I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

A radical redistribution of income undermined US entrepreneurship

There was an Bloomberg Op Ed today (November 22, 2011) – Protesters Ignore American Love of Entrepreneurs – by Harvard economist Edward Glaeser. It is an attack on the OWS movement and an appeal to how great American entrepreneurship is. The ideas resonate with some recent work I have been doing on the impacts of national income redistribution under neo-liberalism on aggregate demand and the role of the financial sector. The link is that entrepreneurship in the US is not what it was and it is an illusion to think that the past two decades or so bears much similarity to the heyday of US entrepreneurship, whatever your view of the latter is. The entrepreneurs are disappearing in American and being replaced by rapacious wealth shufflers who add nothing to productive capacity or general prosperity.

I was talking to one of my PhD students about the way nomenclature is used in different ways. When an economist talks about “investment” – the term is being used to describe the flow of spending that is aimed at augmenting productive infrastructure – more equipment, buildings etc.

Buying a government bond or a share in a listed company is not investing to an economist. Entrepreneurs invest, hedge funds rarely invest. That distinction helps to understand why the Glaeser article misses the point.

Glaeser asserts that:

The Occupy Wall Street movement is fighting an almost unwinnable battle against the ghost of Steve Jobs.

America’s love affair with entrepreneurship complicates any attempt to mount an effective European-style war of have-nots against haves. To be successful, the new economic populists must connect their message with the American embrace of those, like Jobs, who become rich by improving our economy and the world.

While the OWS movement and the related general anger in the community might be, in part, a cry about income inequality and high incomes per se I consider it to be much broader than that.

I don’t just see the “Occupiers” as being “angry that President Barack Obama didn’t do more to eliminate the inequities of American life”. I see them angry about an elite that has hijacked the economic system and made it work less productively than before while redistributing more of what is working to themselves. So it is not just a distributional issue.

Glaeser seems to think that the OWS movement is pushing for a “far more expansive view of state intervention embraced in continental Europe” and are oblivious to the US sentiment that supports “America’s generally limited government”. He says that their “hopes ignore the profound historical forces that have limited social democracy and redistribution in the U.S.”

He then promotes a book he wrote with fellow free market (anti-government) academic (Alberto Alesina) which waxes lyrical about how wise the US founding fathers were to insulate the nation from as he says – “leftward tilts”.

He then quotes some survey results which tell us that:

1. “60 percent of Americans believe that the poor are lazy, a view shared by only 26 percent of Europeans”.

2. “30 percent of Americans believed that luck determines income, and 54 percent of Europeans had that opinion”.

3. “36 percent of Americans agree that “success in life is determined by forces outside our control,” and 62 percent disagree. By contrast, 72 percent of Germans and 57 percent of the French take the view that outside forces determine success”.

4. “58 percent of Americans, but only 36 percent of Germans, believe that “freedom to pursue life’s goals without state interference” is more important than that the “state guarantees nobody is in need.””

He considers that the differences reflect the “decades of left-wing political success in Europe that have led to promulgation of views that support the welfare state. Paradoxically, American children are taught that they live in a land of opportunity despite the fact that economic mobility is actually higher in Germany than in the U.S.”

Perhaps all of that is a sound representation of the state of the American psyche. But then when one starts eulogising about the “Entrepreneurial Model” the problems begin to run counter to the data.

He talks about the success of US entrepreneurs in comparison with the “dominance of the European aristocracy”, the latter who “do little to justify their luxuries”. The US success stories apparently “earned their billions with ingenuity and effort”.

He admits that entrepreneurship is threatened in the US but concludes that he fears that:

… a radically more redistributive state, resembling the one championed by the Occupy Wall Street movement, would damage the entrepreneurial spirit that has, for so long, been such an exceptional American strength.

The reality is that the state has already engaged in radical redistribution which has been associated with the decline in the “entrepreneurial spirit” and the success of the entrepreneurs.

I refer to the rise and now dominance of the neo-liberal era that has seen a dramatic redistribution of national and personal income in favour of profits and the rich but has also been associated with a dramatic decline in the performance of the US economy.

Perhaps, all that the OWS movement hankers after is the time – long past – when the US economy created wealth and opportunities for all Americans and didn’t produce to support a small enclave of extremely wealthy Americans who spend their time unproductively shuffling wealth.

Perhaps the OWS want is some guarantees that this cohort will in some way be held responsible for their behaviour and the spillovers which have undermined the wealth of millions and impoverished even more.

The US Congressional Budget Office provided very interesting data Additional Data on Sources of Income and High-Income Households, 1979-2005 – which reveals that in 2005, the top 1 per cent of Households on average earned $US24,286,300 (post tax) while the bottom quintile earned $US15,300 on average. The second quintile earned $US33,700, the third $US50,200; the fourth $US 70,300, and even the second last percentile earned on average $US3,191,600.

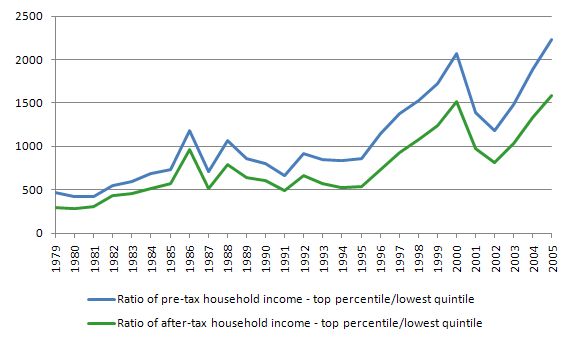

The following graph shows the ratio of the average household income for the top percentile to the lowest quintile between 1979 and 2005 for pre-tax and after-tax income.

In 1979, families in the top quintile received 467 times the income received by families in the bottom 20 per cent of the distribution (291 times after tax).

By 2005, the ratio had risen to 2231 (and 1587 after tax), a staggering shift.

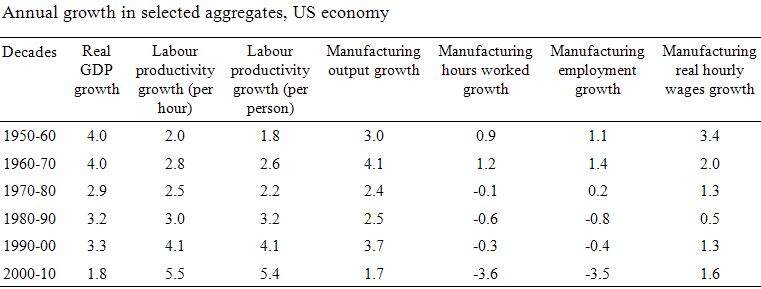

Further, consider the following Table that I assembled which bears on the performance of the entrepreneurs in the US over the last 60 odd years.

Real GDP growth rates have been significantly lower over the last two decades relative to the more “Keynesian” years 1950s and 1960s when entrepreneurship was more concerned with building productive capacity and putting workers to making things.

It is clear from the Table that the growth in real wages has lagged (increasingly) behind the growth in productivity. It is also clear that hours worked and persons employed in the “productive” sector has been in decline over the last few decades.

Prior to the 1970s, when neo-liberal ideas started to gain prominence, real wages growth largely tracked productivity growth which meant that as the productive capacity of the system expanded, the capacity of the workers to maintain consumption standards out of wages also grew in proportion

There were high incomes produced but these typically came from success in building things and spreading the gains (somewhat to workers).

Now high incomes come from the financial sector capturing an increasing share of national income and using it to shuffling financial assets in the financial markets casino which adds about zero to productive output.

And when these gamblers stuff up – after cheating, lying, double-dealing and whatever else was involved – they plead for bailout support from the state. All private gains, all socialised losses.

The discontent associated with the from the general public, is, in part, what I think the OWS movement is trying to articulate. They might not yet have enough conceptual ammunition to present an alternative but with millions unemployed and bank bonuses still being paid the contrast is rather stark.

If we think back in history – the “left” (as it is) in the US were in control of America during and after the Great Depression for more than 3 decades. The economy boomed (with cycles) and real wages kept pace with productivity.

By contrast, the neo-liberal years have resulted in fairly poor outcomes and have culminated in the worst economic disaster since the Great Depression.

I think Edward Glaeser is writing in a time warp. Entrepreneurship in the US is now swamped by the financial market gamblers.

There is an interesting Bureau of Labor Statistics paper in the January 2011 edition of the Monthly Labor Review – The compensation-productivity gap: a visual essay – by BLS staff Susan Fleck, John Glaser, and Shawn Sprague.

They examine what they term to be the “compensation-productivity gap” in the US which is the difference between the growth in real wages and labour productivity. They argue that (Page 1):

Productivity and compensation measures yield information on the extent to which the employed benefit from economic growth. Productivity growth provides the basis for rising living standards; real hourly compensation is a measure of workers’ purchasing power … Employers’ ability to raise wages and other compensation is tied to increases in labor productivity. Since the 1970s, growth in inflation-adjusted, or real, hourly compensation has lagged behind labor productivity growth.

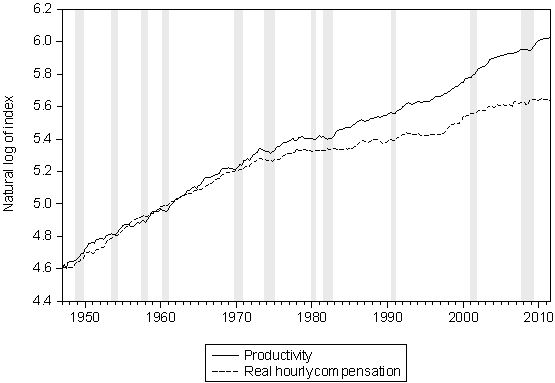

The following graph is taken from a paper I have just completed with Joan Muysken (available in working paper form soon) and shows the movement in productivity (output per hour worked) and real hourly compensation in the US from the first-quarter 1947 to the third-quarter 2011. The data is sourced from the US Bureau of Labour Statistics Major Sector Productivity and Cost database.

Labour productivity is real non-farm business output divided by the total hours worked and real wages are the total real hourly wages, salaries, and benefits paid to workers in the non-farm business sector. The data is seasonally adjusted. The time series are indexed to 100 at the start of the sample and the indexes are expressed in log format to “ensure constant proportionality of the growth of each index across time” (see Fleck et al., 2011: 2).

There are both cyclical and trend factors evident in the evolution of the time series. Labour productivity tends to be pro-cyclical (as a result of hoarding).

The shading is based on the business cycle data provided by the US National Bureau of Economic Research and denotes the peak to trough which define the recessionary period. The NBER shading is included to highlight the cyclical behaviour of each series.

In addition, it is clear that while both series have been trending upwards over the sample, the divergence between productivity and real wages has widened since the mid 1970s. The widening productivity-compensation gap evident in the graph is a common feature of many advanced economies.

The widening compensation-productivity gap means that the wage share – “the share of output accounted by employee’s compensation” (Fleck et al, 2011: 1) – has been falling.

Fleck et al. (2011: 1) say that the wage share is:

… a measure of how much of the economic pie goes to all workers. When labor share is constant or rising, workers benefit from economic growth. When labor share falls, the compensation-productivity gap widens. Concurrently, nonlabor costs-which include intermediate inputs into production and returns to investments, or profits-represent a greater share of output.

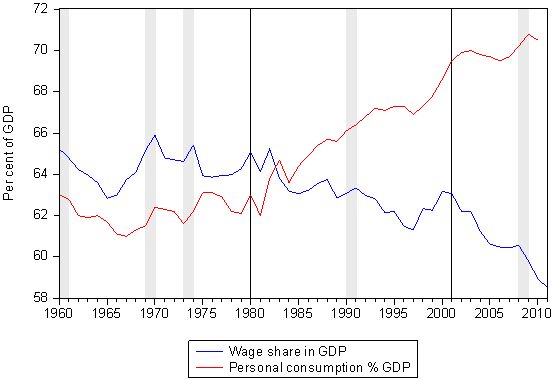

The following graph shows the share of US wages in gross national output for the period 1960 to 2011. Once again the cyclical movements (wage share tends to rise in a recession as productivity growth declines faster than the growth in real wages) are evident as is the trend decline.

The data is taken from the Eurostat AMECO database and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Production Accounts database and the shading is the NBER cycles.

The declining wage share over the last three decades or so is a common feature of most advanced economies. Prior to the mid-1970s, the constancy of the wage share in national income, as a result of the close relationship between labour productivity and real wages growth, was one of six stylised facts of capitalist economic growth identified by Cambridge University (UK) economist Nicholas Kaldor in 1957.

I also superimposed the share of Personal Consumption in GDP (per cent) from 1960 to 2010 onto the wage share. About the time, the wage share started to decline (early 1980s) the share of consumption in GDP grew rapidly.

The data makes it clear that the declining wage share was not associated with a higher investment ratio. The question that arises, given these trends, is how did the consumption share rise so significantly at the same time as real wages growth was largely flat and the share of wages in national income was falling?

A further question is also suggested from the data. As noted above, the growing gap between the “two shares” violated the traditional relationship between real wages and consumption. So, if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself?

The two questions are clearly related. Marx identified the “realisation problem”, which he considered to be intrinsic to capitalism. In the past, maintaining a constant wage share helped offset this problem.

In the recent period, a new way was found to accomplish this which allowed real wages growth to be suppressed while an increasing share of national income was distributed to profits. The “realisation problem” was solved by the rise “financial engineering” which oversaw a significant escalation in debt being borne by the private sector, particularly consumers.

The rising debt underpinned the creation of a range of securitised (derivative) financial products that were deployed by the fast-growing financial sector to expand their profitability.

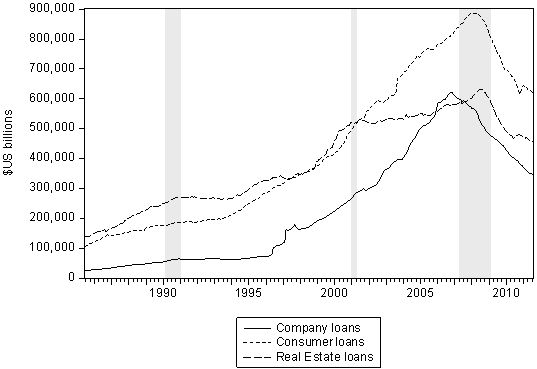

The following graph shows the evolution of private credit in the US from 1985 onwards using data available from the US Federal Reserve Bank. The data covers corporate, consumer and real estate credit from all finance companies and is available monthly from June 1985 ($US billions, seasonally adjusted).

All components of private debt grew significantly in the decade leading up to the financial crisis which consumer debt leading the way.

The household sector, in particular, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing federal surpluses during the Clinton era, were enticed by lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers to borrow increasing amounts.

Part of the real income that was redistributed to profits was also the source of the dramatic escalation of executive pay and financial market bonuses that have been documented over the last few decades in most advanced economies.

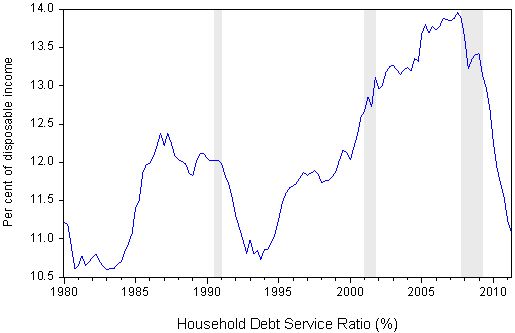

The following graph shows the Household Debt Service Ratio (DSR) published by the US Federal Reserve.

The DSR “is an estimate of the ratio of debt payments to disposable personal income. Debt payments consist of the estimated required payments on outstanding mortgage and consumer debt”.

The DSR peaked at 13.96 per cent in the third quarter 2007, just before the crisis emerged.

The related series – the Financial Obligations Ratio (FOR) – which “adds automobile lease payments, rental payments on tenant-occupied property, homeowners’ insurance, and property tax payments to the debt service ratio” follows the same sort of pattern and also peaked at 18.85 per cent in the third quarter 2007.

While this strategy sustained consumption growth for a time it was unsustainable because it relied on the private sector becoming increasingly indebted. The strategy relied on the financial sector broadening the debt base and so riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit.

With growth being maintained by increasing credit the balance sheets of private households and firms became increasingly precarious and it was only a matter of time before households and firms realised they had to restore some semblance of security by resuming saving.

At the margin, small changes in interest rates and/or labour market status (for example, the loss of a job) pushed debtors into insolvency. Once defaults started then the triggers for global recession fired and the malaise spread quickly throughout the world.

In our paper we argue that aggregate consumption demand is sensitive to the distribution of national income (factor shares) and that the US economy was able to continue growing in the period leading up to the financial crisis despite a major erosion of the wage share because of the expansion of credit.

We also argue that these dynamics were directly responsible for the financial and then real crisis that emerged in 2007.

I will provide more discussion about our econometric and mathematical model in another blog.

Conclusion

The neo-liberal redistribution of national income instigated by the financial market lobbying of the US Congress has served to undermine US entrepreneurship.

The OWS movement intrinsically knows that that the America of old is defunct and an elite of bankers has taken over the economy and use it to gamble – often winning spectacular amounts but, equally sometimes losing.

The gambling elites have arranged things so that the losses are all borne by the masses while the gains have been increasingly privatised. More US economic activity is now described in this way rather than the “glory” days of classic US entrepreneurship in the 1950s and 1960s.

That is enough for today!

If I haven’t overlooked a past blog post, I wouldn’t mind seeing the:-

Annual growth in selected aggregates, Australian economy

in a future post

Even so, I have friends who refer to themselves as “entrepreneurs” and seem to do ok for themselves. They’ve found little niches in which to specialize and offer services, or sometimes tangible products. A couple of them are one man shows. And of course their attitude toward the unemployed is: If I can do this, so can you! In America, you can create your own job! What’s wrong with you?

They are, of course, invariably minimal gov’t libertarian types. Where do these folks fit in to the scheme of things, according to MMT/Keynes/Marx/whoever? How to answer them? “No, you’re wrong …. not everybody can be you.” … is the answer that comes to mind, but looking for something better … hard to deny their at least apparent success. Although my feeling is it can’t really scale.

@Ken

There are those who do say the sorts of things you mention and it may be no fault of their own that they do not see that their argument is invalid in the large. It is analogous to pointing to a successful kid from a poverty stricken environment as evidence that anyone can lift themsleves from poverty. The assumption is that one’s achievements are due virtually entirely to one’s own intitiative. The conclusion that is inevitably drawn is that failure to do similarly is an individual failure. Such views are based on fantasy. A consideration of the historical data does not support these views. While there are exceptions like the successful kid from a poverty stricken environment, the general rule is that successful initiatives are enabled by others, such as family or a social institution.

Ken,

I’d say about 90% of ‘Entrepreneurs’ are dependent on Govt at least indirectly. To challenge them just ask them do they use a computer. Then ask them where the transistor came from. Do they fly in jet aeroplanes? Ask if they advertise or otherwise use the internet or a mobile phone. Then ask them where all these came from to create their ‘Libertarian’ paradise. If they are intellectually honest they’ll soon discover that in reality this type of small service sector they provide is dependant on huge industry (Which is always either directly or indirectly run by Government) which they satellite around.

In many cases the activity of your friends may be even more directly linked to government run or heavily subsidised companies than just using products designed in government protected envirnoment.

Check out ‘Steal this Idea’ by Michael Perelman or the ‘Conservative Nanny State’ by Dean Baker too.

Kaiser

Every other time I come across an economist talking B.S. it turns out to be a Harvard economist: Rogoff, Martin Feldstein, Alberto Alesina, and now Edward Glaeser. What’s wrong with the place? Seems those Harvard economics students who refuse to attend lectures have a point.

If there were more competition for one man entrepreneurs in their niche market, prices earnings and their living standards would fall.

It’s a fallacy of composition and in aggregate the weak demand and cold sub-optimal state of the economy limits all our options.

Any businessman, one man entrepreneur or transnational should be keen on higher deficits as they mean there’s more money demand to make profits from.

@Larry

Good post, I was going to say something similar , the types of people ken referred to usually come from middle class backgrounds and therefore have been fortunate enough to be given a good place to start from, most of the heavy lifting has already been done for them by previous generations.

Anyway I recently found this speech from a Scottish trade unionist called Jimmy Reid , which he delivered on his inauguration as rector of Glasgow University in 1972, so much of it seems relevant to recent times so I thought I put it up for people to read, I hope you don’t mind the length of it Mr Mitchell.

“Alienation is the precise and correctly applied word for describing the major social problem in Britain today. People feel alienated by society. In some intellectual circles it is treated almost as a new phenomenon. It has, however, been with us for years. What I believe is true is that today it is more widespread, more pervasive than ever before. Let me right at the outset define what I mean by alienation. It is the cry of men who feel themselves the victims of blind economic forces beyond their control.

It’s the frustration of ordinary people excluded from the processes of decision-making. The feeling of despair and hopelessness that pervades people who feel with justification that they have no real say in shaping or determining their own destinies.

Many may not have rationalised it. May not even understand, may not be able to articulate it. But they feel it. It therefore conditions and colours their social attitudes. Alienation expresses itself in different ways in different people. It is to be found in what our courts often describe as the criminal antisocial behaviour of a section of the community. It is expressed by those young people who want to opt out of society, by drop-outs, the so-called maladjusted, those who seek to escape permanently from the reality of society through intoxicants and narcotics. Of course, it would be wrong to say it was the sole reason for these things. But it is a much greater factor in all of them than is generally recognised.

Society and its prevailing sense of values leads to another form of alienation. It alienates some from humanity. It partially de-humanises some people, makes them insensitive, ruthless in their handling of fellow human beings, self-centred and grasping. The irony is, they are often considered normal and well-adjusted. It is my sincere contention that anyone who can be totally adjusted to our society is in greater need of psychiatric analysis and treatment than anyone else. They remind me of the character in the novel, Catch 22, the father of Major Major. He was a farmer in the American Mid-West. He hated suggestions for things like medi-care, social services, unemployment benefits or civil rights. He was, however, an enthusiast for the agricultural policies that paid farmers for not bringing their fields under cultivation. From the money he got for not growing alfalfa he bought more land in order not to grow alfalfa. He became rich. Pilgrims came from all over the state to sit at his feet and learn how to be a successful non-grower of alfalfa. His philosophy was simple. The poor didn’t work hard enough and so they were poor. He believed that the good Lord gave him two strong hands to grab as much as he could for himself. He is a comic figure. But think – have you not met his like here in Britain? Here in Scotland? I have.

It is easy and tempting to hate such people. However, it is wrong. They are as much products of society, and of a consequence of that society, human alienation, as the poor drop-out. They are losers. They have lost the essential elements of our common humanity. Man is a social being. Real fulfilment for any person lies in service to his fellow men and women. The big challenge to our civilisation is not Oz, a magazine I haven’t seen, let alone read. Nor is it permissiveness, although I agree our society is too permissive. Any society which, for example, permits over one million people to be unemployed is far too permissive for my liking. Nor is it moral laxity in the narrow sense that this word is generally employed – although in a sense here we come nearer to the problem. It does involve morality, ethics, and our concept of human values. The challenge we face is that of rooting out anything and everything that distorts and devalues human relations.

Let me give two examples from contemporary experience to illustrate the point.

Recently on television I saw an advert. The scene is a banquet. A gentleman is on his feet proposing a toast. His speech is full of phrases like “this full-bodied specimen”. Sitting beside him is a young, buxom woman. The image she projects is not pompous but foolish. She is visibly preening herself, believing that she is the object of the bloke’s eulogy. Then he concludes – “and now I give…”, then a brand name of what used to be described as Empire sherry. Then the laughter. Derisive and cruel laughter. The real point, of course, is this. In this charade, the viewers were obviously expected to identify not with the victim but with her tormentors.

The other illustration is the widespread, implicit acceptance of the concept and term “the rat race”. The picture it conjures up is one where we are scurrying around scrambling for position, trampling on others, back-stabbing, all in pursuit of personal success. Even genuinely intended, friendly advice can sometimes take the form of someone saying to you, “Listen, you look after number one.” Or as they say in London, “Bang the bell, Jack, I’m on the bus.”

To the students [of Glasgow University] I address this appeal. Reject these attitudes. Reject the values and false morality that underlie these attitudes. A rat race is for rats. We’re not rats. We’re human beings. Reject the insidious pressures in society that would blunt your critical faculties to all that is happening around you, that would caution silence in the face of injustice lest you jeopardise your chances of promotion and self-advancement. This is how it starts, and before you know where you are, you’re a fully paid-up member of the rat-pack. The price is too high. It entails the loss of your dignity and human spirit. Or as Christ put it, “What doth it profit a man if he gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his soul?”

Profit is the sole criterion used by the establishment to evaluate economic activity. From the rat race to lame ducks. The vocabulary in vogue is a give-away. It’s more reminiscent of a human menagerie than human society. The power structures that have inevitably emerged from this approach threaten and undermine our hard-won democratic rights. The whole process is towards the centralisation and concentration of power in fewer and fewer hands. The facts are there for all who want to see. Giant monopoly companies and consortia dominate almost every branch of our economy. The men who wield effective control within these giants exercise a power over their fellow men which is frightening and is a negation of democracy.

Government by the people for the people becomes meaningless unless it includes major economic decision-making by the people for the people. This is not simply an economic matter. In essence it is an ethical and moral question, for whoever takes the important economic decisions in society ipso facto determines the social priorities of that society.

From the Olympian heights of an executive suite, in an atmosphere where your success is judged by the extent to which you can maximise profits, the overwhelming tendency must be to see people as units of production, as indices in your accountants’ books. To appreciate fully the inhumanity of this situation, you have to see the hurt and despair in the eyes of a man suddenly told he is redundant, without provision made for suitable alternative employment, with the prospect in the West of Scotland, if he is in his late forties or fifties, of spending the rest of his life in the Labour Exchange. Someone, somewhere has decided he is unwanted, unneeded, and is to be thrown on the industrial scrap heap. From the very depth of my being, I challenge the right of any man or any group of men, in business or in government, to tell a fellow human being that he or she is expendable.

The concentration of power in the economic field is matched by the centralisation of decision-making in the political institutions of society. The power of Parliament has undoubtedly been eroded over past decades, with more and more authority being invested in the Executive. The power of local authorities has been and is being systematically undermined. The only justification I can see for local government is as a counter- balance to the centralised character of national government.

Local government is to be restructured. What an opportunity, one would think, for de-centralising as much power as possible back to the local communities. Instead, the proposals are for centralising local government. It’s once again a blue-print for bureaucracy, not democracy. If these proposals are implemented, in a few years when asked “Where do you come from?” I can reply: “The Western Region.” It even sounds like a hospital board.

It stretches from Oban to Girvan and eastwards to include most of the Glasgow conurbation. As in other matters, I must ask the politicians who favour these proposals – where and how in your calculations did you quantify the value of a community? Of community life? Of a sense of belonging? Of the feeling of identification? These are rhetorical questions. I know the answer. Such human considerations do not feature in their thought processes.

Everything that is proposed from the establishment seems almost calculated to minimise the role of the people, to miniaturise man. I can understand how attractive this prospect must be to those at the top. Those of us who refuse to be pawns in their power game can be picked up by their bureaucratic tweezers and dropped in a filing cabinet under “M” for malcontent or maladjusted. When you think of some of the high flats around us, it can hardly be an accident that they are as near as one could get to an architectural representation of a filing cabinet.

If modern technology requires greater and larger productive units, let’s make our wealth-producing resources and potential subject to public control and to social accountability. Let’s gear our society to social need, not personal greed. Given such creative re-orientation of society, there is no doubt in my mind that in a few years we could eradicate in our country the scourge of poverty, the underprivileged, slums, and insecurity.

Even this is not enough. To measure social progress purely by material advance is not enough. Our aim must be the enrichment of the whole quality of life. It requires a social and cultural, or if you wish, a spiritual transformation of our country. A necessary part of this must be the restructuring of the institutions of government and, where necessary, the evolution of additional structures so as to involve the people in the decision-making processes of our society. The so-called experts will tell you that this would be cumbersome or marginally inefficient. I am prepared to sacrifice a margin of efficiency for the value of the people’s participation. Anyway, in the longer term, I reject this argument.

To unleash the latent potential of our people requires that we give them responsibility. The untapped resources of the North Sea are as nothing compared to the untapped resources of our people. I am convinced that the great mass of our people go through life without even a glimmer of what they could have contributed to their fellow human beings. This is a personal tragedy. It’s a social crime. The flowering of each individual’s personality and talents is the pre-condition for everyone’s development.

In this context education has a vital role to play. If automation and technology is accompanied as it must be with a full employment, then the leisure time available to man will be enormously increased. If that is so, then our whole concept of education must change. The whole object must be to equip and educate people for life, not solely for work or a profession. The creative use of leisure, in communion with and in service to our fellow human beings, can and must become an important element in self-fulfilment.

Universities must be in the forefront of development, must meet social needs and not lag behind them. It is my earnest desire that this great University of Glasgow should be in the vanguard, initiating changes and setting the example for others to follow. Part of our educational process must be the involvement of all sections of the university on the governing bodies. The case for student representation is unanswerable. It is inevitable.

My conclusion is to re-affirm what I hope and certainly intend to be the spirit permeating this address. It’s an affirmation of faith in humanity. All that is good in man’s heritage involves recognition of our common humanity, an unashamed acknowledgement that man is good by nature. Burns expressed it in a poem that technically was not his best, yet captured the spirit. In “Why should we idly waste our prime…”:

“The golden age, we’ll then revive, each man shall be a brother,

In harmony we all shall live and till the earth together,

In virtue trained, enlightened youth shall move each fellow creature,

And time shall surely prove the truth that man is good by nature.”

It’s my belief that all the factors to make a practical reality of such a world are maturing now. I would like to think that our generation took mankind some way along the road towards this goal. It’s a goal worth fighting for.” – Jimmy Reid

Thankyou,Jacob

Yes, Jacob, thanks very much for posting Jimmy Reid’s speech.

I really enjoyed reading it. In Reid’s Scottish accent it must have been inspiring.

If the OWS movement had a Jimmy Reid their message would reverberate around the globe like a 2nd Krakotoa.

There spoke a very wise man….and that was 30 years before things became really bad and obvious.

Changing tack, my bugbear at the moment is business TV… CNBC, Bloomberg and the rest. It is just soft porn for gamblers. Might as well watch the horse racing. Now everyone had superanuation and 401ks with skin in the game, these shallow pratts get more credence and viewership than they deserve.

I’ve noticed the trend is more and more towards young “pretty” girls who blandly agree everything the greasy, bald headed experts proclaim (excepting Marshall A … Who they find hot btw). My biggest dislike is that gushing Australian neoliberal on BBC world. The guy makes me puke everytime he mentions Markets.

Good and useful comments …. thanks.

Ken, I here this too, I believe the point form MMT, I could definitely be wrong, is that government spending stimulates aggregate demand so that people can pay to watch his one man show. Furthermore, I think Professor Wray addressed your second point about not everyone can do it with his analogy on dogs in a back yard. Basically some more trained or qualified to do a certain job will find work but if 9 jobs exist for 10 people, no amount of hard work or training will provide 10 jobs.

Am I wrong? I am new to this.

“they’ll soon discover that in reality this type of small service sector they provide is dependant on huge industry (Which is always either directly or indirectly run by Government) which they satellite around.”

Take another example The evil one (Murdoch). Won’t find him being grateful to national socialist Germany and state owned NASA for developing the rockets and technology that gives him the monopolies in SATELLITE broadcasting.

The big, interfering government is just fine when it fully enables power and control to be shifted to unelected elites. A little thing we called fascism in the old fashioned world. Mussolini come back…all is forgiven. (Pardon me his spirit has already come back embodied in Carlo Monti… Fiat will be pleased, just like old times.)

World wide web….. Wouldn’t of happened without Government…. I could go on…

“Basically some more trained or qualified to do a certain job will find work but if 9 jobs exist for 10 people, no amount of hard work or training will provide 10 jobs.

Am I wrong? I am new to this.”

Your maths is just fine. 10 pairs of feet won’t fit into one pair of shoes.

The only way for the maths to work is if there are 9 lazy, profligate fools and 1 top talent that does all the work. Apparently this is what most people believe.

Dear Joey (at 2011/11/23 at 7:22)

Case study: the parable of 100 dogs and 95 bones

Imagine a small community comprising 100 dogs. Each morning they set off into the field to dig for bones. If there enough bones for all buried in the field then all the dogs would succeed in their search no matter how fast or dexterous they were.

Now imagine that one day the 100 dogs set off for the field as usual but this time they find there are only 95 bones buried.

Some dogs who were always very sharp dig up two bones as usual and others dig up the usual one bone. But, as a matter of accounting, at least 5 dogs will return home bone-less.

Now imagine that the government decides that this is unsustainable and decides that it is the skills and motivation of the bone-less dogs that is the problem. They are not skilled enough.

So a range of dog psychologists and dog-trainers are called into to work on the attitudes and skills of the bone-less dogs. The dogs undergo assessment and are assigned case managers. They are told that unless they train they will miss out on their nightly bowl of food that the government provides to them while bone-less. They feel despondent.

Anyway, after running and digging skills are imparted to the bone-less dogs things start to change. Each day as the 100 dogs go in search of 95 bones, we start to observe different dogs coming back bone-less. The bone-less queue seems to become shuffled by the training programs.

However, on any particular day, there are still 100 dogs running into the field and only 95 bones are buried there!

You can find pictorial version of the parable here (for international readers this version was very geared to labour market policy under the previous federal regime in Australia and was written around 2001).

In the US there are about 91 bones for every 100 dogs and in Spain 76 bones for every 100 dogs! The number of bones available in Europe and Britain are declining by the day.

The point is that fallacies of composition are rife in mainstream macroeconomics reasoning and have led to very poor policy decisions in the past.

As Bill pointed out in another blog. Neoliberalism diverts the focus to employability rather than employment.

Bill

When I looked at the chart which referances the income of family by % (table 3), it looks to me that the top .01 %, which is actually the top one in 10,000, made 24 million after tax. This is very different then the top one percent you are quoting in your blog, no?

Thank you for the continued outstanding analyses.

David Rojer, md

Entrepreneurship doesn’t depend on a small number of people having huge amounts of money. It depends on large numbers of people having enough extra money and leisure time to pursue their own ideas, without fear that doing so will impoverish them. It’s no surprise that there was actually more entrepreneurship at a time when the majority of Americans had more money, leisure time, and economic security than they do now.

How much productivity improvement since 1950 can be attributed to capital investment? And why should workers be rewarded for productivity increase that may be considered a result of the tools they were provided out of those capital investments?

Richard Gay: How much productivity improvement since 1950 can be attributed to capital investment??

Why start only 1950 a.d.? Lets start with 1950 b.c.!

Richard Gay, – based on personal experience I would say that in manufacturing at least 90% of productivity improvement in America and Europe was investment up to about 1990. Then TQM, JIT, lean manufacturing, zero defect, delayering and self managing teams took off, and for the next 15 years probably 50% was due to better mgmt practises. In other activities most gains were due to computerization of hitherto manual activities.

when economist use a common, everyday word like investment, it has a special meaning, and economists, a miniscule fraction of the population, expect everyone else to conform to the economist way of thinking.

I guess thats cause economists are so much smarter then everyone else, that it is ok, that the 299,995,000 people who are not economists take time out of their schedules to learn what the 5,000 economists have to say

(taking the us population, to 1st order, ad 300e6; now that I think about it, it should probably be something ike 200,995,000 adults and 5,000 economists)

Dear Ezra Abrams (at 2011/12/30 at 10:50)

Your point is unclear.

I realise that the use of the term “investment” is varied across the population. That is why when I use the term “investment” I have to clarify that I am using it in my guise as a professional economist to make sure the meaning of my writing is clear.

Nothing more than that.

When in Spain – it is better to speak Spanish.

best wishes

bill