The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Greece should not accept any further austerity – full stop!

In the lead up to last weekend’s Greek referendum there was an extraordinary flurry of opinion pieces in newspapers around the World which sought to blame Greece for its own situation. Among the most ridiculous of these articles was the one which appeared in the British Independent (July 1, 2015) – Get off your high horses, lefties – Big Government, not ‘austerity’, has brought Greece to its knees . Apparently, left-wing views dominate the shelves of any mainstream bookstore in the UK and represent the mainstream economic opinion. It raises the question of which planet the writer is on! The writer also claimed that Syriza is just another leftie political party in Greece, in a long tradition of such parties, committed to “economic statism and hyperinterventionism”. And the current crisis is actually the result of decisions taken in the 1980s to build “up a huge client state” rather than surrendering the currency sovereignty in 2001. This blog explains that the Greek problem is one of insufficient spending. The fiscal deficit has to rise to stimulate growth. This problem emerged in 2008-09 and is largely due to the fiscal austerity that was imposed on the nation by the Troika. It might have crony deals and all the rest of it, but that is not what brought the economy to its depressed state. That state is all down to human intervention from outside of Greece in the form of austerity. Greece should not accept any further austerity – full stop!

To repeat myself (for the nth time, where n is a large number):

A basic rule of macroeconomics is that spending equals income, which leads to output and employment.

Someone’s spending is another person’s income. There has to be growth in spending for income and output to grow.

If there is unemployment it means that total spending is insufficient to generate enough output and hence jobs to satisfy the preferences for work of the unemployed.

The solution is always for the government to either directly increase spending to lift sales in the private sector and stimulate further income and/or to cut taxes, which might lead to higher private spending.

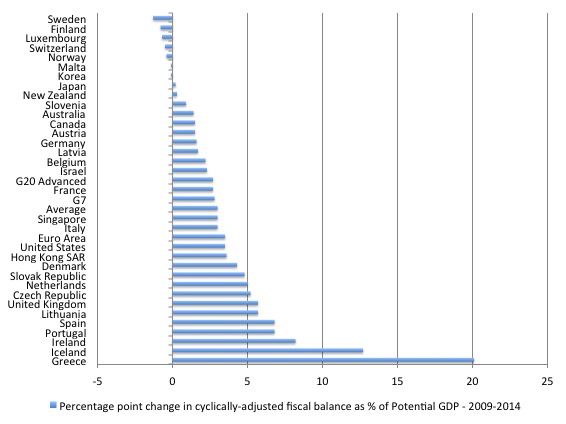

There was an interesting graph circulated on Twitter today showing the extent of fiscal shift in a large number of nations. Here is my version of the same graph.

It shows the percentage point change in cyclically-adjusted fiscal balance as a percent of potential GDP from 2009 to 2014. The data is available from the latest edition of the IMF Fiscal Monitor – Now Is the Time Fiscal Policies for Sustainable Growth – published April 2015.

A positive result represents cuts in the size of the fiscal deficit and a negative result means the fiscal deficit increased. This shows the changes in the fiscal balance that arise from the discretionary policy changes made by the national governments net of the cyclical situation (actual relative to potential) that the nation finds itself in.

The graph’s data is for the IMF’s measure of the cyclically-adjusted fiscal balance (aka structural fiscal balance) and is likely to overstate the true ‘structural’ balance because they typically underestimate the cyclical effects on the balance for reasons discussed below.

So in the case of Greece, there has been a massive discretionary fiscal shift of 20.1 percentage point change (that is, unprecedented and massive) in the fiscal balance as a result of the austerity inflicted on the nation by its government. Yes, its government under the bullying of the Troika.

So in 2009, Greece’s structural deficit (as measured by the IMF) as a percentage of its estimated potential GDP was 18.6 per cent. By 2014, this had changed into a surplus of 1.5 per cent.

The shift in Iceland, while dramatic, has to be understood in the context of other policy changes that the Icelandic government made during the crisis to attenuate the impact of their fiscal retreat. At least they understood that spending creates income.

To fully comprehend what the data is showing we need to understand what a cyclically-adjusted fiscal balance is and what it means. Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

By way of quick summary:

1. A national government fiscal balance is the difference between total revenue and total outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the fiscal balance is in surplus and vice versa.

2. Many think that if the fiscal position is in surplus then the fiscal impact of government policy is contractionary (withdrawing net public spending) and if the fiscal position is in deficit then the fiscal impact is expansionary (adding net public spending).

3. But the measure is impure because it conflates two quite separate influences: (a) discretionary policy choices of the government; and (b) the effects of the economic cycle which alter tax revenue and spending without any change in policy settings (the so-called automatic stabilisers). Therefore we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal balance reflect discretionary policy changes

4. To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the ‘Full Employment Budget’ position but, in more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance or the cyclically-adjusted fiscal balance. This measure is a hypothetical construct of the fiscal balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the fiscal position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminates the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

5. The controversy lies in how to measure full capacity or potential output. The IMF, for example, use techniques that have the economy reaching full employment (with associated unemployment rates) well before the levels of output that I would consider to be potential. In other words, their estimates of the full employment unemployment rate are always too high.

6. The impact of that bias, is that their estimates of the cyclical component is always to small and the structural component too large.

7. As a result, they systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal austerity.

I decided to provide some further insights into this dataset by combining it with some – IMF World Economic Outlook data – showing shifts in the real economy (average Real GDP growth, Changes in Unemployment and Changes in the Investment Ratio), so see if there were any interesting patterns.

Of course given the basic rule of macroeconomics stated at the outset we expect large fiscal contractions (discretionary) measured by positive changes in the structural (cyclically-adjusted) fiscal balance to be associated with large rises in the unemployment rate, lower investment ratios and lower average real GDP rates.

We would expect the opposite to be the case.

So when the government is pursuing a discretionary stimulus (negative fiscal shifts – deficits getting larger), we expect average real GDP growth rates to be larger, unemployment to fall further and stronger private investment ratios.

Here is some cursory graphical evidence to support those contentions.

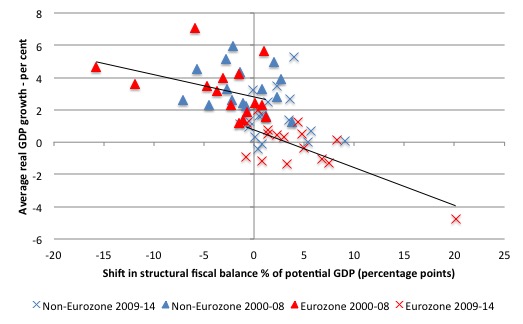

The first graph shows the shift in structural fiscal balance as a % of potential GDP on the horizontal axis and the average real GDP growth rate on the vertical axis. I divided the data into two periods: 2000-08 and 2009-14 and divided the sample into Eurozone nations and non-Eurozone nations. The solid black lines are linear trend regressions associated with the Eurozone data (for the two periods).

The results are pretty clear and more detailed modelling would not contradict what you can see with your eyes.

There is a negative relationship between discretionary fiscal contraction and average real GDP growth. When fiscal policy is in stimulus mode (a negative shift in the fiscal position), average growth rates are stronger.

Prior to the crisis, there is not much difference in the average growth rates of the Eurozone nations in the sample and the Non-Eurozone nations. Those with larger stimulative fiscal shifts enjoyed stronger growth.

After the crisis, the impacts of fiscal austerity are also fairly clear. The relationship shifts in slope, which means that for a given fiscal contraction, the negative impact on average real GDP growth is larger.

It is also clear that the Eurozone nations endured lower average real GDP growth rates over this period and dominate the negative growth observations.

Greece, is looking very lonely out there to the right of the graph.

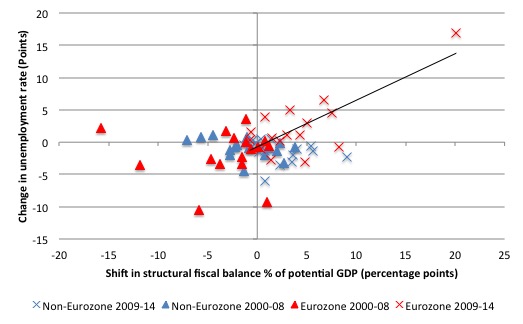

The next graph shows the relationship between the fiscal shifts and the change in unemployment rates (vertical axis, in points) for the same two periods as above.

The solid black lines are linear trend regressions associated with the Eurozone data for the austerity period. It is very steeply upward sloping which tells us that the larger the discretionary fiscal contraction the larger the rise in the unemployment rate. It is a clear cut relationship in the Eurozone.

Those absent Ricardians

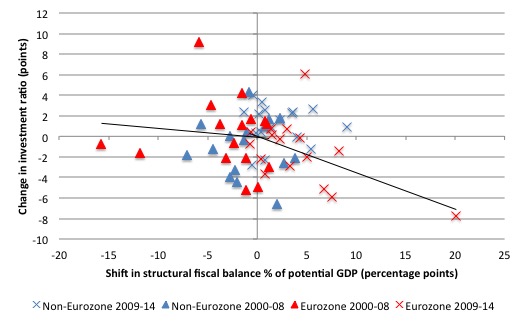

The data also allows us to graphically-speculate on whether private investment responds favourably to fiscal cutbacks as the mainstream economic theory claims.

Remember, the Monetarists – the intellectual (if you can call it that) forebears of the Eurozone neo-liberals, rejected the simple rule of macroeconomics and claimed instead that government spending and deficits were inflationary and wasteful.

As an alternative, they introduced the rather bizarre turnaround in logic that said that when there is unemployment the correct strategy for government is to cut its spending, that is, introduce what is now popularly known as ‘fiscal austerity’.

This policy view was based on an arcane theoretical notion that economic textbooks promote called ‘Ricardian Equivalence’.

It sounds scientific, but it is anything but. In simple terms it refers to the assertion that private spending is weak during a recession because households and firms form the view that the government will have to increase taxes in the future to pay back the debts it incurs due to the higher deficits.

As a consequence, the households and firms deliberately stop spending and save up to ensure they can pay the higher taxes.

Once the government starts to cut the deficit, the theory claims that a signal is sent to the private sector that future taxes will be lower and so they start spending again. Problem solved.

The only problem is that there has never been any credible empirical evidence produced by anyone to show that private households and firms behave in this way when deficits rise.

The overwhelming evidence shows that firms will not invest while consumption spending is weak and households will not spend because they are scared of becoming unemployed and try to minimise their outstanding debt obligation.

Ricardian agents only exist in the rarefied world of mainstream macroeconomic textbooks and have never been observed at large in the real world.

The following graph shows the change in the investment ratio (in points) – so the change in total private capital formation expressed as a percentage of GDP over 2000-08 and 2009-14 against the fiscal shift corresponding to those two periods.

The data shows that there is a negative relationship overall between fiscal policy contractions and the change in the investment ratio. The larger is the discretionary fiscal contraction, the larger is the fall in the investment ratio. The relationship for the Eurozone (summarised by the two trend lines) worsens after the austerity is imposed for reasons discussed above.

Presumably, the plunge is that consumer sales fell so quickly and substantially, that firms could meet demand for the foreseeable future with no increase in capacity and formed expectations that were so pessimistic about the future as austerity was ravaging growth that the incentive to invest fell sharply.

That is exactly the opposite to what we would expect if the mainstream theory was an accurate guide to socio-economic behaviour.

Alas, all those alleged ‘Ricardians’ turned out to be normal people scared of unemployment, sufficiently knowledgeable to know that deep fiscal austerity is bad for the economy and pessimistic when sales and incomes drop.

No surprise in that.

The surprise is that the economics profession continues to teach these myths.

The data shows that there is a negative relationship overall between fiscal policy contractions and the change in the investment ratio. The larger is the discretionary fiscal contraction, the larger is the fall in the investment ratio. The relationship for the Eurozone (summarised by the two trend lines) worsens after the austerity is imposed for reasons discussed above.

None of these results support the view that firms like contractions in fiscal deficits.

Conclusion

So while our columnist in the Independent would like to think the ‘lefties’ represent the mainstream, I think he should consult the economics textbooks that proliferate in undergraduate and graduate courses around the world.

Those textbooks tend to deny what you are seeing with your own eyes in these graphs and which more formal modelling would ratify.

The simple point is that the Eurozone is suffering from a dramatic shortage of total spending and the misguided fiscal austerity that was imposed on the Member States clearly undermined private investment spending and caused real GDP growth to fall and unemployment to rise.

Exactly the opposite of what the IMF was saying in 2009 when it was demanding that nations impose the austerity.

Fiscal policy rules. Greece is where it is at present because it was forced to endure the worst austerity (fiscal shift) imaginable.

There is no secret as to why its economy has contracted by at least 25 per cent and its unemployment remains stuck around 25 per cent.

What the data does emphasise, however, is the Greek government should head to Brussels today with a fiscal stimulus plan and forget about the debt relief for the time being. Its priority should be to get an agreement whereby it can run a significantly large fiscal deficit funded by the ECB through the QE program (that is, indirectly given the stupidity of the Treaty) to get the economy growing again.

The fact that the Syriza government was stating it would accept conditions that still left it to pursue primary fiscal surpluses (that is, once interest payments are made) tells me that it would be just another Greek government imposing austerity on its people.

It is not the debt relief that matters in the coming months but the ongoing austerity.

That is what the people voted NO for – to end the fiscal austerity. Syriza should demand that now and not backdown and accept some watered down austerity (at best).

Advertising: Special Discount available for my book to my blog readers

My new book – Eurozone Dystopia – Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – is now published by Edward Elgar UK and available for sale.

I am able to offer a Special 35 per cent discount to readers to reduce the price of the Hard Back version of the book.

Please go to the – Elgar on-line shop and use the Discount Code VIP35.

Some relevant links to further information and availability:

1. Edward Elgar Catalogue Page

2. You can read – Chapter 1 – for free.

3. You can purchase the book in – Hard Back format – at Edward Elgar’s On-line Shop.

4. You can buy the book in – eBook format – at Google’s Store.

It is a long book (501 pages) and the full price for the hard-back edition is not cheap. The eBook version is very affordable.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Just a quick (newby style) question……..would appreciate it if anyone out there could tell me if I’m getting what’s happening here……..

Is it true to say that Germany isn’t actually giving Greece any money, that the money is simply being created from nothing by the ECB free of any cost or risk (other than the potential for inflation in the future)

The author of the Independent article is a very young chap, Kristian Niemietz. The following bio-bite has been taken from the Independent’s biographical comment about the author.

“Dr Kristian Niemietz is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), and author of the books ‘Redefining the poverty debate’ and ‘A new understanding of poverty’. He holds a PhD in Political Economy from King’s College London, and an MSc in Economics from Humboldt Universität zu Berlin.”

The views in the article are not unusual for someone educated in neoclassical economics in the UK, found in PPE at, say, Oxford. UCL’s economics department, not far from King’s, had only one Keynesian on their staff, Victoria Chick, and she is retired. While it is possible to find heterodox economists in economics departments in the UK, they appear to be in the minority.

Dear Bill

The policies imposed on Greece are also a total failure from the point of view of Greece’s creditors. After all, the Greek debt is bigger now than it was 6 years ago, both in absolute numbers and in percentage of GDP. If you owe me a lot of money and I demand some changes in your behavior, which end up making you much poorer and also increasing your debt to me, then I’m doing something wrong.

Still, it can’t be denied that for many years before 2008, the Greeks did live far above their means. This would not have happened on the same scale if they still had had the drachma. The euro lowered interest rates drastically in Greece, and those cheap interest rates induced the Greeks to borrow wildly.

Regards. James

Being a poor uni student I was wondering how long this voucher lasts? I wont be able to buy this hard copy until December and I am really interested in reading it.

Thanks if you could tell me if It will still be available by then

Dear James Schipper

[Bill deleted personal abuse – please refrain as per comments policy]

You made the comment:

“The euro lowered interest rates drastically in Greece, and those cheap interest rates induced the Greeks to borrow wildly.”

In a floating fx fiat currency (like the Drachma was before the Euro), the interest rate is a policy choice. Lower Euro era interest rates than the drachma era interest rates, then this had nothing to do with actual economics and was solely a political decision (albeit informed by economic myths about how CBs can control the economy through interest rate adjustments). So there is no reason whatsoever to believe that Greece’s interest rate between 2000 and today would have necessarily been higher than the rates chosen by the ECB (understanding that Greek TSY securities denominated in Euro would most likely have a higher average rate given the official interbank rate than Greek TSY securities denominated in Drachma given the higher default risk associated with the former). Why would the drachma rate necessarily have been higher than the average Euro rate of 3.1%?

[Bill deleted further personal abuse]

Greek interbank rate under drachma in 2000:

Average for the year = 7.46%

Average for the month of Dec (last month) = 6.16%

rate on the last day of the Drachma = 4.42%

http://www.bankofgreece.gr/Pages/en/Statistics/rates_markets/oldrates.aspx

Euro interbank rate in January of 2001 = 4.8%

Average Euro interbank rate between Jan 2001 and the GFC in late 2008 = ~3.1%

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/euro-area/interest-rate

@Barzini – that is fiat money. Its just a data entry a central bank can instantiate 1 million euros in a keystroke.

ECB spends by keystrokes, has authority over the euro but does not control the total amount of euros in circulation. Worth reading a bit more on this blog or warren moslers free book (see links on right hand site of bill’s site to get the basics).

Worth reading about inflation too as that is a grossly mis-understood topic (bill has an inflation 101 blog entry or two).

By corollary the commercial ‘endogenous’ banking system money system creates ‘loans’ by keystroke so when a greek person was persuaded by a 5% interest rate to go into debt on a loan that money was created from nothing other than the evaluation of a person credit worthiness too. Hence why you hear the terms ‘pro-cyclical’, ‘bubble’, and ‘junk debt’. And in no way is the german tax payer ‘giving’ money to the greeks. Read bill’s blog on what tax is to understand that point.

cheers

Hello Auburn Parks

With reference to your message posted on Wednesday, 8th July 2015 at 12:29am, is it really necessary and constructive to speak to people in such a rude and aggressive manner? I realise that Bill has approved your post, and it’s up to him and him alone, but I find it very dismaying when high quality websites like this one degenerate to the level that much of the internet appears to exist on all day long. I don’t accept that the only way you can make your point with strength is by speaking insultingly and disparagingly.

Hello James Schipper

You wrote that “The policies imposed on Greece are also a total failure from the point of view of Greece’s creditors. … If you owe me a lot of money and I demand some changes in your behavior, which end up making you much poorer and also increasing your debt to me, then I’m doing something wrong.”

I agree with you, however it seems to me that the German government and its allies are motivated by something other than getting their money back.

We have all witnesses how everyone has always capitulated to the EU project and its forerunners (EC/EEC etc). Based on past experiences, there is no reason whatever for the EU project’s leaders to suspect that anyone, anywhere in Europe, is strong enough to resist them.

Regards

Jim

Thanks Bill

This is the type of thing I was asking for on the Sunday Quiz answers bolg

Powerful article by George Monbiot in today’s Guardian:

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/07/greece-financial-elite-democracy-liassez-faire-neoliberalism