The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

France Stratégie’s three options for the Eurozone ignore the elephant

I read a short discussion paper this morning – What model for the future of the eurozone? Critical actions – released by France Stratégie, which is formally known as the Commissariat général à la stratégie et à la prospective (CGSP). It is a government body attached to the Prime Minister’s office. It was created in April 2013 Its mission is to provide broad discussion parameters to aid future policy directions for the French government. The discussion paper provides nothing new and seems to avoid the realities of the European cultural and historical milieu that really dominates or constrains (whichever way you want to think about it) the possible routes back to prosperity for the continent. It lists three options for reforming the Eurozone: (a) Return to original principles (Maastricht 2.0) where nations were fiscally separate and there would be no bailouts; (b) Reinforced fiscal integration with “joint liability for sovereign debt” and control of “national parliaments’ fiscal sovereignty’ by some European-level institution (Commission/Parliament); and a (c) a US federal model. They are motivated by the conclusion that the current situation is “ineffective”, which is a euphemism for total dead-in-the-water failure. They do not broach the most obvious and, in the long-run, best solution, which is consistent with the cultural and historical realities – orderly breakup and return to true currency sovereignty. So the discussion paper really offers very little by way of a path out of the maresme that the elites in Europe have created to line their own pockets at the expense of everyone else.

Interestingly, France Stratégie superseded the Centre d’analyse stratégique (Strategic Analysis Centre), which, in turn had replaced the old Commissariat général du Plan (Planning Commission) set up in 1946 by Charles De Gaulle under the stewardship of Jean Monnet.

The Planning Commission was a large body and very Keynesian in nature. It issued five-year plans and dominated policy making in France until the 1980s, whereupon the Finance Ministry, by then crawling with Monetarists, became more influential and allowed Jacques Delors to push through the Maastricht negotiations, against the better interest of France.

The Planning Commission would never have recommended the creation of the monetary union along the Maastricht lines. It understood the power of currency-issuance and the role that the state has to play in allowing its fiscal parameters to offset the fluctuations in the non-government spending cycle.

Monnet’s original work in the Planning Commission was characterised by his 1945 Plan (Theory of l’Engrenage), which was characterised by pursuing a series of small innovations that would ultimately establish the institutional machinery to accomplish broader political integration in Europe.

It should never be forgotten that Monnet was motivated by a desire to render Germany powerless to ever mount a martial campaign with European borders.

The first small step he proposed was the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community, which was aimed at taking over German coal-production and diverting output to French industry. The aim was to reduce the power of Germany and advance French capacity.

While aimed squarely at keeping Germany subservient to France, Monnet also considered these steps would necessitate some intergovernmental cooperation between France and Germany. These small innovations would ultimately, he thought, lead to the creation of the European Common Market.

But the French aimed to dominate the new European body. They only wanted ‘Europe’ if it pacified and weakened Germany and elevated France to the top of the European pecking order.

What Monnet didn’t anticipate was that the neo-liberal ideology (Monetarism and more) would come to dominate and usurp the state’s fiscal capacity, turning it into a destructive force, where pro-cyclical macroeconomic policy changes were considered responsible.

Monnet’s incremental plan towards European integration turned into a monster. And if France thought it would run the show at the European level it was sorely mistaken.

The writing was on the wall in the 1970s when the various fixed exchange rate regimes that the Europeans created after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971 really became Mark-zone. Germany was dominant economically and treated its European partners with contempt.

I discuss all that in detail in my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (which, by the way, is now available in cheaper paper back format).

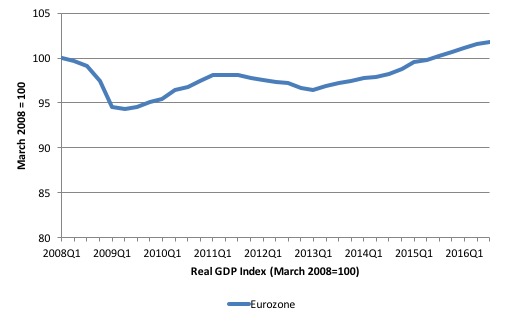

The following graph sums up the Eurozone failure. It shows real GDP indexed to 100 in the March-quarter 2008 and graphed to the September-quarter 2016.

By posting this graph I am not suggesting that economic growth per se is the desirable end. I could have posted any number of indicators that fall out of this growth performance (such as the unemployment rate, wages growth, inequality indexes etc).

They all tell the same story – failure of a monetary system to deliver prosperity.

Since the March-quarter 2008, the overall 19 Member States of the monetary union have grown by 1.8 per cent – 8.5 years for 1.8 per cent – that’s a massive failure.

Then, if we disaggregate, we find only 10 of the 19 Member States have grown past the March-quarter 2008 peak. Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia and Finland are still recording economic activity below the pre-GFC peak level.

The Greek economy has contracted by 26.3 per cent in real terms since the March-quarter 2008, Italy by 7.6 per cent, Finland by 5.1 per cent.

The monetary union was meant to create convergence but has, in fact, generated wider disparities in economic fortunes. By surrendering their currency sovereignty these Member States are now worse off than they were in March 2008.

And most of the Member States who have finally reached production levels above the pre-GFC peak are only just above.

One word is apposite – failure. We could be less parsimonious – catastrophic failure.

France Stratégie recognises this failure by saying:

While the euro area has undertaken reforms since 2010 that have allowed it to avert a breakup, its current institutional makeup lacks coherence. Member states are going to have to rethink the Maastricht compro- mise if they are to set this predicament right.

The reality is that it is only the actions of the ECB that have kept the Eurozone together. Had not it intervened in May 2010 with the Securities Market Program (SMP) several of the weaker nations, including Spain and Italy would have become insolvent and the monetary union would have collapsed.

The SMP involved the ECB buying government bonds in the secondary bond market in exchange for euros, which the ECB could create out of ‘thin air’. The SMP also permitted the ECB to buy private debt in both primary and secondary markets.

To understand this more fully, the decision meant that private bond investors (including private banks) could offload distressed state debt onto the ECB.

The action also meant that the ECB was able to control the yields on the debt because by pushing up the demand for the debt, its price rose and so the fixed interest rates attached to the debt fell as the face value increased. Competitive tenders then would ensure any further primary issues would be at the rate the ECB deemed appropriate (that is, low).

There was hostility at the time from the Germans. For example, the fiscally conservative boss of the Bundesbank at the time, Axel Weber, who was being touted to replace Jean-Claude Trichet as head of the ECB, was vehemently opposed. He resigned his post as an ECB Board Member.

Weber’s successor as head of the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann, maintained the criticism, albeit in a more muted manner.

Similarly, another ECB Executive Board member, Jürgen Stark, also resigned in protest over the SMP in November 2011. Stark told the Austrian daily Die Presse that the ECB was heading in the wrong direction by pushing aside the crucial no bailout clauses that provided the bedrock of the EMU.

He also said that the ECB had panicked by caving in to the pressure from outside of Europe.

Whatever spin one wants to put on the SMP, it was unambiguously a fiscal bailout package.

The SMP amounted to the central bank ensuring that troubled governments could continue to function (albeit under the strain of austerity) rather than collapse into insolvency.

Whether it breached Article 123 of the Treaty is moot but largely irrelevant.

The SMP reality was that the ECB was bailing out governments by buying their debt and eliminating the risk of insolvency. The SMP demonstrated that the ECB was caught in a bind.

It repeatedly claimed that it was not responsible for resolving the crisis but at the same time, it realised that as the currency issuer, it was the only EMU institution that had the capacity to provide resolution.

So while the ECB was put in that situation by the conduct of the Eurofin and European Commission in general, the fact remains that the SMP saved the Eurozone from breakup.

Without the SMP, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Greece and a bit later Italy, would have become bankrupt given the movements in the private bond markets at the time.

The reality is that the flawed design of the Eurozone, which reflected the ideological hold of neo-liberalism on the integration discussions in the 1980s and beyond, meant that the only effective fiscal capacity in the currency union was held by the ECB.

The Stability and Growth Pact constraints on fiscal policy and the bloody-minded approach adopted by the European Commission, particularly the Finance Ministers’ group (Eurofin), left the Member States impotent in the face of a major non-government spending collapse to defend their economies.

The flawed design of the Eurozone, which saw the Member States surrender their currency monopolies and adopt, what is in effect a foreign currency – the euro – meant that the Member States were dependent on the private bond markets for deficit funding.

When those bond markets demanded increasingly higher spreads on the German bund to fund the peripheral economies who were devastated by a decline in aggregate spending and production, the only way out was for the ECB to use its currency capacity to resolve the crisis.

The Eurozone would have broken up in 2010 had not the ECB worked around the Article 123 restrictions by buying massive volumes of struggling government debt in the secondary markets.

It was not so much a reflection of political pressure, which implies there were options. Rather, at that time ECB was the only option, given the flawed nature of the Eurozone architecture.

The other ‘reforms’ that France Stratégie mentions (such as the creation of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the tightening of the fiscal rules under the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and the decision to create a Banking Union in 2012, which is still an unfinished and deeply flawed conception) did not help save the Eurozone from collapse.

In fact, they have only made matters worse.

They have been touted as essential elements upon the path to closer integration by the European Commission but, in fact, make the original design flaws more damaging and unworkable.

France Stratégie also believes that these “incremental adjustments aimed at buttressing its institutional structure” have:

… taken the euro area further and further away from how it initially shared out different mandates. Monetary policy was to be entrusted to a single independent central bank, with the expectation that it would provide sufficient macroeconomic stabilization in the event of an economic shock affecting all member states equally (so-called “symmetric shocks”). In the event of an asym- metric shock, member states would be free to use their national budgets to provide stabilization on condition their deficits didn’t exceed 3% of GDP … It was up to the member states to ensure their deficits and public debt would not jeopardize their ability to respond in the event of a crisis. The no-bailout clause of the Maastricht Treaty, which prohibits joint liability on member states’ public debt – but was widely interpreted as precluding financial assistance for a state having difficulty accessing the bond markets – was supposed to help enforce market discipline and prevent countries from pursuing policies that would put them at the risk of insolvency.

Yes, all the above is true but:

1. The ECB’s one-size-fits-all interest rate policy helped spawn the huge property booms in Spain and Ireland, which came unstuck when the sub-prime crash came in the US.

2. The 3 per cent rule was too restrictive from the outset. This is a crucial point and the 3 per cent rule reflects the way that policy was generated in the lead up to the Maastricht Treaty.

Even before the Stability and Growth Pact was finalised, a few economists realised that the proposed fiscal rules would open the Member States to the problem of being forced by European Commission rules to introduce pro-cyclical fiscal policy interventions (raising taxes and/or cutting spending), the anathema of sound policy.

Discretionary fiscal policy changes should be ‘counter cyclical’ because the role of government is to ensure economic activity remains at levels consistent with full employment.

Government deficits should rise when output is falling and vice versa. The worst thing a government can do is to cut spending and/or increase taxes in an attempt to reduce its deficit as private spending falls off and the economy moves towards or into recession.

Austerity only makes the recession worse and further undermines the confidence of the private sector.

The GFC demonstrated the pro-cyclical bias in the Eurozone rules. As private sector spending collapsed, the deficits rose, not only because there were some attempts at discretionary stimulus, but also because the so-called automatic stabilisers were triggered as tax revenue fell and unemployment increased.

For many nations, this ‘cyclical’ impact was sufficient to breach the upper threshold of 3 per cent, which according to the nonsensical logic of the SGP, invoked the Excessive Deficit Procedure.

Pressure was then imposed on the nations to make discretionary cuts to their spending and/or raise taxes in an effort to offset the automatic stabilisers and maintain the overall fiscal balance below the 3 per cent threshold. That was madness.

As the recent experience has so emphatically demonstrated, imposing fiscal austerity on a nation in recession is self defeating because the attempts to cut the discretionary or ‘structural’ component of the deficit, further undermine the tax base and drive the automatic stabilisers into further deficit as economic growth deteriorates. An unemployed person pays no taxes!

The very fact that the automatic stabilisers were pushing the fiscal deficit up indicated that the government should have increased the ‘structural’ deficit to stimulate growth.

So the claims that there was sufficient flexibility within the 3 per cent threshold were demonstrated to be false. There is some fiscal flexibility (depending on the public debt situation) but clearly not sufficient room to defend a nation from serious recessionary forces.

The SGP has proven itself to be a source of neither stability nor growth.

3. The 3 per cent rule clearly does not allow a nation to defend its own banking sector.

4. Without the ECB decision to disregard the ‘no bailout clause’ there would be no Eurozone today (perhaps a Mark-Eurozone with a small number of nations as members).

The France Stratégie recognises that:

… a number of states today cannot shore up their economies because of the rules in place, which threatens their ability to handle a full-on crisis. The logic of the initial Maastricht setup, which intended to preserve the stabilization capacity of national budgets in the event of an asymmetric shock, is for all intents and purposes ineffective in several eurozone countries.

That is, the original design is unworkable and ad hoc adjustments to it are futile (“ineffective”).

So how can this “incoherent” situation be remedied?

France Stratégie believes that the Member States will “have to reexamine the Maastricht compromise and clarify the terms of the contract made between them if they are to build a more stable institutional base”.

They pose two broad questions to aid discussion:

– Are member states willing to abide by the common rules of fiscal discipline? If so, are they willing to take on a form of joint liability on their public debt? Or would they rather keep responsibility for public debt strictly national?

– Do member states want fiscal stabilization for the euro area as a whole? If so, do they want this to be centralized via a common budget? Or would they prefer it to be decentralized by coordinating national fiscal policies?

I can answer them now.

Question 1a: Probably not because the common rules are unworkable. Spain defied them in 2015 and saw that breach generated growth. The European Commission overlooked the breach because they wanted to shore up the electoral prospects of the PP (conservatives). Greece is currently attempting to defy the rules – again. It will be bulldozed!

Question 1b: Germany will never allow a “joint liability on their public debt” to be instituted.

Question 1c: Germany will force nations to bear their own debts unless that threatens their own banks and then the story changes.

Question 2a: Germany will never all a federal fiscal stabilisation function to be created. It might allow some weak unemployment insurance scheme and claim this satisfies the design deficiency (which it will not).

Question 2b: France and Germany will resist the creation of a federal fiscal capacity.

Question 2c: All nations will refuse to surrender their so-called ‘decentralised’ fiscal capacities, which, in fact, are an illusion, given the points I made above about the Stability and Growth Pact.

My answers to the legitimate questions posed by France Stratégie indicate that short of an orderly breakup (or unilateral exit), the Eurozone has a bleak future.

France Stratégie think there are three ways of dealing with the incoherent situation the Eurozone finds itself in.

Option 1. Return to the Original Principles, Complemented

This would force national governments to bear the “market discipline” in relation to their fiscal decisions with a strict no bailout clause being enforced.

France Stratégie conclude that this would require “adding on more restrictive rules” to ensure the bond markets take down governments that breach the fiscal rules, which will not be “a politically acceptable solution”.

That means, in short, that governments have to be allowed to become insolvent and the participating banks bear the cost of the defaults.

They propose that in this situation, banks should be forced to carry less sovereign debt and there should be mechanisms to facilitate “sovereign debt restructuring”.

And, it is obvious, that the “possibility of debt restructuring would likely amplify public finance crises, with a risk of strongly restricting the ability to respond fiscally in the event of an asymmetric shock”.

That is, back to square one. No solution at all.

Option 2. Further Progress in European Fiscal Integration

Accordingly, to reduce the risk that a nation will become insolvent:

… would require some form of joint liability on all or on part of member states’ public debt. The exact mechanism for implementing this joint liability is not that important: in each instance it is likely to lead to a permanent transfer of wealth from one member state to another in the event of a major crisis. In other words, this means taxpayers of one member state may be called on to bail out another country. This is not an undesirable side effect of joint liability; on the contrary, it is joint liability’s defining feature.

Try to imagine Germany going along with this!

France Stratégie recognise that any move (no matter how small) to “joint liability … would need to be under-pinned by more binding constraints on national budgets”.

The fiscal rules in place are already too restrictive and bias the Member States to pro-cyclical fiscal behaviour – which is, destructive and irresponsible.

Tightening the rules even more is ridiculous.

France Stratégie realise this will compromise democratic freedoms because “national budgets” would have to be controlled by “supranational scrutiny” which would be “legally binding at the national level”.

So all the nations become Greece!

And how would these nations respond to a large spending collapse in the non-government sector a la GFC?

France Stratégie claim there are two possibilities: (a) create “a centralized fiscal capacity”, or, (b) “through the coordination of national budgets”.

The nations categorically rejected the first option in the original Maastricht discussions and the cultural and historical rivalry is so great within Europe that I cannot see them ever agreeing to such a move – that is, to create a federal fiscal capacity with sufficient capacity to engage in transfers between Member States.

Germany will never allow it. France neither.

The second option doesn’t overcome the fact that tightening the rules, no matter how coordinated, push fiscal capacity further away from being effective.

Option 3. Combine National Autonomy and a European Federal Budget

They call this the US model where the states have some fiscal discretion and responsibility for their own debt but know that the US federal government has the fiscal capacity (spending and taxation) to defend the national economy from major downturns in non-government spending.

The US states know that “when a crisis does occur, transfers from the federal budget … provide some degree of macroeconomic stabilization.”

France Stratégie claim that this “setup could be replicated in the euro area to combine the desire to reinforce fiscal sovereignty at the national level – no longer constrained by European rules – and the need to create an instrument tasked with macroeconomic stabilization at the level of the eurozone.”

They put that quote in bold font.

Here is my response (also in bold font) – There is no way the Eurozone Member States will agree to a US-style federation.

It is obvious that an economic solution for the Eurozone is to bring the fiscal policy responsibilities (spending and taxation) in line with the monetary issuing capacity and allow the federal fiscal authority to run deficits commensurate with the non-government spending gap.

The necessity of this alignment was recognised by the Werner Committee in 1970 and the MacDougall Study Group in 1977 but was ignored, for ideological reasons, by the Delors Committee in 1989.

The – Werner Report – for example, concluded that for EMU cohesion “transfers of responsibility from the national to the Community plane will be essential” (Werner Report, 1970, page 10).

Moreover, the (p.11):

… transfer to the Community level of the powers exercised hitherto by national authorities will go hand in hand with the transfer of a corresponding Parliamentary responsibility from the national plane to that of the Community. The centre of decision of economic policy will be politically responsible to a European Parliament.

In a similar vein, the – MacDougall Report concluded in relation to the need for a mechanism to cushion “short-term and cyclical fluctuations” (p.12) that:

… because the Community budget is so relatively very small there is no such mechanism in operation on any significant scale, as between member countries, and this is an important reason why in the present circumstances monetary union is impracticable.

The current design of the Eurozone determines that the Member State governments are not ‘sovereign’ in the sense that they are forced to use a foreign currency and must issue debt to private bond markets in that foreign currency to fund any fiscal deficits.

Their fiscal positions must then take the full brunt of any economic downturn because there is no ‘federal’ counter stabilisation function.

The EMU is a federation without the most important component.

The Member State governments thus can run out of money and become insolvent if the bond markets decline to purchase their debt.

Among other things, this means the elected governments cannot guarantee the solvency of the banks that operate within their borders.

It is a basic characteristic of any monetary system that government can only create risk free liabilities if they are denominated in its own currency. The fact that the political leaders chose this design was astounding given it stood no chance of withstanding a major event such as the GFC.

The establishment of a full fiscal union would require the creation of a Federal Fiscal Authority which could certainly offer a relatively speedy solution to the economic mess.

Combined with the abandonment of the SGP, the federal fiscal authority could set about restoring domestic demand in the Member State economies through a combination of direct employment schemes, investment in improved education, health and training capacity, increased pension and fixed income entitlements where appropriate, and major public infrastructure projects including better and greener ports, airports and public transport systems.

The spending injections would kick start the regional economies, increase household and business confidence and inspire a private spending recovery as incomes and jobs became more secure.

It is likely that the federal fiscal authority would have to run fiscal deficits significantly higher than those allowed for under the SGP for an extended period, which means that any attempt to impose such fiscal rules would be self-defeating.

The establishment of a federal fiscal authority would address the major current constraints on recovery.

First, it would directly redress the stagnant spending conditions across the Eurozone.

Second, it would mesh perfectly with the proposal to create a full banking union. The federal fiscal authority would be uniquely equipped to ensure that bank deposits were not vulnerable.

Consistent with the observations made by the Werner Committee that a loss of national fiscal power to the centre should not undermine democratic processes, the federal fiscal authority should become responsible to the European Parliament.

There should be no capacity for the European Commission or Council of Ministers (Ecofin) to dominate this new ‘governmental’ body.

In Australia, for example, the Federal government regularly meets with the Premiers and Treasurers of the State governments, but the latter group are not part of the federal treasury nor do they have any role in the economic and finance ministries.

The role of the federal fiscal authority is to take a federal view of things rather than be a forum for deal mongering, which primarily reflects national level intrigues and enmities.

The notion of a federal fiscal authority also has implications for how public debt is issued and who is responsible for it.

It would be preferable if this new federal fiscal authority engaged with the central bank to use Overt Monetary Financing as a way to consolidate the fiscal policy responsibilities and operations of the federal fiscal authority with the monetary policy obligations and related liquidity management functions of the ECB.

But if the FFA chose to issue its own debt to the private bond markets to match its fiscal deficits, such debt would carry no default risk because they would be backed by the currency issuing capacity of the ECB.

The federal fiscal authority euro bonds would have the same risk free status as debt issued by the Japanese, US, UK, Australian and other ‘sovereign’ governments.

Debt issued by the Member States, for their own projects, would still carry default risk, but that could be significantly reduced through guarantees provided by the federal fiscal authority.

Another option could be that the federal fiscal authority uses its superior borrowing capacity to raise funds on behalf of the Member States using some sort of federal state partnership agreement.

All of these arrangements are, however, nuances of the overall fact that the creation of a federal fiscal authority with its own debt issuance capacity would solve the so-called sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone immediately.

The ECB could also easily subsume all the outstanding Member State debt and write it off as a new beginning. If there were a truly federal spirit operating, none of the ‘better off’ Member States would begrudge this sort of debt redemption.

The problem with this option is clear – it is not politically feasible. Germany, for a start, would never agree.

The MacDougall Study Group clearly understood this point.

An essential requirement for an effective monetary system with multiple tiers of government is that the citizens have to be tolerant of intra-regional transfers of government spending and not insist on proportional participation in that spending.

he other side of this coin is that a particular region might enjoy less of the income it produces so that other regions can enjoy more income than they produce.

To achieve that tolerance there has to be a shared history, which leads to a common culture and identity. For example, are the citizens of Berlin, Germans or Europeans in the first instance?

Language is an aspect of this, but not necessarily intrinsic.

In a successful federation such as Australia, people in the states of NSW and Victoria might occasionally complain that the smaller state of Tasmania gets a disproportionate amount of government assistance relative to its ‘tax base’.

However, there is no serious discussion that these federal transfers should stop or that the states with the weaker economies should be forced to endure a lower material standard of living than any other state.

Further, when there is a major dilemma facing one state (perhaps a natural disaster or a significant economic downturn), it is assumed, without question, that the federal government will offer financial assistance to the beleaguered state.

The point is that the citizens within an effective federal system have to share a common sense of purpose and togetherness to ensure that the monetary system works for all states/regions rather than those that have powerful economies.

That capacity and required tolerance is largely non-existent in the Eurozone, which is why talk of a fiscal union will be largely inconsequential.

An example of this political and cultural shortfall in Europe is the fact that politicians think it is appropriate to refer to large economies such as Spain and Italy as ‘peripheral’ nations.

The ‘core-periphery’ nomenclature came out of development economics, and the periphery referred to nations or regions which were underdeveloped or less developed, without basic infrastructure or human capital. Referring to rich civilisations such as Italy and Spain in this way indicates a deep malaise.

Moreover, it is not just the historical and cultural differences that are at odds with the idea of a fully integrated economic and political union.

For the federal fiscal authority to provide effective fiscal support for growth and prosperity in the Eurozone, a major paradigm shift in economic thinking is required.

When the old hatreds and suspicions in Europe combined with the emergence of neo-liberal economic thinking, the outcome was the Delors Report and the subsequent unworkable design of the Maastricht Treaty.

That mindset biases the Eurozone towards stagnation. A new way of economic thinking, which recognises the opportunities that a truly sovereign federal government has if it utilises its currency appropriately, is required.

If that way of thinking could emerge, then the design of the federal fiscal authority and its operational charter would follow easily.

The expectation would have to be, however, that there will be no paradigm shift in economic thinking forthcoming on a European wide scale, such is the grip that neo-liberalism has on the economics profession and the policy makers.

In that context, it will be easier for a single nation to exit and build a new culture of growth with a new economic policy making approach.

Conclusion

There is nothing irrevocable about the euro or the Eurozone. While there are no formal exit mechanisms established in the relevant Treaties, short of military occupation, Greece and Italy and any other nation can do what it likes.

Argentina showed in the early 2000s that it could take on the big financial market lenders and the multilateral bullies (such as the IMF) and restore its sovereignty for the benefit of its people.

Argentina’s derring-do approach humiliated the global power elites and invoked all manner of threats and scaremongering, none of which really gained any traction. Far from cowering to the demands of the IMF and the financial markets, Argentina took several bold steps to resolve its crisis through domestic expansion and employment creation. It largely worked.

The general point is that a nation that restores its own currency increases its options and alters the balance of power between itself and the financial markets. A nation can force foreign lenders to come bidding for a deal rather becoming captive to a Troika of predators working in the interests of the investment bankers and other corporate interests, without regard for the nation’s population.

Further, the way to deal the “markets and financial speculators” out of the game is to ensure there is an adequate regulative environment and that national governments are not dependent on funding from the private sector. That is:

1. Restore full currency sovereignty at the national level.

2. Educate governments at that level that they issue the currency that they borrow back which means they don’t have to borrow it back to spend. There might be other reasons they want to issue debt (central bank liquidity management operations, for example) but these are unrelated to the necessity to fund themselves in the currency they issue.

3. Ensure non-productive financial speculation which means about 95 per cent of all financial transactions are declared illegal or tightly controlled.

4. Make sure citizens elect governments not prevent the cabal of Euro elites interfering and installing their own cronies when the elected representatives appeal to the citizens for guidance in difficult times (by, for example, proposing a referendum).

Why did France Stratégie ignore those options? No need to answer!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Happy Christmas Bill! Keep up the good work!

Best regards

Great as always Bill….

Merry Christmas & Happy New Year…

What should we call our new currency? Looks like one is coming to Europe in 2017/18.

Z

There is a contest between the financier class and the vast majority of the people in almost every nation on earth and the financiers are winning because they have used their money and power to buy the mass media and the political class. They are a tiny minority yet a sizable proportion of the electorate choose to believe their lies and continually vote for more of their poison.

Brexit is the correct path for the UK as the Eurozone must disintegrate at some point and the only viable counter to the dissolution of nations, financialisation of the economy and plutocracy, apart from revolution, is properly functioning national democracy, national parliaments that legislate for the betterment of the lives of all citizens and governments that believe in equality of opportunity and realise the power of having a sovereign currency and their ability to ensure full employment.

It must be very frustrating to know the truth of this fraud and to know the solutions and yet in general continue to be ignored by the progressive side of politics and by the electorate.

Another fine article.

When the ECB began buying up debt (acting like a Central Bank for the EU) did they issue debt, euro dollar for euro dollar, to match what amounted to EU deficit spending? I’m trying to learn how large was this deficit spend.

Andreas Bimba – unfortunately, the Brexit camp here in the UK do not understand why it is good to leave the UK because politicians have not informed them accurately in the manner that Bill has in today’s blog.

In the UK, Brexit seems to amount to wrapping yourself in a Union jack and chanting a mantra ‘take back control.’ But they have no understanding of how control can be taken back and are fed lies and nonsense by right wing shysters who are often themselves part of the financial elites and want to dismantle the welfare state and say nothing about corporate power and financialisation.

Is it true though that the Eurozone mess benefits ANYONE?

From what I can see, government borrowing in a foreign currency is a lose-lose scenario. The bond holders get default risk and the citizens get austerity and crisis.

The Eurozone situation is bad but, around the world, many other countries have far worse situations as a result of USD denominated government debt. There doesn’t seem to be any widespread recognition that denominating government debt in a foreign currency CAUSES impoverishment. I keep being told that I’ve got it all the wrong way around and borrowing in foreign currency is simply an end point symptom of mismanaged governments that can’t use local currency because they lack fiscal credibility. Just look at this article comparing Singapore to Caribbean countries http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/2015/02/24/singaporean-lessons/. It totally ignores what to me is the elephant in the room in that the Caribbean countries are bled dry with USD denominated government debt.

You mention Argentina, BUT Argentina has gone back to issuing USD denominated government debt http://www.wsj.com/articles/argentina-returns-to-global-debt-markets-with-16-5-billion-bond-sale-1461078033 . Why do they do that? Why does Venezuela issue USD denominated debt?

I’d like to see a “decent-IMF” that consisted of an institution that advised impoverished countries on how to convert USD-denominated government debt into local currency denominated debt. I’d also like to see a popular campaign along the lines of the Jubilee 2000 campaign except that it campaigned for an end to the USD-denominated third world government debt system. I just get told I’m misunderstanding it all though whenever I bring the subject up.

I’m genuinely baffled both why so many countries issue USD denominated government debt and why well meaning economists (such as in SPERI ) insist that it isn’t an important factor.

“It must be very frustrating to know the truth of this fraud and to know the solutions and yet in general continue to be ignored by the progressive side of politics and by the electorate.”

Amen to that.

As always tireless work Bill.

Happy festive season. Don’t forget to play a bit of music 🙂

The French left is not up to the task they don’t understand the EU shortcomings well enough yet.

Stone- i think this is the key point in the SPERI article about Singapore:

“a highly interventionist state that purposefully shapes the contours of the country’s political economy in developmentalist ways, operating in tandem with an extremely open, freewheeling commercial brand of capitalism. This is why it has worked so well: a state and market in symbiosis, rather than conflict. In other words, while businesspeople are free to build fortunes and trade flourishes, the state retains an iron grip on certain critical functions.”

Regrading Venezuela – I’ve read that its regime is being destabilized by the U.S and that productive capacity has been falling which will keep devaluing the currency while producers sell goods abroad to neighbouring countries creating shortages. Political strife bordering on civil war seems to be going on as well.

I’ve also read that the Bolivar has a whole raft of exchange values depending on the goods it is used to buy -I can’t get my head around that but it sounds a mess. I imagine Bill will be aware of the technical issues going on there.

Chris Herbert,

“did they issue debt, euro dollar for euro dollar, to match what amounted to EU deficit spending?”

Unless someone here corrects me, the ECB acted like any other central and simply conjured up the money to purchase public sector debt issued by those nations that were in trouble.

The ECB is absolutely a central bank, in that they are able to conjure up any money they need from thin air to purchase any debt (private or public), and can hold that overall stock of debt until the end of time – or indeed, delete it.

Kind Regards

Dear Bill,

Appreciate your excellent and tireless efforts!

I hope you enjoy the festive season.

Simon Cohen, but Singapore is only able to have that mixed economy BECAUSE its government has a stable secure monetary system thanks to borrowing in Singapore dollars rather than using some foreign currency for government borrowing. Likewise, Venuezuela wouldn’t be susceptible to USA destabilization and have a sliding currency IF the government were borrowing in Bolivars rather than in USD. Do you disagree???

“They are motivated by the conclusion that the current situation is “ineffective”, which is a euphemism for total dead-in-the-water failure.”

Wow, Bill. So you do have a sense of humour. I nearly fell off my chair with laughter!

And there was me thinking that you are only a serious academic.

I stand corrected.