The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

No fundamental shift of policy at the Bundesbank

Last week, the Chief economist at the Deutsche Bundesbank, Dr. Jens Ulbrich gave a rather extraordinary interview to the German Magazine Der Spiegel. The interview was recorded in the article – Breaking a German Taboo: Bundesbank Prepared to Accept Higher Inflation. The sub-heading said that this marks a “major shift away from the Bundesbank’s hardline approach on price stability” and my profession apparently “hailed the decision as a ‘breakthrough'”. I wouldn’t be so sure. The Bank has a long track record of ignoring the plight of German workers and the workers elsewhere in Europe. The imposition of its ‘culture’ with its disdainful disregard for responsible economic policy on Eurozone political elites has created so much slack in Europe that even it cannot deny the mounting evidence that there is a deflationary problem. But this support for workers’ wage rises won’t last. As soon as the inflation rate exhibits the first uptick – the Bundesbank will be out there berating all and sundry about the dangers of profligacy! Leopards don’t change their spots.

The Bundesbank has a long history of being willing to sacrifice economic growth and live with persistent mass unemployment in return for low inflation. During the 1970s and 1980s, the Bank suppressed domestic growth and mass unemployment rose substantially.

It has also demonstrated a considerable disregard for its European neighbours. From the early 1970s, once the Bretton Woods system had collapsed, the Bank was always prepared to game its neighbours and force them to impose higher unemployment on their economies as part of the deal under the various manifestations of the fixed exchange rate system.

The Bundesbank relentlessly kept the mark undervalued so that the export locomotive would continue and was agressive in pushing exports onto its neighbours.

The result was that the currencies of Italy, France, Britain and other nations were constantly under attack because they were running external deficits.

Under the fixed exchange rate systems, each central bank was required (either unilaterally or in concert with the parity partner central bank, depending on the system) to intervene in the foreign exchange markets to offset the demand and supply imbalances of the various currencies.

The deficit nations faced an excess supply of their currencies in the foreign exchange markets (more orders for imports than demand for exports) and this put downward pressure on their currencies. The central bank would then have to buy up their own currency in the markets using foreign exchange reserves to eliminate the excess supply.

Alternatively, Germany was usually facing an excess demand for the mark, either through the trade surpluses or because the mark was attractive to capital inflow (given the Bundesbank’s rigid approach to price stability).

At times, the Bank would be selling huge volumes of the mark to stop its currency moving above the agreed bands within the fixed exchange rate system (for example, the snake in the 1970s and the European Monetary System in the late 1970s through to Maastricht).

The Bundesbank hated increasing the supply of marks because they feared it would be inflationary. So they regularly faced international censure for failing to do its share in keeping various exchange parities stable.

The Bank knew that the external deficit nations faced a bigger problem because their central banks would run out of foreign exchange reserves soon enough and at that point it either has to devalue and/or hike interest rates to attract capital inflow.

The external deficit nations were thus continually facing rising unemployment and the political opprobrium that came with that.

There was thus massive asymmetry in the sharing of the responsibilities to keep the exchange rates stable. Germany regularly forced devaluation and high unemployment on its partners because it refused to help stabilise the exchange rates.

The German ‘jobwunder’

Once the common currency emerged and Germany lost the ability to manipulate its exchange rate to its advantage (forget the rest), the next strategy it employed was to attack its own workers.

A reasonable argument can be made that Gerhard Schröder helped cause the Eurozone crisis. His government’s response to the restrictions that Germany encountered on entering the EMU are certainly part of the story and one of the least focused upon aspects.

Upon entering the EMU, Schröder was under immense political pressure to do something about the high unemployment in the East after reunification.

Without the capacity to manipulate the exchange rate, the Germans understood that they had to reduce domestic production costs and inflation rates relative to other nations, in order to retain competitiveness.

The Germans thus took the so-called ‘internal devaluation’ route that is all the rage in Europe now, well before the crisis; a move, which ultimately has made the crisis worse.

When Schröder unveiled his Government’s ‘Agenda 2010’ in 2003, it was clear that they were going to income support systems and ensure that Germany’s export competitiveness endured despite abandoning its exchange rate flexibility.

It was dressed up in the language of flexibility and incentive, but was based on the mainstream view that mass unemployment was the result of a workforce rendered lazy by the welfare system, rather than the more obvious alternative, that it arose due to a shortage of jobs.

The so-called ‘Hartz reforms’ were a major plank of the strategy and resulted from a 2002 commission of enquiry, presided over by and named after Peter Hartz, a key Volkswagen executive.

The aim was clear, unemployment benefits had to be cut and job protections had to go. The recommendations were fully endorsed by the Schröder government and introduced in four tranches: Hartz I to IV, starting in January 2003.

The changes associated with Hartz I to Hartz III, took place over 2003 and 2004, while Hartz IV began in January 2005.

The changes were far reaching in terms of the existing labour market policy that had been stable for several decades.

The so-called supply-side focus saw unemployment as an individual problem and advocated that continued income support should be conditional on a raft of increasingly onerous activity tests and training schemes.

Further, governments abandoned their responsibility to reduce unemployment with properly targeted job creation schemes.

Public employment agencies were privatised spawning a new private sector ‘industry’ – the management of the unemployed!

The Hartz reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market and the precariousness of work increased. Hartz II introduced new types of employment, the ‘mini-job’ and the ‘midi-job’ and there was a sharp fall in regular employment as a consequence.

Mini-jobs provide marginal employment with no security or entitlements and allow workers to earn up to 450 euros per month without paying taxes, while the on-costs for employers are significantly lower. The no tax obligations also mean that the worker receives no social security protection or pension entitlements.

The neo-liberal interpretation of these changes is that Germany underwent a ‘jobwunder’, or jobs miracle.

However the speedy increase in employment can also be viewed less optimistically.

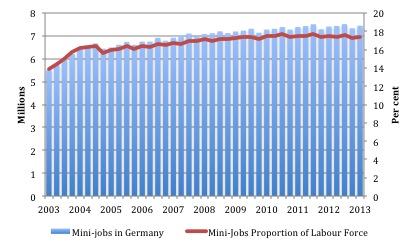

The following graph charts the history of the mini-jobs since 2003. In September 2013, there were 7.4 million ‘mini-jobs’, which represented 17.4 per cent of the labour force between 15 and 64 years of age.

The proportion has been fairly steady since late 2007 after a rapid increase in the earlier years of the scheme.

The rapid increase in mini-jobs meant an increasing (and sizeable) proportion of the German workforce were forced to work in precarious jobs with extremely low pay and were excluded from enjoying the benefits of national income growth and the chance to accumulate pension entitlements.

Pay differentials have widened considerably in Germany since 2003 and various studies have found no evidence of large-scale worker transition from ‘mini-jobs’ to other, more regular work. ‘Mini-job’ workers are increasingly trapped in this form of marginalised employment.

Massive redistribution of national income to profits

In general, German real wages (the purchasing power equivalent of the wages received by workers each week) failed to keep pace with growth in productivity (how much workers were producing each hour) and as a result there was a massive redistribution of national income to profits.

The following graph shows the – AMECO – (Annual Macroeconomic) database measure of Real Unit Labour Costs, provided by the European Commission (Annual Macroeconomic).

Please read the answer to Question 1 in the blog – Saturday Quiz – June 14, 2014 – answers and discussion – for more discussion on what RULCs mean.

Basically they are the ratio of real wages to labour productivity and if they are falling it means that productivity growth is rising faster than real wages and redistributing national income towards profits.

So the RULC measure is equivalent to the share of wages in national income. If it falls, workers have a lower share in real GDP.

The rise in the shares during the crisis signifies the fact that national GDP (output) was falling while total wages were not falling as fast or were relatively constant. As a consequence the ratio of the two rose.

Why does this matter? Until the early 2000s, real wages and labour productivity had typically moved together in Germany as they did in most advanced nations.

If real wages and labour productivity grow proportionately over time, the share of total national income that workers (wage earners) receive remains constant.

However, once the neo-liberal attacks on the capacity of workers to secure wage increases intensified in the 1980s in many nations and, later in Germany, a gap between the growth in real wages and productivity growth opened and widened.

This led to a major shift in national income shares away from workers towards profits.

The capitalist dilemma was that real wages typically had to grow in line with productivity to ensure that the goods produced were sold. If workers were producing more per hour over time, they had to be paid more per hour in real terms to ensure their purchasing power growth was sufficient to consume the extra production being pushed out into the markets.

How does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in the real wage, especially as governments were trying to reduce their deficits and thus their contribution to total spending in their economies? How does the economy recycle the rising profit share to overcome the declining capacity of workers to consume?

The neo-liberals found a new way to solve the dilemma. The ‘solution’ was so-called ‘financial engineering’, which pushed ever-increasing debt onto households and firms in many nations.

The credit expansion sustained the workers’ purchasing power, but also delivered an interest bonus to capital, while real wages growth continued to be suppressed.

Households in particular, were enticed by lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers. It seemed too good to be true and it was.

Germany adopted a particular version of this ‘solution’.

The funds to underwrite this credit explosion came from the increased profits that arose from the redistributed national income.

For some nations, such as Germany, the large export surpluses also provided the funds to loan out to other nations.

Germany didn’t experience the same credit explosion as other nations. The suppression of real wages growth in Germany and the growth in the (very) low-wage ‘mini-jobs’ meant that Germany severely stifled domestic spending up to 2005

The result was that growth (what there was) was driven by net exports and domestic demand was flat.

Schröder’s austerity policies forced harsh domestic restraint onto German workers, which meant that Germany could only grow through widening external surpluses.

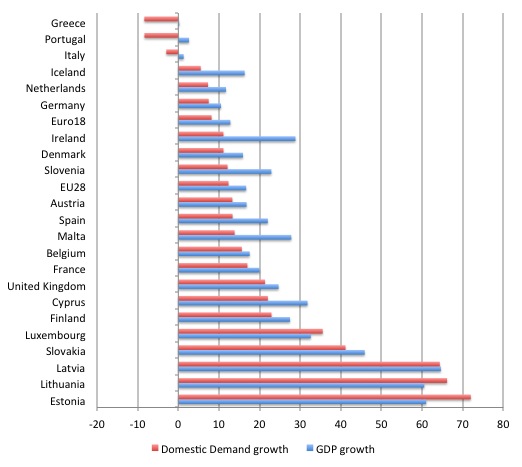

The following graph shows real GDP growth between 2000 and 2013 and domestic demand growth over the same period for a range of European nations.

You can see that Germany was one of the lowest growth nations during this period but its export of capital was creating havoc in other parts of Europe, which eventually rebounded during the crisis.

Germany is clearly getting worried. The Bundesbank has recently predicted a significant – Slowdown in economic growth in Germany.

They said that after “the economic upsurge in Germany distinctly lost momentum in the first two months of the spring quarter” with no growth predicted for the quarter at all.

The “construction sector” is in decline as is “the industrial sector”. They predicted that firms were cautious about new investment.

So much for German firms being Ricardian agents who love fiscal surpluses and will spend up big as the deficit declines into surplus.

Germany is aware that it faces a difficult period. In early July, the German government endorsed the establishment of a minimum wage at €8.50 per hour, which will take effect from January 1, 2015. Germany has never had a minimum wage in the past. But there will be exempted sectors (mini-jobs?) so it is not as good a decision as it might look.

The trade unions in Germany are also trying to catch up after a long period of virtually zero real wage increases. Earlier this year, more than 1/2 million German chemical workers received a 3.7 per cent wage rise which is well above the inflation rate.

Clearly, the Bundesbank has realised that there can be no growth in Germany without some domestic growth given the poor export environment at present.

In the days that followed, it has been reported that the – ECB backs Bundesbank call for higher German wages. The ECB Chief Economist Peter Praet claimed that this only applied to nations where “inflation is low and the labour market is in good shape” otherwise continue with austerity as instructed, and further widen the imbalances in the Eurozone.

So not much change there. And given the Bundesbank basically bullies the ECB who should be surprised they come out lock-step with each other.

The Financial Times article – Bundesbank shifts stance and backs unions’ push for big pay rises – claimed the move was “a remarkable shift in stance from a central bank famed for its tough approach to keeping prices in check”.

Other financial commentators were similarly in awe.

First, the Bundesbank has never liked deflation. It knows how dangerous that can be for financial stability and private sector solvency. The last thing it wants is a massive rise in negative equity among German mortgage holders. So there is nothing remarkable about it wanting to push inflation back up to its comfort zone.

Being obsessed with price stability does mean it encourages negative inflation rates.

Second, the Bundesbank itself quickly clarified its position. Der Spiegel says:

Sources close to Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann told the Reuters news agency that Germany would have to accept higher than desirable price increases at most in the short to medium term. A high-ranking official, who did not want to be named, said that the bank was referring to an inflation rate that lay “moderately above” the European Central Bank’s target of just below 2 percent.

Conclusion

So there is no fundamental shift in thinking going on. Germany is facing a slowdown in growth and the so-called ‘green shoots’ elsewhere in Europe might whither fairly soon unless the US keeps growth strongly.

They know they cannot suppress domestic demand forever so give a little now – for a while. That is what is going on.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill, is the source that you give the right one? “Breaking a German Taboo: Bundesbank prepared to accept higher inflation” leads me to an article from 2012 (!!) so it can’t refer to an interview from last week. Best wishes – Mellie Skorna

“Leopards don’t change their spots.”

See Gattopardo economics:

The crisis and the mainstream response of change that keeps things the same

April 2013

http://www.boeckler.de/pdf/p_imk_wp_112_2013

____________________________________________________

P.S. another missing “not”?

“Being obsessed with price stability does mean it encourages negative inflation rates.”

Dear Bill

Since 2000, productivity growth in both Germany and France has been about 1% per year. The target inflation rate for the Eurozone was 2%. That means that in both countries wages should have risen by about 3% per year. That is exactly what happened in France. In Germany, on the other hand, wages rose by about 1.5% per year. As a result, labor costs per unit, which were about the same in France and Germany in 2000, are now about 20% higher in France. The French played by the book and lost competitiveness while Germany, by ignoring the target inflation rate of 2%, became much more competitive.

Regards. James

Dear Mellie Skorna (at 2014/07/29 at 19:33)

I think the article is correct but the date is wrong for some reason.

The German version is not publicly available – you have to pay.

best wishes

bill

“Until the early 2000s, real wages and labour productivity had typically moved together in Germany as they did in most advanced nations.”

Bill,

My understanding is that in most advanced nations this post-war ‘stylised fact’ has not, in fact, been borne out. Rather productivity has typically outpaced wage growth. Am I missing something?

“Without the capacity to manipulate the exchange rate, the Germans understood that they had to reduce domestic production costs and inflation rates relative to other nations, in order to retain competitiveness.”

Not true. Only true if they want to retain competitiveness AND retain the prior levels of wealth disparity.

Germany chose NOT to distribute the burden equally.

Germany’s Energiewende is not helping. They are trying to push wind/solar, and shutting down nuclear. That is tremendously inefficient. For example the Germans have spent over $300B USD on wind/solar. For that amount of money they could have completely replaced power generation from fossil fuels.

The Germans are truly hard-working, well-trained, efficient, etc. Only they could keep things going with the stupid policies they are following. The shame is that with the same amount of hard work, they could all be living a lot better.

Sorry, replaced power generation with fossil fuels by nuclear power. With all the money they’ve spent, CO2 production levels are now rising again in Germany.

@SteveK9 – do you actually believe this?

For starters, who exactly has spent 300 billion on the move towards renewable energies? Are you talking about the subvention mechanism that has been designed in such a way that it rewards energy-hungry industries but exempting them from paying for it, while at the same time bringing down electricity prices? With the balance being pushed on private households?

Or are you talking about pure construction costs? Because as Finland currently demonstrates, nuclear power plants are extremely expensive and take forever to build. And once they’re finished, they still have to be fed fuel, extracted at high environmental and social cost, transported over long distances at high CO2 emissions.

The reason that Germany’s CO2 emissions go up have to do with the fact that nothing has been done to discourage coal burning – so with coal cheap, electricity is produced from it for export.