I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Off-shore tax havens – be sure we define the issues correctly

I was asked today what the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) position was on the new report about to be published by the – which reports trillions of dollars (and other currencies) being secreted in tax havens by the wealthiest citizens and the role that the top 10 banks have played in arranging these fund transfers. Progressives are clearly up in arms about the research findings and for good reason, especially if one holds equity to be a valid policy and national goal (as I do). But the way MMT analyses these trends is somewhat different. Once we get a good understanding of what the off-shoring of wealth and tax evasion actually means for domestic economies, it is clear that the progressive attacks often miss the point.

The UK Guardian article (July 21, 2012) – £13tn: hoard hidden from taxman by global elite – provided a pre-launch preview of the work done by the Tax Justice Network on the way the private banks aid the “wealthiest to move cash into havens”.

A related Guardian article (July 21, 2012) – Wealth doesn’t trickle down – it just floods offshore, new research reveals – by the same author, analysed the Tax Justice Network report in more detail.

The Tax Justice Network, in their own words, “is led by economists, tax and financial professionals, accountants, lawyers, academics and writers … and … promotes transparency in international finance and opposes secrecy … a level playing field on tax and … they … oppose loopholes and distortions in tax and regulation, and the abuses that flow from them.”

They also note that want the “owners and controllers of wealth” to fulfill their “responsibilities to the societies on which they and their wealth depend”.

In this blog I will provide both the MMT perspective and then the way I would use the MMT principles to advance what I think is a desirable policy mix. So be sure to differentiate the two. A person with quite different values and goals to my own would derive quite different policy responses to the phenomenon, including no policy response at all.

The Guardian article (first-mentioned) was provided with advance notice of the full Tax Justice Network Report, which at the time of writing had not been publicly-released.

The gist of the excellent research that the Tax Justice Network has performed is that:

A global super-rich elite has exploited gaps in cross-border tax rules to hide an extraordinary £13 trillion ($21tn) of wealth offshore – as much as the American and Japanese GDPs put together … at least £13tn – perhaps up to £20tn – has leaked out of scores of countries into secretive jurisdictions such as Switzerland and the Cayman Islands with the help of private banks, which vie to attract the assets of so-called high net-worth individuals.

The funds are largely managed by the “top 10 private banks, which include UBS and Credit Suisse in Switzerland, as well as the US investment bank Goldman Sachs”.

The Report suggests that:

<

… for many developing countries the cumulative value of the capital that has flowed out of their economies since the 1970s would be more than enough to pay off their debts to the rest of the world.

Except that the wealth and the debt obligations are not held by the same entities, which makes that sort of comparison somewhat moot. In fact, the Report tries to draw these comparisons to demonstrate how compelling their case is but, in my view, only serves to diminish their case by falsely conflating issues. More about which later.

The Report notes that these funds which “disappear into offshore bank accounts instead of being invested at home”, which is true by definition but doesn’t refine our thinking about investment.

Do they mean investment in the sense an economist such as yours truly would use the term or investment in the layperson’s language? The former relates strictly to the creation of productive capacity (plant, equipment, etc) while the latter usually relates to the purchase of financial assets or real estate.

If the alternative use of the funds that were shifted “offshore” was as investment in capital infrastructure (productive capacity) then the shift means that aggregate demand growth in the originating nation is that much lower, other things being equal.

Is that a problem? It could be.

First, it will reduce the real growth trajectory of the nations and make the nation more liable to hitting the inflation barrier (where nominal aggregate demand growth outstrips the real capacity of the economy to respond by producing real goods and services).

That is, unless the public sector fills the investment void and creates public investment goods. Then the “offshoring” (under the assumption adopted above) would see a decline in private sector activity and a rise in public sector activity.

Is that a problem? It would certainly change the composition of final goods and services produced by the economy in each period. But in a time when production has to quickly become environmentally sustainable a shift to public goods away from private goods might be beneficial, depending on the political commitment of the government to green issues.

So from an MMT perspective, there will be aggregate demand implications. Under some circumstances these might be problematic under other circumstances they will not be so.

Of-course, we were considering the funds as having two alternatives – offshore shifting of wealth or investment in real productive infrastructure.

What if the funds were never going to be invested in an entrepreneurial sense (that is, in productive infarastructure)? Then there are no significant aggregate demand issues. Domestically-held wealth portfolios would change but saving in whatever financial asset form is already lost to domestic demand – whether it be in or outside of the nation.

The notion that the “lost taxes” are in some way preventing the government from spending is just an application of mainstream economics. In terms of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) such terminology is grossly misleading.

The tax revenue lost just represents “numbers on a bit of paper” and the only issue that is important is the amount of purchasing power that is embodied in the tax cuts (or the reversal of them) and how it is distributed.

Second, these questions are in relation to (a) the need to balance nominal aggregate demand growth with the capacity of the real economy to absorb it; and (b) the aims of social policy to ensure that the benefits of economic activity are shared in some reasonable manner (relevant to the distribution of the tax burden).

The two issues are interrelated because different income groups have different propensities to consume which influences the impact of fiscal policy. Which brings the question of inequality to the fore.

The Guardian article also summarises the arguments made by the Tax Justice Network Report on inequality. They say that:

… £6.3tn of assets is owned by only 92,000 people, or 0.001% of the world’s population – a tiny class of the mega-rich who have more in common with each other than those at the bottom of the income scale in their own societies …

The Report says that these finding reveal that “inequality is much, much worse than official statistics show, but politicians are still relying on trickle-down to transfer wealth to poorer people”.

Trickle-down is a neo-liberal myth. We can agree on that. Putting spending power into the hands of those who will only save it does nothing for growth.

For more growth to occur, spending power has to be in the hands of those who spend.

But inequality is a constraint on economic growth.

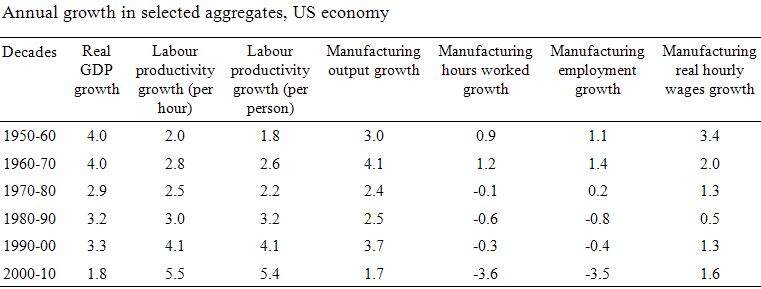

Consider the following Table that I assembled for the US (from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Bureau of Labor Statistics data) covering a period from 1950 onwards.

Real GDP growth rates have been significantly lower over the last two decades relative to the more “Keynesian” years 1950s and 1960s when entrepreneurship was more concerned with building productive capacity and putting workers to making things.

It is clear from the Table that the growth in real wages has lagged (increasingly) behind the growth in productivity. It is also clear that hours worked and persons employed in the “productive” sector has been in decline over the last few decades.

Prior to the 1970s, when neo-liberal ideas started to gain prominence, real wages growth largely tracked productivity growth which meant that as the productive capacity of the system expanded, the capacity of the workers to maintain consumption standards out of wages also grew in proportion.

There were high incomes produced but these typically came from success in building things and spreading the gains (somewhat to workers).

Now high incomes come from the financial sector capturing an increasing share of national income and using it to shuffling financial assets in the financial markets casino which adds about zero to productive output.

The funds that the Tax Justice Network are tracking reflect these dynamics. But what they are looking at is the end-point of a dysfunctional distributional system, which has to be addressed at root cause.

Tightening tax rules and closing down tax havens does not accomplish this end. What governments need to do is stop the flow of funds to the recipients in the first place.

The first thing that should be done is to change labour legislation and/or strengthen trade unions to ensure that workers can gain real wages growth in proportion to measured productivity growth.

In Australia, the wage share in national income was 62.5 per cent in the March-quarter 1975 and is now around 52 per cent in 2012. That is a staggering shift which has come about largely due to the attacks on the trade unions and their diminishing importance in the face of the rising importance of the service sector and the changing composition of the labour force that has accompanied that shift in industrial composition.

The pattern in Australia is common across many industrialised nations.

Please read my blog – A radical redistribution of income undermined US entrepreneurship – for more discussion on this point including a more detailed analysis of the US data.

The problem is that the growing gap between the real wages and productivity also violated the traditional relationship between real wages and consumption. So, if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself?

The two questions are clearly related. Marx identified the “realisation problem”, which he considered to be intrinsic to capitalism. In the past, maintaining a constant wage share helped offset this problem.

In the recent period, a new way was found to accomplish this which allowed real wages growth to be suppressed while an increasing share of national income was distributed to profits. The “realisation problem” was solved by the rise “financial engineering” which oversaw a significant escalation in debt being borne by the private sector, particularly consumers.

The rising debt underpinned the creation of a range of securitised (derivative) financial products that were deployed by the fast-growing financial sector to expand their profitability.

All components of private debt grew significantly in the decade leading up to the financial crisis which consumer debt leading the way.

While this strategy sustained consumption growth for a time it was unsustainable because it relied on the private sector becoming increasingly indebted. The strategy relied on the financial sector broadening the debt base and so riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit.

With growth being maintained by increasing credit the balance sheets of private households and firms became increasingly precarious and it was only a matter of time before households and firms realised they had to restore some semblance of security by resuming saving.

At the margin, small changes in interest rates and/or labour market status (for example, the loss of a job) pushed debtors into insolvency. Once defaults started then the triggers for global recession fired and the malaise spread quickly throughout the world.

So the underlying dynamic that generated the growth in wealth should be the focus of concern. There has to be a fundamental redistribution of national income back to wages before this situation will be addressed.

It is not clear to me that the focus on tax equity (whatever that means) is sufficient to promote the political changes necessary to make the fundamental steps that are required.

MMT models of aggregate demand build on the insights of Michel Kalecki who provided a theory of effective demand which in my view was richer than that which Keynes published a few years later in his 1936 General Theory. Kalecki’s approach had its antecedents in the earlier work of Marx, which was not surprising given that the former had been educated in Poland and was a Marxist economist before heading to the West.

In Kalecki’s work you see that effective demand (aggregate demand) is decomposed into – autonomous expenditure and induced expenditure. So there is some expenditure external to the system (for example, government policy change or export spending) which then induces further expenditure via the spending multiplier.

Please read my blog – Spending multipliers – for more discussion on this point.

The multiplier is based on the insight that the change in induced spending grows by a smaller rate than the initial autonomous spending injection that motivated it. This is because consumers save a proportion of each extra dollar they receive.

The interesting insight that Kalecki introduced into his work was to include a consideration of the distribution of income between wages and profits. So the most basic models assumed that workers saved nothing and profit recipients saved everything. The more sophisticated models in this class allowed workers to save some amount of their extra wages but still have a higher propensity to consume than profit recipients who were also assumed to save some proportion of their income.

In other words, a redistribution of national income can increase or decrease aggregate demand. Kalecki’s insights, in my view, provided more advanced understandings than those offered in the General Theory (Keynes deals with the Propensity to Consume and the Multiplier in Part III, Chapters 8-10. They are worth your time reading.

When considering the aggregate demand impacts of the change in tax rates (an extension or not), the final impact thus depends on the different consumption propensities and the number of people who are affected.

It is not a straightforward case to argue that the rich don’t spend as much so therefore the demand effects of taking away the extension will not damage the overall level of demand.

There is an additional factor to consider. This relates to the discussion above about the two components of a change in aggregate demand following a policy variation.

For example, a tax cut will inject a certain amount of extra spending into the economy which then induces further spending via the multiplier process. In the blog – Spending multipliers – I note that the multiplier is higher the higher the propensity to consume, the lower the tax rate and the lower the propensity to import.

Imports comprise a leakage from the expenditure stream for income generated by the domestic production process. Just as the overall propensity to consume is dependent on the distribution of income, the overall propensity to import is also sensitive to income distribution. It is highly likely that the higher income groups have a higher propensity to import (per dollar of extra income) than the lower income earners.

So what does that mean? It means that if you put a dollar of extra disposable income into the hands of the lower paid workers the multiplier effects will be greater than if you put the extra dollar into the hands of high income earner because less will be lost to the rest of the world via imports.

Not only will the low income earners spend more of every extra dollar on consumption per se than the high income earners less income will be lost to the rest of the world because the import propensities are also different and align with their consumption propensities.

While it might be sensible to redistribute income away from the high-income recipients towards lower income workers on equity grounds and this might increase aggregate demand somewhat, the overall problem of mass unemployment is that the budget deficit is too small per se.

Couching the arguments about off-shoring of wealth in terms of the “impact” on budget deficits – such that the government could get the deficit under control more easily if the rich paid more taxes – misses this point.

That implies an intrinsic financial constraint on currency-issuing governments which from an MMT perspective is an invalid concern. It is clear that there are political constraints on government deficits and that is the problem that has to be addressed.

Finally, what about the lost tax revenue, which is a major theme of the Tax Justice Network?

The Guardian quotes the Report as saying:

The problem here is that the assets of these countries are held by a small number of wealthy individuals while the debts are shouldered by the ordinary people of these countries through their governments.

You will immediately detect some mainstream economic constructions here – the type which leads anti-government lobbies to divide the total public debt by the population and put up debt clocks to tell us how much each man, woman and child owes in public debt.

The reality is quite different. I don’t owe any of the debt that the Australian government currently has outstanding.

The point made by this association is that the debt has to be paid back and so that is a burden on taxpayers. That claim is also spurious. In general, governments do not pay their debts back by levying higher tax rates. And if they are claiming to be doing that when they do increase tax rates then they are misleading the populace.

Levying higher taxes certainly lowers the purchasing power of those who are paying the taxes and progressives argue that the burden of this lost purchasing power should be spread across income recipients.

Saying that the rich should pay might make progressives feel better but it doesn’t face up to the real problem – a need for fundamental re-education of the public about the role of the budget deficit and the status of currency-issuing governments. That is where the progressive effort should be focused.

In that vein, the Guardian quoted the UK Trade Union Council general secretary who fell prey to the orthodox line of thinking:

Countries around the world are under intense pressure to reduce their deficits and governments cannot afford to let so much wealth slip past into tax havens … Closing down the tax loopholes exploited by multinationals and the super-rich to avoid paying their fair share will reduce the deficit. This way the government can focus on stimulating the economy, rather than squeezing the life out of it with cuts and tax rises for the 99% of people who aren’t rich enough to avoid paying their taxes.

What he might have said is that when tax revenue is higher there is more “room” for government spending, not because the government has more money to spend, but because there is more real productive capacity to absorb via nominal spending. But of-course, it is unlikely that the funds that have been “lost” to off-shore destinations would have been spent anyway.

Conclusion

I haven’t time today to provide further analysis of what the flow of funds across borders might mean for the balance of payments and exchange rates. That will have to wait for another day.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

Aren’t a lot of ïnvestments in places like Luxemburg and Switzerland illusory, comparable to the ships registered in countries like Liberia and Panama. The ships registered in Liberia and Panama aren’t owned by Liberians and Panamanians and don’t necessarily employ the citizens of those countries either. Similarly, wealth transfered to a bank in a tax haven is not invested there. Suppose that I own 100 million in financial assets. Instead of depositing in a Canadian bank, I deposit it in a bank in Luxemburg. What is the Luxemburgian bank going to do? Lend it all to Luxemburgers? No, there is only so much that half a million Luxemburgers can borrow. Nearly all the money deposited in Luxemburgian banks is lent to people outside of Luxemburg. Ultimately, there is no financial wealth, only real wealth. If all real wealth in the world were destroyed, financial wealth would become zero.

Regardss. James

” Suppose that I own 100 million in financial assets. ”

Don’t forget that denominations matter. Generally you can only exchange denominations, not convert them. And that is important.

If you transfer Canadian Dollars to a bank in Luxembourg, then it matters what you are buying from the bank and what it is denominated in. Because that will set off another train of transactions to hedge the instrument.

It may be as simple as exchanging the Canadian Dollars for Euros with somebody going in the opposite direction. In which case all that happens when you transfer out of Canada is that your dollars end up in the hands of somebody transferring in and macro economically that the same as you not transferring at all.

One of the things that annoys me about these reports is that they assume ‘foreign’ is a magical place where the economic rules don’t apply – rather than another entity like your country operating in the same ‘one planet’ constrained environment with only so much policy room.

It’s mostly about using the ‘fear of foreign invaders’ narrative to push an angle.

Too bad Bill didn’t have time to discuss the effects on currency. I was thinking of Russian oligarchs exchanging their accumulated roubles into billions of euros, pounds and dollars. Surely that puts downward pressure on the rouble so ordinary Russians are denied imports at a respectable prices.

Technically they may not even need to exchange roubles as the money can come from selling Russian resources in US dollar denominated contracts. It has the same negative effect for Russian consumers as those US dollars would otherwise have been exchanged for roubles.

The oligarchs have no intention of spending their billions in Russia. There are nicer toys to play with in Europe and the USA. The funds are permanently lost to Russia. How sad for ordinary Russians, to see their once common resources buying English premier league teams for gangsters.

Here in Australia we have a handful of billionaire owners, rich investors and mining execs whooping up the jet set lifestyle on the back of our national resources being sold to China. At the same time we have a ton of corrupt Chinese officials buying up whole suburbs for their extended families. At least it kind of balances out. What a crazy world we live in.

The longer this craziness goes on the more I see nationalisation and/or mutualisation of corporations as the most valid response. Too bad the ALP are merrily steaming completely in the wrong direction.

Dear Dr. Mitchell,

I understand your point of the primary problem being that budget deficits are too small, and agree. But I think that how that money is spent plays a critical role in effectiveness. Much of U.S. spending ends up as corporate profits rather than disposable income for workers, attenuating the efficacy of budget deficits. I think that aiming stimulus directly at households via direct wage supplements would be far more useful than large, capital intensive programs. In this case there are no middlemen to reduce the flow of funds to consumers.

Regarding:

“It is highly likely that the higher income groups have a higher propensity to import (per dollar of extra income) than the lower income earners.”

This may be empirically true – I assume that it is because Bill says so. I don’t understand why. Those fleets of container ships sure bring a lot of imported stuff to America – to be sold at Sam’s, Costco, Target and Wal-Mart. Not exactly jet-set venues…

Dear Bill,

I apologise for asking such a basic question, but it was my (faulty?) understanding that dollars couldn’t leave the US banking system. So are these hidden savings, dollars that has been swapped into another currency, or do they remain within the US banking system, but within entities which have different reporting requirements compared to the onshore banks? (Or maybe they are foreign earnings that have never been on-shored?). I couldn’t see this information in the Guardian report.

It still amazes me that anyone can believe government deficits can increase wealth. Every dollar a government spends, borrowed or taxed, can only ever transfer wealth around the economy. It can never actually produce anything. Nor can the transfer lead to greater productivity than had the transfer not occurred, since, for one thing, the government redistribution always requires a large army of bureaucrats who produce no wealth of their own, merely consuming the wealth produced by others.

@Reinhard,

When a sovereign government runs deficits it is not redistributing from one group to another, it is adding new net financial assets to the non-government sector. The actual process is relatively complicated, involving a series of credits and debits between the central bank and treasury, but the end result is the same. It is not transferring wealth it obtain from taxation because the private sector is not the originating source for the national unit of account.

Dale,

It’s true even the poorest do seem consume a load of cheap imports tjese days. A lot of basics like food are home grown though. Most of the really luxurious items are imported right… Expensive French perfumes, Italian marble, German cars, gold and diamonds. When the jet set travel abroad for 6 moths of the year spending millions of dollars on foreign stuff… that is functionally the same as importing.

@Reinhard,

“Every dollar a government spends, borrowed or taxed, can only ever transfer wealth around the economy”.

That is true only if the economy is at full employment.

If productive resources are unemployed – which is the case, and massively so, in the present crisis – then (to use Kalecki’s immortal words) “the effective demand created by the Government acts like any other increase in demand. If labour, plant and foreign raw materials are in ample supply, the increase in demand is met by an increase in production”.

Kalecki then went on to add: “But if the point of full employment of resources is reached and effective demand continues to increase, prices will rise so as to equilibrate the demand for and the supply of goods and services”.

With such a clear and concise explanation available for all to read since the year 1943, it is hard to understand why so many people still have difficulty in accepting the case for public deficit spending.

How about this for an argument?

Suppose a UK citizen, Mr Smith, has one billion pounds spare that he wishes to save. Firstly, suppose he puts it into a Swiss bank and gets a certain interest on it. Presumably, he would not have to pay tax on the interest, which is a gain for him (and a loss for the UK government if the alternative is to deposit the money into a UK bank). It doesn’t matter to him or the UK what the Swiss bank does with the money (unless perhaps it is using it to make dealings within the UK). Moving a deposit from the UK to Switzerland might make a difference to the UK bank if it does not have enough reserves and has to borrow some money elsewhere to replace it or somehow attract more deposits. This might or might not be more expensive for it.

Suppose instead, Mr Smith leaves his money in a UK bank. He would still get some interest but he then has to pay tax to the UK government.

It seems to me that the only serious difference to the UK is whether the tax is paid, and if the tax is paid in the UK it makes more space for the UK government to spend. The only moral issue is to do with tax avoidance.

@Reinhard

What’s even more amazing is the financial sector can absorb up to 20% of national GDP without producing one single item of real wealth. Inefficient middlemen, leeching off genuinely productive endeavours, transferring others money around and skimming into their own pockets. There are hundreds of thousands of them doing exactly nothing useful.

Dear Reinhard,

just keep on reading this blog and one day you will get it.

Tony,

Paying more tax doesn’t neccessarily “create more space” (or increase the neccessity) for the Government to spend.

If Mr Smith was saving the taxable interest it would not have been spent anyway. It would not become someone else’s income and would not add to demand. Taxing his interest will make no difference to the economy.

If Mr Smith was in the habit of spending the taxable interest. Taxing him would reduce demand, the government should then spend more to make up the demand deficiency.

Is it just me, or are there fewer and fewer Reinhard comments these days and more constructive discussion?

Is this what that first little ounce of traction feels like?

@dnm

I’ll take a swing at this one.

First, dollars definitely circulate in very large quantities among foreign banks, firms and individuals. Foreign central banks also hold dollars (in cash accounts, as opposed to dollar-denominated T-bonds). Foreign entities need dollars to pay for dollar-denominated imports such as oil. They get them from companies which export to the U.S. and who, therefore, get paid in dollars. The (for example) Chinese exporters bring their dollars to the Central Bank of China, where they swap them for yuan to pay out in wages and to cover their other local bills. The central bank has lots of choices, but a common one is to take those dollars and buy T-bonds.

This is, of course, voluntary. The motivation is both to get a modest, risk-free interest payment and also to build up dollar reserves to help stabilize their own banking and financial system. This is what the “national debt clock” in New York City really measures – the worldwide demand for dollar-denominated financial assets. One of America’s roles in the world is to supply this liquidity. One side effect is that as long as this system continues, we are forced to run trade deficits to the exact extent of the demand for reserves. MMT shows that these favorable “real terms of trade” greatly benefit American consumers and represent real costs for China and others. We get oil, automobiles, toaster ovens, etc. and they get something – dollars – that we create by fiat on a computer screen.

The demagoguery on this from all points on the media political spectrum is a direct result of the near-universal macroeconomic illiteracy of our elites. Whenever anyone says “they’re shipping our jobs to China!”, whether it’s Bernie Sanders or Mitt Romney, take a deep breath and repeat Mosler’s Law: “There is no financial crisis so deep that a sufficiently large tax cut or spending increase cannot deal with it.” The U.S. government *always* has the ability to end a recession and restore full employment. There is nothing China or anyone else could do to stop this from happening, and no reason why they would want to.

This subject, and many other very interesting ones, is covered, in exacting detail, by friend-of-MMT economist James Galbraith in his indispensable book “The Predator State”.

Cheers

Bill –

I’m not saying the strategy didn’t result in a broadening of the debt base, but I think it’s a bit of a stretch to say it relied on doing so. Surely if the debt base had not been broadened, governments and central banks would have reacted by cutting interest rates which would result in a deepening of the debt base as longer term business investment became more viable?

Bill –

Are you sure that’s the reason?

How does the rise in business to business transactions affect the figure?

Do you have a component breakdown of the non wage share?

Other than regulating/deregulating prices and promoting competition, is there anything that could be done to control/reduce inflation by reducing the non wage share in absolute terms?

@Dale

Thanks for your reply. I had forgotten to exclude cash from my question! It’s obvious that banknotes can travel anywhere. However the thing that you are claiming, that e.g. the central bank of China can hold dollar reserves, is precisely the thing that I had understood to be impossible. I’ll not be able to get my mitts on a copy of Predator State any time soon. Do you know of any on-line source that explains these matters?

@dnm

Regarding a foreign central bank holding dollars, you can read Mosler’s, The Seven Deadly Innocent frauds of Economic Policy, http://moslereconomics.com/2009/12/10/7-deadly-innocent-frauds/. The first section discusses trade deficits and dollars in foreign banks in straightforward language. The dollars I spent on my TV end up in China, eventually in the Bank of China, in their account at the Fed. They can hold the dollars, spend them or switch them to an interest-bearing account at the Fed (a T-bill,bond, or note). You can also search this blog for articles on central banks, trade deficits and banking operations.

If wealth becomes concentrated, there is less demand because the people who spend a large share of their income have less to spend. So, there are fewer good places for the wealthy to invest. So they turn to speculation (dot coms, housing, shale gas) trying to earn more (or the financial engineers use something like housing to create high-yielding investments). These bubbles then suck in a portion of the middle class who often use debt to invest … finally kablooey.

Opinions on this theory?

Sounds good to me Steve.

It still amazes me that anyone can believe government deficits can increase wealth. Every dollar a government spends, borrowed or taxed, can only ever transfer wealth around the economy. It can never actually produce anything.

There is no reason at all that public investment should not generate the same or a greater bang for the investment buck than an equal amount of private investment. Public investment can also lead to increases in productivity if, for example, it takes place in the area of education. … Or information technology, an obvious recent example. The historical evidence of the massive role of public investment in economic growth is overwhelming and obvious.

Andrew,

When I said that the tax would “make for space for government spending”, I was parroting what is often said, I think by Bill himself. Without the government’s need to have money before it can spend, which I can understand, the reasons for taxation that I have read are (a) that it makes space for spending and (b) that by taxing in the official currency, it forces people to earn money in that currency to pay their taxes and hence establishes the currency. I can’t believe that there is not more to the question than those two things. For example, taxation and government spending both are tools to redistribute money and spending.

We are told that excess government spending is good when there is unemployment and that too much government spending, e.g. when there is full employment, causes inflation. Intuitively, it seems bad to have government spending when there is no taxation, although it is not clear, to me at least, what the ultimate effect of that would be. I would like to see some better economic modelling around this question.

If paying extra tax makes no difference to the economy, why should I bother paying tax at all?

When Reinhard says “Every dollar a government spends, borrowed or taxed, can only ever transfer wealth around the economy”, it is true if the government’s budget is balanced, as he suggests, and wealth refers to money alone. But that could be a desirable outcome and it could very well have a beneficial effect on the real wealth of the economy.

Tony,

I hear what you’re saying and mostly agree.

Hopefully to clarify my point. Taxing savings has little impact on demand so it doesn’t create a lot of space for Government spending. Taxing income has a greater impact on demand.

” Taxing savings has little impact on demand so it doesn’t create a lot of space for Government spending.”

It doesn’t reduce real demand very much. However it does have some uses. If you’re a strange character that is worried about increasing the amount of liabilities a central bank creates then taxing savings allows you to create a new stock of liabilities in the hands of the government while destroying old ones in the hands of the non-government sector.

So it would allow certain political types to continue practising their religious beliefs.

” Intuitively, it seems bad to have government spending when there is no taxation, although it is not clear, to me at least, what the ultimate effect of that would be.”

Intuitively it may do, but bear in mind that assumes that the non-government sector can get to full output by itself. The paradox of productivity suggests otherwise. In an economy where all the labour isn’t required to produce sufficient output it is irrational for the private sector alone to produce sufficient output. In that situation the government has to pump prime to get the output up to maximum in the first place.

So essentially in a productive economy where the paradox of productivity applies there is a certain amount of ‘free’ spending room available for the government. So you could say that the police force, the military and the tax collectors pay for themselves.

I don’t think anyone has answered dnm’s question.

Romney’s $100 Million(?) stash in the SwissBank was not the result of any sort of current account trade balance.

Are we saying that it is in the SwissBank’s account at the Fed?

No, because then we’d know what it was.

Bill says he cannot “” provide further analysis of what the flow of funds across borders might mean for the balance of payments and exchange rates “”.

So, a great, simple question, dnm.

And, a little disappointed that MMT is not more circumspect about the ‘free flows of capital (currencies)’ that can only provide leakage to national full-employment efforts.

I hope Bill will provide further analysis when time allows.