I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Government budgets bear no relation to household budgets

Today (December 19, 2012), the economics editor for the Sydney Morning Herald (Ross Gittins) wrote an Op Ed piece – It’s the weak recovery that worries, not surplus – which urged his readers to reorient their thinking about the Federal government’s obsession with achieving a budget surplus in the coming year. In that sense, it was welcome article from an influential journalist. But closer reading demonstrates that the writer is straddling the line between comprehension and myth-perpetuation. Many readers have asked me to pin-point the strengths and weaknesses of the article for their own edification. So lets proceed. The key point is that the budgets of currency-issuing national governments bear no relation to household budgets. If we do not jettison that myth then very little progress can be made on the more complex parts of the narrative that leads to the conclusion that such a government can never run out of money and all the negative consequences that are alleged to necessarily follow the use of budget deficits (higher interest rates, inflation, eventual insolvency) are lies, which aim to perpetuate a dominant paradigm rather than advance the welfare of all of us.

The article started off in a good way by concluding that “the saga of whether the Gillard government will manage to get its budget into surplus this financial year has reached farcical proportions”.

We learned earlier this months (exactly two weeks ago) that the real GDP growth rate had “slowed to 0.5 per cent in the three months to September”. As Ross Gittins points out the media scrum:

… concluded the most significant implication of this news was that it increased the likelihood of the budget balance not returning to surplus (which it does) I realised the public debate was running off the rails.

It is the same as the media highlighting the views of bank economists about interest rates probabilities when the ABS has just released a monthly labour force result that tell us that employment growth is dead, unemployment is rising and participation is falling. A false sense of priorities. One can understand why the bank economists are obsessed with interest rates. But why should a national media that should be increasing awareness across the nation only serve the interests of one small, relatively unimportant sector.

Ross Gittins, very correctly notes that:

Contrary to the impression we are being given, the budget balance is a means to an end, not an end in itself. We don’t run the economy to balance the federal government’s budget. And when we get our quarterly report on how the economy’s travelling, the primary question is not what it tells us about the government’s performance or it political prospects.

The budget was made to serve the economy, not the other way round. And the economy was made to serve us. So the primary question to be asked when we receive the quarterly report card is what it implies for us. Is our material standard of living improving more slowly than we’d prefer? Is inflation getting worse? Is the economy growing fast enough to stop unemployment rising?

The neo-liberal period has been characterised by the elevation of the irrelevant (public financial ratios) and the downplaying of the most important (unemployment and underemployment).

We are led to believe that if the Deficit to GDP ratio rises from 2 to 4 per cent then there is impending doom whereas not much attention is given to rates of teenage labour underutilisation around 38 per cent or overall rates of labour underutilisation of 12.5 per cent. The lost income every day from that scale of labour wastage seriously undermines the material standards of living of the nation.

There is nothing unambiguous that can be said about a Deficit to GDP ratio rising from 2 to 4 per cent. A deficit outcome is just a reflection of what is happening in the areas of the economy that matter.

Ross Gittins correctly says:

Politically, the only thing people think they need to know is that anything called a deficit must be bad and anything called a surplus must be good. Most political reporting about the budget balance is based on this assumption.

This simplistic (and largely erroneous) dichotomy has driven political debate in the nation and led to the Government claiming surpluses are virtuous. As Ross Gittins notes the Government has now “elevated … [the achievement of a surplus] … to the status of a solemn promise. We hear the Treasurer saying that they will achieve a surplus at all costs.

They never mention the costs of-course. Which are – lost national income, higher unemployment and underemployment, stagnant real wages growth. All the things that really determine our material well-being.

It has become so bad that when the economy slows (as a result of their withdrawal of public demand) and the tax revenue falls (via the automatic stabilisers), the Treasurer then calls an emergency budget meeting, which comes up with even more public spending cuts to keep the pursuit of the surplus on track! It is that moronic. The dog chasing its tail. Meanwhile the economy stalls and the disadvantaged go further backwards.

As Ross Gittins notes:

Economically, however, it ain’t that simple. From an economic perspective, budget deficits are bad in some circumstances, but good in others. Similarly, budget surpluses are good in some circumstances but bad in others.

Now my version of that essential truth is that a good deficit is one that is associated with full employment and a bad deficit is one that is associated with high unemployment. So a nation could be running a Deficit to GDP ratio of 5 per cent and in some cases it would be good and other cases bad.

The former case (good deficit) would exist if the government was ensuring that the non-government spending gap (the desire to save overall) was filled up to 5 per cent of GDP and thus ensuring that aggregate demand was sufficient to maintain full employment.

The latter case (bad deficit) would be the result of a deficit being too low in the first instance to cover the non-government spending gap with the result that the economy moves into recession, unemployment rises, and the automatic stabilisers (lower tax revenue and rising welfare spending) force the budget deficit upwards to 5 per cent.

A similar case can be made to distinguish a good and bad surplus.

The common element? The fact that we are not concerned at all with the budget “number”. Our concern is with full employment and other broader social goals that are dependent on national income growth and the budget outcome should be whatever is necessary to achieve those goals.

The other variables are, of-course, the spending and saving decisions of the external sector and the private domestic sector. We understand that the budget outcome is largely beyond the control of the government anyway. If the external sector is strong, then the budget might be in surplus and the aggregate demand growth sufficient to maintain full employment. That would be a good outcome because the real aims are being achieved. Equally, such a situation might need a large budget deficit, if the private domestic sector wanted to save more overall out of their income.

It all depends. Which means that any government that defines its primary fiscal policy goal in terms of some given fiscal outcome (deficit) is irresponsible and setting itself up for a beating.

That is all the more relevant when the fiscal policy goals outlined is a surplus at a time that the non-government sector is unwilling to drive aggregate demand at rates sufficient to generate full employment. Then the fiscal goal is nonsensical and equivalent to deliberate vandalism.

How does Ross Gittins explain the point? He writes:

… national government budgets operate at two quite different levels. At one level the government’s budget is the same as that for a business or a household: it’s a forecast of how much money will be coming in and going out during a year. You use budgets to ensure things go to plan and you don’t get in deeper than you can handle.

At another level, however, the budgets of national governments are quite different from other budgets. Because they’re so big relative to the size of the economy – equivalent to about a quarter – what’s happening to the economy has a big effect on the budget. But the budget is so big it can also be used to affect what happens to the economy.

First, it is very damaging in relation to the edification of the public to consider the budget outcome of a currency-issuing government to be equivalent at any level to the currency-using household budget. While the accounting analogy holds ($s in and out) that serves only to confuse.

For example, revenue to a household gives it increased purchasing power. Revenue to a currency-issuing government provides it with no increase in its capacity to spend. That is a fundamental difference.

Similarly, the meaning of a surplus is vastly different in the two cases. A surplus for a household means it is saving. Saving for a currency user is an act of foregoing consumption now to enhance future consumption and is driven by what economists call time preference and yields on saved funds.

There is no such meaning that can be given to a public surplus. The government does not need to stockpile financial assets in its own currency in order to spend tomorrow. The capacity to spend in its own currency is not dependent or contingent on its current or past budget position. It is only dependent on there being goods and services available for sale in the currency it issues.

Those two examples demonstrate why thinking of public budgets as “big” private budgets is erroneous and only serves to perpetuate the very myths that Ross Gittins is railing against.

He went on (read as the continuation of the previous quote):

This is something few non-economists seem to understand. People who focus solely on the political implications of the budget, assume that if the budget moves from surplus to deficit this could only be because the government has chosen to spend more than it is raising in taxes. If the budget moves from deficit to surplus, this could only be because the government has chosen to spend less than it’s raising in taxes.

This point is correct. The statement is merely pointing at that the budget outcome is the sum of discretionary spending and tax decisions and the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector (that is, the state of the economic cycle).

A particular budget outcome, as explained above, tells us nothing unambiguous about the intentions of the government.

As Ross Gittins correctly notes budgets can “go from surplus to deficit … when the economy turns down” and he might have added – without the government changing any of the fiscal parameters.

He also notes that the endogeneity of the budget balance (its dependence on the state of the economic cycle quite apart from the discretionary decisions of government) means that “just as the budget balance deteriorates automatically when the economy turns down, so it improves automatically when the economy recovers and resumes its growth”.

That means that it is stupid to subjugate our concerns about the state of the economic cycle (and the real things that are implied by that such as unemployment) to an obsessive focus on a particular budget outcome (which the government cannot control anyway).

He is correct in imploring us to worry about “the weak recovery” rather than “delayed return to surplus”.

As a general rule, we should never be worried about a given budget outcome in isolation from the circumstances that create it. It is the latter that should be the focus of policy not the former.

So you can see that this article is pushing in the right direction. It nearly gets it. But then at a critical juncture in the narrative, Ross Gittins crosses the line back into mainstream (erroneous) land and thereby confuses the issue and undermines the intent of his article.

Juxtapose the way Ross Gittins writes with the December 2012 White Paper from the Senior Economist (Tanweer Akram) at ING Investment Management – The Economics of Japan’s Lost Decades.

This paper aim is to:

… examine the economic causes and consequences of Japan’s lost decades … and offer a number of policy recommendations to lift the country from its funk …

It concludes that “(g)iven’s (sic) its history of comebacks, we’ve no reason to believe Japan cannot overcome its current economic stagnation and regain its rightful place in the global economy, spurred by appropriate economic, fiscal and monetary policy”.

So an interesting topic. Japan is a classic real-world demonstration of the precepts of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) in action. For two decades, it has sustained very high (relative) deficits, experienced escalating public debt ratios (now more than 3 times the so-called insolvency threshold of 80 per cent), has maintained stable interest rates around zero and government bold yields close to zero; and has fought deflation rather than inflation.

Despite a monumental property market crash in the early 1990s, it has also largely avoided a major recession and spiralling unemployment. Outside of the 2008 real GDP dive (it lost “35 per cent peak to trough” and the decline was “must steeper … than those seen in the U.S. and the euro zone) and the further decline as a result of the “2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami”), it has endured a subdued real GDP growth environment.

In 2008, the “decline in net exports was the main driver of the sharp slowdown in economic activity in Japan”. This is because “(a)dvanced manufacturing accounts

for a larger share of economic activity and production in Japan compared to other major advanced capitalist countries, and exports of these goods remain considerably below their peaks.”

But considering the asset losses the nation endured in the early 1990s, its “lost decade” outcomes still put the economic performance of many nations to shame. The ING Report notes that:

Even though the Japanese economy has been mired in subdued growth and deflation for decades, the quality of life in the country remains high … Japan is ranked 12th in human development according to the United Nations … Human Development Index … Life expectancy in Japan is the highest among G-7 countries, while its infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births – a revealing indicator of health outcomes – is quite low. Both crime rates … and incarceration rates are also low …

So when a mainstream economists mouths off about the inevitability of high interest rates and rising deficits, or rising inflation, and insolvency and all the rest of the predictions that come out of the mainstream macroeconomics literature the most simple retort is – please explain the Japanese experience.

All sorts of ad hoc arguments are presented as an attempt to present Japan as a “special case” or an anomaly of some sort or another. The fact is that none of these arguments have traction.

Japan is a currency-issuing nation which floats its currency on world markets. It also chooses its own interest rates. It is not different to any nation that has designed its monetary system in that way.

The ING Report makes some interesting points – and I am only focusing on the public sector fiscal and monetary policy issues. Its explanation of the “lost decades” is interesting and informative but largely descriptive and broadly accepted.

The paper also documents the demographic trends – its declining fertility rates and the rapidly ageing society (with commensurate increases in the dependency ratios); declining labour force participation; and an upward drift (though modest) in the unemployment rate.

Its notes that real wages growth has been stagnant as the economy has become even more open (demonstrated by the increase in “the ratio of the sum of real exports and real imports to real GDP) and this has reduced the growth in private consumption.

The suppression of domestic demand growth has also stifled private capital formation (firms do not want to invest if the growth in demand is slow) but the main reason that “the share of investment in real GDP has decreased” is “due to the decline of public investment”. In other words, concerns over the size of the deficits has led to a suppression of aggregate demand growth in the form of public infrastructure formation.

The really interesting part of the analysis starts on Page 16 when the Report considers the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy over the last two decades.

It notes the rise in deficits (as a percent of GDP) and says that the “ratio of general government net debt to nominal GDP is the highest among G-7 countries … and is noticeably higher than other advanced countries”.

The “large deficits are the result of automatic stabilizers and fiscal stimulus”, which “have prevented a depression and a collapse in economic activity”, they have not been sufficiently large enough to “overcome the country’s stagnation”.

Why? The conjecture is that public spending “is often politically directed”, which tells us that the design of fiscal policy interventions matter. But the Report also stresses that the decline in public investment has also undermined the overall capacity of fiscal policy to stimulate faster rates of growth.

But still, with such large relative deficits why haven’t bond yields risen?

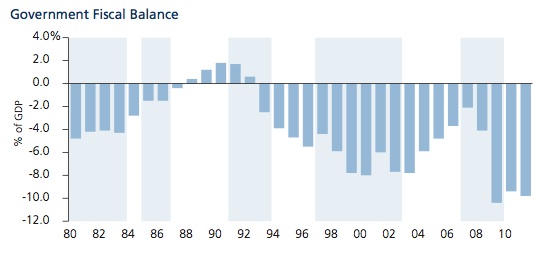

The following graphs (the top is the Report’s Figure 23 and the bottom Figure 25) show, in turn, the history of the budget deficit since 1990 and the 2- and 10-year bond yields since the collapse in 1991. All macroeconomics students should be asked to explain these two graphs. Most would fail or be so confounded they could not write a word.

They have been taught that when deficits rise, the government has to issue more debt which floods the market and pushes down the price that traders are will to pay for the bonds. That is, the yields they demand are elevated.

They have also been taught that bond yields reflect general interest rates and when the government is running deficits it competes in the private capital markets for scarce savings and this competition pushes up interest rates generally.

The higher the deficits the more accelerated the interest rate rise will be.

That is the mantra these students recite back to professors as part of their examination process.

These juxtaposed trends negate everything that the mainstream macroeconomics textbooks (erroneously) teach them. MMT proponents have always argued that budget deficits do not push up interest rates as a matter of course. That there is no such thing as a finite pool of saving that is fought over. We know that when saving is a function of income and as real GDP and national income grows so do savings. We also know that banks create deposits when they make loans. There is no question that they have to attract savings in advance and then access their vaults to make the loans.

So how does the ING Report explain the non-relationship between the deficits and the bond yields?:

Contrary to the conventional wisdom – for example, the International Monetary Fund, credit rating agencies and so forth – Japanese government bond yields have stayed low even as the country’s fiscal deficits remained elevated and the government’s net debt ratio rose. The reasons are simple: 1) Japan’s debt is issued in its own currency, 2) the Bank of Japan can control government bond yields though its balance sheet and communication tools, and 3) the demand for government debt remains strong, as the country’s domestic private financial institutions hold the bulk of it.

The fear that bond market vigilantes or increased levels of government debt would cause Japanese government bonds to sell off suddenly and yields to spike sharply have proven to be spurious. In countries with sovereign currencies such as Japan, changes in long-term interest rates are fairly tightly correlated with changes in short-term interest rates; thus, long-term interest rates generally stay low when short-term interest rates are low.

The principle features of a sovereign nation – issues its own currency and sets its own interest rates which condition the term structure of interest rates including bond yields.

But there is more. The ING Report notes that the international credit ratings agencies have “downgraded Japan’s government debt many times since the late 1990s” but the evidence shows that these downgrades “have had no effect on yields”.

There goes another myth. The game we hear played out in the media where a mainstream macroeconomist is wheeled out and asked about the build-up of public debt and responds with reference to some talk about a pending “loss of AAA rating” causing a “lack of confidence in bond markets” and “the path to financial insolvency”. Anytime you hear that sort of interview you can conclude the commentator knows zip about the topic they are purporting to be an expert in. Zip = Zip.

Why are the rating agencies irrelevant with respect to government bond yields?

The ING Report says that:

The rating agencies seem unwilling to acknowledge that the credit risk profile of a government that issues debt in its own currency – such as Japan and the U.S. federal government – is very different from the credit risk profile of a government that issues debt in a currency that it does not control – such as the peripheral countries of the euro zone and U.S. state and local governments. Importantly, a central bank issuing bonds in its own currency can keep yields low for as long as it deems appropriate.

The Bank of Japan can and does control – and, indeed, may even target -Japanese government bond yields as appropriate through its overnight policy rates and other balance sheet tools, including large-scale asset purchases. Moreover, given its ability to issue its own currency, the government of Japan retains the ability to always service its yen-denominated debts barring some extremely low-probability but high-impact catastrophe.

There you have some more fundamental MMT. The US or Japan cannot become Greece. The former operate a different monetary system than the latter participates within. The former are sovereign the latter is not and uses a foreign currency and creates liabilities in a currency it doesn’t issue.

These are fundamental points.

So next time, a commentator comes out and says or writes that the US is heading towards a Greek oblivion you can conclude the commentator knows zip about the topic they are purporting to be an expert in. Zip = Zip.

Further, note that central bank “can and does control” the bond yields (if it desires). The bond markets cannot be in charge in sovereign nations if the government chooses to exercise its intrinsic authority.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

So next time, a commentator comes out and says or writes that the bond market are about “to choke of funding” to the US or the UK or Japan unless they get their “deficits under control” you can conclude the commentator knows zip about the topic they are purporting to be an expert in. Zip = Zip.

Which means that a sovereign government can never run out of its own currency. And that means that the qualifying statement in the ING Report about a “low-probability but high-impact catastrophe” could only refer to some voluntary decision by the polity to default. There is not catastrophe that would eliminate the financial capacity of the Japanese government to “service its yen-denominated debts”.

Finally, the paper considers debt-servicing in more detail and rehearses the standard argument that MMT has been making for many years now:

… for any sovereign government that issues debts in its own currency, such as Japan, its debt is merely a promise to deliver more of its own liabilities in the future. That is to say, a Japanese government bond is simply a promise to pay yen – which are merely additional government liabilities that happen to be non-interest bearing – at various future dates. It could perhaps be argued that a higher ratio of public debt to nominal GDP might under certain circumstances lead to inflation and a depreciation of the Japanese yen, but there are no operational barriers to prevent the government of Japan from servicing its debt. As such, Japanese authorities are theoretically free from obsessing about fiscal consolidation, and the country’s fiscal policy should focus on promoting public well-being and economic prosperity.

The Report then turns to monetary policy. Among the insights provided is the following conclusion:

… the expansion of central bank’s balance sheet does not necessarily lead to higher inflation … they do not directly affect bank lending or credit growth, and inflationary pressures may not arise unless credit growth fuels economic activity. This is particularly true when an economy is characterized by excess slack and spare capacity, as Japan’s is.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

The final section of the paper discusses the evolution of the sectoral balances in Japan. This is a standard tool used by MMT to link the financial and real sides of the economy and the analysis presented clearly demonstrates that:

… the change in general government deficits has been the main driver in the variation of domestic private balances. As the domestic private sector deleveraged and spurned debt to repair their balance sheets after the bursting of asset bubbles, the government had to run deficits in order to prevent the economy from failing into a tailspin.

So next time, a commentator comes out and says or writes that the government and the private sector has to reduce their debt levels by running surpluses (especially in the context of nations that are running external deficits) you can conclude the commentator knows zip about the topic they are purporting to be an expert in. Zip = Zip.

Finally (and I am running out of time), the ING Report offers some policy advice. The main conclusion is consistent with what MMT economists have been recommending in the face of major opposition from many mainstream economists include those in the leading multilateral agencies such as the IMF and the OECD.

The ING Report says that:

… the Japanese authorities should prioritize policies that strengthen aggregate demand, while recognizing that efforts to strengthen aggregate supply are secondary in importance. Indeed, increased aggregate supply of inputs and productivity without an ancillary increase in aggregate demand could lower real wages and real income. Meanwhile, Japan should also consider shunning various conventional reform policies and the fiscal consolidation advocated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the International Monetary Fund.

That is a powerful rejection of the mainstream austerity doctrines that are destroying millions of jobs around the world as I type.

How might the Japanese government stimulate aggregate demand:

1. “increase the public investment share of real GDP in order to provide a boost to growth and advance the capacity of its citizens”.

2. “focus on policies that promote labor-intensive aggregate demand, fostering real income growth and real wage growth”.

3. “undertake public investment and public works program to address the needs of its citizenry, aging population and provide public services”.

4. “consider supporting large-scale employment programs – in health care, services for the elderly, environmental protection, disaster relief and reconstruction, education, child care and so on – or job guarantees to provide near-full employment and to help generate real income growth, stabilize real wages and combat deflation”.

Yes you read that correctly. This is a private investment report suggesting that a Job Guarantee is a feasible way to stabilise real wages and combat deflation, while still generating near-full employment.

Moreover, the ING Report rejects the use of “conventional policies aimed at weakening labor protections, reducing workers’ real wages and income are harmful for economic growth, and probably foster an environment that is prone to deflation”.

The justification for these policy recommendations can be found in the superior understanding of the way the monetary system operates and the intrinsic links between the currency-issuing government and the currency-using non-government sector that is demonstrated in this ING Investment Bank “White Paper”.

Conclusion

It suggests that progress is being made when one of the large investment banks is publishing material that has its genus in the principles espoused by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

If only the Sydney Morning Herald senior economics editor would also walk across the line that his current work is clearly straddling.

That is enough for today!

I fully agree with the thrust of Bill’s article. Every treasury in the world should have that famous sentence uttered by Keynes carved into the masonry above its front door: “Look after unemployment, and the budget will look after itself.”

However, some of the ideas put by ING are crass. E.g. “increase the public investment share of real GDP…”. That “share” has sweet nothing to do with stimulus. I.e. if the optimum share is X%, that optimum figure won’t change just because the economy rises by Y% thanks to some stimulus.

“Focus on policies that promote labor-intensive aggregate demand….” Complete rubbish. It would be a bureaucratic nightmare distinguishing between labour intensive and capital intensive industries.

It’s a popular myth that expenditure on labour intensive industries creates more jobs than expenditure on capital intensive ones. Reason is that there is only one ultimate cost: labour. I.e. if you spend money on an expensive machine, labour and machinery are needed to make the machine, and labour and machinery are needed to make the latter machinery and so on, and so on. I.e. spending $Z on a capital intensive industry ultimately creates as many hours of work as $Z spent on a labour intensive one.

Bill – related to the subject of MMT being used by banks I noticed this article last week: http://www.businessinsider.com/goldmans-jan-hatzius-on-sectoral-balances-2012-12

Dear Ralph

You are making a valid point with your assertion that ultimately there is only one cost: labor. However, you are overlooking one important fact: capital can be imported. If, as a result of a stimulus, a company decides to invest more in machinery instead of hiring more labor, then these machines could come from abroad, in which case the labor needed to produce these machines will be foreign labor.

Regards. James

“then these machines could come from abroad, in which case the labor needed to produce these machines will be foreign labor.”

Not sure that’s the case if you’re operating a non-convertible currency.

If you buy a foreign machine with a non-convertible currency you don’t actually buy the foreign machine. What you effectively buy is some exports from your domestic economy (ignoring savings for the moment) with the foreign exchange system intermediating for you.

The real exports from your country are then essentially swapped for real imports from the foreign country.

So you are indirectly buying labour output from your own economy.

And of course in the end there is only one planet. The division into countries and currency areas is arbitrary.

The budget surplus saga has reached “farcical proportions”? It was farcical when it was first uttered way back when. The foreign sector did not support it, the savings vs spending desires of the domestic sector didn’t support it, and the high exchange rate was undermining any hope of rescue by making Austrlalia as a nation more expensive as foreign nations cheapened (and who at least attempted to influence any strengthening in their exchange rates … Here you can blame the RBA for being so far behind the available information, and only now coming to conclusions they should have arrived at many moons ago, and even then with a sense of revelation. Breathtaking!). The data has reflected an increasingly poor real economy ever since the post-GFC bounce petered out in 2009.

The budget “saga” is a measure of the conservative’s spectacular success in poisoning impressionable minds about budget balances, interest rates, amongst other things (anyone say refugees?). It is equally a measure of the insipid response of the Labor Party who were unable to construct a counter-narrative to any of these things, preferring to become a “lite” version rather than an educator. There is a dangerous preoccupation in this country (though we are clearly not alone) on politics as opposed to government and sustainable policy. And so we have both major political parties intent on undermining the country’s prospects by racing toward the nearest or biggest surplus, ignoring the employment prospects of those that are expected to ultimately help alleviate the dependency ratio, and a central bank that doesn’t appear to be able to connect dots. It is unedifying and embarrassing, but mostly appalling.

The ING report is a cracker, and the work of Claudio Borio you have cited on a few occasions now is simply first class.

Aside … I just heard the news anchor say the Queen attended a cabinet meeting in the UK for the first time since 1781 … I didn’t realise she was that old!

“I just heard the news anchor say the Queen attended a cabinet meeting in the UK for the first time since 1781 … I didn’t realise she was that old!”

heh.

The key to that is to realise that The Queen is an office and Elizabeth Windsor is the current office holder.

James and Neil,

In contrast to where a country has a non-convertible currency, if the currency is convertible, then INITIALLY James’s point is valid: that is, stuff bought from abroad creates jobs in some other country. But buying stuff from abroad depresses your currency relative to others which boosts your exports which in turn creates jobs back home (though that could take time to materialise).

Also (to be technical) my point about labour being the only ultimate cost is not quite right. There are actually three ultimate costs aren’t there? Labour is the main one, but there is also economic rent and profit, I think. Though you can count profit as the “labour” of the entrepreneur (to stretch the meaning of the words “labour” and “profit”). But I’ve forgotten some of basic economics text book stuff, so I might be wrong there.

Bill,

What is the MMT position on LTG (Limits To Growth) and biospheric homeostatic boundary problems?

I know you are busy and productive. However, given that this is a blog with provision for replies, I hope you can reply to this question. The reasons for the question are expanded upon a little bit below.

Accepting that MMT is broadly correct, the next key question is the issue of resource and system constraints. I am thinking particularly of Limits To Growth (LTG) and so-called “boundary” problems. It seems to me axiomatic that the human economy is a sub-system of the biosphere. It involves living physical entities (humans), physical flows of energy and materials and must perforce be subject to the laws of physics in general and the Laws of Thermodynamics in particular.

It also seems axiomatic to me that an economy can experience two kinds of brakes, retardations or shocks to its performance. Let us call them “impediments” to economic performance. As well as bad macroeconomic policy (for example an “austerity” surplus during a slowdown) being a prime form of endogenous impediment (taking political economy as a whole), there is the issue of exogenous impediments, namely natural resource shortages and waste disposal/diffusion effects and their knock-on impacts. Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) gets all the press but species extinctions and disruption to the nitrogen and phosphorous cycles are other problems now listed as “boundary” problems as we are pushing or exceeding the safe boundaries of the biosphere’s homeostatic systems.

To reiterate the question and expand it;

(1) What is the MMT position on LTG (Limits To Growth) and biospheric homeostatic boundary problems?

(2) How do MMT theorists view the eventual necessity for a stabilised, steady state population and economy? (This would be stabilised quantitatively speaking as qualitative growth e.g. growth in knowledge and technology could still occur.)

(3) How does this impact on the apparent reliance of even MMT on endless growth?

(4) Does MMT really offer a fundamental advance on all orthodox economics which latter persistently ignores real world limits?

Over a year ago, Bill replied to a similar question from me;

“Bill Mitchell does recognise that (Limits to Growth)”

“Bill’s version of MMT does recognise that.”

However, Bill has never, to my knowledge, posted a single blog article on this topic or posted a link to such an article by himself or other MMT theorists. Bill has consistently declined or omitted to reply how he recognises it and what implications it has for MMT theory.

It’s the kind of brush-off answer one would expect from intellectually dishonest economists like Milton Friedman. Bill is not of that ilk, not by a long chalk. However, I am still waiting for a real answer which respects and addresses the question. If a blog host seeking to promote intelligent debate is not prepared to answer genuine and fundamental questions in detail, he or she cannot expect to garner ongoing informed and committed support for their position.

Further lack of explicit address to the issues of LTG would cause me to lose all interest in MMT as a serious economic-intellectual enquiry. By effectively ignoring and not developing a comprehensive response to the incontrovertible fact that the economy is a sub-system of the biosphere, MMT would become ipso facto a degenerate research program.

Dear ralph and Neil

If the trade account were always in balance, then an increase in imports would indeed be matched with an increase in exports. However, we know that mainly due to cross-border capital flows, there can be trade deficits and surpluses.

As to costs of production, there are only two: labor and non-renewable natural resources. A cost is a resource that is used up in production, not something that is merely used. If I work an hour in a crop field, that’s a cost because that hour of labor can’t be used again. However, the land on which the crop is grown is not a cost as long as its fertility is not depleted. It is being used, not used up. Fossil fuels are also costs of production because they are used up.

Rent is not a cost of production because it isn’t something that is used up. If I let you till a piece of land that own and you in return pay me 25% of your crop as rent, then I haven’t contributed any resource to production. If you kicked me off the land and became the owner yourself, the rent would no longer have to be paid, but production could go on as before.

Regards. James

Ikonoclast

What you are searching for, I believe, is a yet-to-be-realised fusion of MMT and Ecological Economics. MMT itself does not seem to take a position on LTG, beyond the refrain that it is real resources rather than monetary resources that are the true constraint on growth.

MMT is (IMO) certainly wedded to the requirement for continual growth in GDP. Bill has stated this explicitly on a previous blog:”A fully employed sustainable economy will still require real GDP growth rates of say 2-3 per cent (depending on labour productivity and labour force growth). It will still require aggregate demand (spending) to grow.”

I suspect there are hidden assumptions of perpetually decreasing resource intensity embedded in such statements? Otherwise, it conflicts with biospheric reality.

Growth has, over the last half a century or so, been the panacea to salve the wounds of economic inequality. MMT has much to offer in helping to reduce these inequalities, but I hope it can do this without clinging to the outmoded “Growth at all costs” paradigm.

MMT is a monetary theory.

The general message is Get Real.

ie there are enough real constraint issues that need addressing without introducing artificial nominal ones.

What to do with the real constraints are a totally different area of research.

But one thing is for clear – if we have a system where nominal constraints are still seen as constraining then the big real issues are never going to be addressed. To deal with them will take co-ordination along the lines of that which put a man on the moon.

@Ikonoclast

I am a real beginner on this subject and maybe I have it all wrong, but I suggest that MMT describes our economic system as it is now. It can make predictions within the boundaries of that system, but when the changes move outside those boundaries then logic requires that the theories alter to take account of those changes. As specific resources become scarce, their price will rise. I would expect investment in research to find alternatives, if at all possible. If there is no alternative, the current system, capitalism, would require that only the rich who can afford the price for the use of the resources would get access. However, there is a political dimension to consider; access may be altered by statute defining different access conditions other than wealth (granted, this is in general not our current system). I believe that MMT proponents recognise this. The future is determined by political choice, MMT could indicate the economic consequences. Your query, though valid, is more in the sphere of politics and choices rather than economics.

Bill has repeatedly stated that a “Sovereign Currency Issuer Can Always Purchase Whatever Is

Available For Sale In It’s Currency Of Issuance”.

I take this to mean that Sovereign Currency Issuers can be constrained, when goods and services they

want to purchase, are not available for purchase in the Currency they Issue.

In the case of New Zealand and Australia, both sovereign currency issuers, it is possible they could issue

purchase orders for petroleum, to be paid in their New Zealand Dollar or Australian Dollar, only to find

no product available. In this case, an alternative would be for these sovereigns to purchase GeoThermal Power, Wind Power, or Hydro Power instead.

In the case of domestic labor, a similar paradigm exists. As sovereigns, issuing their own currency, they

can buy services offered by domestic labor, until all available services are utilized, but no further. This of course, means that currency sovereigns must know the amount of surplus labor available, and must limit their purchases to the amount available. The JG works as Bill advocates because it offers to buy labor at what effectively is the Minimum Wage, but does not force labor to work for it at this wage. Hence the JG is self regulating, that is only the amount of labor currently in surplus, is available for JG employment, and is offered for such, because the remaining workforce is employed at higher wages, and unwilling to work at JG remuneration rates.

INDY