I will be working in the UK from February 19 to February 28, 2026. I…

Monday travel and some austerity stories

There is no detailed blog today as I am travelling from Brussels to Sydney. I will resurface again on Tuesday after the long flight. When I wrote my blog on Friday documenting the austerity tour around Porto I forgot to mention a few things. This blog adds some more observations I have made of conditions in this part of the world at present.

Please note that some comments might not be approved until late Monday (EAST) as I will have limited Internet access.

Some things I forgot to mention about Porto

Privatisation madness – Portuguese government sell its electricity company to the Chinese government

Remember all the arguments about how state-owned companies are less efficient than privately-owned and run companies because there is no share market discipline.

These arguments were at the forefront of the neo-liberal privatisation scams. The main electricity provider in Portugal – Energias de Portugal – which is also one of the Portugal’s largest business groups was finally sold off in December 2011 to the Chinese Three Gorges Corporation for the measly sum of €2.69 billion (acquired the Government’s remaining 21.35 per cent share).

Need I remind you that the Three Gorges Corporation is a “state-owned Chinese power company”.

The other main shareholder (10.13 per cent) is the ‘Capital Group’, which is a private US investment banking firm. Oppidum (7.19 per cent) and Black Rock (5.06 per cent) are other significant shareholders.

Another shareholder (2.27 per cent) is the – Qatar Investment Authority – which is owned by the State of Qatar.

The result of the final privatisation: higher power prices.

Portuguese electricity prices are now among the highest in Europe and well above the average. For example, in Lisbon (as at November 2013), it costs 26.99 euro cents per KWh relative to the average of 20.34 cents per KWh (Source).

Price rises under the newly privatised EDP have been well ahead of the inflation rate, although there have been some concessions made (under Government direction) to so-called ‘social tariffs’ which allow those on low or zero incomes to receive cheaper power.

To (over)-compensate for the social tariffs, EDP has hiked rates above the low income threshold significantly.

The reality is that Portuguese electricity is very expensive relative to real income levels and the workers are now suffering from the squeeze.

Eurostat data shows that between 27 per cent of Portuguese are unable to heat their homeadequately.

Innovations when income is short

I saw taxi drivers waiting in the queue at the taxi rank for customers push their cars up in the line when the first taxi takes off.

Income is tight in Porto and the pushing saves them petrol while they wait.

Photo Essay about the impact on youth of austerity

The old prison in Porto houses the – Centro Português de Fotografia (the Centre for Portuguese Photography).

Anyone who had the misfortune to be incarcerated in this building was in for a hard time. Access to the shared cells (large rooms) was by trapdoor in the roof. The building is all stone and the notes say it was very cold in the Winter.

After the revolution in 1974, the remaining prisoners were shifted elsewhere and the building fell into disrepair. It was renovated in the 1990s and now serves as a Museum for photography tracing the history of cameras, film and the craft.

It is well worth a visit if you are in Porto.

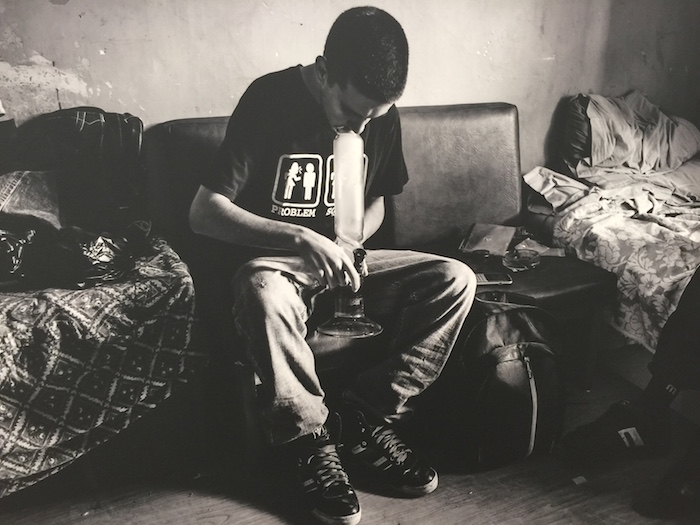

A current display considers a photo essay on austerity. The following sequence of photos displayed in this presentation are representative of what life for many young people in the North of Portugal is like now.

It was a three-panel display in the horizontal plane but so you can read the text I have enlarged the photos I took and arranged them vertically.

I believe the photos were taken by João Miguel Gomes e Silva, a Porto photographer.

The folly of the real estate/financial market nexus

The other day I said that it was hard to see the impacts of austerity and the GFC in the beach areas outside Porto. But further observation, near where I have been staying on the beach, is a failed real estate development, which was linked to the Espirito Santo Group (GES) disaster.

GES, the developers announced in late October 2013 that it was investing around 60 million euros on the venture that was meant to look like this. Of course, it wasn’t their cash but was to be added to the massive debt it was already holding.

It was meant to be a luxury beach front development on the southern bank of the Douro River where the top-end-of-town would be able to monopolise a key part of the local terrain with river and ocean views.

The sales gloss said that the development offered “excellent panoramic views of the Atlantic Ocean, Douro River and the city of Porto”. It was formerly part of the local food processing industry (a dried cod unit).

This is what they were planning to develop and make large profits from.

The 16 hectare site would have been a glorious location for a public park.

The Espírito Santo Group was a private company and so does not have to issue public records. So it is hard to trace the exact cause of its collapse.

The Espírito Santo Group collapsed in 2014 and the flow-on effects “led to a state rescue of Portugal’s second-largest bank in August” 2014, using bailout money from the European Commission and the IMF.

Reuters subsequently reported (December 11, 2014) that the company:

… was a financially fragile “house of cards” for years and its chief knew of irregularities there … the group’s financial situation was calamitous …

These revelations came out in a government inquiry into the “4.9 billion euro ($6.1 billion) rescue of” the – Banco Espirito Santo.

The bank was divided into two separate entities – a ‘good bank’ (Novo Banco) which retained all the viable assets and a ‘bad bank’ which held all the toxic assets.

It was bailed out by Portugal’s central bank in August 2014 and funded by the Portuguese Resolution Fund.

The Banco Espirito Santo was partly owned by GES but was heavily exposed, through a complex web of companies to other GES members (GES being the holding company for 300 other companies operating across 50 countries).

During the inquiry, it was revealed that the boss of the Banco Espiro Santo has been “manipulating accounts” to conceal debt exposures (Source).

It was also alleged during the inquiry that “the financial controller of GES, was probably also aware of the alleged manipulation of accounts” and GES was locked into a “debt spiral” that it could no longer service once things went south.

The collapse reverberated throughout the financial markets with creditors as far as Angola and Brazil losing heavily.

So as they were approaching their Armageddon they were still borrowing heavily and spruiking up business.

This is what the luxury estate looks like now. Nature is taking back the site and the roads, footpaths, drains etc that were constructed as part of the early development phase are becoming infested with weeds and other decay.

Conclusion

I will be back to more detailed blogging on Tuesday once I get home.

I have initiated a new research project as a result of my stay in Porto last week. It is true that many European nations started deindustrialising long before the crisis came and, in most cases, long before they entered the Eurozone. I am exploring methods to separate the effects of deindustrialisation out from the austerity.

Clearly in Portugal’s case, the suffering and demise has been driven by both events/processes. I have my thinking cap on!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I attended a Jeremy Corbyn rally tonight (Sunday 7th). He stated that we should not be deciding policy on “balancing the books,” but, (in so many words) on the needs of society, and he did not mention the deficit once!

Have you surfed Portugal Bill? The failed development site shows a solid little swell?

That’s encouraging. Let’s hope that isn’t just rhetoric, but a genuine shift in position within the Corbyn Camp.

The whole Corbyn phenomenon has been based upon being honest and consistent, and that means he has to observe “Lerner’s Law”. Otherwise the other side will rip the argument to shreds.

If you limit countercyclical intervention to the capital budget, it means you can’t look at education, training, research or any form of public service as countercyclical projects.

Eventually you end up building roads to nowhere to keep people engaged, which is a waste of resources.

“Eventually you end up building roads to nowhere to keep people engaged, which is a waste of resources.”

I agree Neil. It’s one of the reasons I am dubious about Job Guarantee. If there are jobs worth doing there will be people doing them. And furthermore if you are working on some created local authority job you don’t have the time to look for proper work. I was unemployed for 7 months in 1993/4 as a result of a car accident and in those days (I don’t know about now) unemployment benefit claimants were required to attend a weekly job-seeking session. There would be 20 or so unemployed at them, and I can tell you not one man or woman would not rather have been in work even though they would most probably have been financially worse off.

I am pleased to say that today a stretch of local road starts a £22 million 8 month full-depth resurface. Plenty of jobs where I live, though I do accept the same may not be the case in Northumberland.

Nigel

“If there are jobs worth doing there will be people doing them”.

Is that why our road infrastructure is falling apart?

Funny, though in Calderdale they seem keen on fixing the pavements just now.

Oh well, maybe I’ll start riding my pushbike on them to avoid the potholes and rough road surfaces everywhere around these parts.

I would very much like to know further details on that new research project. I hope it includes Portugal!

Thanks Prof. Mitchell for a most interesting view of the practical effects stemming from neo-liberal economics and politics. Really good news also from Sandy Crawford. Good short article on Lerner’s Law here https://alittleecon.wordpress.com/2015/09/04/lessons-for-corbyn-in-lerners-law/ (I confess I had to look it up – obviously haven’t read this blog closely enough).

In response to Nigel Hargreaves (comment above), I do hope that some of your thoughts and language are just misjudged rather than really believed. ‘If there are jobs worth doing there will be people doing them’ – can you really travel around Britain and say that there aren’t jobs that could be done to enhance people’s prosperity now and in the future and believe that the private sector, with it’s zero hours contracts etc (not just the private sector) is currently employing people in the best way for society? How do you define ‘proper work’? Do all private sector jobs fulfill this definition (but others don’t) as long as there is a wage involved? It’s a short step to using the cretinous description of ‘non-jobs’. As for people working in job guarantee jobs not having time to look for other paid employment, that suggests that these jobs would be more involving than the jobs which many people routinely transfer in and out of. On the other hand, your observation about most unemployed people wanting to work (and hence why the conservatives use such derogatory language about them) is quite right, though I think you mean ‘is not’ rather than ‘may not’ for your Northumberland comparison. Changing the neo-liberal groupthink is an arduous task and needs to be handled with careful language but we should be quite clear as to what is possible: unemployment is a government construct and no more natural than full employment.

“If there are jobs worth doing there will be people doing them”

This premise is totally wrong. In the private sector, (and ever more so in the public sector that is supposed to be run like a business), “worth doing” is defined as “profitable”. Yes, most jobs in the private sector that can be done profitably given the current conditions are being done.

However, whether or not something is “profitable” is not the main determinant of something that is worth doing in general. If the Govt builds a beautiful new park that is free to the public and enjoyed by thousands of people, is this project not worth doing because its not profitable? Or would this park be worth building only if you charged park goers enough money to offset the spending? When the Federal Govt has an infinite supply of currency, profitability is a completely irrelevant concept.

For the Govt with its infinite supply of currency, the value analysis is totally different than money in vs money out. The question becomes is this park socially useful? Would it be better to use this land for some other purpose (maybe more homes for the homeless?) Is there enough manpower and material available to do the project? If there isnt, is this project more valuable to society than whatever else it is that that material and those workers were doing? Is building this project here fair to other citizens in other national locales who arent getting a park? Or maybe its OK to build this park here as long as we build parks elsewhere too?

I’m sure the rest of the community can come up with lots of other variables that need to be considered, but do you know what none of those variables will be……do we have enough money, where will it come from, will we make more money over time than we spend on this project. These considerations are not very important.

Re de-industrialisation, that’s been going on for a long time. The the US the split between goods and services was 60% goods and 40% services in 1950. It’s now 65% services and 35% goods. But the pace of change has approximately levelled off over the last decade.

Brian,

I did qualify my statement by saying I don’t know about Northumberland. Same goes for Calderdale which is not far from Bradford. I know the area because I was at Leeds University – but that was 50 years ago.

I did also say a few days ago myself that the road infrastructure is falling apart, the buses break down and the railway rolling stock is ageing. That said there’s a fleet of Hitachi trains being built for the Great Western and East Coast Lines, and although they are Japanese most will be manufactured in the north of England near Darlington. Many components will be sourced from UK suppliers.

And what is a worthwile job? As Neil points out it’s no good building roads to nowhere. That isn’t worthwile. True a sovreign government can fund whatever it likes by using its currency-issuing capacity. It is nevertheless restrained by what is for sale. Roads to nowhere should not be for sale. Nice parks, fine.

The only reason investment banks like Goldman Sachs and the like are profitable is because governments have given them everything they wanted and more.

If government treated the Godlman Sachs’ of this world like they do the unemployed , then I doubt those pampered Armani wearing characters* would last a week fending for themselves.

[Note: * descriptor used in actual comment was replaced by Bill to be ‘characters’ so as to be less personally offensive]

“I agree Neil. It’s one of the reasons I am dubious about Job Guarantee.”

It’s nothing to do with the Job Guarantee. The Job Guarantee is unlimited, and can deal with revenue jobs in education, training, research and the service sector.

The PQE jobs are limited to the capital budget, which is particularly silly because we’d be better off inventing machines to do most of them, or automating them in factories. (Houses in particular are built in the most primitive manner imaginable – brick on brick. You never see a commercial building built like that).

The Job Guarantee is the Golden Eagle of counter-cyclical response – perfectly adapted to its niche. Compared to that, PQE is a bit of a dinosaur.