I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

The UK recovery is a false dawn

A few weeks ago (October 1, 2014), I wrote in this blog – British economic growth shows that on-going deficits work – that the British Chancellor was overseeing an expanding fiscal deficit and public debt ratio, which despite the rhetoric to the contrary, was supporting growth and helping private households increase their saving ratio. The national accounts and public finance data could not support the claim that it was austerity in the UK that was promoting growth. But in drawing that conclusion, I certainly didn’t want to give the impression that the conduct of macroeconomic policy in the UK was appropriate. The point was that growth, albeit tepid, was occurring in the UK and it was not in an environment where the fiscal deficit was being cut. The fact is that the UK economy is in a parlous

state and such that the word recovery is a totally misleading descriptor for what is happening.

I have been examining labour productivity trends in various nations lately as part of some research I am undertaking.

The evolving relationship between labour productivity (how much output is produced per hour worked or person employed – these are different ways of thinking about it) and real wages (the purchasing power of the monetary wages that are paid to workers was one of the crucial leading indicators that allowed Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents to foreshadow the GFC long before the signs were more obvious.

I have written before about way the deviation of real wages from output per hour worked or labour productivity. The increasing gap between the two with real wages lagging behind labour productivity has been a characteristic of the neo-liberal era, as a result of concerted attacks on the capacity of workers to gain real wages growth (legislative, market-based – that is, persistent underutilisation of labour, and self-destruction by many unions).

In most advanced countries, the gap started opening around the 1980s and has led to a major redistribution of real national income towards profits without a commensurate surge in private sector investment in productive plant, equipment and buildings.

What happened to the gap between labour productivity and real wages? The gap represents the increased share of profits in national income profits.

The question then arises: if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth sustain itself, given that it relies on growth in spending?

This is especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the an increasing obsession with pursuing fiscal surpluses, which, generally, squeezed purchasing power in the private sector over the last two decades, at least.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the goods and services designed for current consumption produced were sold.

But in the neo-liberal period, capitalists have found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals that we have read about constantly over the last decade or so.

Goverment deregulation of the financial markets and a relaxation of oversight by the prudential authorities, all in the name of the self-regulating, free market myth provided the answer.

The rise of ‘financial engineering’ over this period as banks went wild in the deregulated environment pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector.

The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages.

The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing fiscal surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold. And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This is the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The bottom line is that there will be no sustained recovery and return to stability until real wages are allowed to grow in line with labour productivity growth.

This will require government action, the first step being to restore true full employment. A strong labour market makes it hard for employers to resist legitimate wage demands.

Money wages have to grow not only in line with the inflation rate but also in line with the productivity growth rate.

At present, economies are achieving growth with a mix of mini-jobs (Germany), zero hour contracts and fractionalised work (UK), part-time, precarious jobs (just about everywhere) and these labour market developments might suit capital but they undermine the capacity of workers to enjoy real wages growth.

Forcing employers to search for labour in a tight labour market is one of the essential criteria for recovery.

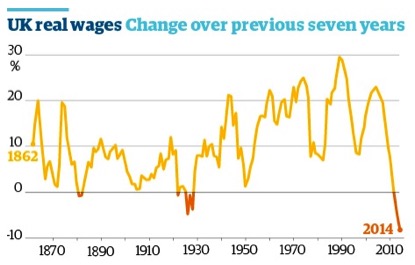

The UK Guardian article (October 19, 2014) – Bleak figures show a relentless slide towards a low-pay Britain produced this graph, which is scary in itself.

It shows rolling 7-year percentage changes in real wages going back to 1862. As the Guardian notes ” it is very rare for real wages in the UK to fall continually over a seven-year period. They have done so only three times in the past 150 years: after a deep recession in the late 19th century; in the 1930s, following the Great Depression; and again in the past seven years.”

The current period is looking very ominous in this regard.

So at this point we can conclude that workers in the UK are poorer in real terms with respect to the purchasing power equivalent of their wages. That is not what happens in a typical recovery. The reverses is the norm.

By the way, the Bank of England provides an excellent – Three Centuries of Data – for the UK, which you might want to file away for future use. It is a compilation of sources and very comprehensive.

The Guardian article suggests that the “most rapid growth in employment in recent years has been among professionals and technicians who possess the digital skills to exploit technological change” and “there has also been strong growth in the number of low-skilled, low-paid workers”.

It then asks why “why rapid growth in demand for high-skilled workers has seen their real wages rise over the past 20 years, while similar rapid growth in demand for low-skilled workers has been associated with real wage stagnation.”

The answer it gives is that the large pool of unskilled labour shed as the UK deindustrialises and jobs are replaced by technology means that there “are more people chasing every low-skilled job than every high-skilled one.”

However, the latest ONS data referred to above shows that in the higher-skilled sectors, real hourly earnings are falling faster than in other sectors. Of-course, shifts in occupational distributions within these industry sectors help explain the anomaly.

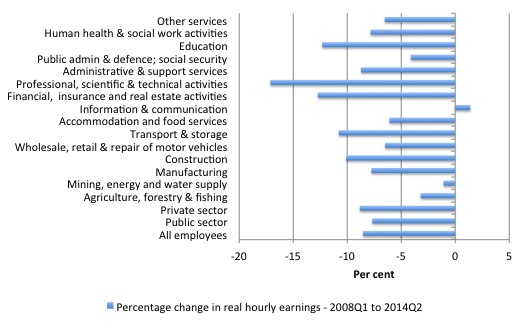

The next graph breaks the change in real hourly earnings in the UK by industry – from the peak in March-quarter 2008 to the June-quarter 2014 (percentage change over the period).

You can see that there has been no public sector leadership in this regard.

Total real hourly earnings have fallen by 8.5 per cent over this period. The largest falls are in the Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities (17.1 per cent cut), FIRE (12.7 per cent cut), and Education (12.3 per cent cut).

With the exception of FIRE, the other two sectors are closely related to productivity growth in the UK economy.

The UK Guardian article also brings our attention to the distributional movements within industries:

Even before the financial crisis, real wages for those on the lowest pay were rising less rapidly than for those at the top. As a consequence of the recent falls, for those in the bottom 20% of the earnings distribution, real pay is back to its 1997 level. Meanwhile, the top 10% have seen their real pay increase by about 20% over the same period.

In the June-quarter 2014, Average hourly earnings in the UK were £13.07 per hour. The lowest decile earned on average £6 per hour (that is, the bottom 10 per cent of the wages distribution), the lowest quartile £7 per hour (that is, the bottom 25 per cent of the wages distribution), the upper quartiles (top 25 per cent) £16 per hour and the top decile, £23 per hour.

That gap has actually fallen since the data was made available in the March-quarter 1997.

The 90/10 ratio (top 10 per cent over bottom) was 13/3 or 421 per cent in the March-quarter 1997 and in the June-quarter 2014 it was 23/6 or 394.3 per cent.

Since March-quarter 2008 (the peak quarter in the UK before the GFC), the 90/10 ratio for hourly earnings was 21/5 or 396 per cent.

So it is hard to square the Guardian’s calculation with respect to real hourly earnings of employees. Of-course, total earnings are broader than the wages earned by employees and that is the difference.

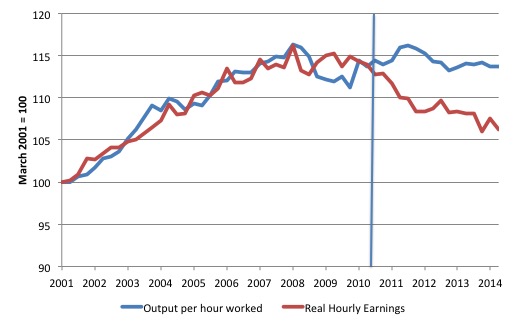

And now we introduce productivity into the analysis and the following graph should frighten you. It shows the growth in labour productivity (real output per hour) for the UK economy, indexed at 100 in the March-quarter 2001 and the growth in real hourly earnings over the same period.

Please not that the way two time series behave when indexed is, in no small part, due to when the base year is imposed. If I had constructed these indexes with the base year of 100 further back in history, you would have observed a wider gap between the series.

The vertical blue line is when the current British government assumed office in May 2010.

I am interested in this blog in looking at what happened since the last peak – where the British economy posted 5 successive quarters of negative growth from the December-quarter 2008 and the economy has grown by 2.6 per cent in total since the last real GDP peak (March-quarter 2008) – that is, in 6.25 years it has barely grown at all.

Labour productivity per hour is 2.2 per cent below the March peak, while real wages are 8.5 per cent lower.

Neither dynamic reflects a strong economy in a full scale recovery. The declining productivity growth is bad enough but the rising gap between the two time series means that the dynamic that was in place prior to the crisis is getting worse.

The theme of a poor recovery is taken up by the Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang in the UK Guardian this morning (October 20, 2014) – Why did Britain’s political class buy into the Tories’ economic fairytale?.

He presents a progressive edge to the debate but if you read his article carefully you will see that he falls into some of the classic neo-liberal myths about fiscal deficits, which undermine the power of his argument.

In effect, his argument could easily be turned back on him in other circumstances given his errors.

His basic argument is correct – the British people have been conned by a conservative myth that – the current Government is engaged in a repair job after the mess left by the previous Labour regime.

In that context, the task of government is to reduce the fiscal deficit and to allow “people to stand on their own feet rather than relying on state handouts.”

He correctly notes that:

Even the Labour party has come to subscribe to this narrative and tried to match, if not outdo, the Conservatives in pledging continued austerity. The trouble is that when you hold it up to the light this narrative is so full of holes it looks like a piece of Swiss cheese.

He then determines that the rise in the fiscal deficit “was mostly a consequence of the recession caused by the financial crisis” as tax revenue fell and income support payments rose.

That is, one could not conclude that it was due to “Labour’s economic mismanagement”. In fact, from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective there was economic mismanagement by Labour but not the type he is referring to – an excess of net spending.

The mismanagement occurred because the Labour Government didn’t expand the fiscal deficit enough. Ha-Joon Chang’s argument that the rise in the deficit was all down to the automatic stabilisers – that is, the cyclical sensitivity of the fiscal balance – suggests that the Labour government did very little in a discretionary sense to combat the GFC.

It started to rehearse the deficit-public debt is bad mantra in the lead up to the 2010 election and as a result unemployment rose unnecessarily.

But that is an aside to the point I am making here.

Ha-Joon Chang argues that the Tory argument about the dangers of public debt reflect a:

… pre-modern, quasi-religious view of debt. Whether debt is a bad thing or not depends on what the money is used for.

He then uses a private sector analogy to make his point and claims the “same reasoning should be applied to government debt”, which is the classic error that progressives make when considering public and private debt comparisons.

First, we are talking about a currency-issuing national government here, which provides the currency that the non-government sector uses.

Remember, a sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.

The Guardian author doesn’t seem to comprehend that.

Second, within that context, all public debt is unnecessary and essentially amounts to corporate welfare.

Third, there can be bad public debt. When? When governments think they have to issue debt in order to spend and then make outlays that do not advance public purpose (welfare). That sort of spending is wasteful.

Fourth, the claim that good public debt is when the government can afford to pay it back and is used to create longer run gains is erroneous in the extreme.

Ha-Joon Chang claims that:

For example, when private sector demand collapses, as in the 2008 crisis, the government “living beyond its means” in the short run may actually reduce public debt faster in the long run, by speeding up economic recovery and thereby more quickly raising tax revenues and lowering social spending. If the increased government debt is accounted for by spending on projects that raise productivity – infrastructure, R&D, training and early learning programmes for disadvantaged children – the reduction in public debt in the long run will be even larger.

The use of the term “living beyond its means” is neo-liberal framing. What are the means of the currency-issuing government? The answer has nothing to do with how much ‘money’ it has available.

The answer is the available real resources that the government can bring back into productive use via its currency monopoly.

From a financial perspective, the currency-issuing government has unlimited dollars (or pounds). There are no ‘means’ relevant.

From a real resource perspective, the limits are full employment and environmental sustainability.

In that case, if the projects to raise productivity are viable (that is, there are real resources available) then there is never a question that the government should spend the cash to make these projects happen.

Whether it has a large debt holding or none is irrelevant..

The link between the virtuosity of public debt and these expenditures is deeply flawed and plays right into the hands of the neo-liberals.

Progressive politics will always flounder if the parties take advice from this sort of reasoning.

Conclusion

Ha-Joon Chang is correct that the ‘recovery’ in the UK is a false dawn given the per capita income is still below the peak before the crisis and real wages are falling.

He is also correct to note that labour underutilisation is shifting in composition from unemployment to underemployed, precarious, low-paid, jobs, with an “extraordinary increase in self-employment”.

He is also correct that the ” success of the Conservative economic narrative has allowed the coalition to pursue a destructive and unfair economic strategy, which has generated only a bogus recovery largely based on government-fuelled asset bubbles in real estate and finance, with stagnant productivity, falling wages, millions of people in precarious jobs, and savage welfare cuts.”

But his reasoning for the success of the narrative is deeply flawed and one of the reasons why such a destructive lie has been accepted by the public.

With friends like that ….!

That is enough for today!

I was very disappointed with Ha-Joon Chang’s article.

I really thought he was better informed.

As to the productivity numbers, I can’t help feeling there is a measurement issue here.

I can’t prove it but the decline in real labour productivity growth combined with dramatic increases in official employment figures with low real GDP growth strikes me as suspicious but no one else seems to be making this point so I may be well barking up the wrong tree.

Letter published in Toronto Star (Canada’s largest circulation daily)

with unpublished footnotes also sent to editor:

High unemployment not inevitable

http://www.thestar.com/opinion/letters_to_the_editors/2014/10/16/high_unemployment_not_inevitable.html

Re: Balancing the books isn’t black and white, Editorial, Oct 13, 2014

http://www.pressdisplay.com/pressdisplay/viewer.aspx

Your editorial notes that a balanced budget may not be good news if it is achieved by cutting vital programs, overcharging EI premiums, or selling public assets for only short-term gain. It is also bad news if it means 1.3 million Canadians continue to suffer needless unemployment. Once the private sector has made its spending decisions, the government must either contain inflation by higher taxation if demand is too high, or conversely inject more funds into the economy through infrastructure spending and direct job creation if total demand is too low (as is the case today).

Since we have a sovereign Canadian dollar, the government is never constrained from spending whatever the economy needs to achieve full employment with price stability at any given time. The Bank of Canada can always create and lend monies to the federal government at low interest rates just as it did during WWII and through to the 1970s before neo-liberal economic thought took over for the benefit of corporate and financial elites.

A balanced budget with high unemployment is simply the ideological choice of those who prefer a submissive labour force, unwilling to fight for its proper share of productivity gains through increased wages.

Footnotes:

1. Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory … macroeconomic reality

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=28716

There is no reason that a fiscal balance should be anything in particular over any particular time period. It should be whatever is necessary to support the non-government spending and saving decisions and ensure there is sufficient spending in the economy to achieve full employment.

If that requires continuous fiscal deficits of 10 per cent of GDP then so be it. It is required permanent surpluses of 10 per cent of GDP then so be it.

For a nation with a very large external surplus (say a large energy exporter) and strong private saving, then a fiscal surplus might be appropriate.

But most nations will have external deficits of varying magnitudes and then if the non-government domestic sector desires to save, the public balance has to be in deficit, or else a recession will ensue.

2. Abba Lerner: Functional Finance

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=5762

The central idea is that government fiscal policy, its spending and taxing, its borrowing and repayment of loans, its issue of new money and its withdrawal of money, shall all be undertaken with an eye only to the results of these actions on the economy and not to any established traditional doctrine about what is sound and what is unsound. This principle of judging only by effects has been applied in many other fields of human activity, where it is known as the method of science opposed to scholasticism. The principle of judging fiscal measures by the way they work or function in the economy we may call Functional Finance … Government should adjust its rates of expenditure and taxation such that total spending in the economy is neither more nor less than that which is sufficient to purchase the full employment level of output at current prices. If this means there is a deficit, greater borrowing, “printing money,” etc., then these things in themselves are neither good nor bad, they are simply the means to the desired ends of full employment and price stability …

3. Almost Everyone’s Guide to Economics

John Kenneth Galbraith, Nicole Salinger

Bantam Books 1978 Page 92

“If there is idle capacity and unemployment, the government must spend more that it receives in taxes………there is no merit at all in a policy that just balances income and outgo, none whatever.”

I’m a bit puzzled by your narrative on the UK, but maybe I didn’t pay enough attention.

You used to say that Britain’s sluggish economy was due to austerity, and that you cannot know the government stance just by looking at public deficits, because deficits can grow in spite/because of austerity. But when Britain started growing again, you pointed to public deficits as evidence of the relative lack of austerity. Am I missing something?

Thanks,

Alex

Hey Alex, i might not have read your comment very carefully, but short answer is yes, you have missed something. You cannot know a governments hypocritical stance by looking only at one sector of the economy, to the exclusion of others. Never do I remember the author of this blog ever claiming the government as sole cause of the sluggish economy. But I too am a sloppy reader who could be wrong.

I can’t for the life of me see how British labour is productive., its a service economy.

If I am correct in my understanding of British labour activity as only a means to access purchasing power then any real rise in British labour rates will merely increase prices of goods over and above the ability to purchase them.

Causing a even bigger collapse of the production , distribution and consumption chain.

Again the core problem is the distribution of capital and therefore how it is used ( its not effective)

A BMW in each driveway rather then a 2cv ??

Although the Uk (unlike other euro countries) is receiving free goods from German and other european entrepots it cannot afford to use them (oil inputs wasted driving around in circles better used elsewhere)…….

Also immigration is a factor.

if you have a static to slightly falling total energy consumption and a rising population fleeing war zones that UK capitalists have created so as to maintain profits…………….what happens ?

Its simple physics is it not ?

Hi Willy,

Thanks for your answer, but it is not very helpful.

I do think (although I’m not 100% sure, that’s why I’m asking) that Bill said that austerity was one of the factors explaining Britain’s stagnant economy. But then in “Pre-crisis dynamics building again in Britain”, Bill writes that “austerity hasn’t been as severe at the macroeconomic level as the rhetoric might have indicated”, which explains the not-so-bad current growth figures.

I’ve got the impression that, in this particular case, Bill argues “A” and “non-A” successively. Again, I could be mistaken, but a sneering reply doesn’t address my question.

Alex

In the BoE spreadsheet, on the Trade Data page, in order to read all of the doumentation in column H, you will have to enlarge that row. Thsi operation can be carried out via the row number “column”.

“You used to say that Britain’s sluggish economy was due to austerity…”

“when Britain started growing again…”

Austerity does not imply NO spending, it means slower GROWTH in spending.

Thus we can have economic growth and still have austerity if spending growth isn’t high enough to fully utilize resources (labor). If the public deficit occurs under conditions of relatively high payments resulting from the automatic stabilizers, I would think this would be another indication of an austerity condition.

Economies are dynamic (growing) not static (non-growing) systems. In growing systems it’s relative numbers that inform rather than absolutes.

Andy, maybe I expect too much, but I have never been overly impressed with Chang.

larry,

“Andy, maybe I expect too much, but I have never been overly impressed with Chang.”

Even Krugman recently said that that a government cannot run out of its own money.

Paulmeli,

This doesn’t answer my question either. I am aware that you can have austerity and big deficits, austerity and no deficits at all, austerity and growth, austerity without growth, etc., but that’s not the point.

I’m just saying it seems to me that Bill blamed Britain’s disappointing results since the onset of the crisis on austerity, before asserting that today’s (relative) improvement is partly due to the fact that austerity wasn’t that stringent after all.

Thanks,

Alex

There definitely was austerity in the UK in 2011. If I remember correctly there were public sector cuts (net of tax) of about £8.8bn, with an extra £10bn raised by increasing VAT to 20% (raising price inflation to 5% in the process).

This had knock-on effects into 2012, but in desperation Osbourne raised benefits inline with inflation (5%) which, given the high multiplier associated with benefits, restored some growth. And the Payment Protection Insurance (PPI) refunds added about £15bn to consumption during 2011,12,13.

In other words, Osbourne back-tracked a fair bit without actually admitting it, and together with the population growth and PPI refunds has generated some temporary higher GDP growth. He got lucky in other words.

Hi Charles,

Thanks for your reply, which does address my question!

Alex

Another source of growth for the UK economy has been what we might call “beggar thy neighbour” growth, caused by lowering corporation tax (to 20% by 2015). This might add to UK growth as companies choose the UK to establish themselves, but it is happening at the expense of other countries, and so adds nothing to global growth.

From about 2012 onwards (after the disastrous 2011 budget), many of the cuts to public spending have been offset by tax breaks for business. In other words, Osbourne probably learned that if he wants a smaller state, it is not about just cutting public spending, but passing this on to the private sector.

Deficit reduction is now just rhetoric used to get elected.

a little harsh on Chang one of the better economic commentators reaching

a reasonable amount of people .He does not confront the myth of a financially

constrained state head on but he certainly has never suggested the government

can run out of money.

I have never believed there was a risk of economic collapse but I am having doubts.

It does seem as if a perfect storm is brewing.Globalization and the free movement of capital,

entrenched and increasing external deficits for much of the developed world simultaneous to

a political consensus on pursuing “balanced budgets” or in the uk both major political

parties promising government sector surpluses .

The inevitable resulting private sector deficits effects on aggregate demand will be magnified

by increasing inequality.Economic fear may well perversely drive people politically to the right.

What if an ideologically driven Republican Party captures US government and the two largest

economies the US and the eurozone both pursue austerity.We have had no more meaningful

oversight of the financial sector global financial crisis redux is always a threat.

The new right seem far less pragmatic than the old their faith in the invisible hand seems unshakeable

oh the irony capitalism laid low because neo liberals who actually believe the myths win political

power

very good point Charles J the effect of the PPI 15 billion stimulus was as crucial as

Osbourne’s pragmatic austerity lite conversion

“I can’t prove it but the decline in real labour productivity growth combined with dramatic increases in official employment figures with low real GDP growth strikes me as suspicious but no one else seems to be making this point so I may be well barking up the wrong tree.”

It’s the Oil industry that’s proving a bit of a drag. The relevant section is in the October Economic review. I find it quite persuasive.

Neil

Thanks for that. I guess I need to dig deeper to get a better feel for the numbers.

I would say Ha-Joon Chang knows the phrase “living beyond its means” is nonsense when applied to a sovereign currency issuing government like the UK which is why the phrase is given quotes.

In economics, like all academic disciplines, there will be career advantages in not veering too far away from the bounds of the “groupthink”. There’s enough in what Prof Chang has written to show he must understand MMT, although I can’t find any reference to show he’s expressed any opinion one way or another.

So hopefully that might change. It needs to change. We really need to get people like Prof Chang on board if MMT is going to break through from the periphery.

Overseas visitors to Ireland has recovered beyond 2008 levels except for UK residents.

http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=TMQ10

(select all & graph)

This is I am afraid how Ireland collects tokens.

A vast amount of kerosene is required – UK residents still seem to be unable to afford the kerosene required to fly from London to Dublin.

I think the data confirms that Osborne, at first, ‘got it wrong’, but then had a little luck and changed policy.

“But, on the same basis, the recent recovery has actually been slightly faster than during Thatcher’s hey-day.”

Due to G.B. quickly implemented stimulus package?

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/fin…

His austerity package was not expected to slow down/reduce the increase in GDP. He was hoping that monetary policy, supply side measures and the so called ‘Barro/Ricardo equivalence would lead to an increase in private sector demand.

When his policy measures ‘did not work’. He ‘changed tack’. He increased public sector gross investment. {A Keynesian stimulus?}.

In 2012-13 public sector gross investment was £17.78b. In 2013-4 public sector gross investment was £46.1b – an 159% increase.

He also had a little luck?

“One economist, Alan Clarke at Scotiabank, says the compensation payments have been more successful at stimulating the U.K. economy than quantitative easing. U.K. lenders have already paid £11.5 billion ($18.7 billion) to millions of customers, and have set aside another £7.3 billion for future

payments.

But the payments are not just creating one-off windfalls: the PPI industry is also creating much-needed employment.

As we report over on WSJ.com, claims have been coming in at such a clip that it’s created tens of thousands of new jobs to handle them.”

http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat…

Plus a government generated boost to the housing market?

“Even Britain has now abandoned austerity

And while Osborne will never publicly admit this, the big surprise of his budget is its implicit acceptance of this Keynesian view.

Instead of trying to reduce borrowing any further or aiming for a balanced budget, as it originally promised, the British government has now accepted that deficits will keep rising in absolute terms and will still be worth 6% of GDP by the next election in 2015. That would leave Britain with by far the highest deficit ratio among the major economies after five years of unprecedented austerity. Meanwhile the U.S., with comparatively little fiscal effort, is projected to reduce its deficit to just 2.4% by 2015.

We are still looking at borrowing of £108 billion this year – nearly £50 billion more than planned back in 2010.”

http://blogs.reuters.com/anatole-kaletsky/2013/03/21/even-britain-has-now-abandoned-austerity/