I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Life-time employment and employment guarantees

In the Sydney Morning Herald print edition today (later found in the Tapei Times there was an interesting article – Japan pays a price for lifetime jobs about the way the Japanese are coping with the recession. The story documents the Japanese life-time employment approach which explains why that country can have lower unemployment rates even though its economy is contracting fast. However, once you think about his scheme you realise that it is not without problems. The sentiment and collective will is admirable. But there is a superior buffer stock approach available which also embraces these social values but delivers better outcomes overall – I call it the Job Guarantee.

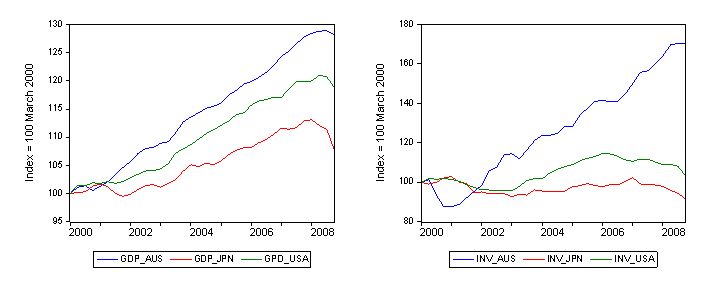

First of all, I assembled some data to see what was happening in Australia, Japan and the US as the world economy contracted. The first graph is the relative performance of Australia, Japan and the US in terms of GDP and Gross Fixed Capital Formation. All data is from the OECD quarterly Main Economic Indicators. I took a sample from March 2000 through to December 2008 and indexed it at 100 at March 2000. The indexing provides a quick view of the relative performance of the three economies as they went into recession (in the latter part of the sample). It is clear that all three economies are now slowing.

Official data from Japan shows this is the worst downturn for the economy since 1955. The situation in the first quarter of 2009 (not shown in the graphs) worsened and GDP fell by 15.2 per cent over the previous 12 months.

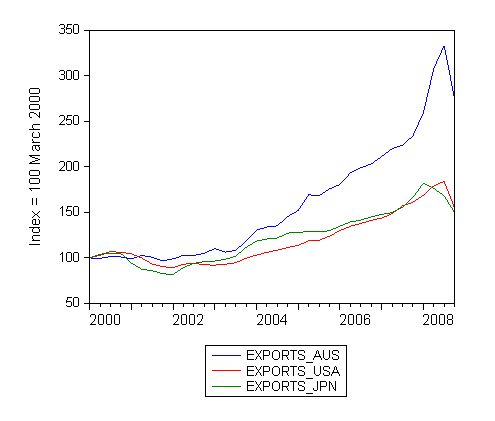

The second graph shows the impact of the primary commodities boom in the last 5 years and its tapering in the last year. The data is of exports and is again indexed at March 2000 = 100 for easy comparison. Up until early 2003 there was no real difference in the export growth for the three countries but as primary commodity prices boomed Australia’s export value increased dramatically. Then as the GFC started to impact on the real global economy, export values dipped sharply for all countries.

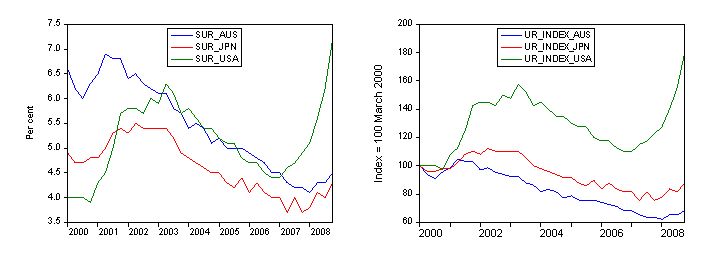

Now we consider the labour market ramifications of the slowdown. The following graph shows the actual Standardised OECD unemployment rates for Australia, Japan and the US from March 2000 (left-hand panel) and the same data indexed at March 2000 to 100 (right panel). The results are stark. Even with the booming relative GDP performance (driven heavily by investment and export growth), Australia still could not achieve a superior unemployment to Japan over this period. The picture is more gloomy for us because the data ends at December 2008. Australia’s labour market has deteriorated further in 2009 relative to Japan, even though the Japanese economy seems to be incurring more significant damage as a result of the global slowdown than Australia.

While the Japanese economy is now contracting sharply after enjoying modest growth between 2003 and 2007, its unemployment rate is still very low and has risen marginally as the contraction has deepened. Compare that to the sharp rise in the US unemployment rate as its economy has contracted. The US experience is mirrored in the European countries where unemployment rates approaching 10 per cent now are the norm.

The article – Japan pays a price for lifetime jobs poses the question:

The country faces its worst economic crisis since 1955, but unemployment remains low. Why?

The report cites the example of the “High Metal Company in Osaka, Japan” which is a small business and suffered a 50 per cent decline in orders in the first half of October. The manager never considered laying off the workers but instead introduced some new in-house employment schemes – “an indoor vegetable garden” and “a handicrafts workshop”

The indoor garden has been a big success and “in the last three months” the company has

… installed rows of parsley, watercress and other plants, using factory space that has been empty since the company disposed of unused machinery. High Metal’s staff tend the sprouts religiously, topping up the water supply, adding fertilizer and adjusting the fluorescent lights.

One of the reasons the company can maintain its workforce is because it receives Japanese government subsidies to keep them on.

This example is common across Japan. Workers who would otherwise be idle as orders fell are engaged in street sweeping and community tasks but remain on their company payroll. In other words, the Japanese Government chooses to maintain “lifetime” employment using fiscal policy to help firms hold labour as orders fall.

The firms use all the other adjustments available to them before shedding labour. Japan has a “buffer stock” of companies that take up the slack when demand is high and disappear as economic activity slackens. They are loosely attached to the bigger firms but are considered temporary. Firms also reduce overtime, cut performance bonuses and negotiate lower supply contracts as they try to adjust to the declining spending.

The temporary sector serves a “buffer stock” function for the Japanese economy and firms deliberately maintain relationships with small-scale producers who pay lower pay and offer insecure employment. This sector may be as large as 30 per cent of the Japanese labour force. But its existence allows the primary labour market to offer better conditions to its workers including life-time employment.

So that is why the unemployment rate is not dancing in tune with the output side of the economy in the same way it does in Australia, the US and European economies.

But is this the best way to maintain a buffer stock of workers?

First, workers are more likely to accept substantial wage cuts in Japan in return for keeping their jobs. Firms save on wages and get the Government subsidy, presumably maintaining some profit margin. But wages are at the same time a cost and an income and wide scale wage cutting will always damage aggregate spending.

As a consequence, the domestic demand conditions worsen and employment growth falters some more. Wage cuts are not the way to deal with a demand-deficient economy.

Second, it is often thought that recessions are cathartic periods where high cost firms are expunged (and die) making way for new investment in best practice technology. So firms that survive the recession are likely to have increased their productivity levels and the weaker low productivity firms disappear forever. Once growth resumes, the economy is alleged to be in better shape than before.

There is mixed evidence for this idea. But in general recessions probably to have a cleansing impact on the private sector capital stocks and better capital survives.

In this context, critics of the Japanese life-time employment scheme claim that it creates a sclerosis – by “keeping alive businesses that are no longer competitive and perhaps whose productive era is over” (see article for quotation source).

The Job Guarantee proposal also offers a buffer stock function to the economy but does not subsidise private employment nor would it allow firms to cut wages of its employers significantly.

The Job Guarantee provides an unconditional job offer to anyone that wants to work at the minimum wage. It provides a wage floor and a nominal inflation anchor to the economy. It would maintain low unemployment by allowing firms to shed labour when their sales no longer justify the output levels required to employ the workers and shift the workers into the public sector.

At present, these workers are shifted into the public sector but become unemployed. In a Job Guarantee world, the workers would immediately be re-employed and receive the minimum wage plus other statutory entitlements (such as holiday and sickness pay etc). Given that recession impacts most on the lower wage workers anyway, the actual pay loss under a Job Guarantee scheme would be relatively low and probably not as great as the workers suffer in the Japanese life-time employment schemes.

In Japan, firms are allowed to cut pay by up to 40 per cent and still qualify for the life-time employment subsidy. So any workers within 40 per cent of the federal minimum wage would be no worse off under the Job Guarantee. Further, private firms would have a disincentive to cut wages for fear that their workers would flood into the secure Job Guarantee sector.

It is also likely that the Job Guarantee would have more scope to engage in broader community employment which would probably deliver greater benefits to the society than the schemes that the Japanese firms dream up to engage their labour while times are tough.

There would also be no reason why the firms would not re-employ their former workers out of the Job Guarantee pool once their sales justified expanding employment. The Job Guarantee wage will not prevent that from happening although workers who are paid just above the minimum wage at present may ultimately prefer the working environment in the Job Guarantee. This would force firms to improve their job conditions to attract the labour back once economic activity improved. That is hardly a problem. It is likely to be a stimulus for better pay, better conditions and higher productivity.

The other advantage of the Job Guarantee is that it allows the non-productive capital to disappear during the recession. The Job Guarantee would take care of the unemployment problem without compromising the “cleansing process” in the private capitalist economy.

Overall, while the way Japanese firms demonstrate commitment to their workers puts our employers to shame, I think a government-financed Job Guarantee scheme to be a superior way to insulate workers from the ravages that recession brings.

Dear Bill,

What has been the feeling / opinion from the business community about the Jobs Guarentee? My guess is not very well given how enthusiastically many of them embraced Work Choices.

Cheers, Alan.

Dear Alan

In general they do not like it for reasons you advance.

best wishes

bill