The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Argentina and Greece – credible analogy or not?

There was a article in the UK Guardian yesterday (May 21, 2013) – No, Argentina is not a ‘cautionary tale’ for the eurozone. The basic tenet of the article, written by a Greek journalist is that there is no applicable analogy that can be drawn between the experience of Argentina during its crisis in 2001-2002 and the current crisis in Greece. The author rejects any attempts to draw a comparison because Greece would have to introduce a new currency and this would mean no-one would agree to hold it and this would prevent Greece from purchasing essential imports. The author claims that all Argentina had to do was break a pegged arrangement. My view expressed in this blog is that while there are technical differences in the way the monetary system would change in Greece if it abandoned the Euro and what happened in Argentina, the similarities between the two cases are greater. There is an applicable analogy and it scares those who want to hang onto the Euro at all costs.

This morning I spent some hours in the courts at Fair Work Australia in Melbourne giving expert evidence on behalf of the United Voice union, which represents low paid workers in a number of sectors.

The current hearing was brought to the court by employers in the restaurant and cafe’s industry seeking to abandon the legal penalty rates, which apply to work on weekends and public holidays.

I was asked by the union to respond to evidence provided on behalf of the employers by a professor who seems to believe in the applicability of textbook marginal productivity theory to the real world.

The hearings will continue to some weeks and once a decision is made I will comment publicly on the evidence given by both sides.

Australia has an adversarial industrial relations system where the legal teams on both sides hack into the reputations of the witnesses used by the opposite side. It’s not very pleasant. More later on that.

Now back to Greece.

Before the author began his argument the reader was confronted with this picture depicting unemployed people sitting in front of a sign in Buenos Aires, which reads “hunger”.

Its unclear what the picture is doing in the context of the argument other than to say the obvious. There was a sharp rise in unemployment in 2001 and 2002 in Argentina as its crisis unfolded. There was a sharp drop in per capita income and people suffered badly. I will come back to that issue presently.

Okay, here is another graphic in a different language – which says “Don’t Underestimate the Hunger”.

What does it prove? That unemployment is a curse that capitalist systems are prone to visit on the workers and should be prevented from occurring. It tells us that the unemployed endure harsh times when they lose their income and governments should use their capacity to avoid this capitalist tendency.

The basic claim of the UK Guardian article is that commentators draw two false analogies when they analyse the predicament of Greece.

1. “the first draws parallels between the present situation in the eurozone periphery with the crisis in Argentina in 2001”

2. “the second, especially popular in the British press, compares the European unification process with the federalisation of the United States of America”.

Okay, I am guilty of thinking that both analogies have relevance to the Greek situation. So what is the dispute?

The UK Guardian author, Nikos Chrysoloras from the Greek news service – Ekathimerini – makes the obvious points that proponents of keeping Greece in Depression but maintaining the Euro as their curency make.

His argument about Argentina rests on technicalities of whether a peg against the dollar (Argentina from the early 1990s to the crisis in 2001) is fundamentally different to abandoning one’s currency altogether and adopting the Euro.

He says:

Argentina, like dozens of countries before and after it, had opted to peg its currency to another, namely the dollar. In fact, this is not unusual in international economics. The 17 members of the eurozone, on the other hand, have chosen to denounce their own currencies and “irrevocably” adopt another.

Was it irrevocable? Just as the Euro member nations adopted the new currency because they thought it would bring them benefits so they can ditch it given it has delivered massive damages. There is nothing irrevocable about the choice of a currency unit or monetary system structure. Inertia means they take a long time to change – Bretton Woods was dysfunctional for years before the Americans finally pulled the pin.

But the pin was pulled.

The Guardian article then said:

I sometimes wonder how the hell people cannot see the difference here: the drachma, the lira, the deutsche mark, simply do not exist today. Hence, no one can unpeg them from the euro or the dollar. Let me put it another way: Argentina devalued its own currency; Greece will have to introduce another one. The new currency will not be the drachma of the 1990s. It will just have the same name as the drachma.

There is a difference – obviously. But the similarities and their consequences dwarf these difference. Argentina had lost control of its currency by pegging and running up debt (public and private) in US dollars. They were continually reliant on export income to remain solvent. Once their export markets became recessed they were unable to pay their foreign-currency debts.

Further, by abandoning the peg, they effectively created the same dilemma as Greece would do if it abandoned the Euro. They had massive liabilities in a foreign currency and had to take their chances on default.

And, once they abandoned the peg (because they could not longer gain the foreign exchange reserves to maintain it), Argentina’s currency went into freefall for a while, with all the negative short-term consequences that come with that dynamic. Greece would face the same future. I will come back to that.

Nikos Chrysoloras then admitted he had overcooked his initial claims by saying:

True, no decision in politics is truly irrevocable. So the Cypriots or the Greeks, for example, could choose to ignore the logistical chaos of abandoning the euro and print a new currency.

So, as above, the decision to enter the Eurozone was not irrevocable. So the decision on whether to leave should be made on whether the long-term costs are less than the benefits. It is almost impossible to argue that Greece will enjoy long-term prosperity as a member of the Eurozone. Even when growth eventually returns, the member states are only the next aggregate demand downturn away from re-entering the miasma of Depression.

Nikos Chrysoloras disagrees. He says that:

But will the new currency, which will be issued by effectively bankrupt states, have any exchange value whatsoever? Will the Russians accept it in exchange for oil, and the Americans in exchange for medicines? Especially Greece, which, unlike Argentina, is not a net exporter of raw materials (or any materials for that matter), will have no means to support the new currency. Greeks can print as much as they like of it, but will they be able to buy electrical appliances, cars or even foods produced abroad with it? The answer is no. Sure, they will be holding real money in their hands, but they will still be “poor”, probably much poorer than they are now.

Which is a very curious argument to make. It essentially amounts to saying that Greece has nothing to offer anyone. I have been to the islands – they are not nothing! Don’t they make ships and aren’t they one of the largest shipping service providers in the world?

The point is that if Greece has nothing to offer anyone and hasn’t enough production to sustain a good life without trade then Euro or not their future is bleak.

But since when did they just run out of such capacity? Did that happen in 2008, when they plunged into deep recession which has become a Depression because the Euro membership and a recalitrant central bank has prevented them expanding budget deficits to meet the vast output gap they faced?

Hardly. Greece is not in the state it is in because they have run out of resources that other nations might find attractive.

In this 2012 blog – A Greek exit would not cause havoc – I provided a detailed account of what happened in Argentina.

Here is a summary. In April 1991, Argentina adopted a rigid peg of the peso to the dollar and guaranteed convertibility under this arrangement. That is, the central bank stood by to convert pesos into dollars at the hard peg.

This decision was totally unsuited to the nation’s trade and production structure. In the same way that most of the EMU countries do not share anything like the characteristics that would suggest an optimal currency area, Argentina never looked like a member of an optimal US-dollar area.

It faced quite different external shocks to those that the US had to deal with. The US predominantly traded with countries whose own currencies fluctuated in line with the US dollar. Given its relative closedness and a large non-traded goods sector, the US economy could thus benefit from nominal exchange rate swings and use them to balance the relative price of tradables and non-tradables.

Argentina was a very open economy with a small non-tradables domestic sector. So it took the brunt of terms of trade swings that made domestic policy management very difficult.

Convertibility was also the idea of the major international organisations such as the IMF as a way of disciplining domestic policy. While Argentina had suffered from high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s, the correct solution was not to impose a quasi-currency board arrangement.

Both monetary and fiscal policy were constrained by the arrangement. The central bank could only issue pesos if they were backed by US dollars (with a tiny, meaningless tolerance range allowed). So dollars had to be earned through net exports which would then allow the domestic policy to expand.

After the peg was introduced, the neo-liberals made matters worse with wide scale privatisation, cuts to social security, and deregulation of the financial sector, the latter which burdened the economy with massive amounts of foreign-currency denominated debt.

Things started to come unstuck in the late 1990s as export markets started to decline and the peso became seriously over-valued (as the US dollar strengthened) with subsequent loss of competitiveness in the export markets.

Lumbered with so much foreign-currency sovereign debt the decline in the real exchange rate (competitiveness) was lethal and the domestic economy in the late 1990s was mired in recession and high unemployment. The unemployment rate was around 16 per cent in 1999.

The bond markets then introduced the “Greek scenario” – they realised the nation would become insolvent as exports collapsed and so yields on sovereign debt rose.

In 2000, under direct orders from the IMF (with the threat of refusal to maintain financial assistance), the government tried to implement a fiscal austerity plan (tax increases) to appease the bond markets – imposing this on an already decimated domestic economy.

The government believed the rhetoric from the IMF and others that this would reinvigorate capital inflow and ease the external imbalance. But at the time it was obvious that it was only a matter of time before the convertibility system would collapse. They couldn’t hold back the flood waters.

Why would anyone want to invest in a place mired in recession and unlikely to be able to pay back loans in US dollars anyway? Think about this in terms of the UK Guardian writer’s assertion about the future of Greece with a new currency (above quote).

In December 2000, an IMF bailout package was negotiated but further austerity was imposed. No capital inflow increase was observed. That was also an obvious prediction apparently not in the IMF forecasting model’s capacity to provide.

The government was also pushed into announcing that it would peg against both the US dollar and the Euro once the two achieved parity – that is, they would guarantee convertibility in both currencies. That was an impossible ask.

Economic growth continued to decline and the foreign debts piled up. The government (April 2001) forced local banks to buy bonds (they changed prudential regulation rules to allow them to use the bonds to satisfy liquidity rules). This further exposed the local banks to the foreign-debt problem.

The bank run started in late 2001 – with the oil bank deposits being the first which led to the freeze on cash withdrawals in December 2001 and the collapse of the payments system.

The riots in December 2001 brought hometo the Government the folly of their strategy. In early 2002, they defaulted on government debt and trashed the currency board. US dollar-denominated financial contracts were forceably converted in into peso-denominated contracts and terms renegotiated with respect to maturities etc.

This default has been largely successful. Initially, FDI dried up completely when the default was announced. However, the Argentine government could not service the debt as its foreign currency reserves were gone and realised, to their credit, that borrowing from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would have required an austerity package that would have precipitated revolution. As it was riots broke out as citizens struggled to feed their children.

Despite stringent criticism from the World’s financial power brokers (including the International Monetary Fund), the Argentine government refused to back down and in 2005 completed a deal whereby around 75 per cent of the defaulted bonds were swapped for others of much lower value with longer maturities.

The crisis was engendered by faulty (neo-liberal policy) in the 1990s – the peg and convertibility. This faulty policy decision ultimately led to a social and economic crisis that could not be resolved while it maintained the currency board.

What happened after the nation abandoned the peg and restored full currency sovereignty?

As soon as Argentina abandoned the peg/convertibility, it met the first conditions for gaining policy independence: its exchange rate was no longer tied to the dollar’s performance; its fiscal policy was no longer held hostage to the quantity of dollars the government could accumulate; and its domestic interest rate came under control of its central bank.

At the time of the 2001 crisis, the government realised it had to adopt a domestically-oriented growth strategy. One of the first policy initiatives taken by newly elected President Kirchner was a massive job creation program that guaranteed employment for poor heads of households. Within four months, the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar (Head of Households Plan) had created jobs for 2 million participants which was around 13 per cent of the labour force. This not only helped to quell social unrest by providing income to Argentina’s poorest families, but it also put the economy on the road to recovery.

Conservative estimates of the multiplier effect of the increased spending by Jefes workers are that it added a boost of more than 2.5 per cent of GDP. In addition, the program provided needed services and new public infrastructure that encouraged additional private sector spending. Without the flexibility provided by a sovereign, floating, currency, the government would not have been able to promise such a job guarantee.

Argentina demonstrated something that the World’s financial masters didn’t want anyone to know about. That a country with huge foreign debt obligations can default successfully and enjoy renewed fortune based on domestic employment growth strategies and more inclusive welfare policies without an IMF austerity program being needed.

The clear lesson is that sovereign governments are not necessarily at the hostage of global financial markets. They can steer a strong recovery path based on domestically-orientated policies – such as the introduction of a Job Guarantee, which directly benefit the population by insulating the most disadvantaged workers from the devastation that recession brings.

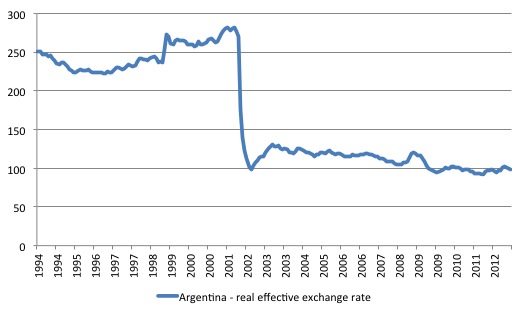

The following graph shows the REER for Argentina from January 1994 to October 2012.

It peaked in October 2001, just before the crisis really began and by January 2002 it had fallen to 62.1 (Indexed at 100 as at October 2001). The low point came in June 2002 (index number was 34.8), after which it rose and stabilised around 45. It certainly depreciated but with it came a massive boost to international competitiveness.

The nominal depreciation created a major change in the trade sector. Argentine exports became much cheaper and demand grew rapidly at the same time as import demand fell because of the rise in prices in the newly restored local currency.

It also turned out that the rise in China helped Argentina via soya bean exports which helped stabilise the currency. In general agriculture started booming.

The Government also sought to take advantage of the massive shift in relative prices (terms of trade) by providing incentives for import substitution. The tourism industry also grew rapidly as a result of the currency depreciation.

Before too long, the peso started appreciating again but by then the economy was on a solid growth footing with strong social welfare spending to maintain domestically-sourced growth and a booming export sector.

In the mid-2000s the Government actually had to take measures to stop the peso appreciating further given the size of its trade surplus. The central bank acquired huge stockpiles of foreign reserves (USDs mainly) by selling pesos in the foreign exchange market. The exchange rate is now relative stable at the higher value.

The foreign exchange intervention of the central bank (selling pesos) is sterilised by issuing government debt which is a quite different operation to the current ECB claims that it is sterilising its SMP. But that is another issue again.

So is any of that applicable to Greece? Of-course it is. Greece would suffer the same short-term collapse in its currency. But in Argentina’s case it is clear that people still wanted to buy the currency on foreign exchange markets even with the massive default and the plunging value.

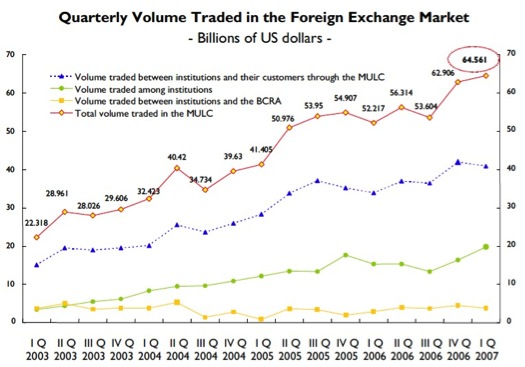

In this report from the Banco Central de la Republica Argentina (BCRA) – Report on the foreign exchange market performance. First quarter of 2007 – you see that international buyers of the depreciating currency were many.

Here is a sequence of graphs taken from that Report that highlight the massive changes that occured once the peg was abandoned and the exchange rate liberated.

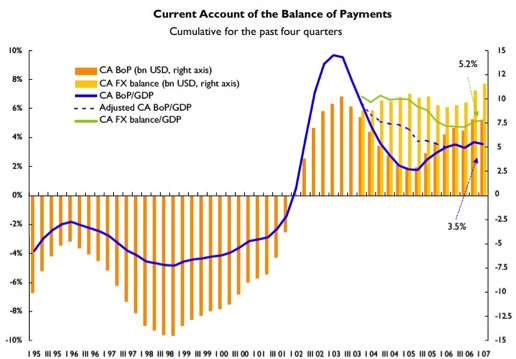

The first shows the swing in the Current Account. I know there are readers of my blog who vehemently deny that exchange rate depreciation improves competitiveness and claim that it is a neo-classical position to take to suggest such a thing. Neither is true.

Here are the facts for Argentina between 1995 to 2007:

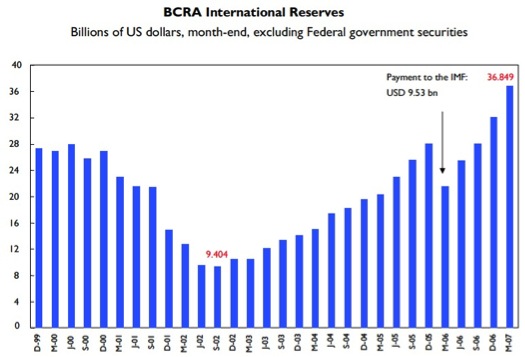

So no-one would want a currency in free fall? The second graph shows the movement in USD reserves held by the BCRA between 1999 and 2007. They nearly ran out in 2002. The question you need to ask yourselves: where did they get these dollars from?

The final graph in this sequence shows the volumes of foreign exchange transactions for Argentina between 2003 to 2007. It is hardly descriptive of a necrotic foreign exchange sector.

It is true that the Greeks do not have large quantities of natural resources like Argentina did when it defaulted and floated in 2001-02 but it is equally untrue to say it has no desirable assets that are exchange rate sensitive. I noted its tourism capacity and its ship-building industry among others.

But the other point the Guardian author ignores is that Argentina also created new export capacity given the shift in its competitiveness. Greece would do the same.

But, initially, I predict that there would be a boom in tourism virtually immediately and investment funds would flow into it. I know the argument that the tourist industry has been rundown and would not be attractive. With a currency say 30 per cent below the Euro (in real terms compared to now) thousands would be flooding into the islands no matter how rustic the experience was.

And just like Argentina, the change in the current account would put a floor into the currency fall.

Further, in the same way that Argentina had to bear a major inflation impulse as its currency depreciated, which eroded real living standards, the reversal in standards was just as swift as the currency appreciated again on the back of renewed growth.

Greece would experience the same dynamic as the Germans flooded into the sunny Greek islands to escape the Berlin winter.

The UK Guardian article fails to address any of these issues. He just asserts no-one would want to buy anything Greece has to offer. I don’t believe that at all. Capitalism chases growth. Greece would grow almost immmediately it defaulted and restored its currency. Life would be tough for a while but no worse than it is going to be for years into the future under the current plan with no growth dynamic in sight.

He also raises another “more obvious difference between the eurozone and Argentina””

The government of Buenos Aires chose to unpeg its currency from the currency of a foreign nation. In the case of eurozone, the single currency is the most crucial part of an immensely complicated structure of unified decision-making we came to call the European Union. Like the euro, the EU is also a unique construct in modern history and all analogies drawn between it and other cases of economic crises are unfounded. The EU is based on the premise of an “ever closer union”. Sure, you can slow down the whole process and even bring it to a halt, as the British government demands. But if you put it in reverse gear by dissolving the euro, this will trigger a chain reaction of “renationalising” that will bring the EU to an end. And that is only the best-case scenario. In fact, the most likely scenario is that the chaos that would ensue immediately after the dissolution of the euro would lead to the sudden death of the EU. It doesn’t take a genius to understand that the economic, political and geostrategic stakes are immensely higher for the eurozone member states than they were for Argentina in 2001. I am not arguing that such an eventuality is impossible, but it will be like nothing we have seen before, just as the EU is like nothing we have seen before.

The argument has validity. But the facts are that Greek resources – its labour, capital, and land – can be deployed productively by a national currency even if the institutional surrounds collapse.

If the EU structures have become so burdensome and damaging then why hang on to them? I actually support the political ambitions of the European Project. But trying to extend that project to a common currency has been a disaster and provides no scope under current circumstances for enduring prosperity.

I haven’t the time to discuss his second point about the “United States of Europe”. I don’t agree with that and I might address it in another blog.

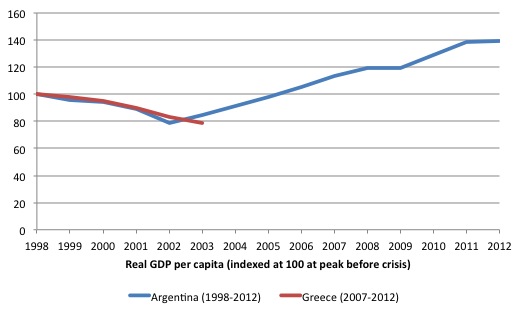

But consider the following two graphs. The first shows real GDP per capita indexed at 100 at the peak before the crisis, which in Argentina’s case was 1998 and for Greece 2007.

Argentina’s trough was reached in 2002 (index value 78.5) whereas in the five-year period since Greece plunged into its Depression the index has dropped to 78.5 and has still some way to go yet.

You can see the sustained growth that Argentina enjoyed in real per capita income once its recovery took hold.

Is anyone actually imagining that Greece will turn its current situation around as quickly as that.

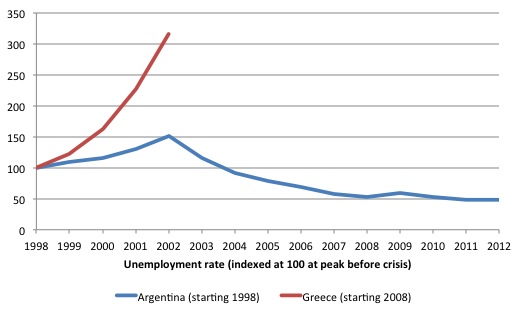

The second graph shows the employment rate indexed at 108 slow point before the respective crises. So for Argentina the year was 1998 and as you can see the unemployment rate increased by more than 50 percent.

But once growth resumed in 2002 the employment rate fell rather quickly and the economy has sustained that performance since.

Compare that to Greece’s labour market. Its unemployment rate is now three times higher than it was in 2008 and there’s no end to the spiral in sight.

Conclusion

The reality is that Argentina, in part, provides a model for all nations that have surrendered their currency sovereignty courtesy – either via a peg of some sort of outright use of foreign currencies (as in the Euro case).

That is why the elites are working hard to disabuse us of the notion that Argentina is broadly applicable. They know that the nation effectively got away with a major default, enjoyed renewed FDI and have been growing more or less continuously ever since.

They don’t want anyone to get any ideas!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks Bill, great post. What about inflation in Argentina, though? Maybe you’ve written about it already?

Bill, a few people have already gotten themselves an idea, one they think will indicate that defaulting is not a good idea. They have decided to go to court. In the US, some companies are suing Argentina. And in April, the UK and the Netherlands decided to sue Iceland over its defaults. Although I am not expert in international law, I fail to see how these suits, especially the US ones, can be enforced if the plaintiffs win.

The April event I mentioned took place in 2011.

Dear Larry

Yes. At the time I said that the only way the first world could punish Argentina was by sending the US marines in. Otherwise, sovereignty is just that.

They could sue Greece until the cows come home and would just be wasting money or rather lining the pockets of the silks that would have no hesitation in telling

clients they had a good case.

best wishes

bill

Regarding the suits against Argentina didn´t a court in Ghana seize the Argentine navy flagship because of a lawsuit filed in behalf of a private fund? Does anyone know how that played out?

@Daniel,

Ghana was told by the UN to release the ship because the seizure was illegal.

Bill & Larry:At the time I said that the only way the first world could punish Argentina was by sending the US marines in. Yes, and one of the solidest claims that the USA has to international morality, something usually honored in the breach, is that it made such actions flatly illegal in the UN Charter. (Written by an obscure, forgotten Russian- American economist, more than anyone else, by the way.)

Daniel: The ship was eventually released. Too tired to link to the details.

Some guy,

Are you by any chance thinking of Leo Pasvolsky who married a woman from Pittsburgh, PA? (Sorry, just had to get that in.) He was involved with the UN charter, wasn’t he, while working with Cordell Hull?

Hi Bill,

thanks for the post and for the whole blog.

Refering to the today’s post I think, all this debat about get out or not to the eurozone is a pollitical matter at the end (I’m from spain and this debat is very alive currently). I mean, to get a country out of the euro zone and them default the debt, and by extension, don’t do neoliberal politics and most probably, produce the bankrupt of the german and french bank (as they get the PIIGS’s public debt at the end), so for that, it would be necessary a left wing goverment. At the same time, if the left ocuppies the goverments of the euro zone and they get the political will to shift the sort of political, at the end, it would be the same good result for the entire euroland than for one isolate country.

As always in political economy, the matter is on the polical side.

Just for finish, I think you may relax a little bit the effect of an greek exit. For Argentina it was an escape for its situation, but it was not bed of roses. Not only in the short term, also in the long term, for exemple, Argentina now is much more agrarian than before (with the consecuence of less job creation)

thanks

ayoze

Once again an excellent blog, thank you sir.

Cheers !

Larry: Yes.

Off topic: In today’s AFR, “Professor McKibbin said the Reserve Bank would probably cut interest rates again this year, though his personal view was they should not and that the government should cut spending instead.”

Seems crazy to me.

Excellent post. I write these lines from Argentina just to say to the author that he is right about my country´s situation (ex ante and ex post crisis).

I think it´s better to find a way to solve external debt problems by sharing efforts (esfuerzo compartido): if I win you win, but if I lose you can´t win. Otherwise the “bankers” should admit that they only want to win no matter what.

Good luck to Greek people!

Thanks to “One top”, whose commentary in The Guardian brought me here.

Hi Bill

Are you able to explain what has gone wrong here – Argentina peso in freefall? http://www.smh.com.au/business/day-of-reckoning-looms-as-argentine-peso-in-freefall-20140124-31dt2.html

thanks Janet

Dear Janet Burstall (at 2014/01/26 at 11:45)

Once I finish my current book project (which is occupying a lot of my time) I will write an updated blog about Argentina.

You will note from the article, which is appallingly written, that they claim the main problem is that foreign reserves are declining due to export price falls. This is making it hard to repay negotiated loans in foreign currency units (all US dollars I suspect).

The problem is that the government should never have renegotiated those loans. Once they defaulted they should have stayed that way.

best wishes

bill

Bill!! This is important. Found a paper that argued that the Job Gurantee will not stabilize prices and that it would inferior in doing so against other proposals. Take a look at this and please respond.