I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Okun’s Law survives 50 years – trouble for the neo-liberals

The IMF recently released an interesting Working Paper – Okun’s Law: Fit at 50? – which considers the relationship between the unemployment rate and real GDP growth. I mentioned Arthur Okun in yesterday’s blog. The paper is useful because it debunks a lot of recent research from mainstream economists which claimed that real GDP growth did not bring unemployment down (or not by much). The arguments were then part of the general attack on fiscal activism. The IMF paper finds that the output gaps created by the GFC in the US were so large, that the recovery had to be stronger than usual to eat into the massive buildup in unemployment. The fact that the output gaps have persisted well into the recovery means that fiscal policy has not been aggressive enough in the US. The large output gap that the GFC created needed a very large fiscal response.The bottom line is that shifts in the unemployment is driven by changes output (with the other cyclical adjustments noted above which mediate this relationship). Not a lot has changed – spending equals income which drives employment growth and leads to reductions in unemployment. The neo-liberals can deny that until the cows come homebut those of us who read understand the evidence know they are lying. The message just needs to spread.

Okun’s Law is a rule of thumb that allows us to quickly estimate how much unemployment will change for each percentage change in real GDP growth.

A rule of thumb in economics is not a rigid exact relationship. There are no such relationships in social sciences. It is rather a recognition that labour market and product market aggregates are intrinsically linked by construction and behaviour and over time allow us to make guesses about the future of one variable based on the evolution (hypothesised) of other variables.

The great American economist Arthur Okun left some very useful concepts indelibly etched on those who appreciated his work. He was the chairperson of the Council of Economic Advisors at one point.

I should add he was a mainstream economist who supported Keynesian demand-stimulus policy when unemployment was high. He also brought a very applied bent to the profession and had a good feel for the underlying statistics and interrelationships between them. He taught me a lot when I was a young academic and student.

One such concept was his rule of thumb about the way unemployment reacts to growth. He developed what has become known as Okun’s Law arithmetic to estimate the deficiency in GDP growth which leads to rising unemployment rates. Okun’s Law (it was in fact a statistically estimated relationship with stochastic variation) is the relationship that links the percentage deviation in real GDP growth from potential to the percentage change in the unemployment rate.

His rule of thumb (the Okun Coefficient) said that for every 2.5 to 3.0 percentage point increase in real GNP, the unemployment rate will drop by 1 per cent.

The actual law was developed in terms of the output gap (difference between actual and potential GDP) so that we can quickly estimate what is likely to be the change in the unemployment rate if we know what the change in the output gap is.

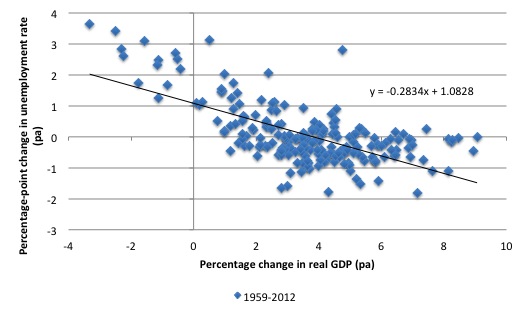

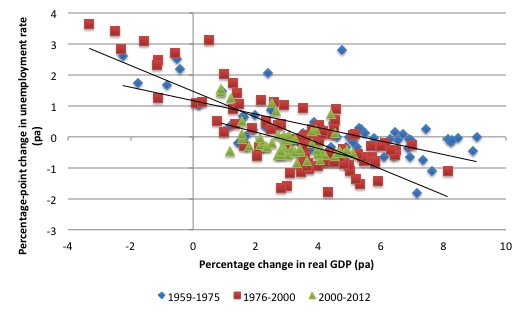

The following graphs are for Australia and show the relationship, first for the full sample of available quarterly ABS data (1959Q3 to 2012Q3), and second, for that period split into three sub-periods: (a) up to 1975, which was the period of true full employment where the government actively used fiscal and monetary policy to ensure there were enough jobs; (b) the period between 1975 and 2000, which marked the two major recessions and their aftermaths and the gathering policy dominance of neo-liberalism; and (c) the period after 2000 which was marked by the total acceptance of both sides of politics of neo-liberalism, supply-side activism and the abandonment of full employment as a policy objective

The full sample suggests an Australian Okun Coefficient consistent with that found in the US. There are not many outliers from the linear regression line, although I wouldn’t for a moment suggest that the relationship is satisfactorily modelled using linear OLS regression. In my own academic work alone and with others much more sophisticated techniques including asymmetric modelling has been the norm.

But it is a rule of thumb after all and approximation is also the norm. The interesting visual fact you pick up from the graph is that the unemployment rate is constant when annual real GDP growth is around 3.9 per cent (where the trend line cuts the horizontal axis).

As I have discussed before, another rule of thumb can be derived from Okun’s Law which brings into play other labour force and production aggregates. This rule of thumb says that if the unemployment rate is to remain constant, the rate of real output growth must equal the rate of growth in the labour force plus the growth rate in labour productivity.

Remember that labour productivity growth reduces the need for labour for a given real GDP growth rate while labour force growth adds workers that have to be accommodated for by the real GDP growth (for a given productivity growth rate).

It is an approximate relationship because cyclical movements in labour productivity (changes in hoarding) and the labour force participation rates can modify the relationships in the short-run. But it should provide reasonable estimates of what will happen once all the cyclically-sensitive components of the economy return to more usual values. I will come back to the cyclical aspects of Okun’s Law.

But the 3.9 per cent implies that the sum of labour force growth and productivity growth would have been about 3.9 per cent in the full employment period. With labour force growth running at around 1.8 per cent per annum (it has slowed a bit recently) this means that steady-state productivity growth was running around 2.1-2.2 per cent, that is, fairly robust for an advanced nation.

Breaking the full-sample down is interesting and of-course the temporal demarcation is always arbitrary and one should be careful not to deduce much from the splits. The more formal way in which to split samples is to conduct stability tests across the break points which then allows one to conclude whether the segments are statistically different or not. We don’t have to do that here – it is a blog after all.

After 1975 the slope steepened somewhat suggesting that for a given change in real GDP growth, the unemployment rate would change by a greater amount than previously, although the difference is not that large. The slope flattened again in the more recent sample.

But the interesting point is that as time has passed the real GDP growth necessary to hold the unemployment rate constant has progressively fallen, which might appear to be a good thing. But the most likely reason is that productivity growth has fallen over time, which indeed attenuates any rise in unemployment resulting from a widening output gap but doesn’t augur well for our long-term well-being.

After all, productivity growth is the only way in which our real (material) living standards can rise.

Researchers were interested in understanding why the Okun coefficient was 2.5 to 3 rather than lower? You can also think of Okun’s Law in reverse. If the unemployment rate fell by 1 per cent then it would suggest that real GDP would rise by 2.5 to 3 per cent.

Why would production rise by that much?

Arthur Okun coined the term “The Tip of the Iceberg” in relation to describing unemployment. The costs of recession and the resulting persistent unemployment extend well beyond the loss of jobs. Productivity is lower, participation rates are lower, the quality of work suffers and real wages typically fall.

To substantiate that, Okun outlined his upgrading hypothesis (in the 1960s and 1970s) and the related high-pressure economy model, which provided a coherent rationale for Keynesian demand-stimulus policy positions. Two references are Okun, A.M. (1973) ‘Upward Mobility in a High-Pressure Economy’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1: 207-252 and Okun, A.M. (1983) Economics for Policymaking, Cambridge, MIT Press.

Okun (1983: 171) believed that:

… unemployment was merely the tip of the iceberg that forms in a cold economy. The difference between unemployment rates of 5 percent and 4 percent extends far beyond the creation of jobs for 1 percent of the labor force. The submerged part of the iceberg includes (a) additional jobs for people who do not actively seek work in a slack labor market but nonetheless take jobs when they become available; (b) a longer workweek reflecting less part-time and more overtime employment; and (c) extra productivity – more output per man-hour – from fuller and more efficient use of labor and capital.

The positive side of this thinking is that disadvantaged groups in the economy were considered to achieve upward mobility as a result of higher economic activity. These cyclical boosts beyond the extra jobs that would be forthcoming were the reason the Okun Coefficient was so high.

The saying that was attached to this line of reasoning was “all boats (large or small) rise on the high tide”.

Okun’s (1973) results are summarised as follows:

- The most cyclically sensitive industries have large employment gaps, and were dominated by prime-age males, offered high-paying jobs, offered other remuneration characteristics (fringes) which encouraged long-term attachments between employers and employees, and displayed above-average output per person hour.

- In demographic terms, when the employment gap is closed in aggregate, prime-age males exit low-paying industries and take jobs in other higher paying sectors and their jobs are taken mainly by young people.

- In the advantaged industries, adult males gain large numbers of jobs but less than would occur if the demographic composition of industry employment remained unchanged following the gap closure. As a consequence, other demographic groups enter these ‘good’ jobs.

- The demographic composition of industry employment is cyclically sensitive. The shift effects are in total estimated (in 1970) to be of the same magnitude as the scale effects (the proportional increases in employment across demographic groups assuming constant shares). This indicates that a large number of labour market changes (the shifts) are generally of the ladder climbing type within demographic groups from low-pay to higher-pay industries.

The evidence is that when the economy is maintained at high levels of employment, workers in low paying sectors (or occupations) also receive income boosts because employers seeking to meet their strong labour demand offer employment and training opportunities to the most disadvantaged in the population. If the economy falters, these groups are the most severely hit in terms of lost income opportunities.

Upgrading also focuses on the mapping of different demographic groups into good and bad jobs. The groups who experience the greatest relative employment gains when economic activity is high are those who are stuck in the secondary labour market, typically, teenagers and women.

While these groups are proportionately favoured by the employment growth, the industries with the largest relative employment growth are typically high-wage and high-productivity and employ mostly prime-age males. Expansion is therefore equated with ladder climbing whereby males in low-pay jobs (as a result of downgrading in the recession) climb into better jobs and make space for disadvantaged workers to resume employment in their usual sectors. In addition, favourable share effects in predominantly male industries provide better jobs for teenagers and women.

So there are many benefits from growth which spread out across rising participation, rising wages, rising hours of work, rising employment and falling unemployment.

But the downside is that the iceberg takes a long time to melt if (a) it is large; and (b) if the recovery is not robust enough. Recovery alone is not sufficient. Real GDP growth has to be consistently strong for some years before the iceberg melts and the upgrading bonuses accrue.

The other side of this is that the longer the recession persists the more the damage penetrates the future.

It is also clear that the unemployment rate behaves asymmetrically with respect to the business cycle which means that it jumps up quickly but takes a long time to fall again.

The impacts of the persistently high unemployment that will remain for years to come will not only impoverish those directly involved but also is setting up the conditions for intergenerational disadvantage. The extant research is clear – children who grow up in jobless homes inherit the disadvantages of their parents. They suffer poor work histories and transit between one poorly paid job after another interspersed with lengthy periods of unemployment.

Once growth returns, it takes a long time to reduce unemployment because labour force growth is on-going and labour productivity picks up in the recovery phase. A nation needs to enjoy very strong GDP growth at first to absorb the pool of idle labour created during the recession.

That is, in the absence of a Job Guarantee.

So there are huge advantages for workers in maintaining the economy at full employment.

Expansion is therefore equated with ladder climbing whereby males in low-pay jobs (as a result of downgrading in the recession) climb into better jobs and make space for disadvantaged workers to resume employment in their usual sectors. In addition, favourable share effects in predominantly male industries provide better jobs for teenagers and women.

Fiscal austerity approaches that deliberately maintain low pressure in the economy and stop the tide from rising thus impose substantial costs that go well beyond those that we can easily see in terms of official unemployment.

The imperative for governments should always be to maintain full employment and limit departures from that state. There are no greater economic losses that a society can occur than mass unemployment.

The IMF paper is interesting because it examines the idea that Okun’s Law is dead (that is, not a reliable rule of thumb). It has been particulary important for neo-liberal orientated economists to claim the relationship is inflated because they advocate fiscal austerity and want to claim the real effects on both real GDP growth and unemployment are small.

So if they can convince people that each of the relationships – fiscal policy impacting on real GDP growth; and a decline in real GDP growth pushing up unemployment – are insignificant then it becomes easier for them to argue for significant cuts in public net spending.

The reality is that these characters are rarely worried about unemployment (unless it threatens their jobs) and real GDP growth (unless it impacts on their prosperity) but are obsessed with cutting public spending (unless it is spending that benefits them).

In the latter case, the expenditure cuts they target are mostly those which benefit the most disadvantaged people in society so these well-heeled economists, fresh from the Chardonnay at lunch-time, feel no threat when they tell journalists etc that major cuts are required.

The IMF paper says that:

These claims matter for the interpretation of unemployment movements and for macro policy. Okun’s Law is a part of textbook models in which shifts in aggregate demand cause changes in output, which in turn lead firms to hire and fire workers. In these models, when unemployment is high, it can be reduced through demand stimulus. Skeptics of Okun’s Law question this policy view … [some argue] … that Okun’s Law has broken down because of problems in the labor market, such as mismatch between workers and jobs. They stress labor market policies such as job training, not demand stimulus, as the key to reducing unemployment.

So the relentless revision of history and challenge to anything that justifies the obvious – that spending equals income and output, which stimulates employment growth. And the second obvious point – government spending is no different – in that respect.

The IMF paper thus:

… asks how well Okun’s Law explains short-run unemployment movements. We examine data for the United States since 1948 and for twenty advanced countries since 1980. Our principal conclusion is that Okun’s Law is a strong and stable relationship in most countries. Deviations from Okun’s Law occur, but they are usually modest in size and short- lived. Overall, the data are consistent with traditional models in which fluctuations in unemployment are caused by shifts in aggregate demand.

Which should be the end of the argument really.

The main results of the IMF paper are that:

1. They find that “a linear Okun’s Law fits the data well”. They “find no evidence of non-linearity”. This is interesting because in my own work (with Joan Muysken) we estimated an asymmetrical Okun-type model after using a grid search to detect the rate of real GDP growth that triggers the asymmetry in its impact on the labour market.

We found that the best demarcation occurs between positive and negative real GDP growth rates, which means in English that the Okun coefficient is different when real GDP growth is falling compared to when it is rising. The reason being that the hysteresis and asymmetry in unemployment (which we found in an earlier paper) are driven by output shocks.

Papers subsequently published but available for free in working paper form which expand on this if you are interested are:

2. The IMF paper found “no evidence against our simple specification with a constant Okun coefficient”, which means they could not detect any temporal instability – the coefficient is constant over time.

3. In comparison to “Okun’s 50-year old specification” they find:

The absolute values of Okun’s estimates are close to 0.3; inverting this coefficient, he posited the rule of thumb that a one point change in the unemployment rate occurs when output changes by three percent. Our coefficient estimates, by contrast, are around -0.4 or -0.5. These estimates fit roughly with modern textbooks, which report an inverted coefficient of two.

The reasons relate to econometric specification of the models used, which I won’t go into here (it relates to lag structures in the time series models).

How does this relate to the “jobless recovery” argument that is current at present in the US? If economic recoveries are “jobless” then it would suggest that Okun’s Law is no longer valid – it “Law has broken down in a particular way … [with] … weaker employment growth and higher unemployment than Okun’s Law predicts”.

The IMF paper “found no evidence of a breakdown in Okun’s Law”.

To demonstrate they produce this graph, which shows the movement in the actual unemployment rate from the 1940s to the present day and the “fitted values” (predicted values) from an Okun’s Law equation. This is really a stunning validation of the predictive capacity of the Okun relation and should shut those up who keep wanting to run the neo-liberal line. Courtesy of IMF research at that!!

The IMF authors describe this graph accordingly:

As Figure 5 shows, the path of U.S. unemployment consistently fits the predictions of Okun’s Law, and recent recovery periods are no exception. This finding raises a puzzle: why do so many observers think that something in the employment-output relationship has changed?

The way in which the authors explain that apparent puzzle is as follows:

Okun’s Law is a relationship between deviations of unemployment and output from their long-run levels. Since a large output gap has persisted, Okun’s Law predicts large deviations of employment and unemployment from their long-run levels. From 2009 through 2011, the output gap … averaged -10.8 percent and the unemployment gap averaged 4.4 percentage points. The ratio of the two gaps, -0.41, is close to our earlier estimates of the Okun coefficient.

The fact that “sizable output gaps persisted well into the recovery” means that fiscal policy has not been aggressive enough in the US. The large output gap that the GFC created needed a very large fiscal response.

But the President and the Congress were cowed by irrational attacks on the effectiveness of government deficits in promoting growth. A great many commentators and economists should be charged with malpractice for lying about that.

The US government backed off its stimulus far too early which has allowed the output gap to persist and the higher unemployment to persist. There has been growth but not robust enough. The Government needed to create a growth overshoot (that is, well above trend) to quickly eat into the output gap.

I will leave it to you to read the rest of the paper if you are interested. It goes on to analysis country-by-country results etc.

Conclusion

This is one IMF paper that is well-grounded and well-constructed. It pursues a viable methodology and has produced very interesting results.

The bottom line is that shifts in the unemployment is driven by changes output (with the other cyclical adjustments noted above which mediate this relationship).

Underpinning the shift from fiscal activism is a belief, held by many economists, that a unique (natural) level of economic activity exists (the so-called NAIRU) which is consistent with low inflation.

Policy makers constrain their economies to achieve this (assumed) cyclically invariant benchmark. The NAIRU is not observed and a range of techniques are used to estimate it. Yet, despite its centrality to policy, the NAIRU evades accurate estimation and the case for uniqueness and cyclical invariance is weak.

The IMF research supports the view that cyclical factors are dominant in explaining the shift of the any of the “steady-state” unemployment estimates (that is, the NAIRU).

Given these vagaries, the use of the NAIRU as a policy tool is zero!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This post might be of interest http://nakedkeynesianism.blogspot.com/2012/08/okuns-law-is-doing-fine.html and also this paper which deals with the relation of Okun and Kaldor-Verdoorn https://www.econstor.eu/dspace/bitstream/10419/64450/1/572641087.pdf (published in the RRPE in 2008).

Excellent stuff, as always. As civil servant, I don’t know whether to be happy or sad with this research — I am forced to couch policy suggestions in terms of supposed skills shortages etc., when I know that’s all bunk. The problem is not the hypocrisy, per se, as that is the bargain you make when you join the public service, but the difficulty many civil servants have with living with the contradiction — the easiest, least stressful path, is simply to give way and accept/internalize neo-liberal ideology.

The above link to the IMF working paper “Okun’s Law: Fit at 50?” is: https://billmitchell.org/blog/www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1310.pdf

shouldn’t it be just

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1310.pdf

Dear Constant

Thanks for the correction. I had left off the http:// part of the address.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

My secondary school Economics teacher used to recommend your work (he too was Australian). I’ve been following your blog for a while now and I appreciate what you have done. As I finish up my undergraduate studies in economics in the US, I am surprised to see how much of what I learnt in secondary school seems to have been forgotten in the public discussion surrounding economics.

Okun’s law is a great example. I always cringe when I hear the “expansionary austerity” argument being trotted out in Europe and on the American right. It seems that we had figured this stuff out a long time ago. Hell, Okun’s law is something I have been aware of from my NSW HSC days…