I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Australian primary education dumbed down by dumb politicians

Last week the former RBA governor, Bernie Fraser said that Australia was suffering from the “stupidity of government” by pursuing a budget surplus in present circumstances. He described our fiscal policy approach as being “just plain dumb”. It seems that the politicians are reflecting the standards that are now apparent in our educational system. The nation was shocked today with the news that we are not as smart as we like to make out. This Sydney Morning Herald story (December 12, 2012) – Australia’s disaster in education – is representative of many articles and discussions across today’s media offerings. The reports said that our children achieved “disastrous results in the latest international reading, maths and science tests”. The shock that the nation is experiencing is large today, about as large as the collective indifference to the damage that two decades or more of poor fiscal policy practice has been. We have allowed our governments to run down public infrastructure in pursuit of budget surpluses. We have let them deliberately reduce the capacity of our schooling system so that we can no longer keep pace with international standards. We have believed that this strategy exemplified responsible fiscal policy. It just shows how dumb our society has become. It also reveals, once again, the failure of the neo-liberal policy regime that dominates.

The full report of the international assessment – Highlights from TIMSS & PIRLS 2011 from Australia’s perspective – is worth reading as it outlines in detail what is being tested and how the comparisons are made. The process is not perfect as I note at the end of this blog.

Students are subjected to two types of assessment: (a) the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), and (b) the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)

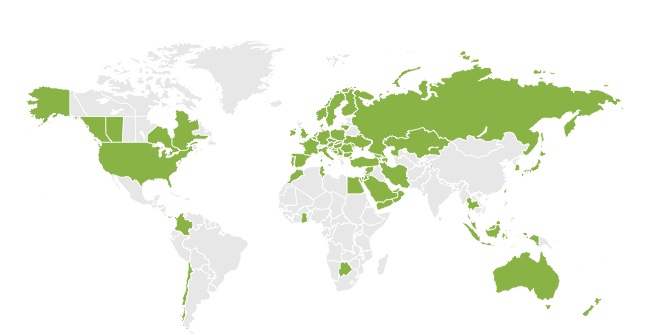

48 nations participated in the reading literacy (PIRLS) exercise and 52 in the Year 4 Science and Maths (TIMSS) exercise and 45 in the Year 8 Science and Maths tests (TIMSS).

The following map shows the geographical sample.

In summary, Australian primary school children in Year 4, we ranked 27th in the International Reading Literacy Study, although from rank 22 to rank 28 the results are not statistically different. Nations above us include Hong Kong (ranked 1), Russia (2), Finland (3), Singapore (4), Northern Ireland (5), US (6), Denmark (7), Croatia (8), Chinese Taipei (9), Ireland (10), England (11), Canada (12), Netherlands (13), Czech Republic (14), Sweden (15), Italy (16), Germany (17), Israel (18), Portugal (19), Hungary (20), Slovak Republic (21), Bulgaria (22), New Zealand (23), Slovenia (24), Austria (25), and Lithuania (26).

More troubling was the finding that around 24 per cent of Australian primary school students failed to meet even the minimum acceptable standards of proficiency in reading (literacy).

In terms of the mathematics and science test, “Australian students in ranked 18th for maths and 25th for science among year 4 students, and 12th for maths and 12th for science in year 8 out of 50 countries” (Source).

The ACER Report says that 57 per cent of Australian Year 4 students were judged to be:

‘somewhat affected’ by resource shortages related to reading, 54 per cent by resource shortages related to mathematics and 68 per cent by resource shortages related to science. Forty-six per cent of the principals of Australian Year 8 students reported similar levels of shortages in mathematics and 52 per cent in science.

Students attending schools in which principals reported that there were no resource shortages scored significantly higher than students from schools where principals reported being “somewhat affected” by shortages in Year 4 reading and mathematics and Year 8 mathematics. This trend was not found for science achievement.

So, overall, a fairly dreary lot.

The responsible Federal minister (Peter Garrett – former lead singer in the Midnight Oil) called the results “a wake up call” as if they should surprise us – something we are just discovering!

Those who work in the education sector at all levels have observed the drop in standards as the funding model has shifted public funding to private elite schools and squeezed our tertiary sector.

In an interview this morning with the ABC – Aussie schools flatline in global education tests – the Minister said the result were “further evidence that national changes to the school system are urgently needed”.

Memories are short.

In February 2012, just 10 months ago, the Government released the 300-odd page Review of Funding for Schooling was the first serious study of Australian educational funding since 1973.

The so-called Gonski Review (named after the panel chairperson who conducted the Review) reflected on the 39 year period over which a series of ad hoc changes have been made – mostly at the expense of the public schooling system.

Successive governments have ploughed increasing quantities of public funding into the private school system and then towards to elite end of that cohort. The evidence is that the private school system caters for the rich and high-income families, whereas the vast majority of students are “educated” in the public school system.

Australia has a deeply flawed school-funding model.

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) publish the – National Report on Schooling in Australia 2010 – (the latest is 2010), which provides a summary of the national education policy in Australia. It says:

Within Australia’s federal system, constitutional responsibility for school education rests predominantly with the six State and two Territory governments.

All States and Territories provide for 13 years of formal school education. Primary education, including a preparatory year, lasts for either seven or eight years and is followed by secondary education of six or five years respectively. Typically, schooling commences at age five, is compulsory from age six until age 17 (with provision for alternative study or work arrangements in the senior secondary years) and is completed at age 17 or 18.

The majority of schools, 71 per cent, are government schools, established and administered by State and Territory governments through their education departments or authorities. The remaining 29 per cent are non-government schools, made up of 18 per cent Catholic schools and 11 per cent independent schools. Non-government schools are established and operated under conditions determined by State and Territory governments through their registration authorities.

For those who are interested in the crazy system of educational funding in Australia this 2007 Report – Australia’s School Funding System – provides a good introduction (although policy changes since have occurred). The current situation remains similar to that outlined in this paper though.

An important point the paper makes is that:

… the process of school funding, including the way in which amounts are calculated, distributed and repor ted upon, is unavailable not only to the wider public but to some extent even to those working in education

You really have to dig in a number of places to piece together a story.

The Canberra Times article (February 21, 2012) – Gillard’s dissembling response undoes much of Gonski’s backbreaking work – described the funding model as:

… a tangled web of financial intrigue involving ancient deals negotiated between the Commonwealth, states and territories and underpinned by a dizzying array of financial incentives, anomalies, bribes, threats and add-ons that attach themselves during the political cycle.

In fact, governments at the federal and state levels deliberately obscure how much is being spent and where because then they can shift the blame back and forward among themselves when political needs suit.

The reality is that the Australian Constitution created a very poor matching of taxation powers and spending responsibilities, the former being dominated by the Federal Government and the latter mostly the domain of the States.

As a consequences the Commonwealth funds most of the educational budget but as a result of the redistribution of the taxation revenue to the States as general grants, most of the discretionary spending on education is performed by the State and Territory governments.

The essential findings of the Gonski Review were clear:

- “Over the last decade the performance of Australian students has declined at all levels of achievement, notably at the top end. In 2000, only one country outperformed Australia in reading and scientific literacy and only two outperformed Australia in mathematical literacy. By 2009, six countries outperformed Australia in reading and scientific literacy and 12 outperformed Australia in mathematical literacy.”

- “Australia has a significant gap between its highest and lowest performing students. This performance gap is far greater in Australia than in many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, particularly those with high-performing schooling systems. A concerning proportion of Australia’s lowest performing students are not meeting minimum standards of achievement. There is also an unacceptable link between low levels of achievement and educational disadvantage, particularly among students from low socioeconomic and Indigenous backgrounds.”

- “Funding for schooling must not be seen simply as a financial matter. Rather, it is about investing to strengthen and secure Australia’s future. Investment and high expectations must go hand in hand. Every school must be appropriately resourced to support every child and every teacher must expect the most from every child.”

- There should be a minimum public spend per enrolled student – the so-called “schooling resource standard” which would then be increased for children from disadvantaged or indigenous backgrounds. Students with a disability should also be given a loading on the mimnimum. Note that Gonski failed to address the issue of whether public funds should fund private schools per se. The ideological bias of public funding towards privileged private schools is a significant part of the problem.

- A $5 billion investment boost is needed to begin redressing these problems (in 2009 dollars).

The Gonski Review also clearly demonstrated that the schooling funding model has been infested with the growing dominance of neo-liberalism over the last three decades which has seen the funding skewed to the richer schools catering for the children of privilege. Further, the poorer schools where the disadvantaged families have to attend have fallen well behind.

There is now a small group of very wealthy, private schools that receive government assistance, while the vast majority of government schools, which cater for the majority of students and all of the children from disadvantaged backgrounds, are squeezed for public funds.

The private school lobby always claims that the private system caters for the disadvantaged and poor through special access arrangements – scholarships, etc. But the Gonski Review dispels that myth.

A small minority of children from families in the lowest quintile of the socio-economic advantage index make it to private schools.

It is clear from the data that the private schools take their students from high income, well-educated families. Our educational system is one that intrisically uses privilege to reinforce privilege.

The vast majority of Australian children (over 75 per cent) are educated within the public school system yet it has been starved for funds by successive governments seeking to not only cut back on government deficits but also to pander to the neo-liberal sentiments.

An overwhelming majority (around 80 per cent) of students from “relatively poor, ill-educated households” are educated within the public system. The same sort of proportions apply when we consider disabled students, indigenous (with the categories often overlapping).

But the Gonski Review shows that the public schools get less funding per student than the private schools, and this disparity widens dramatically when it comes to the elite private schools.

So the simple conclusion: the majority of our public schools are underfunded and the educational standards are going backwards. We are falling behind nations such as China and India, significant trading partners and it won’t be long before our standards of living fall as a result of the failure to invest in public education.

Today’s international assessments reveal that 25 percent of our Year 4 students have unacceptably low literacy skills.

Timed to coincide with the public release of the Gonski Report, was the – The Gillard Government’s Response to the Review Report.

Given they received the Report in December 2011 and took at least 2 months to come up with their response, one might have expected more than was produced.

First, the Government had stacked the Terms of Reference for the Review from the start by imposing the politically-motivated constraint that no school would lose any funding as a result of the outcomes of the Review.

So there could be no challenge to the outrageous system of funding that pumps millions of public dollars into the most elite schools in Australia and starves the public schools.

Second, the Gonski Review had identified “a need for an expanded stream of Australian Government capital funding” for Australian Schools.

The Government’s Initial Response rejected this:

In some areas, the Australian Government believes that the scope of proposed new funding contributions may be too large. For example, on capital spending, the Australian Government has recently completed the largest ever program of capital investment in Australian schools … we do not envisage the significant expansion of the Commonwealth’s capital funding role.

Third, the responsible minister – the very same Peter Garrett – who this morning was talking about “wake up calls” reacted to the release by telling a Press Conference that the Government’s priority was to achieve a budget surplus.

In the Government’s Initial Response we read:

The Australian Government is committed to returning the budget to surplus in 2012-13 and to ongoing fiscal responsibility. State and Territory Governments also face fiscal challenges, as do parents who do not wish to see school fees rise beyond their reach.

To take that next step requires that all of the stakeholders in education-states and territories, schools and school systems, teachers and parents- engage in constructive and productive dialogue.

In other words, the obsession with achieving the budget surplus will demand that the Government fail to address the serious issues in the Gonksi Review. All of us will suffer as a consequence.

Even the mainstream commentary is starting to see through their obsession. The Sydney Morning Herald article (February 22, 2012) – – said:

On top of this is the government’s budget surplus fetish which has no rational economic basis in the current situation but is designed simply to pander to Abbott’s political exploitation of public economic illiteracy.

It points out that the $A5 billion estimated by the Gonski Report necessary to improve Australian education “is about 1.3 per cent of the Australian government’s budget and could be readily funded from eliminating or modifying some tax anomalies”,

More to the point, it could be readily funded by the government simply spending the currency into use. At present the budget deficit is far too low given that 12.5 per cent (at least) of our overall available workforce is idle.

Over the last 2 to 3 decades we have been bombarded with a narrative from both State and Federal governments that budget surpluses were good, deficits were evil and public education outlays had to be funded from recurrent spending despite their obvious investment returns over many generations.

This fiscal austerity mentality gained traction because governments hacked into capital expenditure budgets more than they did recurrent budgets. That is a popular tactic because the government knows that the damage they cause by cutting back on capital infrastructure will not be quickly noticed by the voting public. It takes time for bridges, roads and an educational system, for example, to deteriorate.

A cut in pensions is felt immediately. A cut in educational expenditure takes a generation to work through. As noted above, those of us who work in the education system have been observing the deterioration in standards as our resources have been squeezed.

But the general public only really find out about the long-term damage that neo-liberalism has caused when these high-profile international assessment exercises are reported. As a sporting (competitive) nation, the realisation that we are so far down on the rankings is a major shock.

To find out that our educational system is falling well behind the world when all the Government talks about is being a global power is a shock.

Today, the public has seen the manifestation of the years of government obsessions with achieving budget surpluses and the resulting damage that has done to public infrastructure.

While the federal government, for example, preached how wonderful the surpluses it was running between 1996 and 2007, two things were happening.

First, the government surpluses were accompanied (and created) by the non-government sector (particularly the household sector) running increasing deficits. That sector is now carrying record levels of debt and are not in a spending mood any more – hence the slowdown in the economy.

Second, our public infrastructure was being run-down. The crucial area of education was being undermined and slowly but surely the results of that policy myopia have been revealing themselves.

This policy approach has been justified, in part, by the so-called “intergenerational challenge” (or the ageing society debate).

The claim is that failure to act now with respect to fiscal consolidation will result in unsustainable fiscal consequences and, even, according to the more extreme versions of the story – the government running out of money.

It is clear that governments should always be forward looking and accept that its fiscal position will reflect changing challenges in terms of providing adequate public services and infrastructure while always be seeking to ensure that aggregate demand is sufficient to maintain production at the levels required to fully employ the available workforce.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, national government finances can be neither strong nor weak but in fact merely reflect a “scorekeeping” role.

MMT tells us that when a government boasts that a $x billion surplus, it is tantamount to saying that non-government $A financial asset savings recorded a decline of $x billion over the same period.

So when a government aims to achieve a surplus it must also be wanting the non-government $A financial asset savings to decline by an equal amount.

For nations that run current account deficits over the same period, we can then interpret that aim as saying that it is fiscally responsible to drive the private domestic sector (as a whole) into further indebtedness. That is a consequence of such behaviour. It is not what MMT would suggest is responsible fiscal management.

It follows that the entire logic underpinning the “ageing society-fiscal consolidation” debate is flawed. Financial commentators often suggest that budget surpluses in some way are equivalent to accumulation funds that a private citizen might enjoy. This has overtones of the regular US debate in relation to their Social Security Trust Fund.

This idea that accumulated surpluses allegedly “stored away” will help government deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population lies at the heart of the neo-liberal misconception.

While it is moot that an ageing population will place disproportionate pressures on government expenditure in the future, it is clear that the concept of pressure is inapplicable because it assumes a financial constraint.

The standard government intertemporal budget constraint analysis that deficits lead to future tax burdens is ridiculous. The idea that unless policies are adjusted now (that is, governments start running surpluses), the current generation of taxpayers will impose a higher tax burden on the next generation is deeply flawed.

The government budget constraint is not a “bridge” that spans the generations in some restrictive manner. Each generation is free to select the tax burden it endures.

Taxing and spending transfers real resources from the private to the public domain. Each generation is free to select how much they want to transfer via political decisions mediated through political processes.

When modern monetary theorists argue that there is no financial constraint on federal government spending they are not, as if often erroneously claimed, saying that government should therefore not be concerned with the size of its deficit. We are not advocating unlimited deficits. Rather, the size of the deficit (surplus) will be market determined by the desired net saving of the non-government sector.

It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that the economy achieves full employment. Accordingly, if the goals of the economy are full employment with price level stability then the task is to make sure that government spending is exactly at the level that is neither inflationary or deflationary.

This insight puts the idea of sustainability of government finances into a different light. The emphasis on forward planning that has been at the heart of the ageing population debate is sound. We do need to meet the real challenges that will be posed by these demographic shifts.

But if governments continue to try to run budget surpluses to keep public debt low then that strategy will ensure that further deterioration in non-government savings will occur until aggregate demand decreases sufficiently to slow the economy down and raise the output gap.

In terms of the challenges presented by rising dependency ratio, the obsession with budget surpluses will actually undermine the future productivity and future provision of real goods and services.

The quality of the future workforce will be a major influence on whether our real standard of living (in material terms) can continue to grow in the face of rising dependency ratios.

Governments should be doing everything that is possible to educate, train and employ our youth so that they will achieve higher levels of productivity into the future and offset the inevitable rises in the dependency ratio.

This requires:

1. That there is significant investment in education – the Gonski Review demonstrates that the Australian system is failing.

2. There should be ways to ensure the youth are either in education or work.

Today’s results, on the back of the Gonski Review, show how our “dumb” governments are failing us.

By pursuing a budget surplus when there is clearly significant excess productive capacity in Australia and when the private domestic sector is highly indebted the government is not only damaging the present but also undermining the future.

Maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. It is madness to exclude our youth – many of whom will enter adult life having never worked and having never gained any productive skills or experience.

Those that exit our formal schooling system are also increasingly falling behind.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

But it is also clear that our schooling system is failing us – right back to primary level. So not only are the current youth who desire to enter the labour force being forced into idleness but the next cohort are becoming increasingly illiterate and struggle with maths and science.

Ultimately the ageing society challenge is about about political choices rather than government finances. If there are goods and services produced in the future, then the sovereign government will be able to purchase them and provide them to the areas of need in the non-government sector.

The challenge is to make sure these real goods and services will be available.

In terms of today’s revelations, the responses to the results demonstrate how entrenched the neo-liberal ideology has become. Neo-liberals like to blame individuals for what is a systemic failure. So they accuse the unemployed of being lazy despite there being 5 people looking for every available job.

They call refugees “queue jumpers” and the disabled “work shy” – and the rest of the pernicious, scapegoating nomenclature they use to individualise tribulation and avoid admitting that their policy approach is causing systemic failure.

Today, the commentators were out in force blaming the teachers – poor attitudes, low quality – etc. The teachers have to improve was the message coming out. School Boards have to have more capacity to hire and fire. Individualism – the neo-liberal response to all the problems that approach causes.

There may be bad teaching going on. But the reason for that is that secondary schools are producing lower quality entrants to the University system, which in turn is being starved for funds. High quality teaching staff come out of well-resourced and innovative university programs that take well-prepared students from a high class secondary education system.

All those links and requirements are suffering in Australia as a result of the overall economic policy environment.

Later today, there was a Xmas story in the Melbourne Age that resonated with this morning’s revelations. The story – ‘Merry Christmas. You’re fired’ – tells us of a trades teacher in the Vocational training system – TAFE.

We read that one teacher received the following letter:

Dear Ben, Due to the significant financial cuts made in the recent state budget…I regret to advise that we will not have the same number of positions available for 2013…your last day in the role Teacher Plumbing will be 14.12.12.

He is “one of hundreds of TAFE teachers statewide who will not have their contract renewed next year due to the state government’s $300 million budget cuts to TAFE”. That is happening in Victoria. The same is going on across the nation.

There is no shortage of student demand for these vocational courses. This trend is going on at the same time that private businesses are claiming there are major skill shortages in Australia which are preventing investment in high productivity new developments.

Myopia at its best.

Conclusion

The idea that it is necessary for a sovereign government to stockpile financial resources to ensure it can provide services required for an ageing population in the years to come has no application.

The best thing to do now is to maximise incomes in the economy by ensuring there is full employment and ensuring our public schooling system is well-resourced and producing first-class outcomes by rising World standards.

This requires a vastly different approach to fiscal and monetary policy than is currently being practised.

The irony is that the pursuit of budget austerity leads governments to target public education almost universally as one of the first expenditures that are reduced.

The results of almost 20 years of cutting back on public school funding (in terms of growth) has seen Australia spending well below the OECD average on education. The results of that austerity is that we are producing a dumb society and falling behind the rest of the world. We will not maintain our high standards of living for long at that rate.

Dumb politicians dumbing down our schools. Bad mix.

As a note of caution – the international educational comparisons were designed by the OECD and many criticise the contextual relevance of the tests. The ABC reported that a leading Norwegian educational expert warned that “students were being taught for a result rather than developing a passion” for learning.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

A while ago I happened to be discussing education funding in Australia with someone. That very report by Andrew Dowling seemed to be the best and most intelligible source. I’m glad to see it has your recommendation.

“… the process of school funding, including the way in which amounts are calculated, distributed and reported upon, is unavailable not only to the wider public but to some extent even to those working in education.”

was illustrated in that discussion, because the person who had violently disagreed with my statement, basically that “the Commonwealth funds most of the educational budget” was a usually very well-informed Australian educator!

Hi Professor.

This is entirely off topic, I know, but here is an interesting passage from RBA governor’s speech yesterday.

Any thoughts?

Bill, I would like a reply to this post please. I agree as far as you go. However, I would like to see you go further and move MMT into the following areas of analysis as mandated by real world factors.

1. The impact of peak resource extraction on economics. Peak oil appears to have occured in 2006. Many other peaks appear imminent. This implies the end of quantitative growth. This final limit is near while we keep growing exponentially. Essentially, all limits are near when exponential growth is involved. The end of quantitative growth does not necessarily imply the end of qualitative growth. However, it could imply that if the crunch at the limits-to-quantitative-growth juncture is severe and an ensuing recession/depression is severe too.

2. I would like to see more ideological and sociological analysis on why you think our ideological and conceptual malaise is so severe at the level of politics, discourse and public knowledge / attitudes. I surmise you are not a political scientist nor a sociolosgist (though you might have more Majors than I am aware of) but I am sure you have a number of pretty well-founded theories on this front. I find the sheer persistence of failed ideology and failed economics (neoconserative and neoclassical) particularly baffling and frustrating.

This insanity has been going on for about 40 years. Considering I am 58, I have had to put with this neocon, monetarist bulldust distorting society and indeed my own life for my entire adult life to date. I am not alone in this of course. In the end I resigned from work in total disgust and disengaged from the entire paid working world to live much more frugally but with much less angst.

I regard myself an an inherently well-intentioned, well-educated, intelligent, active, experienced and mature person. Isn’t there something wrong when people like that are driven to disengage from the public economic world? I know from a lot of anecdotal evidence that it aint just me.

(Footnote: I disagree with some of the secondary technical and rhetorical arguments of MMT but my quibbles are relatively minor.)

While everything Bill has said is true, it also should be emphasised that politics is largely organised lying, and that all governments tell lies to their own citizens. The statements and statistics put out by governments should be taken with a grain of salt. The extent to which people in main street are able and willing to do so is a measure of their political awareness, sophistication and general understanding of the forces which are moulding and controlling their lives.

It should be obvious that austerity budgeting will be manifested in the first instance by attacks on soft targets like education. However it suits the convenience of the powerful vested interests who control the mass media and fund our political parties to keep society at large in a state of ignorance and deception, and to mask the reality of a two tier education system which serves to maintain the status quo.

How right you are John Hermann but it is unfortunate that that is the truth of matters.

There may be problems with the education system generally.Maybe a few teachers are not up to to task.

But education starts in the home well before school entry.

How many parents read to their children from a very early age?

How many parents are truly literate?

How many homes have books in the house on a regular basis?

How many parents often use public libraries and encourage their children to do the same?

How many parents vegetate in front of the TV and encourage their children to do the same?

How many parents use TV as a child minder?

Let’s get one thing straight,TV is a literacy killer.

Education is primarily a social issue not an economic one unless a recalcitrant government (Liberal or Labour) refuses to commit the necessary resources.