking up the economy for their own benefit – point to our relatively low unemployment rate (currently 6.1 per cent) compared to NSW as a sign that our economy is holding up better than most. They even compare it to the other steel city, Wollongong (south of Sydney) which has suffered rising unemployment rates (currently around 9 per cent).

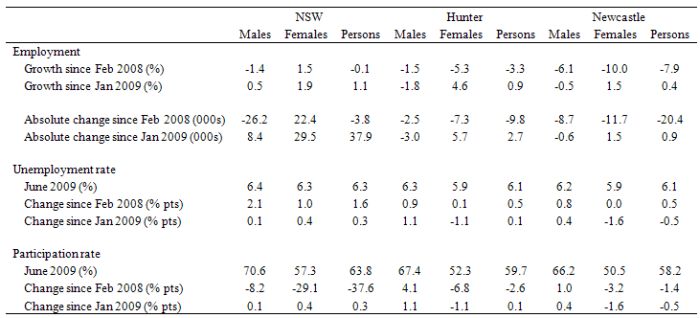

Since the downturn began in February 2008 (that was the month of the low-unemployment rate in the last growth cycle), the unemployment rate in the local area has risen only 0.5 percentage points which looks good compared to NSW (1.6 percentage point rise). Further, the Hunter/Newcastle unemployment rate has fallen since January as the stimulus package impacts positively (see the Table which summarises the broad labour market trends).

But relying on a single indicator is dangerous. Especially one that is constructed using a ratio where both the numerator and the denominator are sensitive in different ways to the state of the economic cycle.

Local employment growth is relatively poor. Since February 2008, Hunter employment has contracted by 3.3 per cent (10 thousand jobs) while Newcastle has lost a staggering 7.9 per cent (20 thousand jobs). NSW employment contracted by only 0.1 per cent (4 thousand jobs). Even this year, as fiscal policy has been supporting spending, our region has performed relatively poorly.

An additional perspective is that, nationally (and for NSW), females have fared better than males in the downturn. However, Hunter and Newcastle females have suffered greater job losses than males.

So why is our unemployment rate comparable to the NSW average and also the National average yet out employment losses have been significantly larger? The answer lies in the labour force participation rate which is the percentage of the working age population that is employed or desires work and is actively looking for it.

There are two offsetting tendencies operating in a downturn: (a) the “added worker” effect where families try to protect total incomes by increasing the participation of the “second-breadwinner”, typically the female; (b) the “discouraged worker” effect where people giving up searching for work as vacancies collapse. The net participation rate change in any month depends on the strength of each of these effects. Typically, the added worker effect dominates early in a recession but is later swamped by discouraged workers leaving the labour force and so eventually participation falls.

Remember, the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed divided by the labour force. Both parts of the ratio move during a downturn. So if the employment losses are translating into a shrinking labour force rather than rising unemployment then the unemployment rate may actually fall or stay unchanged despite a meltdown in jobs.

Since February 2008, NSW participation rates have risen (same for Australia) which is a common aspect of the early stages of the downturn. The added worker effect is dominant especially as part-time work is growing. However, participation rates in the Hunter region have fallen by a substantial 2.6 percentage points and for the city of Newcastle by 1.3 percentage points over the same period.

So our unemployment rate is being “artificially” held down by the workers leaving the labour force. This “hidden unemployment” disguises the extent of the deterioration in the local labour market.

How might we measure this effect? What would be the situation if the local region enjoyed the higher state average participation rates.

If we currently enjoyed the higher NSW average participation rates (which were close to the local regional rates at the outset of the downturn in February 2008) and the local employment levels were unchanged from their current situation, then the Hunter unemployment rate would be 12.1 per cent and the Newcastle rate would be 14.4 per cent.

That should change one’s perspective of how the local region is faring.

While the truth lies somewhere between the official data and these projections (employment would probably be higher if participation rates were higher) there is no cause for celebration.

Local politicians and those of influence should be lobbying the Federal Government daily to introduce large-scale direct job creation programs. Standing by and watching the labour market deteriorate in this way is the anathema of leadership.

This Post Has 0 Comments