The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Austerity does not necessarily require a cut in government spending

The Bloomberg Op Ed article (August 19, 2014) – European Austerity Is a Myth – is about as flaky as it gets. The author is intent on justifying the article title by examining changes in government spending (as a per cent of GDP). He produces what he claims is “more appropriately called the ‘graph of the decade'”, which would mean it was some graph, but in reality tells us very little and does not provide the basis for his conclusion that rising government spending since 2007 is evidence that austerity has not been imposed. Oh dear! Some points need to be made.

The so-called – graph of the decade – was produced by Eurostat and appeared in the European Commission paper – Public Spending Reviews: design, conduct, implementation – produced by the Ecofin Committee.

You can also read a – Summary for non-specialists.

The graph shows the levels of government spending as a per cent of GDP for European nations in 2007 and 2013, and surprise surprise, the 2013 levels are higher in all but four nations (Bulgaria, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania). The Ecofin commentary says that:

The picture varies across the EU, reflecting national preferences and political decisions. In six Member States, public spending accounts for more than 54% of GDP, while in another six, the proportion is between 34% and 39%.

In the EU as a whole, the public expenditure-to-GDP ratio increased by 3.5 percentage points between 2007, the year preceding the crisis, and 2013. Four Member States, however, have managed to stabilize or even reduce their expenditure-to-GDP ratios over that period.

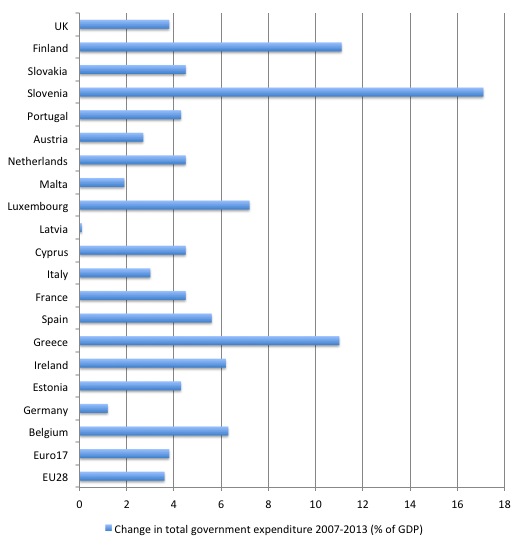

I produced the following version of the graph which just shows the change in nominal public spending as a proportion of GDP between 2007 and 2013 using the Eurostat data.

Okay, the evidence is clear. Government spending as a proportion of GDP in most nations rose during the crisis. The Bloomberg author claims that the total public spending in the EU initally rose (he uses the emotive word “ballooned”) and then “shrank a little”.

The conclusion about the shrinkage:

That, however, was not the result of government’s austerity efforts: Rather, the spending didn’t go down as much as the economies collapsed, and then didn’t grow in line with the modest rebound. In Italy, for example, the government spent 47.6 percent of GDP in 2007 and 50.6 percent of GDP in 2013, when economic output was 2.6 percent lower than in 2007. The country’s economy dipped into recessions, surfaced, struggled — but the government spent more or less as much money as before.

So he is just pointing out the obvious that the measure the graph focuses on is a ratio with spending as the numerator and GDP as the denominator. A ratio can move as a result of both components changing and so without firm knowledge of the components it is difficult to make unambiguous interpretations.

Given the collapse of GDP in many countries, the ratio will rise. For example, total public spending in Greece rose by 0.5 million euros between 2007 and 2013 (and fell substantially in real terms) but the nominal GDP fell by around 18.5 per cent over the same period, which accounts for the rise in the ratio.

Would anyone not conclude that Greece had undergone a dramatic austerity program even though government spending did not fall?

The point the Bloomberg author really wants to make is that public spending is in his view wasteful. He cites an example he copied from the Economist Magazine:

The ushers at the Italian Parliament, whose job is to carry messages in their imposing gold-braided uniforms, made $181,590 a year by the time they retired, but will only make as much as $140,000 after Renzi’s courageous cut. If you wonder what on earth could be wrong with getting rid of them altogether and just using e-mail, you just don’t get European public expenditure. It’s about preserving old inefficiencies as venerable traditions.

Its also about buttressing total spending. Using E-mail will probably save outlays, but what will happen to the economy as that spending and the multiplied effects once the worker spends his/her wages are lost? What will take its place?

Will Italian firms invest more to make up the difference when total spending and sales are in decline, just because the Italian Parliament is more “efficient”?

That is the macroeconomics issue that this author ignores.

He cites cases on senior Italian government officials earning “12 times the national average salary” as evidence there is “plenty of room for cuts in European bureaucracies”. I note he doesn’t mention the pay of private management elites relative to average wages.

I don’t seek to justify the wages of the senior managers. But apart from equity issues, the macroeconomic question is still relevant. If you cut that spending source what will replace it?

On the equity issue, it might be justified in hacking into executive pay. After all, the neo-liberal era has accelerated income inequality and driven a massive gap between the earnings of the lower and middle income earners and the top-end-of-town.

The largesse, by the way, came from the massive redistribution of national income towards profits as real wages growth lagged behind productivity growth.

But the problem is not confined to the public sector and cannot be used to argue that the public sector has a monopoly on waste.

In 2013 in Australia, for example, it was reported that the “bosses of Australia’s leading companies” were “taking homealmost 70 times the national average salary” and the “10-year trend, however, is much more stark, with executive fixed pay increasing almost three times as fast as inflation since 2002, and nearly 70 per cent faster than average wages growth”.

So perhaps we attack all executive salaries – public and private. The loss of total spending would be smaller than if we attacked the salaries of lower income workers because the higher income groups save more per dollar/euro.

But if total spending is inadequate (to achieve full employment) then something has to replace the specific, targetted cuts that are made.

The Bloomberg authors gets to his point with this conclusion:

There is no rational justification for European governments to insist on higher spending levels than in 2007. The post-crisis years have shown that in Italy, and in the EU was a whole, increased reliance on government spending drives up sovereign debt but doesn’t result in commensurate growth. The idea of a fiscal multiplier of more than one — every euro spent by the government coming back as a euro plus change in growth — obviously has not worked.

And then goes into a rave about “increased government interference in the economy” and that governments spending is not helping the recovery.

Who gave this guy a job?

First, the fact that government spending as a proportion of GDP has risen but economic growth still lags is not evidence that the spending multiplier has failed. The point this author ignores is that other things are not equal.

The true test of whether the expenditure multiplier is less than or greater than one is to examine what happens to economic growth (real GDP) if government spending rises while all other expenditure (non-government) is constant.

The point he ignores is that all spending – government or non-government – multiplies through the expenditure stream to create final growth outcomes.

If we assume for simplicity that the multiplier is similar for government and non-government spending and non-government spending is falling by more than government spending is rising, then we would expect to see overall output growth declining even though every dollar of government spending might be generating, say, 1.5 times the change in total spending.

Its just that the greater decline in non-government spending is also multiplying to a decline in total spending. The net result – decline.

Second, even if government spending is increasing in absolute terms, relative to GDP, or relative to its revenue, we cannot conclude that the fiscal stance of the government is not one of austerity.

Austerity doesn’t necessarily mean that government spending is declining. It has to be seen in context of what the other components of spending are doing and what is required in that context to keep growth growing at, say, its previous trend.

The fiscal deficit might be rising but we would still conclude that there is austerity if the net decrease in private spending, for example, has not been more than offset by the rising in the deficit.

Austerity is about the functional role of fiscal policy and merely focusing on government spending.

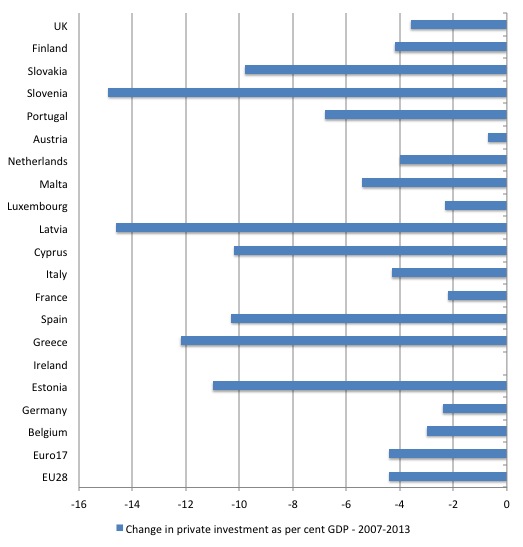

The following graph shows what happened to private gross capital formation (investment) between 2007 and 2013. What would the author conclude about that?

If government spending had not risen, given the collapse in private investment, what do you suppose might have happened to overall growth?

Further, when you examine the total expenditure mix (consumption, government, private investment and net exports), very few nations experienced a rise in total expenditure as a proportion of GDP between 2007 and 2013.

Conclusion

Given unemployment rose dramatically in most nations, the obvious conclusion is that the rise in government spending was insufficient and thus the policy makers have deliberately imposed austerity on their nations.

This article is just another in a long line of denials and is more overt than others that at least understand how to use the statistical concepts more reasonably.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It always amuses me that the mainstream seek to eliminate money from their models, but talk exclusively in money terms when it comes to resource allocation.

For *any* public sector job in existence, the first question is what is that person going to do instead. Who else is out there with an open cheque book and employment/training contract in hand ready to engage the individual. And who says that use of the person is better than what they are doing now.

Here in the UK there is constant talk that we can’t afford the NHS and yet nobody talks about what the people engaged in the NHS are going to do instead, and why that is a better use of their output capacity than what they are currently doing.

Its obviously true that government spending, and taxation, receipts cannot be considered in isolation. Yet time after time supposedly highly educated politicians and technocrats seem surprised that a reduction in spending isn’t matched on a 1:1 basis by a reduction in the public deficit. In fact it may make very little difference to the deficit but a great deal of difference to GDP which is probably what is happening in the EU.

Is their any studies of how long money spent by government actually stays in the economy, on average? For example, about 30% of money spent on salaries would come straight back as income tax. Then as the remainder of those salaries are spent, and respent, there would be a whole range of taxes levied at each transaction. After three or four re-spendings there would be hardly anything left. I would guess that this would be a matter of a few months at most. Maybe issued money has a half-life of around 2 months?

Looked at like that, it must be obvious, even to classically trained economists, that reducing government spending can’t possibly have a big effect on the deficit, but it can have a huge impact on GDP.

That summary for the non-specialist is one of the greatest oxymoronic titles I have seen in a long time. An English speaker who can’t write intelligible English. It reminds me of the messages I used to receive through the mail soon after I arrived in England many years ago telling me about programs that I could take advantage of. They were all written in English but not English as you and I know it. I couldn’t understand a word. I took a couple of them to colleagues and asked them if they could decipher the things. They couldn’t either and took the view that they weren’t meant to be understood. I think the same applies to the this document. While superficially directed to the non-specialist, the organization doesn’t really expect anyone to understand it. And what is the downside to the organization if they don’t? There isn’t any. From a neoclassical perspective, it is obviously the reader’s fault that this “gracious” attempt at communication fails.

Bill,

I notice hat in section 7 they show “case studies” of spending reviews conducted by the UK, the Nethelands and Ireland. In the case of the UK they show only what “savings” where expected, yet no analysis of whether the government actually delivered them. What’s the point of a “case study” without anayising its real outcome.

A comment on a previous thread lead me to crystallise my thoughts about the economic project I would wish to see happen.

I would like to see an explicit multi-disciplinary approach which considers “soft” (fiscal) and “hard” (resource availability) constraints together in a comprehensive economic approach. I would like to see the ultimate need for a renewable, circular economy acknowledged and addressed. I would like to see explicit admission that population/material/infrastructure growth (quantitative growth) cannot continue indefinitely on a finite planet. This is while accepting and advocating that qualitative growth (knowledge, technology, sciences, arts, education and human services improvements) can continue for a very long time.

I also want to see acknowledgement and exploration of the political economy dimension, specifically addressing the problems of monopoly capital and oligarchic control of our society. I do not consder a society democratic until workers own and manage enterprises under worker cooperative socialism. What we currently have is corporate-oligarchic command economy. That is why so many bad and biosphere-destroying decisions are being made.

I guess MMT is one tool in the toolkit. But someone or maybe some group needs to go further with an interdisciplinary approach drawing up to four strands together; these strands being formal MMT macroeconomics, renewable and circular economy approaches, biophysical economics and worker cooperative socialism.

On the fourth point, a society is not democratic just because it has democratic elections every 3 or 4 years and then a bourgeois parliament clearly in thrall to oligarchic interests. A society is not made democratic (as some argue) by having the “democracy of the market” where people “vote” with their money. In the market some people have a lot more “votes than other people. A society can only be truly democratic when the workplace is democratic.

Work defines most adults under our system and it is where they spend a huge part of their time. What is most workers’ current experience of the workplace? It is the experience of working under an autocrat, under the boss (or bosses). What is a corporation or even a small business in this context? It is an autocracy ruled by the owner(s) and their hired CEOs and upper managers. When so much of everyday life in our society is lived under these autocracies how can such a society be called democratic? It certainly is not democratic.

As alluded to above, even our bourgeois parliament does not enact the will of the people. It enacts the will of the oligarchs. It is clear that our major parties (Liberal and Labor in Australia, Republican and Democrat in the US) are but two wings of one super-party of capitalist oligarchy. They take contributions from the capitalists and make policy to suit the capitalists. In the US a study has proven scientifically (by analysing whose policy wishes are implemented) that the US is an oligarchy.

Here is the link to one report about it;

http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2014/apr/21/americas-oligarchy-not-democracy-or-republic-unive/

A comment on a previous thread led me to crystallise my thoughts about the economic project I would wish to see happen.

I would like to see an explicit multi-disciplinary approach which considers “soft” (fiscal) and “hard” (resource availability) constraints together in a comprehensive economic approach. I would like to see the ultimate need for a renewable, circular economy acknowledged and addressed. I would like to see explicit admission that population/material/infrastructure growth (quantitative growth) cannot continue indefinitely on a finite planet. This is while accepting and advocating that qualitative growth (knowledge, technology, sciences, arts, education and human services improvements) can continue for a very long time.

I also want to see acknowledgement and exploration of the political economy dimension, specifically addressing the problems of monopoly capital and oligarchic control of our society. I do not consder a society democratic until workers own and manage enterprises under worker cooperative socialism. What we currently have is corporate-oligarchic command economy. That is why so many bad and biosphere-destroying decisions are being made.

I guess MMT is one tool in the toolkit. But someone or maybe some group needs to go further with an interdisciplinary approach drawing up to four strands together; these strands being formal MMT macroeconomics, renewable and circular economy approaches, biophysical economics and worker cooperative socialism.

On the fourth point, a society is not democratic just because it has democratic elections every 3 or 4 years and then a bourgeois parliament clearly in thrall to oligarchic interests. A society is not made democratic (as some argue) by having the “democracy of the market” where people “vote” with their money. In the market some people have a lot more “votes than other people. A society can only be truly democratic when the workplace is democratic.

Work defines most adults under our system and it is where they spend a huge part of their time. What is most workers’ current experience of the workplace? It is the experience of working under an autocrat, under the boss (or bosses). What is a corporation or even a small business in this context? It is an autocracy ruled by the owner(s) and their hired CEOs and upper managers. When so much of everyday life in our society is lived under these autocracies how can such a society be called democratic? It certainly is not democratic.

As alluded to above, even our bourgeois parliament does not enact the will of the people. It enacts the will of the oligarchs. It is clear that our major parties (Liberal and Labor in Australia, Republican and Democrat in the US) are but two wings of one super-party of capitalist oligarchy. They take contributions from the capitalists and make policy to suit the capitalists. In the US a study has proven scientifically (by analysing whose policy wishes are implemented) that the US is an oligarchy.

“Testing theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups and Average Citizens” – Martin Gilens

I will omit the link as it put my last comment in moderation.

“Austerity does not necessarily require a cut in government spending”

There has certainaly been austerity in the UK despite no real or nominal cut in spending. This is because population growth has meant that on a per capita basis people are worse off. Given the rate of population growth we should be having 4% GDP gowth or more.

Unemployment is falling because it is being offset by under-employment and running down of savings.

For those not familiar with the UK, a court ruling has forced banks to set aside over £20 billion in repayments (to ordinary people) for “payment protection insurance” that was neither asked for, nor needed by debtors. It is this that has fuelled economic growth between June 2013 and today. That source of growth is nearly expended.

Lobby for the worse world is at it again. There far-right characters are the bane of our existence.

The error of Bershidsky, the Bloomberg author, of ignoring the denominator of a ratio, is surprisingly widespread. One wonders how the people who do that got out of middle school. 8th graders have been taught that the increase in a fraction does not mean that the numerator increased; it could mean that the denominator decreased.

This cognitive blindness has been pernicious in our current economic conditions, because, like in the Bloomberg editorial, a ratio with the GDP as denominator has been talked about without reference to the GDP, as though the GDP did not matter. Bershidsky claims that gov’t spending has increased, and then show a graph of gov’t spending divided by GDP. (!!!?????) Bloomberg should be ashamed of publishing such crap.

Larry- Huh?

Why dont you email this article to the author so he doesnt spew out this nonsense anymore on such a widely read website?