In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Foreign sales of US government debt are largely irrelevant

Happy New Year to all readers. I will not write much today (to reflect to on-going holiday spirit!). But, there was an article in Bloomberg media (December 30, 2016) – Beware the Foreign Exodus From Treasuries – stirring up fear about the recent sales of foreign-held US government debt. I guess it was a slow news day or something because there is very little in the story that is relevant to assessing whether the US government can run an appropriate fiscal policy stance. The fact is that the foreign sales of US government debt are largely irrelevant for the US government’s capacity to maintain its net spending program. The sales are in US dollars and only the US government itself issues those dollars. To think that a foreign purchaser of a US Treasury debt liability are ‘providing dollars’ to the US government is to completely misunderstand the nature of the transaction. This blog considers the current data and explains how to think correctly about these matters. The question that financial commentators really should be asking is why should the US government extend that corporate welfare (risk-free bonds with income flow) to domestic bond-buyers and foreign governments/private investors. There is no financial reason (in terms of facilitating fiscal policy) for the bond issuance. It is just a form of welfare spending which helps the top-end-of-town.

The gist of the Bloomberg article is as follows:

1. “The biggest foreign buyers of U.S. government bonds are quickly retreating after years of absorbing record amounts of the securities”.

2. “This is an important dynamic to understand when looking at the potential fate of the $13.6 trillion Treasury market in 2017.”

3. “It’s hard to see how these bonds can significantly rally, even in the face of bad news, given the exodus of foreign central banks from the U.S. government-debt market”.

4. “it’s not just the big governments that are selling. Private foreign investors have been net sellers recently, too”.

5. “This foreign withdrawal will most likely continue for the foreseeable future”.

6. “there’s a solid argument to be made that the latest selloff has gone too far and will correct soon enough”.

7. “But this backdrop of foreign selling is important. Yields on 10-year Treasuries may not quickly shoot up, but they most likely won’t plunge back to the lows of 1.36 percent seen in July.”

The point to understand is that while the trends described in the article are actually happening the importance of those trends is close to zero when assessing the capacity of the US government to run its fiscal policy program, which, might include a large increase in public infrastructure spending under the new administration.

As we see below, the foreign purchases of US government cannot be construed as funding the US government. If that government chooses it can keep spending with zero foreign government debt purchases.

The story came out a few days after the US Department of the Treasury released its latest – Treasury Bulletin (December 2016). You can always get the most recent issue of the Bulletin HERE.

Here is an update on some research I did in this regard a few years ago which appeared in these blogs:

1. The nearly infinite capacity of the US government to spend.

2. When the government owes itself $US1.6 trillion.

3. The US government can buy as much of its own debt as it chooses.

4. Helicopter money is a fiscal operation and is not inherently inflationary.

There are a few data sets that you can pull together to break the total US public debt outstanding down into various categories:

- The US Treasury’s Bulletin Chapter on Ownership of Federal Securities, which provides a detailed breakdown of who holds the outstanding US government debt.

- US Treasury Foreign breakdown.

- US Federal Reserve Bank’s Consolidated Balance Sheet data.

- US Federak Reserve Bank’s Financial Accounts of the United States.

So what has been going on?

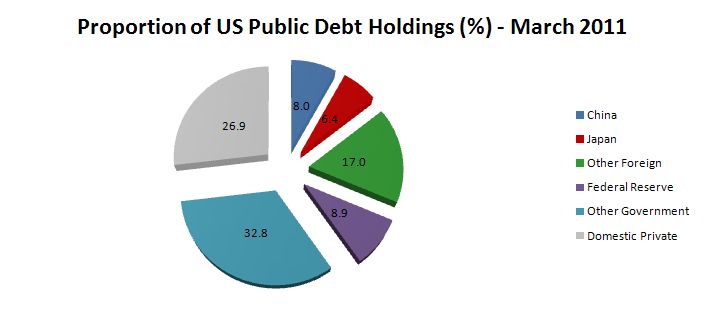

First, 2011.

The following pie-chart shows the proportions of total US Public Debt held by various categories as at the March-quarter 2011.

The government sector held about 42 per cent of its own debt. These holdings were either in the intergovernmental agencies or the US Federal Reserve Bank.

The US Federal Reserve held 8.9 per cent of total US public debt. Its total holdings were around $US 1,274.3 billion.

The three largest foreign US debt holders at the March-quarter 2011 were China (8 per cent), Japan (6.4 per cent) and Britain (2.3 per cent). The total foreign held share was equal to 31.4 per cent.

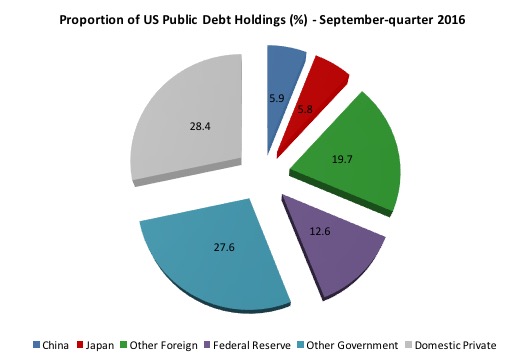

Now, to the most recent data – September-quarter 2016.

As at the end of September 2016, there were $US19,597.4 billion Federal Securities outstanding. These were broken down into:

1. Privately held – $US11,709.9 billion (59.8 per cent of total).

2. Federal Reserve and Intragovernmental holdings (SOMA and Intragovernmental Holdings) – $US7,863.5 billion (40.2 per cent of total).

3. Foreign and international – $US6,154.9 billion (31.4 per cent of total) – of which $US3,901.7 billion held by Foreign Official institutions.

A comparison of movements over the last 5 or so years in the composition of US Treasury debt holdings is provided by the following two pie charts

The following pie-chart shows the proportions of total US Public Debt held by various categories as at the September-quarter 2016.

The government sector held about 40.4 per cent of its own debt in the September-quarter 2016. This is slightly down on the proportions held in the March-quarter 2011.

These holdings were either in the intergovernmental agencies (27.6 per cent) or the US Federal Reserve Bank (12.6 per cent). So the central bank has increased its holdings over the period in question and now holds $US2,463.5 billion and increase of 93.4 per cent in overall levels.

The Chinese holdings were around 5.9 per cent of the total and hardly consistent with the rhetoric that China was bailing the US government out of bankruptcy. These holdings have fallen in recent years (see below).

The three largest foreign US debt holders at the September-quarter 2016, were China (5.9 per cent); Japan (5.8 per cent) and Ireland (1.4 per cent). The total foreign held share was equal to 31.4 per cent.

The impact of the British austerity is noticeable. In 2011, Britain was the third largest holder of US public debt (at 2.3 per cent of total US public debt). By March 2013, this had dropped to 0.95 per cent. They shed $US166 billion worth of US treasury securities in that 24 month period. As at the September-quarter 2016, the British share had consolidated at 1.1 per cent of the total.

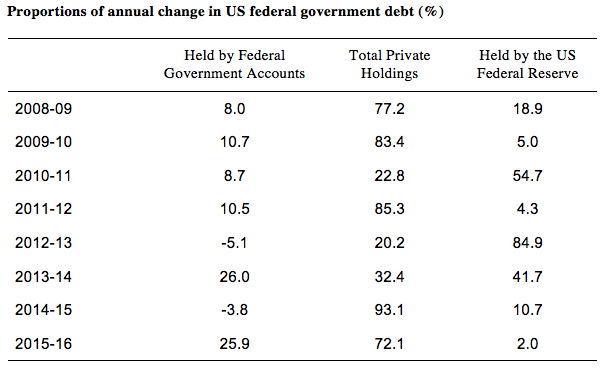

The following Table shows the proportions of the total change in US federal government debt for the calendar years 2009 (so the change is between 2008-09 and so on) to 2015-16 (up to September 2016) accounted for by the main holders – Federal Government Accounts, Total non-government (private), which is, in turn, decomposed further into US Federal Reserve holdings. There are other components not included.

In 2011, the increases in the US Federal Reserve’s holdings accounted for 54.7 per cent of the total increase in US federal government debt. That fell away to 4.3 per cent in 2012 and then rose again to 84.9 per cent in 2013.

The proportion has been decreasing since then and in 2016, the proportion was only 2 per cent as the US Federal Reserve ended its asset-buying programs.

The recent history thus provides a very important lesson. The US central bank can initiate very dramatic shifts in the mix of debt holders whenever it chooses.

This means that the central bank can always purchase any debt that the private sector chooses not to purchase via the primary auctions.

There is never a reason for US government bond yields to rise above a level that the government considers to be acceptable.

To repeat, the US government (consolidated Treasury and central bank) can always assume the role of its own largest lender and borrow as much as it likes from itself (subject to Congressional ceilings etc).

That is how nonsensical these voluntary conventions are. They sound robust but in the end the currency-issuer is the currency-issuer and can always work around the so-called constraints.

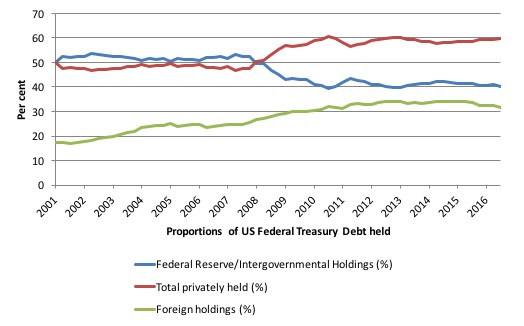

The next graph shows the evolution from March 2001 to September 2016 of the US public debt by private, public and foreign holdings (%). The foreign holdings are a subset of the private series.

There are some interesting points to note. At a time when the US public debt ratio has risen beyond what the mainstream claim is the danger point (80 per cent) – the point after which we are repeatedly told a nation will struggle to ‘fund’ its outstanding public debt – the private demand for US public debt has risen.

Private markets know that US Treasury debt is risk free, despite all the scare mongering that the likes of the Peter Peterson Foundation and its ilk might regularly entertain.

The other point, in relation to the rising foreign share is that you cannot conclude that the foreigners (China, Japan etc) are ‘funding’ the US government. The US government is the only government that issues US currency so it is impossible for the Chinese to ‘fund’ US government spending.

To understand the trend shown in the graph more fully we need to appreciate that the rising proportion of foreign-held US public debt is a direct result of the trade patterns between the countries involved (and cross trade positions).

For example, China will automatically accumulate US-dollar denominated claims as a result of it running a current account surplus against the US. These claims are held within the US banking system somewhere and can manifest as US-dollar deposits or interest-bearing bonds. The difference is really immaterial to US government spending and in an accounting sense just involves adjustments in the banking system.

The accumulation of these US-dollar denominated assets is the ‘reward’ that the Chinese (or other foreigners) get for shipping real goods and services to the US (principally) in exchange for less real goods and services from the US. Given real living standards are based on access to real goods and services, you can work out who is on top (from a macroeconomic perspective).

Note that a worker in Detroit or some other degenerate industrial region in the US who is suffering from unemployment as a result of cheaper imports coming from nations with lower labour standards (pay and conditions) than the US is unlikely to agree with me. In his/her case I wouldn’t agree with me either.

But from the perspective of macroeconomics there is no issue.

The point is that the US Federal Reserve Bank (as in the case of other central banks around the world) have been taking up significant proportions of the outstanding government debt in the last 10 years. In some years, this proportion has been very high.

We didn’t observe any major inflationary spikes associated with these shifts in monetary operations underpinning the government debt-issuance (and deficit) outcomes.

Please read my blog – Direct central bank purchases of government debt – for more discussion on this point.

Also please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Here are some other observations that impact on how one interprets the Bloomberg article.

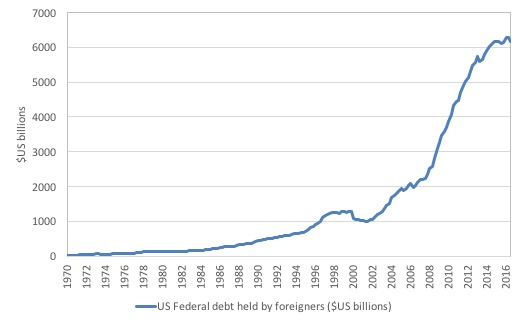

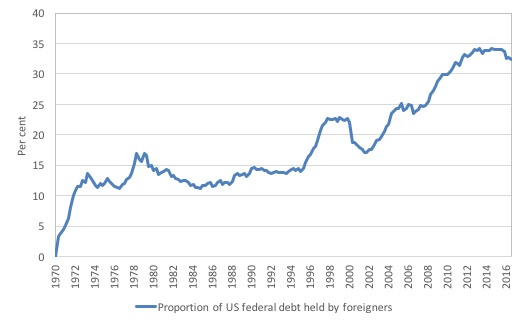

The following graph shows the total US Federal debt held by foreigners since 1970 (in $US billions). There was a dramatic escalation after 2000.

The same data expressed as a proportion of total US Federal debt is shown in the next graph since 1970. You can see that the downturn since 2015 has not been very dramatic in historical times. The US has witnessed variable shares of total debt held by foreigners over this long historical period.

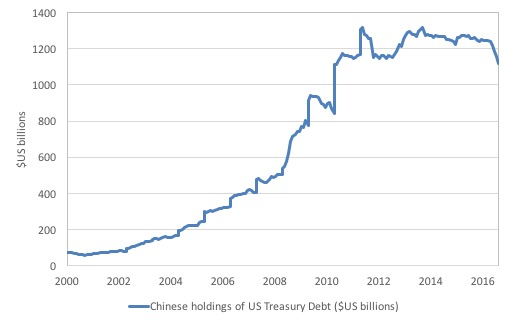

The next two graphs provide some insights into how scale affects our assessment of graphical evidence.

The following graph comes from the Bloomberg article (under the heading Fire Sale) and shows the holdings of US Treasury debt (in US billions) since July 2010 up to October 2016.

The vertical scale chosen gives the ‘falling over the cliff’ impression.

The next graph shows the same data (in $US billions) from March 2000 to October 2016 without any adjustment to the vertical scale (other than it is linear).

These Chinese sell-offs have occurred in the past – and no-one really blinked an eyelid.

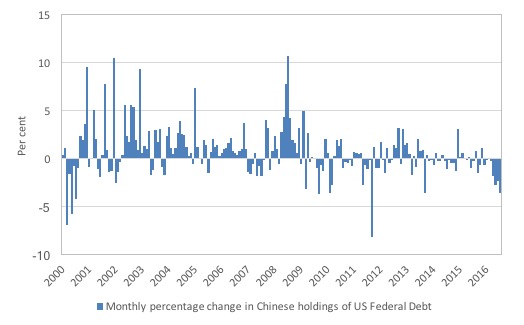

The next graph shows the monthly percentage change in Chinese holdings of US Federal Debt from March 2000 to October 2016. I adjusted the data to exclude the impacts of the series breaks which have occurred in the month of June (in several of the years shown).

Historically, the time series has been quite volatile and the current monthly reductions do no seem out of the ordinary.

Conclusion

As a proponent of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), I do not consider there to be a public debt problem in the US so the analysis presented here is out of interest rather than establishing anything substantive.

However, what it shows is that even within the voluntarily-constrained system that regulates the relationship between the US treasury and the central bank, the latter can still effectively buy as much US government debt as it likes.

So if yields rise on US Treasury debt in the coming year it will be because the US government has chosen to allow higher interest payments on the corporate welfare it extends the non-government sector in the form of voluntary debt-issuance.

The question that financial commentators really should be asking is why should the US government extend that corporate welfare to domestic bond-buyers and foreign governments/private investors.

There is no financial reason (in terms of facilitating fiscal policy) for the bond issuance. It is just a form of welfare spending which helps the top-end-of-town.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Just one question. Is debt the relevant word?

Has Louisa Connors suggested a better word or words yet?

Bill is right to question the purpose of government debt. Milton Friedman advocated a “zero debt” regime, and Warren Mosler likewise. For Friedman, see his para starting “Under the proposal…” here:

http://0055d26.netsolhost.com/friedman/pdfs/aea/AEA-AER.06.01.1948.pdf

For Mosler, see for example his 2nd last para here:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/warren-mosler/proposals-for-the-banking_b_432105.html and here:

http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp-pdf/WP37-MoslerForstater.pdf

Also, government borrowing (unless there is a very good reason for it) artificially raises interest rates (which I don’t think Bill mentioned). Typically, governments borrow so as to ingratiate themselves with voters (i.e. buy votes) as pointed out by David Hume 250 years ago. I.e. if a government net spends too much into the economy and has to rein in demand by borrowing so as to deal with that, that will artificially inflate interest rates.

Ralph Musgrave, Bill has been pretty clear that government borrowing as practiced does nothing to rein in demand in the economy. And that a currency issuing government’s “borrowing” does not have to inflate interest rates.

I get the point about there being no need for a sovereign currency issuer to issue debt with a zero interest rate policy -but:

The day to day banking system relies on the to and fro of bonds to maintain reserve levels -if it doesn’t have those bonds how will it achive this?

I’m probably missing something here, but any help with this issue appreciated.

Dear Simon Cohen (at 2017/01/02 at 8:45 pm)

The capacity of a currency-issuing government to spend without issuing debt has nothing to do with interest rate policy. The central bank could target any interest rate it desired without the need to conduct open market operations (exchanging debt for reserves) by simply paying interest on excess reserves.

best wishes

bill

“The day to day banking system relies on the to and fro of bonds to maintain reserve levels -if it doesn’t have those bonds how will it achive this?”

It doesn’t.

Reserves are operationally irrelevant to the day to day business of banking. They are a complete red herring. The private banking system has no need of reserves *at all* to function.

Always remember that at the end of clearing the central bank is entirely out of the game. All the private banks end up lending to each other to balance their private lending assets. The central bank system is just a convenient way of getting to that position that requires less active collateral than doing it peer-to-peer.

I had the same question as William. I’ve found myself using “debt” instead of debt and coupons instead of interest.

Thanks Bill and Neil for your responses. One thing still confuses me:

I thought that banks use repos (bonds that have repurchase date?) in cases where the real time gross settlement leaves them short of reserves so the selling of the bonds fills the gap? I mean if the reserves fall short and someone cashes a cheque from that bank – then there’s an issue?

Am I still missing something?

William, Alphonso,

You can use the term ‘total government bond issuance’ instead, perhaps.

Kind Regards

Neil

If there were no reserves how would banks settle up ?

Surely they would have to start carting gold to eachother’s head office.

Adding to Neil Wilson’s comment re no need for reserves:

The Canadian banking system, arguably the most secure in the world, does not use reserves. In the Canadian banking system “reserves“ are called “settlement balances“, a term which describes their actual function, i.e. they are the balances of the various banks in the inter-bank system. At the end of each day they net to zero once all bank transactions have cleared and settled.

During the worst of the financial crisis the Bank of Canada did maintain a slightly positive balance of settlement balances ($25 million?) in the inter-bank system to ensure the overnight interest rate remained at zero.

Bill describes monetary operations somewhere in his blogs. I’m afraid I don’t remember where for those who would like to follow up.

“I thought that banks use repos (bonds that have repurchase date?)”

Not usually. If one bank is up in the central bank account and another bank is down in their central bank account then the one that is up lends to the one that is down at a rate a little higher than what they would get if they left it on deposit at the central bank.

That’s how the central bank maintains a ‘base rate’. A bank that is short at the end of the day has to outbid the central bank deposit rate, and a bank that is up has to lend at less than the ‘penalty rate’ the central bank will lend to a bank at. The result is an inter bank rate that sits in a strict corridor.

“If there were no reserves how would banks settle up ?”

It’s automatic as a function of the payment system. Like this.

If a customer has an account at your bank then a payment is a simple internal journal

DR payer Y account, CR payee X account.

If it is between banks then you just mark up the target bank’s client account at your bank.

DR payer Y account, CR Bank B client account (ref: payee X).

Bank B then ‘lends’ to bank A automatically. Like this:

DR client account with Bank A, CR payee X.

Thanks Neil,

So it seems there is no real need for bonds to keep the banking system balanced as the aggregate will always net out.

As a matter of interest is it a corridor system or a ‘floor’ system in the UK at present? Bill has written about 0% being the ‘natural’ rate -does this mean 0% is the floor (i.e target rate same as base rate? Can only partially get my head around this stuff.

Bill mentions ‘The capacity of a currency-issuing government to spend without issuing debt’.

In this context:

1. Government debt held by Federal Government Accounts and Federal Reserve is not debt?

2. How is it correlated with the value of that currency?

The UK runs a ‘floor’ system in that deposits get paid the base rate, which is supposed to stop the interbank dropping below that value.

It doesn’t though. The Interbank sits slightly below the bank rate for reasons the Bank of England make that are less than convincing.

There is no financial reason (in terms of facilitating fiscal policy) for the bond issuance. It is just a form of welfare spending which helps the top-end-of-town…. Prof. Bill Mitchell

Or deficits could be financed with negative to 0% yeilding sovereign debt – to maintain the central bank’s ability to sop up reserves if deemed desirable. But who will buy negative to 0% yeilding sovereign debt? ans: Those who would otherwise have to pay even more negative interest on fiat account balances at the Fed.

But what about the non-rich? Should they pay negative interest too? ans: No, since SOME risk-free liquidity/savings is legitimate so an individual citizen exemption of up to, say, $250,000 US should accompany negative interest on reserves (NIOR).

But won’t the banks try to pass on negative rates to non-rich depositors? Yes, but who needs banks anyway since all citizens should be allowed inherently risk-free accounts at the central bank itself?

But what about the strength of the US dollar if it can no longer buy welfare proportional to wealth? ans: It’ll probably go down but that should increase US exports and increase jobs.

Andrew Anderson,

Bill is talking about government running a deficit without any bond issuance at all.

Normally, the government spends first and then either,

a) taxes some of the money back or,

b) ‘borrows’ it back through issuing government bonds, which just replaces ordinary money with bonds.

Issuing bonds (b) is not necessary, as Bill says above.

It is best to imagine that the government spends first, before taxing or borrowing it back.

Kind Regards

Neil Wilson,

My understanding is that the BoE now has a support rate (or deposit rate) which sits slightly below the bank rate. I can’t remember what it is and I could be wrong, but I thought they introduced it after the GFC.

Simon Cohen,

Many central banks refer to their support rate as a ‘deposit rate’, i.e. the rate of interest banks get for keeping reserves deposited at the central bank. The Penalty rate (again the name might vary) sits at the top of the corridor, and the bank rate (target short term interest rate) sits dead centre.

If there are excess reserves in the banking system overall, the actual inter-bank rate falls to the support rate. Meaning the inter-bank rate falls below the target. QE causes excess reserves, as does not issuing debt to match the deficit.

MMT advocates that the Target Short-term Interest Rate and Support Rate should be the same. This means the central bank can always hit its target short term interest rate no matter that there are excess reserves in the banking system, because the support rate IS ALSO the target short term interest rate.

Kind Regards

Instead of the word debt, could we call it a “Government Holding” similar to commercial banks having safety deposit boxes for customers?

Simon Cohen,

… and further to the above, the Penalty Rate should also be the same as the support rate and bank rate, so no corridor under MMT. And that single rate should normally be low or zero.

If the central bank wants to influence the provision of credit, it should do so by properly regulating banks so they don’t lend to people who cannot pay it back. I personally think that adjusting minimum capital limits to cover potential losses can also help.

Kind Regards

Issuing bonds (b) is not necessary, as Bill says above.

True, but I’ve pointed out we could issue NEGATIVE yeilding sovereign debt. That’s even better than not issuing bonds since who could complain about a National Debt that earns interest for the monetary sovereign?

And why shouldn’t there be negative interest on large account balances at the central bank?

Please re-read my comment. I fear you’ve missed some subtle points.

Andrew,

Fair enough, I wasn’t sure what you were getting at.

As for what you said, I will look into it.

Kind Regards

hey neil,

what are the reasons the boe gives for paying a support rate slightly below the target.

think most central banks adopt this practice,

in my work, im always looking at yields and volume calculations, and we build in statistical error rates and risk management into where one would set the yield at as opposed to doing exactly what some forecast driven by the data would recommend.

curious to know anyones thoughts.

@neil wilson

“A bank that is short at the end of the day has to outbid the central bank deposit rate, and a bank that is up has to lend at less than the ‘penalty rate’ the central bank will lend to a bank at”

im curious , im wondering how often does this happen though. the central bank and the banks themselves have a buffer built into the system don’t they. doesn’t the central bank try and predict demand especailly because government related tranasactions can be very lumpy.

one bank might not know the other banks position im assuming , but the central bank is god and they can see the total market liquidity

doesn’t the fed for instance add the liquidity first pre any bond issuance so there is no problem clearing.

perhaps someone can enlighten me

mahiash,

“doesn’t the fed for instance add the liquidity first pre any bond issuance so there is no problem clearing.”

I’m no expert, but that is how I understand it.

The central bank may want to drain excess reserves by setting a target rate above the support rate, but in reality it is the Treasury that achieves that be issuing bonds to match the government’s deficit.

With a single rate, which is equal to the support rate, the target rate and the penalty rate, no bond issuance is necessary.

Jerry Brown, You claim “Bill has been pretty clear that government borrowing as practiced does nothing to rein in demand…”.

That depends on what you mean by government borrowing. What I mean is “government borrowing, period, full stop”. I.e. I’m referring to where government simply borrows $X, sits on that money and does nothing more. And as to interest rates, if they drift upwards as a result of that extra borrowing, government ignores that. That is clearly deflationary.

In contrast, what Bill is referring to I assume is “government borrows $X and spends it”. That’s a different kettle of fish. I.e. in that case there is a large stimulatory effect from the spending. As to the NET stimulatory effect, I’d guess there is one, but I’m never quite sure. And as to interest rates, if government kept those constant despite the extra borrowing, that would tend to boost any stimulatory effect.

Ralph Musgrave @17:37,

Perhaps you are right that if a government borrowed its own currency from the private sector and just sat on it and wasn’t doing that borrowing so as to “cover” any expenditures and it also prevented the central bank of the government from purchasing those bonds or for allowing them to be used as collateral for loans then that could be contractionary for the term of the bond. If the private sector actually had the intention of spending that money in the first place. I had not considered that scenario. And you are right that I should not have made claims as to what Bill Mitchell would say about that.

On the other hand, that is not how “government borrowing as practiced” has been practiced to my knowledge. But governments often do stupid things, and I guess they could do something like this as well.

Mahaish,

‘because government related tranasactions can be very lumpy.’

As I understand it, the ‘lumpiness’ in the reserves is dealt with by the Treasury (UK) having accounts with banks so that, for example, Tax money stays in the system so that the reserve levels are not disrupted too much -the US has a similar approach.

Great essay on this by Stephanie Kelton: http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/can-taxes-and-bonds-finance-government-spending

Re Neil Wilson, Tuesday, January 3, 2017 at 3:49 and Mahaish, Tuesday, January 3, 2017 at 8:48.

Re the interbank rate being lower than the central bank floor rate:

I put this question to a deputy governor of the Bank of Canada half a dozen years ago. His answer, delivered after a week, was that not all financial institutions trading in the interbank market have access to the Bank of Canada floor rate. These financial institutions bid the interbank rate slightly lower than the floor rate in order to get rid of their excess balances.

Regarding the term “government debt”, I think that “national savings” is the correct term.

The government sector is acting as a bank, with short term reserve deposits and long treasury deposits. No one seriously thinks of unsecured bank deposits as bank “debt”, neither should we give unsecured government deposits the weighty term government “debt”. These are totally differently beasts to secured borrowings.

Regarding the effect of bond issuance on demand, I think the above terminology clears it up nicely. Moving from short term to long term government deposits has very little effect on your ability to spend. This is pretty much all embodied in the banking system. Bond transactions just shuffle around the banking deposits and change the wealth welfare budget.

@ keith newman,

interesting , so its to guarantee clearing.

pretty much the same strategy I use, set the yield slightly below the recommendation to guarantee clearing, in the absence of overwhelming market demand.

the question is , what kind of sensitivity analysis they use to determine the gap between the floor and the target. do they have set rules , or is it just convention.

Brendann, I’m in agreement. We could turn the language against the neo-libs if we can get ‘private sector’ or even ‘non-government’ when talking about deficits and bond issuance.