At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

When you’ve got friends like this – Part 9

The progressive side of politics is at the best of times, fragmented. The conservatives are much more organised and fund various “think tanks” very generously. These think tanks then provide the arguments upon which the conservative attack on government intervention is justified. Various multilateral agencies – such as the IMF and the OECD – are co-opted into this conservative putsch. But occasionally there is some major piece of work that is hailed as the progressive manifesto. A 2011 offering – Crisis, Slump, Superstition and Recovery: Thinking and acting beyond vulgar Keynesianism – is now being held out as a model for British Labour to follow. However on closer examination it becomes obvious that this offering is another one of cases when friendly fire shoots the progressive movement in the foot. You can read the previous editions of this theme – When you’ve got friends like this – to see what the problem is. The simple point is that a truly progressive social agenda has to be grounded in solid macroeconomic principles. Trying to carve out a progressive agenda within a mainstream macroeconomic framework undermines the credibility of the former and plays straight into the hands of the conservatives.

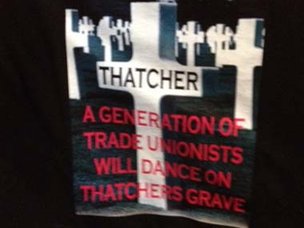

The UK Trades Union Congress held their national Conference in September and had some “merch” on sale which upset the conservatives in Britain. The BBC ran a story at the time (September 11, 2012) – Anger at Thatcher death T-shirts on sale at TUC. The T-shirt in question, spelling errors and all, is shown in the following picture.

The Tories were duly inflamed and took time out from supporting fiscal austerity that is condemning millions of British people to rising poverty, to sound off about the improper nature of the garments. It is a pity they don’t generalise their anger and oppose their own party’s attacks on the disadvantaged.

The ageing Baroness certainly caused the working class elevated grief but if you reflect on what the progressives have been able to construct as a political defense since that time you realise how the current Tory government aided and abetted by the traitorous Lib Democrats, have been able to get elected to push the current, pernicious policy agenda.

I guess celebrating someone’s death is not exactly my style of political commentary but that particular aspect of the reaction is, in my view, of secondary importance.

But from my perspective, the T-shirt signalled that the progressive movement is still labouring over losses in the past and still draws on conceptual frameworks which are flawed in their construction.

The reality is that there has been very little progress towards a well-constructed conceptual critique of the erroneous neo-liberal cum Monetarist view of the economy. It still reigns supreme, even in the minds of those who it impoverishes.

In this light, there was a UK Guardian article (October 28, 2012) – Neither Keynes nor the market will save Labour – which discussed, in an uncritical way, a piece of work that came out a year ago (September 28, 2011).

The lapse of time is explained by the fact that the earlier article – Crisis, Slump, Superstition and Recovery: Thinking and acting beyond vulgar Keynesianism – written by Tamara Lothian and Roberto Mangabeira Unger and published in Global Policy, was recycled as an Op Ed/Blog recently (October 23, 2012).

The blog – Stimulus, slump, superstition and recovery: Thinking and acting beyond vulgar Keynesianism – is the text that the UK Guardian refers its readers to and is, in fact, a short-version of the original paper.

The Guardian’s message to its readers is that the British Labour Opposition:

… hasn’t yet got a clear enough, simple enough, big-picture economic alternative. It’s still vulnerable to the Tory charge of being the party of splurge ….

… the truth is that repositioning Labour on the role of the state, and producing tough proposals on welfare, don’t quite reach the heart of the dilemma, which is how to remake our economy. At present, it’s unbalanced, unfair, undemocratic and anaemic. Whether the economy grows in one quarter is hardly the point; the general economic failure is profound. That’s where Labour needs to concentrate.

The Guardian journalist then refers readers to the “deepest thinking on this I’ve come across” and links to the recent IPPR article noted above. The journalist makes no mention of the earlier more detailed paper so I am unsure if she has read it or not.

But the precis version captures the main points anyway – sufficient for anyone who was on top of macroeconomics to realise that this “deep thinking” is, in fact, very shallow when it comes to providing an alternative critique of the current economic orthodoxy.

In my view the “deep thinking” provides no basis for mounting a progressive attack. Some of its ideas – such as “democratising” workplaces have appeal.

But the overall argument including the alternatives the authors perceive as being viable is grounded in what is essentially a deeply flawed mainstream representation of macroeconomics.

Once you straitjacket alternatives in mainstream macroeconomics and accept all the fallacies that come with that approach, then the game is largely lost and the capacity to gain political traction is limited.

The race to the so-called “centre” among major parties in the advanced nations is a reflection of this straitjacketing. In my view, the progressive side of politics has to outrightly shed the neo-liberal macroeconomic framework and then educate the population about the true alternatives that are available to a currency-issuing state.

That might take more than one political cycle for success. And therein lies the problem. The parties are hungry for power and will eschew true leadership to get it. I have spoken to many so-called “progressive” politicians, even though who claim to be on the “left”, and the standard response I get is that the public are not ready for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) even if it is a viable alternative. For them, it is better to “play it safe” and concentrate on “social policy” or other policy differences between themselves and the conservatives.

The problem is that they then become obsessed with destructive macroeconomic policy stances that prevent the achievement of the “progressive parts of their platform. This is a problem I have had with The Greens, who have an excellent social and environmental platform, but have hamstrung themselves in neo-liberal macroeconomics.

Think about the current Australian Labor government, which is pursuing a budget surplus “at all costs” because they think such a strategy portrays them as good economic managers. This is at a time when at least 1.5 million workers are either unemployed or underemployed (that is, more than 13 per cent of the available labour force).

They will probably fail to achieve their much-vaunted surplus because the economy is slowing and their tax revenue is falling well short of their forward estimates. That will also be a political disaster for them because the Opposition will appeal to the ignorance of the voters and represent what will actually be a good thing for the economy (the failure to achieve a surplus) as a failure.

But in trying the Government will be inflicting unnecessary grief on the economy. So in the end – it is a lose-lose – for the progressive side of politics.

The Stimulus, slump, superstition and recovery: Thinking and acting beyond vulgar Keynesianism – article (and the longer version), demonstrates why the progressive side of politics is doomed to fail.

The authors start in this way (quotes are from the longer original article):

Nothing astonishes more in the present debate about recovery from the slump that followed, in the richer economies, the crisis of 2007-2009 than the poverty of the ideas informing the discussion. It is as we were condemned to relive a yet more primitive version of the debates of the 1930’s.

Which is a precursor for them to introduce their main thesis:

On one side, we hear the argument for fiscal and monetary stimulus: the more the better. The intellectual inspiration of this argument is almost exclusively vulgar Keynesianism; with each passing round in the debate, it becomes more vulgar.

Vulgar Keynesianism? What exactly is that?

Vulgar Keynesians apparently believe that major slumps in aggregate demand can be addressed with fiscal and monetary stimulus. The alternative of “market fundamentalism”, has according to the authors, made a comeback because of the “nostrums of the vulgar Keynesians” and so “fiscal austerity, monetary common sense, and a return to fundamentals — that is to say, the established institutions of the market economy, with a minimum of governmental action” are dominant because of the vulgarity of the Keynesian approach, which is doomed to fail.

I would not actually say that the “market fundamentalism” is in “resurgence” – its dominance was barely challenged, even at the height of the crisis. Policy structures, based on the proposition that a self-regulating market would deliver sustained prosperity for all, led to behaviour that created the crisis.

The same ideology has prevented fiscal policy from dealing fully with the resulting collapse in aggregate demand and promoted the relatively ineffective monetary policy to the centre stage. The combination of short-lived macroeconomic interventions certainly demonstrated that fiscal policy is highly effective in adding to aggregate demand and that monetary policy is an inappropriate vehicle for large-scale spending stimulus.

But the interventions hardly led to a demise of the free market orthodoxy.

The authors claim that given the current “conditions of a contemporary democracies and markets, no fiscal and monetary stimulus is ever likely to be large enough to help ensure a broad-based and vigorous recovery from a major slump”.

This is because the policies will “arouse opposition both because of the present interests that it threatens and because of the future evils that it risks producing”.

Which means firstly, that the argument is that political views cannot be influenced via leadership. Political persuasion used to be about articulating an alternative and then developing the narrative that advanced that way of thinking. It was about developing manifestos and visions. But these authors think that just because there is an opposition to a policy in the current context that governments have insufficient latitude to move.

But then think about the last five years. The IMF among others were advancing fiscal consolidation and austerity as the primary government responses to the crisis, playing on this dislike among economists etc for fiscal intervention of a progressive kind. All sorts of so-called research papers were produced to justify the austerity stance.

Journalists all around the world were then co-opted to act as the mouthpieces for these organisations and popularised the austerity myth. The outcomes of these policy stances have been disastrous.

Then, without even blinking an eye, the IMF announces recently that their “modelling” (if you can call it that) was seriously wrong and that spending multipliers are likely to be up to 1.7 rather than 0.5. That means that the entire case for austerity fails by their own word.

The authority that was used by politicians and the hectoring financial media, not to mention the so-called right-wing “think tanks” to advance austerity collapses in that one revelation. A dollar of fiscal injection doesn’t lose 50 cents but gains 70 extra cents in private spending. That is a mammoth difference.

Of-course, that revelation was no surprise to those who support what these authors claim to be “Vulgar Keynesianism”. Why haven’t the progressives been shouting these points from the roof-tops, instead of feeding journalists with nonsense about the “evils” of fiscal policy?

And exactly what are these alleged “future evils” that our “progressive commentators” claim may arise if monetary and fiscal stimulus is adopted as a response to a non-government spending collapse?

At this point, all the usual neo-liberal, macroeconomic textbook myths are rehearsed – one after another.

We read that:

In the practice of monetary policy, it is easy to jump from deflation to inflation, and then to see inflation combined, as it has been in the past, with, stagnation.

Maybe the authors will help us understand the recent two decades in Japan where what they would term very liberal monetary policy – the type advocated by the “vulgar ones” – has held interest rates close to zero and significantly expanded the central bank balance sheet – yet inflation has been near zero.

Where exactly in the past has monetary policy jumped from “deflation to inflation” and then stagflation?

They do note that at present the commercial banks have an ” abundance of liquidity” while “households and firms” are determined “to free themselves from the burden of debt accumulated in the years leading up to the crisis”. This apparently is a quandary and paradoxical.

Why so? It is perfectly explainable if there is an understanding of how monetary systems operate and how human psychology functions in times of economic stress.

The authors lack the first capacity unfortunately.

They correctly note that the pre-crisis period was dominated by the rise of “inequality-generating forces” and that a “vast portion of profits were concentrated in financial firms”, as a result of various policy changes that engineered the redistribution of national income away from wages towards profits.

That is a theme I have been writing about for at least a decade now – long before the crisis manifested. It was clear that the growing disparity between real wages growth and labour productivity growth, which allowed the profit share to rise significantly, would either create a recession (through loss of purchasing power growth in relation to output growth) or require increasing access to credit to sustain consumption.

We first saw the latter and then the former as the credit cycle collapsed under the weight of precarious private balance sheets.

And it is true that there are “vast stores of idle capital … in economies populated by households and firms over their heads in debt”. That is the legacy of the credit binge and a return to more normal consumption and investment spending behaviour in the aftermath of the collapse. It is not a quandary or a paradox.

It requires the government sector to also return to more normal behaviour, which means using fiscal deficits to fill the non-government spending gap and ensure that the saving desires of households can be realised via income growth. That is straightforward (Vulgar) Keynesian Economics 101.

But this is what the authors tell their readers:

In such a circumstance, the expansion of the money supply by central banks (called by a barrage of obfuscating names such as “quantitative easing”) may help avoid serious and destructive deflation without, however, ensuring a vigorous recovery. It cannot, however, help ensure a vigorous recovery in economies full of families and companies anxious to escape an overhang of debt.

QE and related balance sheet operations do not expand the money supply. They just add to bank reserves and amount to asset-swaps. The use of these balance sheet operations in the current crisis has nothing to do with Keynesian thought – vulgar or otherwise.

The reliance on monetary policy is a residual from the mainstream rejection of fiscal policy. That rejection has been demonstrated to have no evidential basis. Fiscal policy when used is very effective (think about those new IMF spending multipliers).

So what do they say about fiscal stimulus?

We read:

Fiscal stimulus faces similar limitations and difficulties. When it takes the form of cutting taxes, the money saved by households (and in effect spent by the government) is likely to go disproportionately into the paying down of corporate or household debt rather than into increased consumption. To the extent that the beneficiaries of tax cuts are cash-rich individuals and companies, the windfall may simply stoke the already vast store of capital with nowhere to go.

There are two aspects to a “balance sheet recession” – of the type that the world is enduring at present – which are different from typical recessions.

First, the balance sheet part has to be resolved by the non-government sector reducing its debt levels. That process is painful and takes a long time. In the meantime, private spending is subdued and incapable of supporting growth although the deleveraging process requires income growth to be successful. This is because private saving is a function of income growth. You cannot easily have the former without the latter.

Which motivates the second aspect. Governments have to be prepared to step in for extended periods and run deficits sufficient to drive income growth which supports the non-government sector’s balance sheet restructuring process.

So it is crucial that some of the “income growth” goes into increased rates of private saving. That just means that the size of the fiscal intervention has to be that much larger to incorporate the rising leakages from the aggregate spending stream arising from the increased private saving rates and the reduced spending rates.

The authors then say that spending initiatives that “put money directly in the hands of those who are more likely to spend it” (for example, the unemployed) and/or an “ambitious program of public works” have two drawbacks:

The first qualification is that the value of such forms of stimulus depends on what comes next. Will the extra money spent by the jobless cause more investment and employment? Will the infra-structure projects help entice more risk-taking and innovation, creating a physical basis for the diffusion of more advanced technologies and practices throughout broader sectors of the economy? …

The second qualification is that whereas the ultimate effect of such actions on economic growth is both speculative and remote, the burden that they impose on governmental finance is immediate … the short-term effect on increased demand may soon wane, while the worsened fiscal position of the government inhibits it from undertaking the next round of growth and innovation-friendly measures.

Which tells you that they do not understand monetary economics.

First, the logic of a government fiscal intervention is to provide sufficient spending stimulus to motivate economic growth and support the balance sheet restructuring process. The latter has to be resolved before the private spending will start supporting demand and income growth itself with lower levels of budget deficit spending.

While it is better that government spending actually contribute to the long-term prosperity of the nation – via improvements to education, health and infrastructure – the basic aim is to keep employment growth strong and give the non-government sector sufficient time to get their balance sheets into a sustainable shape.

Second, the ultimate effect on growth is not speculative at all. These arguments questioning the efficacy of government spending are the same that are used by the neo-liberals. The IMF was used to give them credence because then the neo-liberals could disguise their ideological distaste for government spending (at least all spending that did not result in handouts for the elites – corporate welfare and the like) in technical talk about low fiscal multipliers.

That scam is over and the ideology is there for all to see.

A dollar of government spending stimulates GDP by one dollar in the first instance. The multipliers (say of 1.7 or more) then mean that private consumption is stimulated some more and so it goes.

We know that budget deficits do not drive up interest rates – the so-called financial crowding out myth.

We know that some of the stimulus spending leads to rising imports but that is taken in to account when we estimate the multipliers to be well in excess of one.

The only debate is where to put that stimulus – and that is a legitimate argument. I would put it in the hands of the poor and the disadvantaged and ensure that the government created a maximum number of jobs per $ spent.

But the claim that we are unsure that the spending is stimulatory has no evidential basis.

Third, there is no applicability to the term “burden”, when considering the budget of a currency-issuing government. That is just the loaded terminology that the neo-liberals use to attack net public spending.

What concept of burden could there be for a government that issues its own currency? There is clearly a resource burden whenever the government spends. All spending programs aim to garner real resources in one way or another.

So that is the economic burden of government spending – the real resources that are deployed in the program. When the economy is in recession or slow growth and unemployment is high, the opportunity cost of that resource deployment is low.

When an economy is at full capacity then increased government spending has to slug it out with non-government spending aiming to deploy the same resources. Then the opportunity costs rise but we cannot conclude anything about that until we examine what each sector wants to do with the real resources it is fighting over (via spending).

In many cases, it will be better for society to have the government take control of those resources and then squeeze the non-government sector’s demand for them by increasing taxes etc.

But that is not what these so-called progressive authors are talking about.

There is no applicable concept of a “worsening fiscal position”. That is also loaded neo-liberal terminology. The fiscal balance is neither good nor bad. What we would consider to be good or bad is the state of the real economy.

So high unemployment and stagnant real GDP growth is bad (subject to qualifications concerning environmental sustainability) and full employment and supporting economic growth is good.

Government net spending positions (that is, deficits) have to be whatever is required to ensure there are good outcomes and an avoidance of bad outcomes. Those positions will be determined by the spending choices of the non-government sector.

Please read the following introductory suite of blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – to learn how Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) constructs the concept of fiscal sustainability.

Finally, the authors rattle the “bond markets will note tolerate deficits” can:

The worsening of the fiscal position of the state may in turn arouse the specter of a crisis of confidence in the sovereign debt: in the ability of the government to repay its obligations over the long term. The United States will continue to be the country least vulnerable to this form of pressure so long as it detains the world’s reserve currency, and can pay all of its obligations in a currency that it is free to print as well as to count on the willingness of cash-rich countries and governments to help finance its profligacy. However, the risk of default is not the sole or normally the most significant form of declining confidence. The outward movement of capital, although less dramatic, can be nearly as decisive.

Textbook neo-liberalana. But still very wrong.

First, note the loaded terminology – “finance its profligacy”. The impression that the authors convey is that budget deficits are wasteful extravagances. What is profligate about a budget deficit? Nothing as it stands.

Perhaps a dictator that runs deficits to build statues of him/herself in city squares (next to the icons of colonial religions!) is wasteful and largely unproductive.

But is a large-scale public works program that employs millions and pushed the workers, who would otherwise be unemployed, above the poverty lines profligate?

Second, the risk-free nature of US debt has nothing to do with its so-called “reserve currency” status. That is another major myth. All currency-issuing nations provide risk-free debt should they choose to issue public debt to the private bond markets. Even the smallest nation in the back-blocks of anywhere can always honour its liabilities in its own currency. Political turmoil may lead to defaults etc but that has nothing to do with the financial capacity of such a currency-issuing government.

Third, “cash-rich” countries do not “finance” the spending of currency-issuing governments. Another myth. China is not funding the US government.

A foreign government might hold a US government bond. What does that mean? It means simply, that the US government is liable to pay them interest (in dollars) and upon maturity of the bond, the government will pay the holder the face value of the bond – in dollars.

How did the foreign entity get the dollars to buy the bond? They initially get dollars (in this case) by exporting goods and services – consumer goods, investment goods etc – to the bond-issuing nation. Real resources go to the bond-issuing nation. That sounds like a good deal – the nation gets an increased quantity of real goods and services in return for providing the exporting nation with bits of paper, which initially earn no interest.

They then buy the bonds with the cash from the export sales that was sitting in (this case) in US banks. The bond is attractive because it returns interest whereas the cash deposits return nothing.

The foreign holder can always sell the bond. They just get a bank account in dollars (a deposit) in return for surrendering the bond and its related interest income flow.

If that is not desirable then they have a problem. They have to produce more at hometo generate the same employment and income growth that the exports provided for. In that case, the increased domestic income would spur import demand, which would lead to other nations exporting to them.

Fourth, what exactly is capital flight? I will write another blog about this another day. But if the foreign investment has been in productive capital then it is hard to see this “leaving” the nation. Speculative flows are largely unproductive so the real capacity of the nation is not affected when they change.

But then, reflecting on the opening – Margaret Thatcher did manage to sell millions of dollars worth of productive capacity in the textiles industry to the Italians in the early 1980s, who then promptly exported the clothing etc back to Britain.

Conclusion

The Guardian presented this piece of work as a progressive solution for British Labour. The journalist said:

It is in this vision of a diverse, democratic economy that Labour will find its best answer to passing economic statistics and the route back not just to power, but to being useful in power.

The British Labour Party would be mad to embrace the logic of this attack on “Vulgar Keynesianism”. It is not a progressive piece of analysis at all despite holding itself out as such.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Top blog Bill. One of the best.

“But if the foreign investment has been in productive capital then it is hard to see this “leaving” the nation.”

The one valid point there is that if they own the real production system, they can close it down and then sit on the site and refuse to let anybody else use it.

Dear Bill

As I see it, capital flight can be a problem because it affects the exchange rate. Suppose that foreigners hold a lot of Brazilian bonds and stock because Brazil is hot. Then Brazil goes out of fashion among foreign investors. They all sell their real-denominated assets and with the proceeds they buy dollar-denominated assets. Surely, that must make the exchange rate of the real fall drastically. That’s the problem with cross-border portfolio investing. It can create havoc with the exchange rate, which really should be determined by trade flows, not by flows of speculative capital. The more capital flows determine the exchange rate, the more international trade will be destabilized by wild exchange rate fluctuations.

Regards. James

Why should it take a long time? If one correctly perceives the banking system as a government backed/enforced counterfeiting cartel that has cheated both debtors and non-debtors then the solution is obvious – a ban on further counterfeiting (so-called “credit creation”) and universal restitution for the entire population financed by the monetary sovereign with pure money creation. Moreover, a ban on further credit creation would be massively deflationary by itself (as existing credit was repaid with no new credit to replace it) so the restitution could be massive too and if metered appropriately could be done without significant price inflation or deflation risk.

Steve Keen (a neo-Keynesian) advocates something similar in his “A Modern Debt Jubilee.”

Those productivity increases were likely financed with the workers’ own stolen purchasing power via loans from the counterfeiting cartel, the banks.

So the population was driven into debt, debt that the equity illusion caused by the bank-induced housing boom allowed them to qualify for.

If not now, then when?

@ James Schipper: Then as the real drops in value, Brazilian assets become cheaper for foreigners and then they buy them back and the real increases a bit and on and on it goes. The capital sloshes around looking for the best return, all the while the factories and workers in Brazil hum merrily along. Cheers.

Neil W

Tax them. Any site left empty is taxed, the longer you keep it empty (non productive) the more tax you pay. Negociate with the owners to let the equipment be sold to a domestic firm at a discount, or perhaps nationalise them (like the Argentinians have just done). Lots of ways of skinning the cat.

“Lots of ways of skinning the cat.”

As long as your party funding doesn’t depend upon the owners…

“A dollar of government spending stimulates GDP by one dollar in the first instance. ”

No, a dollar of government spending on imported goods stimulates GDP by exactly nothing.

“Second, the risk-free nature of US debt has nothing to do with its so-called “reserve currency” status. ”

No it has everything to do with it. While you are totally correct that any nation can issue risk-free debt in its own currency, you clearly haven’t lived in a third world country where people consider their wealth in USD and hence holding a supposedly risk free bond in local currency is not risk free on your wealth, especially when especially a government’s action drives inflation up and the currency down. There is a big difference between theory and reality. The US enjoys a specially position given it is firstly the global trade currency, removing the need for the US to acquire forex in order to import, and secondly, the US is the largest provider of investment to the rest of the world, with over $21trn invested globally, meaning that at times of global shocks, US investor begin pulling assets back to the US supporting the currency.

“Fourth, what exactly is capital flight? I will write another blog about this another day. But if the foreign investment has been in productive capital then it is hard to see this “leaving” the nation. Speculative flows are largely unproductive so the real capacity of the nation is not affected when they change.”

However, if speculative flows causes shares prices to crash or interest rates to rise, they impact the ability of productive enterprises to raise funding cheaply and may impact future productive capacity

if chronic under demand in the OECD countries

is caused by the declining ratio of incomes to GDP

and rising inequality of those incomes

how will fiscal stimulus and job guarantees at low incomes rectify this decline?

higher and broader( including the low payed )welfare payments divorced from bond issue at say 30% of GDP annually

could provide required levels of stimulus for strong growth and employment

but if they taper for the majority of workers could address the wage productivity gap

with an income backstop created by the currency issuer some wages may need to rise to attract workers

the level and breadth of the welfare/income stimulus could respond to economic contingencies

for employers to increase wages

Hi Bill,

“The reality is that there has been very little progress towards a well-constructed conceptual critique of the erroneous neo-liberal cum Monetarist view of the economy.”

Have a read of The Courageous State, by Richard Murphy and check out his blog at http://www.taxresearch.org.uk

I believe it goes some way towards providing that critique plus offering a way out of the mire.

Cheers

Dear Dr. Mitchell

“I have spoken to many so-called “progressive” politicians, even though who claim to be on the “left”, and the standard response I get is that the public are not ready for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) even if it is a viable alternative.”

I don’t suppose it would be possible to hear more about this sort of thing in a future blog?

Ben Johannson

go to

Neo-liberals on bikes …

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=20176

on Bill’s blog to see the quote below.

Also, Stephanie Kelton mentions an example in the presentatin she and Warren Mosler made at:

Modern Money and Public Purpose 2: Governments Are Not Households

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2012/10/modern-money-and-public-purpose-2-governments-are-not-households.html

Quote from Bill’s Blog:

best wishes

Graham Wrightson

Paul F.

Even third world governments can afford to purchase anything which is for sale IN THEIR OWN CURRENCY. They do not need to sell government bonds to anyone to do so. If they spend to excess, it will be inflationary and will undermine the currency. In the short run, during a switch to MMT-inspired macroeconomic policy, exchange controls might be used to limit outward specultive flows while the new approach is being understood by market participants. But the fact remains that any sovereign government with its own currency and a floating exchange rate regime is in this position. There is no reason to raise interest rates unless you are aiming to fix the exchange rate, which we do not (in general) advocate – although Keynes/Paul Davidson-style Post-Keynesian arguments can be legitimately made for a form of fixed exchange rate regime which does not have a deflationary bias. If there is currency depreciation, it of course implies potentially falling real incomes in the domestic economy, but that does not change the fact that a monetary sovereign government will be able to fund whatever level of government spending is necessary to ensure full employment.

steve

“Even third world governments can afford to purchase anything which is for sale IN THEIR OWN CURRENCY. ” – but there ends up being nothing for sale in their own currency, including labour.

“In the short run, during a switch to MMT-inspired macroeconomic policy, exchange controls might be used to limit outward specultive flows while the new approach is being understood by market participants.” – ask South Africa how well exchange controls work: you get leakage as locals find ways to get around them, you get a grey economy operating in hard currency, local businesses don’t feel confident investing and you drive foreign investors away.

“There is no reason to raise interest rates unless you are aiming to fix the exchange rate,” – really, so with rampant inflation and currency depreciation, you don’t need to have high interest rates to encourage investment. Without raising interest rates, there is no incentive to not hold real assets.

“If there is currency depreciation, it of course implies potentially falling real incomes in the domestic economy, but that does not change the fact that a monetary sovereign government will be able to fund whatever level of government spending is necessary to ensure full employment.” You obviously haven’t been to Zimbabwe. Assuming that the economy is closed and doesn’t need to import anything. You might be able to dig and fill up holes, but try building a new airport etc without access to hard currency. I am able to finance any level of spending I like with my currency, but other participants have to be prepared to accept.

“You obviously haven’t been to Zimbabwe.”

I doubt you have, and you certainly haven’t understood the dynamics there – in particular the destruction of production by bad policy.

There are no reasoned arguments here. Just a classic game of “Why don’t you/Yes, but”.

If you don’t want to see the extra policy space MMT provides a sovereign nation then you won’t.

@neil wilson

Well, the state does have at its disposal the mechanism of eminent domain should they choose to use it, with the disadvantages that that might bring in its train, for those who misuse the opportunities the state affords such investors, such as sitting on ‘property’ that could be reused. The government doesn’t mind invoking it against individuals. A giant state-backed corporation, on the other hand, might be a cause for reflection about the consequences that could potentially be brought about by implementing such an option. But the state also has at its command mechanisms for potentially neutralizing such consequences, again if they choose to utilize or implement them. This government would no doubt allow such resources to lie idle, benefiting no one.

@ Neil Wilson

Actually I have been to Zimbabwe numerous times, as I have to most of sub-Saharan Africa. I have invested in many companies across the region over the past 15 years. I think I know a lot more about the dynamics there than you do. And have seen first hand what erosion of confidence in a government does, regardless of their magically ability to print money. The are plenty of things that work in theory that simply don’t in practice. In theory, markets are efficient and investors rational, but I see evidence every day that that isn’t true.

And there is no such thing as a sovereign nation in today global economy.

” I think I know a lot more about the dynamics there than you do.”

No you don’t – because you haven’t operated in the government or in the social services. You have seen it via the eyes of an investor and business person.

And the problems cannot be fixed from that viewpoint. Business and markets are not magic. They are just one of the many tools that need to be deployed to make a society function.