Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Australia’s lowest wage workers continue to trail behind

The Fair Work Commission, the Federal body entrusted with the task of determining Australia’s minimum wage handed down its – 2013-14 decision – on June 4, 2014. The decision meant that more than 1.5 million of our lowest paid workers (out of some 11.6 million) received an extra $18.70 per week from July 1. This amounted to an increase of 3 per cent (up from last year’s rise of 2.6 per cent). The Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) is now $640.90 per week or $16.87 per hour. For the low-paid workers in the retail sector, personal care services, hospitality, cleaning services and unskilled labouring sectors there was no cause for celebration. They already earn a pittance and endure poor working conditions. The pay rise will at best maintain the current real minimum wage but denies this cohort access to the fairly robust national productivity growth that has occurred over the last two years. The decision also widens the gap between the low paid workers and other wage and salary recipients. The real story though is that today’s minimum wage outcome is another casualty of the fiscal austerity that the Federal Government has imposed on the nation which is destroying jobs and impacting disproportionately on low-paid workers.

These workers are now under concerted attack since the conservatives took over the Federal government in September last year. Employers (their peak bodies) have brought a multitude of cases before Fair Work Australia challenging overtime rates, trying to scrap previously agreed enterprise bargains, attacking youth wages, trying to force adults to accept youth training wages, and, of-course, trying to erode and scrap the whole minimum wage structure.

Sad but true.

Their greed is backed up by the usual lies that minimum wages erode employment – as if these creeps care about the employment prospects of the low-wage workers anyway!

The Decision

In delivering the decision, the President of the FWC, Justice Iain Ross said that:

The real weekly earnings of full-time workers have become progressively less equal over the past decade-for each decile, the lower the earnings, the lower the rate of growth in earnings-although this rising inequality has become less pronounced in the past five years. No party disputed the fact that the distribution of earnings has become more unequal in Australia over recent decades and the Panel acknowledges that annual wage review decisions have a role to play in ameliorating inequality.

… While real earnings have generally increased over the past decade, earnings inequality is increasing. Over the past five years, the rate of growth in average earnings and bargained rates of pay have outstripped growth for award-reliant workers. This has reduced the relative living standards of award-reliant workers and reduced the capacity of the low paid to meet their needs-needs being a relative concept.

It is a pity their decision didn’t take this ‘concern’ seriously.

In parrying the complaint from employers that this would cause inflation and/or unemployment to rise, the FWC said:

The rise in labour productivity together with the low growth in wages has meant that nominal unit labour costs barely rose over the past year and real unit labour costs remained at an historically low level. In aggregate, there are no signs of cost pressures arising from the labour market.

In other words, the firms have been taking advantage of the low paid workers to increase their profitability.

The rising unemployment has nothing at all to do with excessive wages growth (relative to productivity growth). The implication of the FWC’s decision is that by cutting the real wage of the lowest paid workers the capacity to pay of the firms will improve and employment will be higher than otherwise.

The rising unemployment is the direct result of the pro-cyclical fiscal policy that the Government has imposed over the last few years in its obsessive (and failed) pursuit of a budget surplus this year.

This has damaged aggregate demand and caused sales volumes to moderate. Firms will not employ new workers if they cannot sell the extra output produced no matter how cheap the labour is. All they will do is pocket the lower unit labour costs as higher profits.

The minimum wage outcome is another casualty of the fiscal austerity that the Federal Government has imposed on the nation which is destroying jobs and impacting disproportionately on low-paid workers.

Minimum wage principles

I regularly write analytical reports for trade unions who are defending industrial matters on behalf of the members in the Fair Work Commission in Australia. That often requires me to appear as an expert witness in the relevant matter.

I am working on case at present where the employers are seeking orders from FWC to renege on several previously negotiated enterprise agreements with their workforce and force the workers back onto minimum conditions. I cannot comment much here because the case will come before the court soon enough.

But this is a growing trend and employers seem to think that under the ‘protection’ of the anti-worker federal regime in place that they can just ditch contractual agreements at will. The claim is always the same – we cannot pay the conditions we agreed. It says more about their management skill and sense of business ethics than anything else.

I have previously reported an experience last year at the FWC when I appeared on behalf of the restaurant workers who were fighting to retain their overtime rates. These are pay rates that apply for working non-standard hours (weekends, late nights etc).

The interchange with the employers’ legal counsel went according to the usual script. The usual tactic is to discredit me personally as a means of making my evidence irrelevant – bully-boy tactics.

Feigning outrage before the FWC Commissioner, the counsel said to me “you didn’t agree with the FWC decisions on minimum wages, do you?”. To which I replied that I was of the firm professional view that the minimum wage was too low in Australia and that the institutional machinery that sets it has been mistaken in not increasing it by more in the past, especially in excluding workers from sharing in productivity growth.

He then quoted from one of my earlier blogs which outlined my minimum wage principles, which I have held for as long as I became a professional economist:

In terms of minimum wage setting my view is simple. I would not have a “capacity to pay” guideline in the set of principles upon which the minimum wage is set. I would ignore cyclical patterns when considering what the level of the minimum wage should be.

I admitted that remained my view and then he said:

Advocate: So you don’t think capacity to pay matters and firms that cannot pay the minimum wage “are not suitable to operate in the economy”.

Bill: That is my view.

Much huffing and puffing followed as if the view was alien.

This is what I told the court. The minimum wage as a statement of how sophisticated you consider your nation to be or aspire to be. Minimum wages define the lowest material standard of wage income that you want to tolerate.

In any country it should be the lowest wage you consider acceptable for business to operate at. Capacity to pay considerations then have to be conditioned by these social objectives.

If small businesses or any businesses for that matter consider they do not have the “capacity to pay” that wage, then a sophisticated society will say that these businesses are not suitable to operate in their economy.

Such firms would have to restructure by investment to raise their productivity levels sufficient to have the capacity to pay or disappear.

This approach establishes a dynamic efficiency whereby the economy is continually pushing productivity growth forward and in tat context material standards of living rise.

I consider that no worker should be paid below what is considered the lowest tolerable material standard of living just because low wage-low productivity operator wants to produce in a country.

I don’t consider that the private ‘market’ is an arbiter of the values that a society should aspire to or maintain. That is where I differ significantly from my profession.

The employers always want the wages system to be totally deregulated so that the ‘market can work’ without fetters. This will apparently tell us what workers are ‘worth’.

The problem is that the so-called ‘market” in its pure conceptual form is an amoral, ahistorical construct and cannot project the societal values that bind communities and peoples to higher order considerations. I realise we could have a debate about the concept of a market being heavily embedded with ‘values’ but then we would get lost up our own ….s.

The minimum wage is a values-based concept and should not be determined by a market.

All of that is in addition to the usual disclaimers that the pure ‘competitive market, cannot exist for labour given the imbalances between workers and employers and the fact that the use value of the labour power is derived within the transaction (that is, the worker has to be forced to work). This is unlike other exchanges where the parties make the deal and go their separate ways to enjoy the fruits of their trade.

Anyway, those principles govern the way I operate as a professional and make me a ‘martian’ relative to my professional colleagues.

Staggered wage decisions and real wages

An annual wage adjustment cycle as exists in Australia means that minimum wage workers have to endure systematic cuts in their real wages more than they would if the adjustments were indexed through the year after an annual review decision.

With inflation being a continuous process (more or less), the annual adjustments by the Fair Work Commission hand employers huge gains and deprive the workers of real income in between decisions. The following discussion and diagram explain why.

Assume that at the time of policy implementation, the real Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) wage was w1 and there was no inflation. The wage setting authority manipulates a nominal minimum wage (the $ weekly value) and the real wage equivalent of this nominal wage is found by dividing the nominal wage by movements in the price level. Assume that inflation assumes a positive constant rate at Point 0 onwards.

The nominal wage is the $-value of your weekly wage whereas the real wage equivalent is the quantity of real goods and services that you can purchase with that nominal wage. For a given nominal wage, if prices rise then the real wage equivalent falls because goods and services are becoming more expensive.

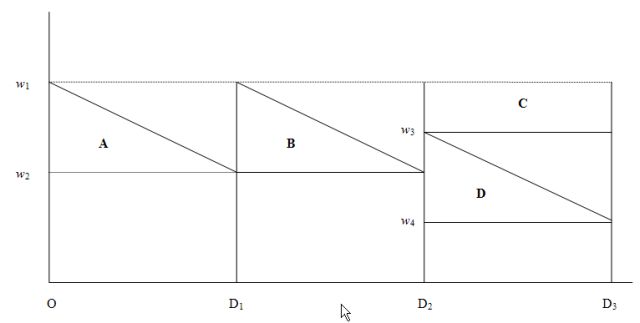

The following diagram depicts the real income losses that arise when wage adjustment is not indexed to the price level on a continuous basis – as is the case when the Fair Work Commission makes an annual adjustment in the FMW:

Over the period O-D1 the rising price level continuously erodes the real value of the nominal wage and immediately before the next indexation decision, the real wage equivalent of the fixed nominal FMW is w2. The real income loss is computed as the area A, which is half the distance (0-D1) times distance (w1-w2).

At point D1 the wage setting authority increases the nominal wage to match the current inflation rate which restores the real wage to w1, but the workers do not recoup the deadweight real income losses equivalent to area A.

The same process occurs in the period between the D1 and the next decision D2, resulting in further real income losses equivalent to area B.

These losses are cumulative and are greater: (a) the higher is the inflation rate; (b) the longer is the period between decisions; and (c) the higher is the real interest rate (reflecting the opportunity cost over time).

Clearly, the patterns of real income loss are different if the wage setting authority adopts a decision rule other than full indexation (that is, real wage maintenance). For example, say it decides not to adjust nominal wages fully at the time of its decision (or in fact at the implementation date of its decision) to the current inflation rate then the real income losses increase, other things equal.

So at time D1 the authority decides to discount the real wage (less than full indexation) and increases the nominal wage rate such that the real wage at that point is equal to w3.

Over the next period to D3, the real wage falls to w4 and at the time of the next decision (implementation time D3) the real income losses would be equal to the triangle D (reflecting the inflation effect over the period D2- D3, plus the rectangle C, which reflects the losses arising from the decision to partially index at D2.

Similarly, one can imagine that the adjustment at a particular time might involve a real wage increase (more than full compensation for the current inflation rate) which would then partially offset some of the real income loss borne in the previous period when nominal wages were unadjusted but inflation was positive.

So if you understand the saw tooth pattern of indexation shown here you will see that the triangles A and B represent real losses for the workers between wage setting points even if real wage maintenance is the preferred policy.

These losses are worse (areas C and D) if there is only partial adjustment. These losses occur because inflation is a more continuous process than the adjustments in FMW and accrue to the employer. The employers are pocketing these wage losses every day because their revenue is geared to the price rises and they are paying constant nominal wages to the workers.

The other problem is that the usual source of growth in real wages for workers is to share in the productivity growth of the nation. Workers not reliant on the annual Federal minimum wage adjustment achieve that through their enterprise bargains although over the last twenty years even those workers have been mostly unsuccessful in achieving a proportionate increase in real wage relative to productivity growth as sequential federal governments have legislated against trade unions and undermined the capacity of workers to bargain on a reasonable basis.

Wage Parity

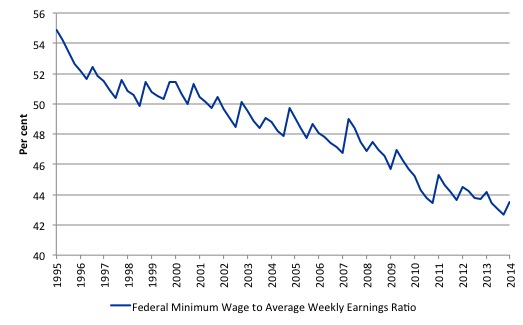

In terms of parities with other wage earners, the following graph shows the ratio of the Federal minimum wage to the Full Time Adult Ordinary time earnings series provided by the ABS (the latest being for the December-quarter 2013). This series in now bi-annual (previously quarterly). I have interpolated on the basis of the most recent growth (2.9 per cent – a slight real wage increase).

I simulated this series out to September-quarter 2014 (the quarter in which the latest FWC Annual Wage decision will start impacting) based on a constant growth in earnings (assessed over the last 12 months). The new FWC applies from July 1, 2011 so will be constant over the rest of the 2014-15 financial year.

The logic of the neo-liberal period which encompasses the data sample shown (and then some) was to at least achieve cuts at the bottom of the labour market, given that workers with more bargaining power would put up resistance against generalised cuts.

Successive minimum wage decisions have forced workers at the bottom of the wage distribution to fall further behind in relative terms.

In the December-quarter 1993, minimum wage workers earned around 55 per cent of the Full Time Adult Ordinary time earnings. By June 2014, this ratio will have fallen to 44 per cent. There has been a serious erosion of parity over the last 18 years.

Another way of looking at this dismal outcome is to compare the movement in the Federal Minimum Wage with growth in GDP per hour worked (which is taken from the National Accounts). GDP per hour worked is a measure of labour productivity and tells us about the contribution by workers to production.

Labour productivity growth provides the scope for non-inflationary real wages growth and historically workers have been able to enjoy rising material standards of living because the wage tribunals have awarded growth in nominal wages in proportion with labour productivity growth.

That relationship has been severely disrupted by the neo-liberal attacks on unions, wage fixing tribunals and other legislative initiatives that have eroded the capacity of workers to share in labour productivity growth.

The widening gap between wages growth and labour productivity growth has been a world trend (especially in Anglo countries) and I document the consequences of it in this blog – The origins of the economic crisis.

But the attack on living standards has been accentuated at the bottom end of the labour market.

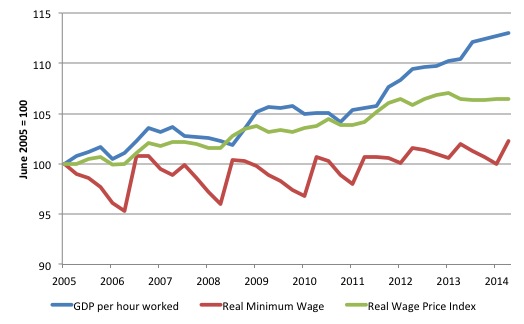

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (red line), GDP per hour worked (blue line), and the Real Wage Price Index (green line), the latter is a measure of general wage movements in the economy. Th graph is from June 2005 up until June 2014 (indexed at 100 in June 2005).

By June 2014, the respective index numbers were 113 (GDP per hour worked), 106 (Real WPI), and 102.3 (real FMW). It means that minimum wage workers in Australia are largely excluded from sharing in any of the productivity growth that the nation has enjoyed over the last nine years.

The wage tribunals are only maintaining the real standard of living that these workers had 9 years ago. I call that a disgrace.

Of-course, like all graphs the picture is sensitive to the sample used. If I had taken the starting point back to the 1980s you would see a very large gap between productivity growth and wages growth, which has been associated with the massive redistribution of real income to profits over the last three decades. Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

Staggered adjustments in the real world

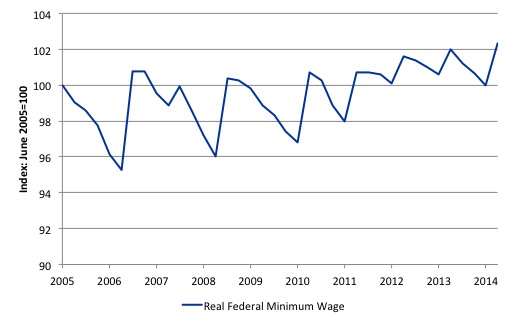

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) since June 2005 extrapolated out to September 201w (the quarter in which today’s decision will start impacting) based on a constant (current) inflation rate. You can see the saw-tooth pattern that the theoretical discussion above describes.

Each period that curve heads downwards the real value of the FMW is being eroded. Each of the peaks represents a formal wage decision by the Fair Work Commission. If the trough in the saw-tooth lies below the 100 line on the vertical axis then the real wage falls by the end of the period.

If the trough lies above the 100 point then the inflation during the year after the last wage decision has not fully eroded the real wage increase and so there is some modest net real wage increase for Federal minimum wage workers over the period.

In the last two decisions, there has been some very modest real income retention by these workers

But in the last year, the 2013 decision has been completely inflated away, leaving the minimum wage workers with the real wage equivalent that they had in June 2005.

Further, When the workers get the pay rise on July 1, 2014 their real wage equivalent of the nominal FMW will just catch up to its level one year ago.

So while each adjustment provides some immediate real wage gain for workers, those gains are ephemeral and the inflation process systematically cuts the purchasing power of the FMW significantly by the time the next decision is due – these are permanent losses.

I used the Consumer Price Index to deflate the Federal Minimum Wage to create the real series. The CPI is, in fact, a very limited measure of the cost of living. In May 2011, the ABS published their – Analytical Living Cost Indexes for Selected Australian Household Types – which provided more detailed analysis of the impact of price rises on different household and worker cohorts.

Those on low pay are likely to be significantly worse off than the raw CPI figures suggest.

Minimum wages and employment

For a discussion of this topic please see the blog – Low pay workers dudded again in Australia.

I thought this little piece of copy-cat analysis from the CEPR (originally from Goldman) in the US – 2014 Job Creation Faster in States that Raised the Minimum Wage – was very neat. Essentially, the evidence is that:

At the beginning of 2014, 13 states increased their minimum wage … employment growth was higher in states where the minimum wage went up. While this kind of simple exercise can’t establish causality, it does provide evidence against theoretical negative employment effects of minimum-wage increases.

That should really be the end of it.

International comparisons

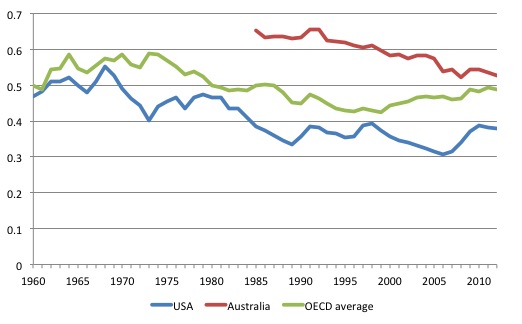

In the early 1960s, the minimum wage in the US was equal to around 50 per cent of the median wage. In other nations, it has been set higher than that with the OECD average being close to 60 per cent and for Australia, close to 65 per cent.

The following graph shows the Ratio of Minimum to Median Full-Time Wage for Australia, the United States and average for the OECD Countries from 1960-2013.

Its happening everywhere! When there were systematic attacks on workers previously, which successfully undermined their material standards of living, Marxism became popular and workers revolted in the streets. Subsequently trade unions formed, gained membership, and forced governments to adopt social democratic policies. It took, maybe 50 years for that evolution to occur.

Hopefully, the fightback will begin earlier in this phase.

Conclusion

While the $18.70 per week increase is welcome it will still result in real wage maintenance at best and excludes the lowest paid workers from sharing in the national productivity growth that has been fairly robust in the last year.

It is also insufficient to restore the relativities at the bottom of the labour market which have been eroded over recent years.

In that regard, the decision does not redress the significant erosion of real purchasing power that low-paid workers have suffered over the last decade.

I would also note that a sophisticated society requires a decent minimum wage that is determined on the basis of what we want the floor in living standards to be. In the absence of regulation it is almost certain that the ‘market’ would drive the wage below that level.

Australians should resist the current push by the well-networked employer groups, aided and abetted by the lying Federal government, to undermine workers conditions further.

The deprivation of the low paid workers is directly the fault of the Federal government’s mismanagement of fiscal policy. If growth had have been higher, then it is likely the FWC would have awarded a higher minimum wage increase.

I will write more about the US decision to raise minimum wages in due course.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Anybody who thinks we don’t have a class based social order in Australia is off with the pixies.This is the root cause of so many of our social ills and has been since 1788.The so called “Fair Work Commission” is a prime example.It certainly pertains to work but there is nothing fair about it. What can you expect of Howard (The Rodent) et al who dreamt up this noxious entity.

BTW – maybe we need more “Martians”.

Wondered what put the fire in your belly. Now I know.

In the trenches defending less fortunates against Rottweilers (who think its just a game) employed by social Neanderthals (who think themselves alpha-beings, but are running the show by mere chance).