It is my Friday Lay Day blog and it is going to be relatively quick. There was an article in the Wall Street Journal (December 23, 2015) – Economists Say ‘Bah! Humbug!’ to Christmas Presents – that says a lot about how my profession struggles to appreciate reality in all its dimensions. Every year, it…

Friday lay day – public spending is not necessarily matched by tax revenue in the long-run

It is my Friday lay day and that means brevity, even if that is a relative concept. I have received several E-mails lately about claims that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists are zealots who overstate their case and are nothing much more than Keynesians with some fancy jargon. It is lovely how complete strangers feel it is their place to write abusive E-mails to you as if you are some sort of inanimate object. But that is not the point here. Several of these E-mails noted that a prominent Australian economist had largely dismissed MMT, despite his progressive leanings, because “it doesn’t change the basic equation that, in the long run, public expenditure is paid for by taxes”. Apparently, this criticism was made in the context of the Russian problems at present, which I may or may not deal with in another blog, depending on whether I get time to research a few things. The Russian situation is not central to my research at present and I do not have a lot of time to really delve into it. But what about this “long run” failing of MMT?

First, in relation to Russia or any other nation that is suffering problems that come from its external sector I say the following. MMT is not a religion. It is not a panacea. It is not a policy code. It is not a solution.

MMT is a way of thinking about modern monetary systems. I am currently working on a new book which will trace the evolution of MMT – its antecedents (the shoulders the current proponents have stood on) and where it differs, say from the Keynesian thinking that was dominant in the Post WWII period up until the mid- to late 1970s. It will be published by Edward Elgar in late 2015 and is progressing well.

MMT provides an organising framework for understanding the possibilities available to a currency-issuing government and the limitations that a currency-using government (such as a Member State of the Eurozone) faces. It allows us to understand in a deeply-grained way, the relationships between the treasury and the central bank and the relationship between the government sector in aggregate and the non-government sector.

No ‘Keynesian’ literature up until the 1990s (or beyond for that matter) provides the level of granularity that the MMT literature that we have developed over the last 20 years provides. But all that will come out in the book.

A common misconception seen in the derivative literature on MMT (which is dominated these days by blogs, social media pages and tweets) seems to think that MMT says that currency-issuing governments are omnipotent and can solve any crisis just by spending. None of the main proponents of MMT over the last 2 decades has ever made statements to justify such a view.

A nation that has a narrow industrial base, has one dominant source of export revenue (for example, oil) which experiences significant price volatility, and relies on imported food faces significant real constraints if the export revenue collapses.

Then superimpose politically-motivated embargoes on that nation’s ability to import goods and services and the situation becomes highly problematic.

Even if that nation’s government issues its own currency, all that means is that it can buy and bring into productive use any real good and service that is for sale in the currency it issues.

It cannot buy imports that are for sale in another currency. It cannot set the terms that govern the exchange of its own currency and other currencies it might need to buy those imports.

Such a nation then may turn out to be very poor in material terms if its export revenue fails and the currency-issuing government cannot easily expand the real resources available to alter that state. The government can only ensure that all the real resources it can purchase are being used to their maximum, if that is a desirable outcome. But that is the limit of its currency-issuing capacity.

A nation with limited real resources has limited prospects for material welfare. That is the fact. The constraint is real and the infinite financial capacity the government might have in its own currency cannot alter that.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) provides no further understanding than that in these sorts of cases.

And what about the claim that “in the long run, public expenditure is paid for by taxes”? The concept of a ‘long-run’ is very mainstream for an economist to invoke and progressive economists should use the term (and underlying concept) guardedly (preferably not at all).

I discussed the mainstream notion of the long-run in this blog – The spurious distinction between the short- and long-run.

The late Polish economist Michał Kalecki, a contemporary of Keynes and who developed an understanding of how the economic cycle works in much more detail and richness than that presented by Keynes in his General Theory, rejected the notion of a long-run.

He was arguing against the classical/neo-classical notion that such a long-run state can be conceptualised where equilibrium rules and the ‘true’ nature of relationships are revealed including the ineffectiveness of government policy to alter the real outcomes that the market produces.

Any discussion of the long-run in Kalecki’s work contains no notion that the long-run is a steady-state attractor (that is, a (natural) point that the macroeconomy gravitates to when imperfections are eliminated).

Kalecki’s notion of the long-run bore no insinuation of “equilibrium” (competitive equalisation of rates of profit; realised expectations; full employment).

In effect, while his position shifted (in nuances) throughout his life, Kalecki rejected the mainstream view that there was a state we might call the long-run, which was separable from the economic cycle.

Kalecki said:

In fact, the long run trend is but a slowly changing component of a chain of short run situations; it has no independent entity …

That is the long-run is just a sequence of short-runs. And that these short-runs are all linked by path-determinancy – so you are today where you have come from. Effective demand (with investment as a major variable component) drives output and employment, but, in turn, influences investment (through expectations and profit realisation), which determines the path of potential output.

But it seems that this MMT critic wants to hang on to the notion of a definable long-run. I hope that this economist announces to the world when we get there!!

A tax is a particular policy tool. What MMT demonstrates is that it is one way in which fiscal policy can reduce the net worth of the non-government sector.

The transactions (building on yesterday’s blog – Central banks can sometimes generate higher inflation) – that accompany a tax payment are as follows:

1. The individual being taxed experiences a reduction in their bank deposit accounts and an equal decline in their net financial worth as a consequence.

2. The bank where the individual’s account is located reduces the individual’s deposits as it reduces its reserves.

3. The central bank, on behalf of the treasury, reduces private bank reserves and credits the treasury tax account (which, conceptually, for a currency-issuing government is intrinsically a rubbish bin!).

So tax revenue has specific meaning in terms of its effects on non-government net worth. Recall, that if the treasury issues a bond to match a fiscal deficit, the transactions that accompany that operation do not result in any reduction in non-government net worth – the individual purchaser of the bond experiences a reduction in bank deposits (asset loss) but an equal gain in bonds (asset gain). The operation is thus a change in the composition of non-government financial assets.

In that sense, a bond issue is a fundamentally different type of operation than a tax.

Further, if the central bank was to purchase the treasury debt then it just credits one account held by treasury (cash) and debits another (bond liabilities) and that is all there is too it. A shift in accounts within the government sector.

Neither operation (relating to bond issuance) is like a tax and so it would be misleading to claim that they represent a tax.

Now consider, the US, as an example, where the – Office of Management and Budget – provides very detailed – historical records – of the fiscal aggregates.

From – Table 1.1-Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-): 1789-2019 – we can get a pretty good idea of what has happened over a very long historical period.

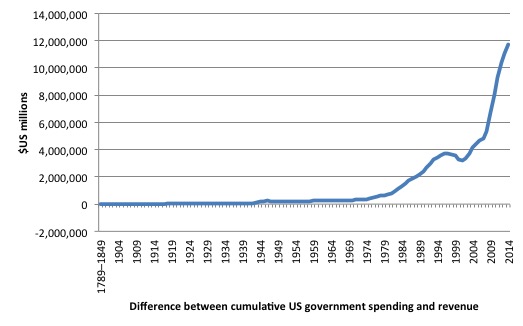

Here is a graph of the difference between cumulative tax revenue and cumulative federal spending in the US since 1789. The US started to run fiscal deficits systematically in 1931 and since then has run deficits 85 per cent of the time. Every time they had tried to run surpluses a recession has followed.

Note the gap widens after the early 1970s, which of course is when the Bretton Woods system of convertible currencies and fixed exchange rates was abandoned and the US government adopted a fiat currency system.

It seems that public spending is not paid for by taxes over a long period of time. Funny about that!

I could write a lot more but today is my lay day! So that is it.

Cuba

The US has finally abandoned its ridiculous policy towards Cuba, although probably for the wrong reasons given that the US President claims they are acting “because it will spur change among the people of Cuba, and that is our main objective”.

As if the US has any legitimate claims to be the model that other nations might wish to follow. But that is another discussion.

Ry Cooder, one American who defied the US boycotts to record in Havana in 1997 gave an interview to Time Magazine this week (December 17, 2014) – Cuba Decision ‘Is What We’ve Been Hoping Obama Would Do’.

He said:

Our leading export is this myth of democracy we have. That’s the leading edge of our export efforts. So how can we say to the American people, You can’t do it? The people will go when they want to go! A lot of people went. It’s a trend, a tendency, something that can’t be stopped. The more people want to join up with other people-Pete Seeger suggested that music was a bridge between classes. He used folk music as a bridge because it’s common to people and it’s easy to learn. He could have people singing together within five minutes. And I’ve seen that happen many times, but never so graphically as within this Buena Vista thing. You may be afraid of Cuba. Are you afraid of Rubén González when he plays the piano? No? Well that’s one less thing you’re afraid of.

The next step is (as Ry Cooder notes) for the US to “get rid of Guántanamo” and prosecute all the CIA torturers and politicians that let them get away with those human rights abuses.

Anyway, the changes will probably make things better for the Cuban people so to celebrate that here is my song for today from The Buena Vista Social Club – Candela (Fire).

You can groove to the double bass alone much less the rest of it.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Cuba is a classic case of self inflicted misery.

“The constraint is real ”

This is what I keep saying ad nauseam. Forget about the money. We know how to make a dynamic currency system operate so that it can deploy real resources.

So let’s concentrate on the real resources, take stock of them and look at what we’re doing with them.

What I find annoying are those people who really, really believe in the ‘Holy Power of Taxation’. The ‘Holy Power of Taxation’ will not cause a fully staffed hospital to appear by magic overnight. You have to have the trained doctors. you have to have the trained nurses and ancillary staff. You have to have the skills and capital capable of creating a hospital. All real things that are in short supply.

Unfortunately the ‘Holy Power of Taxation’ has actually become a metaphor for hurting somebody you don’t like. The appeal that you may be able to ‘do something’ afterwards is the excuse that justifies the violent thoughts.

Once you start to look at things in real terms, you gain a different viewpoint. Just as when you consolidate the Treasury and Central Bank you get a different viewpoint on monetary operations.

In real terms you can ask the right wing who is going to hire the public sector workers you are firing, and ask what are they going to do that is so much more important to life than what they are doing at present. Get underneath the money and you can lift the abstraction veil they like to put on people that turns them into ‘resources’ rather than the human beings that they are.

Forcing them to think in real terms stumps them. They can’t do it. They can’t answer the questions. Questions that actual people can relate to.

MMT probably has the most inappropriate name imaginable because ultimately the valuable insights are not modern – credit is as old as transacting humans are – they’re not really about money – the view on using real things is much more important – and they are certainly not theoretical – because the money system description is a fact.

The biggest lesson from MMT is: let’s stop talking about money.

In the UK the problem is that our glorious history of fighting the French was based on the King/Parliament borrowing from a private Bank of England backed by metal in the vaults and future tax revenues.

What people don’t seem to realise is that if we had not had an industrial revolution going on during the Napoleonic wars, the metal would not have been there and we would now all be eating snails and croques monsieurs. So it was ultimately down to real economic activity creating the cash to pay the wages of the soldiers and the subsidies to allies that allowed us to escape that fate.

The key seems to be in explaining to people that once all ties to metal went and the fact that the Bank of England is now part of Govt, everything changed but, as before, the important thing is creating real resources, and putting available productive capacity to work.

“A nation that has a narrow industrial base, has one dominant source of export revenue (for example, oil) which experiences significant price volatility, and relies on imported food faces significant real constraints if the export revenue collapses.”

UK

A nation that has almost no industrial base, has one dominant source of export revenue (for example, financial services l) which experiences significant price volatility, and relies on imported food faces significant real constraints if the export revenue collapses.

Bill talks about free floating currencies as if they are not manipulated at a vary high level.

At the moment the present flux in workwide exchange rates benefits England as it can import goods ( for example now cheaper euro food products previously destined for now sanctioned Russia )

In the UK energy trends publication for September it charts another massive decline of the now rump UK coal industry / production while almost half its coal imports remain Russian steam coal…..

December UK energy trends publication out this morning….. covering q 3…

Imports of electricity (mainly from stagnant nuclear France) at record 21st century highs at 7% of total.

LNG imports up 125 % relative to Q3 2013.

The UK and Japan are the primary customers for Qatar LNG – if Japan goes into recession that means the UK can buy more of the stuff.

Given the precarious nature of the UK’s import reliance its in the national interest to promote European and global depression using their banking gunboats as their primary tool.

The long run does exist. This is illustrated by irreversible processes. These irreversible processes exist in contra-disinction to reversible processes and cyclical processes. The using up of earth’s non-renewable resources by our economy is an irreversible process. This process has economic causes and will have feedback economic effects. On earth today, rapid species losses (a new mass extinction) is occurring due to the modern economic sytem. These species losses represent an irreversible complexity loss and irreversible damage to the holocene ecosystem. The economy does have a long run trajectory. This can be demonstrated from physics (thermodynamics) and the ecological sciences.

Of course, classical economic is wrong if it postulates the long run as an equilbrium. This is so unless they are referring to the possible heat death of the universe! But after all, there could be no economy under heat death conditions. The universe would be in thermodynamic equilibrium and objects could do no physical work.

Coming down to earth, the long economic run does exist. Irreversible historical transitions to new systems illustrate this; the feudal age was followed in succession by the mercantile era, the capitalist era and now the monopoly-finance capital era. These changes were and are qualitative as well as quantitative. These changes were and are also accompanied by irreversible changes to non-renewable resource stocks and ecological stocks including the irreverisible, irretrieveable loss of the “specific complexity” of holocene ecology. Even if collapse or regress occurs (very likely in fact) it will not be like a film in reverse taking us back through the eras. “Regress” is still a forward time movement. The starting conditions of a new “lower era” which might superfically resemble a previous “lower era” will this time be the exit conditions of a “higher era” not the exit conditions of even earlier era. You only have to look at deforrestation and the dying oceans to see that the exit-entry conditions for new old eras (new regressive eras) will be very different.

Secular or long term trends do exist even if we restrict ourselves to modern economics or political economy and ignore physics and ecology. Marx’s predictions about late stage capitalism are being borne out. A crisis of capital over-accumulation and increasing monopoly is occurring and has been occuring since the late 1960s. The long run trend to stagnation proves this. World growth has dropped from the six percents in the 1960s to the two percents today. This long run trend could only be changed by a change of system (say to worker cooperative socialism) or within capitalism only by massive wars (to destroy a lot of capital especially fixed capital) or maybe by a strong Keynesian or MMT-ian program with a switch back to democratic socialism, welfare and an increased wages share in the economy. But in all these scenarios the wolf at the door is limits to growth. It is the bete noir which guarantees there is no way out of capitalism’s final crisis and that a new and very difficult era will arise. The arrow of time is forward and the long run does exist.

I have seen the future. It is like a different past… without the resources.

The speaker here is a person that simply cannot grasp that spending precedes taxation. This is a person who cannot see the accounting that underlies all movements of money; indeed does not understand that accounting underlies all movements of money. I’ve often thought that non-MMTers could be “cured” if only they were made to express their models using the rules of accounting, including of course the requirement that their models actually balance.

Introduction.

The competing propositions are;

(A) Spending precedes taxation. (MMT)

(B) Taxation precedes spending. (Orthodox Economics)

It is wrong to be dogmatic about this non-issue and MMT advocates do themselves a disservice by insisting on it. This is provable in logical-philosophical terms. In a fiat money system, with money being a notional quantity not a real quantity, neither statement has any real objective content when it is removed (abstracted) from the real economy. The MMT argument is couched such that its corollary is that money must be created by the budget before it can be destroyed by taxation. I have seen noted MMT proponents give written expression to this form.

The Argument.

It is meaningless to claim that the following two statements have any real or functional difference in the case of a balanced government budget. (By extension of reasoning we can deal with unbalanced budgets.)

(A) You create money by expenditure and then destroy it by taxation.

(B) You tax existing money and then you spend existing money.

Mathematically the above equate to;

(A) +1 – 1 = 0

(B) -1 + 1 = 0

These mathematical statements are equivalent for notional quantities. Of course, they are not equivalent for real quantities, say cars.

With real quantities, you can do A from scratch:

Have zero cars, then create a car, then destroy a car and have zero cars remaining.

But you cannot do B from scratch:

Have zero cars, destroy a car, have minus one cars and then create a car and have zero cars remaining.

MMT seems to insist on A as the only real way of looking at the notional system. MMT proponents seem to think this makes some real difference to their overall case when it is at best a rhetorical device to get people to see that money (a notional quantity) can be created ex nihilo by “printing money”. Most intelligent, educated adults know this anyway.

MMT proponents use various examples to attempt to “prove” that the notional processes (A and B) are different. One example is year zero of new country. Let’s call the country New Pacifica which will fiat issue Nepacs as their currency. They say there is no currency to start with and that currency must be created before it is destroyed. In a notes and coin sense this might true for physical legal tender but in an accounting sense it is not true at all.

Let our example be essentially about ledger, balance sheet or electronic currency not physical notes and coin. Following the argument of MMT proponents, the Nepac must be created as budget spending and credited to accounts before people can pay taxes and thus allow the state to notionally destroy the currency again. However, in reality the Nepac only has to be created as a category with financial and legal reality by an enabling law of the parliament or ruler to be “notionally real”. No Nepacs have to be minted, printed, ledgered or accounted at this point. The Nepac is legally real, already legal tender by law. In fact it has to be real as legal tender in this category sense before a quantity of it, positive or negative, can be accounted. This is a very important point. MMT proponents fall for a kind of intermediate level of the fallacy of false or misplaced concreteness (reification). The intermediate level is thinking the currency is only notionally real when first accounted. But it is actually notionally real when legislated as legal tender. No quantity accounting of the unit does occur or can occur until the unit is legally real.

People could easily accrue tax obligations as negative values in their account or ledger before positive values are credited. That is to say, taxation could start before government spending. The New Pacifica government might decide (somewhat unwisely perhaps) to have a poll tax or a window tax and levy it up front at the start of each financial year. Thus they could levy this tax first in year zero and negatively credit every potential taxpayer’s account or ledger. Now New Pacifica has positive numbers on its government budget balance sheet and can start spending. My point is you could do it this way too. Taxation could precede spending. You can do it either way, it doesn’t matter.

The other artificial aspect of MMT’s year zero example is that there is never really a neat year zero in empirical reality. Before year zero, money or proto-money exists in some form before the creation of the new fiat currency. So, there is (or should be) for economic, social and equity reasons a conversion process. In New Pacifica, coconuts could have been a barter medium and thus a proto-currency. The government guarantees to change one cococut for 1 Nepac in a transition period. Thus you can eat your coconut, barter it or exchange it for 1 Nepac. But if you want to pay your 1 Nepac poll tax or window tax (to get your account back to zero) you must exchange 1 coconut for 1 Nepac at the State Bank then walk across the road to the New Pacifica Tax Office and pay 1 Nepac. (The government separates these sites for both administative and re-educational reasons. They want to re-educate the populace to use a fiat currency and separate it in their minds from barter.) Thus another part of MMT’s argument holds. You do have to hold the fiat currency to extinguish tax obligations.

In a way, in the transition process you are extinguishing your tax obligation with a coconut but in a two step process. It’s not so different from any currency transition where two currencies are legal tender for a while. In the long run though you must have Nepacs to extinguish tax obligations in New Pacifica.

MMT should drop the argument that the budget creates all the budget money and that later taxation destroys it. In the repeated annual circuit of finance such chicken and egg arguments about primacy in a notional system are pointless. They are even pointless in the year zero case as I demonstrated.

From Bill:

“A common misconception seen in the derivative literature on MMT (which is dominated these days by blogs, social media pages and tweets) seems to think that MMT says that currency-issuing governments are omnipotent and can solve any crisis just by spending. None of the main proponents of MMT over the last 2 decades has ever made statements to justify such a view.”

From the top of Warren Mosler’s blog page:

“Mosler’s Law: There is no financial crisis so deep that a sufficiently large tax cut or increase in public spending cannot deal with it”

Now to be fair, Warren did add tax cuts to the strategy, so it wasn’t just spending, and he did qualify it to be specific to financial crises, not arbitrary crises, but I think you can see how someone reading this could draw the conclusion that MMT proponents believe that currency-issuing governments can solve any financial problem by means of fiscal policy.

The nuances of language are tricky, as you demonstrate in your weekly quizzes. it’s easy to say something that seems precise and clear to you, but it easily misinterpreted by a reader. So sometimes when I perceive a difference in what various MMT authors are saying I am left wondering whether there is a real difference or just a difference of expression. I can imagine ways that I might modify or qualify either your statement or Warren’s or both to reconcile the two, but I’m not at all sure how YOU would do that and that’s what I would really be interested in understanding.

I owe a lot of what I know about macroeconomics to the MMT literature, but sometimes there appear to be pretty distinct differences between its various proponents. I was once rebuked on an MMT blog (by a major proponent) for saying something that was a more or less direct quote from another main MMT proponent. When I pointed that out, there was a terse backtrack, but never a resolution of the obvious difference of opinion between the two. I have no problem with differences of opinion, that’s part of what makes blogs interesting. But all in all I’m not sure that MMT is quite as unified a theory as you wish it was. You guys get attacked a lot, so I can see how it would be easy to adopt a sort of siege mentality and want to stand together against those attacks, but my own opinion is that it is ok to disagree once in a while without doing irreparable harm to the underlying basic ideas.

Ikonoclast

It seems to me the MMT people go on about it is because most of the public believe, because ‘taxation precedes spending’, that this is a real constraint on their government to provide public services and pursue full employment when, as you have demonstrated superbly, this is clearly not the case.

Don’t you think they need to know ?

Ikonoklast, Leonard Cohen has also seen the future, “and it is murder”. This may be a closer future than yours, which is so far distant as to be virtually irrelevant to our present discussion. That sectors of humanity are destroying more resources and animal an plant species than any other generation is certainly true and we can’t go on doing it.

A BBC commentator has reacted to Osborne’s autumn statement by saying that it will take the country back to the 1930s, adding the descriptive images of children without shoes, food banks, people without clothes or heating. This appears to have backfired on Osborne. Tory support has decreased significantly though not dramatically. The public is no longer with him on Draconian cuts, it would seem.

@Neil Wilson I think you have it exactly right and Professor Mitchell I think this is a great post.

Sure, Russia has a sovereign currency but did they use it to maximize the productive capacity of its own nation and people? No. Did they set up a system wherein they could absorb inflation in food imports? No. Did they do anything to make it so their economy was not a Petro-State? No.

The insight of MMT is that they could have used their sovereign currency power to create conditions that would not make them so vulnerable, in real terms, to something things like the rising prices of imported foods due to devaluation.

“People could easily accrue tax obligations as negative values in their account or ledger before positive values are credited.”

But is this how it operationally works in reality or is it your narrative on how one can choose to look at the operation giving the same end result, though it doesn’t operationally work that way?

If your narrative is describing the operation correct then MMT describes the operation incorrect. But then you need to show that it operationally works the way you describe it and not just that it is *possible* to operationally do it the way you describe it.

Ikonoklast, I regret to say that your pseudo-math example is a non-sequitur. It is not relevant to anything anyone, whether MMTer or not, would advocate. You are attempting to set up a Rawlsian Initial Position, a good thing to do, and argue from there. But then you branch off into irrelevancy.

I also did this, in this way.

Initial position: you have just created a gov’t with a legislature, a judiciary, an executive, and a treasury. Plus a central bank. There is an infinite amount of money.

Only the government treasury or the central bank is allowed to create or “print” money.

Question: how does anyone else obtain any money?

Answer: by the government spending it initially.

The money then circulates & recirculates in both the private and public sectors.

Money does not originate in the private sector in the economy we actually have. Government supplies it.

This hypothetical example is not intended to be historically accurate. And I equivocate between “currency” and “money”. Nevertheless, from the way in which I have set up the scenario, your “argument” can’t even get started. And I think badly misrepresents what Bill and others, like Randy Wray, are arguing.

Ikonoclast,

I should have added that once the Initial Position has been moved on from, then the monetary circuit is a balancing act between the private and public sectors. What that balance is to be is decided by political mechanisms possibly informed by economic data. I say possibly because Osborne’s autumn statement appeared to be devoid of “real” data. And the OBR and the IFS both disagreed with the conclusions he drew from his own, self-contradictory, presentation. Whether taxes or spending or both are used to deal with a serious deflationary situation wouls be a matter of judgment.

If one thinks it is a good idea to go back to the 1930s, or sterilize the working class in order to curtail what one conceives to be their excessive breeding as was once advocated by one of Thatcher’s advisers, then an empirically accurate economic theory should inform you the way to go. On the other hand, if one does not intend to destroy the public sector, as the British public apparently does not wish to see, an empirically accurate economic theory should, as before, show you the way. An empirically inaccurate economic theory, e.g., neoclassical economic theory, will not be useful in either scenario and will result in poor political decision-making at the very least.

Neil, while I agree with you about the manner in which you wish to set the discourse, I disagree with your use of “theoretical”. Instead, I would advocate the term, “hypothetical” in the case at hand. Let us take three hypothese, H1, H2, and H3. The first has not yet been empirically tested and thus still has the status of that of a hypothesis, which is “untested theoretical statement”. H2 has been tested and found to be false. H3 has been tested and found to be true. H2 and H3 can now be genuinely referred to as theories, though one is false and the other is true. H2 has no model while H3 does. A model is a non-linguistic structure in which a theory is true. Models can be conceptual or non-conceptual. A wind-tunnel is a model of air-flow dynamics and can serve as a test of a theory of how air flow moves with respect to the wings of an aircraft.

A true theory has a model. A false theory doesn’t. This distinction makes a nonsense of the way many scientists use the term, “model”. If you conflate “model” with “theory”, then you are unable to say that a given theory has a model, nor can you specify properties of the given model. It isn’t a model that is true or false. It is a theory. One might argue that this is merely a difference of semantics, but I would argue that this defense confuses the nature of semantic analysis, which relies on the difference between theories and models.

When you come to computer simulations and talk about computer models, the situation becomes increasingly confused and confusing. The question in the air is whether a computer program/simulation is a theory or a model. While I can’t definitively say whether such a program is one or the other, I think I can safely contend that it can’t be both. Also, it seems to be that conflating “theory” with “model” not only doesn’t help, it hinders the investigative process.

Ikonoclast

In the short run it appears the country of New Pacifica obviously has more food than coconuts,as to

during it’s transition period,where the state bank may well end up full of them,still without a Nepac put into circulation.

People would all default at the start of the fiscal year.

Larry,

I appreciate your feedback. I am attempting to understand some seemingly paradoxical things about money and economics. The first paradox has to do with money. Is it real or notional or does it in fact have several levels of “realness”? We can answer this question in various ways.

(a) Money is not real in the sense that the physical (matter-energy) is real. Under the Law of Conservation, updated to take into account mass-energy equivalence, mass-energy cannot be created ex nihilo (out of nothing) or destroyed in nihilum (into nothing). However, money can be created ex nihilo and destroyed in nihilum by fiat (let it be done). The “let it be done” is a legal decree by government, ruler or enacted law.

(b) Money is real in the sense that any social arrangement or convention is real. The word for young humans in English is “children”. In German the expression is “Kinder” or “Die Kinder” if the definite article is always required by German grammar. These words are real in their parent language and in the minds and behaviour (utterance and hearing) of native speakers but not real in the sense that real children are real.

If MMT (Modern Monetary Theory) is to advance an hypothesis or theory or model of modern money it must first define money. It must then define its “levels of realness” or “levels of abstraction” in the process of contrasting it and delineating it from real objects, real energies and the system of the real economy compared to the financial economy. It must do this last when it moves from description to prescription and wants to make statements delineating notional limits from real limits as Neil has illustrated. Of course, it is vitally important to delineate notional limits from real limits and all economics should be vitally concerned with this issue.

When I talk about “levels of realness” or “levels of abstraction” this is I believe a defendable concept. Value is most real when I am gaining utility from the value i.e a use value. Food has a use value. I use it or consume it to grow, repair, stay alive and enjoy life. Before I eat the food it has a potential value for me. Before I buy the food, my money has potential value (now called exchange value) to help me obtain food. If I have worked and am owed money it means I have a legal claim on the money but I don’t have it yet. It’s exchange value is now attenuated. A food shop that accepts my credit will give me food on credit but a shop that does not accept my credit will not give me food in exchange for any kind of IOU. Already, the exchange value is attenuated or “less real” in an objectifiable way. I could tell the shopkeeper that “I have speculated in derivatives and credit swaps and soon I will be rich. Then I will pay you double for this food.” The realness of my future money is now much more tenuous and the shopkeeper would almost certainly show me the door.

This argument about the degrees of realness of money (or capital when it morphs into capital) is entirely germane. Take this passage from Wikipedia about capital (following Marx).

“Fictitious capital is a concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy. It is introduced in chapter 29 of the third volume of Capital. Fictitious capital contrasts with what Marx calls “real capital”, which is capital actually invested in physical means of production and workers, and “money capital”, which is actual funds being held. The market value of fictitious capital assets (such as stocks and securities) varies according to the expected return or yield of those assets in the future, which is at best only indirectly related to the growth of real production. Effectively, fictitious capital represents “accumulated claims, legal titles, to future production” and more specifically claims to the income generated by that production.

Fictitious capital could be defined as a capitalisation on property ownership. Such ownership is (legally) real and legally enforced, as are the profits made from it, but the capital involved is fictitious; it is “money that is thrown into circulation as capital without any material basis in commodities or productive activity”.

Fictitious capital could also be defined as “tradeable paper claims to wealth”, although tangible assets may themselves under certain conditions also be vastly inflated in price. In terms of mainstream financial economics, fictitious capital is the net present value of future cash flows.”

Money and capital are slippery concepts and seem to cover a spectrum from the real to the notional. I return to my point. MMT needs to define money in all its forms in the modern monetary system. Maybe it has done so and I can be linked to a hopefully extensive and complete defintion. I suspect even then that different brands of Orthodox, Heterodox and Marxian economics (to name three broad categories) will have different definitions. Also, is it clear where money ends and capital starts? Are each valid category concepts and so on?

MMT is very descriptive. A broader and deeper question is this. If the economic system or even the financia/legal system fundamentally changes then does the current form of MMT become an historical artefact?

On the proposition that “it is vitally important to delineate notional limits from real limits and all economics should be vitally concerned with this issue,” MMT should note that the real economy flow is worker creates article then the article created can be appropriated and used by government. The real “taxing” flow goes in this direction. Insisting on a nominal flow the other way has little to recommend it as a concept. The citizens’ real efforts and real productions are taxed by the government in the real sense. This is the sense in which citizens understand taxation FROM THEIR VIEW. (Sorry I dont know how to underline). They see money as a proxy for this process.

One can look at it formally, that is notionally, either way. I still think I hold my argument on this is correct. I admit to doubts too now. The reason is one can play logical “games” with notional quantities that one cannot play with real quantities. My very argument could be used against me to say the notional flow description is correct because it does not have to conform to the real flow and it does describe what actually happens in current practice. So I am not being dogmatic about this… at least not yet.

However, the MMT notional flow argument does go against “common sense” or common opinion (which are not always to be trusted of course) and against the real flow of “taxing” real good and services as opposed to the nominal flows of accounting for it. Semantically, “taxing” can have two meanings here, namely “formal money taxing” or “taxing of real effort embodied in real goods and real services”. In the second sense, creation of the real good or real service has to occur before for goods or simultaneously for services before the government can “tax it” in that second sense. When an orthodox economist says “taxation must occur before government spending” we can read it as “real production must occur before real government consumption”.

“”A common misconception seen in the derivative literature on MMT (which is dominated these days by blogs, social media pages and tweets) seems to think that MMT says that currency-issuing governments are omnipotent and can solve any crisis just by spending. None of the main proponents of MMT over the last 2 decades has ever made statements to justify such a view.””

Agreed, and this was the main point I made in my post

Ikonoclast:

In regard to “common sense”, I am reminded of a statement made by Bertrand Russell:

” The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd. ”

And since you have introduced physics into the discussion, I would add that scientists are well accustomed to handling counter-intuitive concepts — notable examples being quantum mechanics and relativity theory.

Guantanamo along with a lot of other actions are part of the momentum of war. War is a profitable business for some. It destabilises communities and shifts control of assets. Weapons themselves make a lot of money. Torture, and other divisive actions like arming different people against each other are means to promote ongoing war.

Admitting to torture and other illegal actions seems to me to be a way to undo peoples’ faith in the rule of law and the agency of nations. Money can do what it wants. Some people also buy into it. Perhaps because the economics we use is exploitative and is based on inequality it is an extension of that devaluing of other people to participate in war, torture, broken human rights.

Dear Neil

The reason why so many people think in terms of financial resources instead of real resources is that such reasoning is usually valid at the household level. The more money a household has, the more resources it can acquire. This is true even when their is a food scarcity. As a rule, it isn’t the rich who starve. We are dealing with a fallacy of composition here. It works at the household level, so it should work at a higher level.

Suppose that there are 100 people in a room and also a table with 50 sandwiches. Each person has 5 dollars in his pocket and would like to buy a full sandwich. If there is a smooth market, a sandwich will cost 10 dollars and each person will get only half a sandwich. Now suppose that 20 of the 100 have 100 dollars in their pocket. They can now buy their full sandwich, but the other 80 will have to divide 30 sandwiches among, so each can get only 0.375 sandwich, and the price of a sandwich will rise to 13.33. Having more money worked for the 20 rich ones because they now can get their full sandwich.

Regards. James

Mr Quiggin

I guess i have to ask the question without expanding on an E-mail but,could you be so kind as to address the comments by Warren Ross & Senexx within regards to your interview front page at ‘MMM’ titled,

“Quiggin on MMT & Market Monetarism”.

No need to go bananas as some of the comments herehave today,maybe a little two speed oriented to 457 the narui frame,as we’d all like sometime to wrap the Xmas stockings…cheers ,and merry times to you and the real MMT crew..bill

Thanks

See my reply at #26 on the John Quiggin blog where I admit defeat in my attempted refutation. It turns on the issue of the system requiring a positive money supply. Either I am just plain wrong or I am attempting the refutation in the wrong manner. There are no other options. I will admit I have a lot of egg on my face at this stage. Maybe I should bow out and leave economics to trained economists. But when the trained economists differ widely and even diametrically on this and many other issues what does the concerned citizen but mere layperson in economic matters need to do to form his own opinion? He can read a lot of conflicting opinions. What then? He must, if stubborn and lumbering (about my only intellectual qualities) attempt to nut it out himself. Or I suppose he can leave such questions to his intellectual betters and simply suspend judgement.

iconoclast

to escape the notional chicken and egg

think power

always provides clarity

who wields fiat monetary power?

whose decree?

is it the sovereign currency or the subjects?

Dear John Quiggin,

you say in your comment above:

Saturday, December 20, 2014 at 12:06

“”A common misconception seen in the derivative literature on MMT (which is dominated these days by blogs, social media pages and tweets) seems to think that MMT says that currency-issuing governments are omnipotent and can solve any crisis just by spending. None of the main proponents of MMT over the last 2 decades has ever made statements to justify such a view.””

Agreed, and this was the main point I made in my post

but at http://johnquiggin.com/2014/12/18/mmt-and-russia/comment-page-2/

you seem to be saying that the following is your main point:

To sum up, while MMT provides a different and sometimes useful way of looking at the interaction between monetary and fiscal policy, it doesn’t change the basic equation that, in the long run, public expenditure is paid for by taxes

which in my reading is saying what the main point is in contradiction to what you claimed in your billyblog comment.

Take care

Graham Wrightson

In the following blog posting (May 9th, 2011) about his disagreements with MMT

http://johnquiggin.com/2011/05/09/some-propositions-for-chartalists-wonkish/

John Quiggin made the following propositions:

1. Except during the period since the GFC, money creation has not been an important source of finance for developed countries

2. Except under extreme conditions like those of the GFC, money creation cannot be used as a significant source of finance for public expenditure without giving rise to inflation and (if persisted with) hyperinflation

3. Government deficits must be financed primarily by the issue of public debt

4. The ratio of public debt to GDP cannot rise indefinitely, since governments will ultimately find it impossible to borrow

5. The larger the deficits governments want to run during deficits, the larger the surpluses they must run in booms

Proposition 2 – which once again raises the spectre of the inflation bogeyman – is obviously wrong (i.e. if money creation is denied as a source of finance for public expenditure, then there would be no regular increase in either the money supply or the supply of reserves, even in pre-GFC times ).

And proposition 5 seems to be saying that there needs to be a “long-run” balancing of deficits and surpluses. Clearly this is also wrong, because historical records over at least the past 100 years clearly demonstrate that federal budgets in both Australia and the U.S. have been in deficit for most of the time, while attempts to run surpluses have always been followed by recession.

Bill might like to consider doing a blog on these claims at some future time, if he has not done so already.

Ikonoclast

I to could have pulled names apart,but being time poor i chose to ponder the question and set the right of reply to non-applicable..with regard to Mr Quiggin, I must admit i was most impressed with the gentleman’s knowledge and explanations the last time i visited his blog..the subject at the time was to do with the affect and disparities between the import and export sectors with regard to the GST costings and disadvantages contained..as i said i think he’s well written and knowledgeable,as i see you are, however where as you seem struggle with theory i to question..he seems trapped to by theory without…not actual rate of unemployment information…now i am no fool and neither is he and you alike maybe just need do a little more debriefing 101..Cheers Merry Xmas

“If MMT (Modern Monetary Theory) is to advance an hypothesis or theory or model of modern money it must first define money. It must then define its “levels of realness” or “levels of abstraction” in the process of contrasting it and delineating it from real objects, real energies and the system of the real economy compared to the financial economy.”

Money is a product of law. Just like incarceration is a product of law. There’s no way to define it except to evaluate it’s reality at a given point in time. Both money and incarceration cannot be adequately “defined” without considering the real consequences that are experienced by every single “citizen” in addition to the consequences of the “state” (or other authority) charged with enforcement of the law. Money is what money does.

There is no “definition” of either term that will aid understanding without observation of reality. Even what is written in the “book of law” doesn’t really matter, because that doesn’t necessarily reflect reality. Imagine a student, completely ignorant of all human law and custom who wished to develop a theory of money and incarceration so that he might accurately predict the circumstances of a citizen in the United States in very specific circumstances. (Isn’t that the purpose of law anyway? To give each citizen who understands it enough knowledge to alter his behavior in certain ways in an attempt to achieve or avoid the consequences prescribed by the law.) That student may be interested in predicting, for example, what real consequences may be encountered by a citizen who chooses to speed with a broken tail-light, while possessing a certain amount of marijuana, through a certain town in a certain county in a certain state. Reading every statute on the books from the local to the national level won’t help our student develop a theory that can accurately predict what real incarceration this citizen will encounter. It may turn out to be 2 months, 2 decades or anywhere in between. If our student really wants to know how the “law” will affect those who encounter that particular circumstance, he would be better served by studying the real outcomes of others in that situation instead of relying on what he can learn about the “law” by reading it’s formal definition.

And so it is with money. Justice is not blind and neither is money. Money is a creation of law, but we should not be so naive as to think money IS ONLY what our laws say it is. Money, as it is experienced by a particular citizen is altered with each dollar the government spends and takes back in taxes. But knowing every detail of the Federal Reserve Act along with every bank regulation on the books doesn’t provide a “definition” of what money is at that point in time. Even if one can know ahead of time, to the penny, what next year’s federal budget deficit will be and what proportion will be spent on war, ss payments, bank bailouts, etc… one cannot define money in a way meaningful for any individual citizen.

We all recognize that the judge represents the law. Let us also recognize that the banker represents the law. He does the work, on behalf of the government and under its regulation, of deciding who gets money and at what price. Both parties act to define how the law “really works” for citizens, despite what may be written in the books.

Money is not some sub-atomic particle or physical force of the universe that has an innate reality that we just haven’t yet comprehended and expressed with math. It is just a tool that humans have adopted to help govern themselves. Specifically, to mobilize real private resources for the common good. In a free society we can make it serve our purpose as well (and as fairly) as incarceration or any other legal tool we wish to employ. Like any other law, we can define it and enforce it as we wish. But like any other law, the enforcement (or lack thereof) is just as important as it’s written definition.