It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Some notes on Aggregate Supply Part 2

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text by the end of this year. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

Continuing the discussion in Chapter 9 An Introduction to Aggregate Supply

A basic insight in macroeconomics is that one person’s spending is another person’s income. We might also say that for every dollar spent by a purchaser, the income of the seller goes up by the same amount. As we saw in Chapter 5 National Income and Production Accounts, the total value of all goods and services produced each period (say a year) is exactly equal to the national income received by all recipients over the same period.

In understanding aggregate supply, we begin with a single firm. Each firm purchases inputs (raw materials, labour etc) in the hope of transforming these inputs into goods and services (intermediate and/or final) which can be sold for money.

Applying the spending equals income accounting rule, we know that the total revenue for a firm (its sales) equals the sum of its total costs and its realised profits in each period. Profits are simply the excess of sales revenue over total costs. Realised profits in a capitalist system are a residual that are observed after production and sales have taken place. The firm expects to make a profit but may underestimate costs or overestimate total revenue and end up making a loss.

As an example, assume that a firm generates sales revenue equal to $20 million in the current year. To achieve this revenue it has to incur costs in the form of wages and salaries, costs of raw material bought and used in production, costs associated with its plant and equipment (for example, rents, interest payments on loans) and other operational costs.

The costs of production are itemised as follows:

| Wages and salaries | $12 million |

| Raw materials | $4million |

| Plant and Equipment costs (rent, interest etc) | $2 million |

| Other costs | $1 million |

| Total costs of production | $19 million |

From this example, we calculate that the firm received profits of $1 million. We have abstracted from taxes and depreciation here to avoid getting into discussions about the difference in the National Accounts between National Income and Gross National Product which we explained in Chapter 5 (see also Footnote 1, page 252 Tarshis, 1947 for an explanation).

All the costs of productions are paid to workers, suppliers of raw materials, property owners, banks who provide finance and the like. For those recipients the costs of production for the firm are income flows.

Clearly, these accounts are found in all the firms producing goods and services in the economy. The firms in the economy are also interlinked because one firm may purchase raw materials or plant and machinery etc from other firms. So some of the costs of production for the firm depicted in the table above will be the sales revenue of other firms.

So for each firm’s revenue we can track the flow of spending by that firm throughout the economy to satisfy ourselves that total spending equals total national income.

In the 1947 textbook – The Elements of Economics – by Lorie Tarshis we read (page 254):

… a firm’s sale receipts in any period are equal to the sum of its costs and profits for that period. All items of cost can be identified with someone’s income: wage and salary costs directly; and costs for raw materials after one or several steps in the analysis of the activities of firms that supply raw materials to our firm, or to the supplying firm, and so on. Likewise, the profits earned are, of course, the income of the firm’s owners. Hence a firm’s sale receipts in any period equal the incomes earned in producing what it sold.

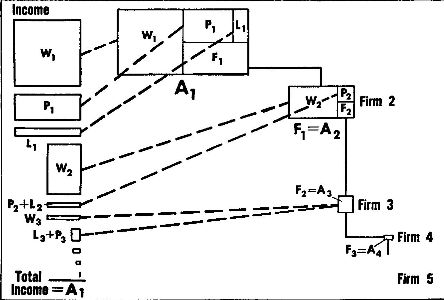

He produced this diagram (his Figure 57, page 254) to represent the relationship between sales revenue at the firm level and national income at the macroeconomic level.

Figure 9.3 Firm sales and national income

[Reference: Tarshis, L. (1947) The Elements of Economics, Houghton and Mifflin, Boston]

Block A1 is the total revenue for Firm 1 in the current period. It uses that revenue to pay wages and salaries (W1), rent and interest (L1), and raw materials purchased from other supplying firms (F1).

The profits for Firm 1 (P1) = A1 – [W1 + L1 – F1]

Total income generated by Firm 1 = (P1) + W1 + L1 + F1 = A1

Assuming Firm 2 is the only one raw material suppier to Firm 1, then its total revenue (A2) is equal to F1), the purchases of raw materials by Firm 1.

Firm 2 also incurs costs in generating the revenue (W2), L2), F2)) and generates profits P2).

Total income generated by Firm 2 = (P2) + W2 + L2 – F2 = A2

The diagram shows that F2 is the revenue of Firm 3 (A3), which is similarly distributed to providers of inputs.

The logic is to note that F1 = A2 and F2 = A3 and so on until all the inter-firm transactions are exhausted. We are abstracting here from other inputs that firms might supply each other.

Using that logic we can see that total revenue generated in the economy (sales or spending) is equal to total incomes produced. Total incomes are the sum of profits and other incomes.

In Chapter 5, we were warned to be careful to avoid double counting when assessing the national income in any period.

[NOTE: Reiteration of Double Counting here]

Price Determination

Clearly, firms seek to generate a profit over and above the costs of production. How does it go about setting the price that it will accept for its output?

Firms are assumed to operate in a non-competitive economy. You may have considered the case of perfect competition in a microeconomics course where firms are assumed to have no price setting discretion because the market is so large and firms are assumed to be so small.

We are thus introducing oligopoly as a basic assumption rather than the mainstream use of perfect competition. Firms are this considered to be price-setters rather than price-takers. Firms are assumed to fix their prices as a mark-up over costs. Economists are divided about the determinants of the mark-up and the costs considered relevant in the pricing decision by firms.

Further, debate remains as to whether the mark-up is invariant to the state of demand. However, the use of the mark-up as a basic description of firm behaviour in the real work is difficult to dispute.

In the real world, firms typically have discretionary price-setting power and seek a rate of return on the capital employed, which necessitates that they generate a profit margin over total costs of production.

The total price per unit sold must therefore cover its unit costs of production plus the profit margin. How we account for overhead and other fixed costs costs is debatable. They may be included in unit costs or, alternatively, the profit margin may be considered to be a gross amount which includes overheads and other fixed costs plus net profits per unit.

Firms are thus assumed to employ a mark-up pricing model such that:

(9.2) P = (1 + m)[W/LP]

where P is the price of output, m is the per unit mark-up on unit labour costs, W is the money wage and LP is the measure of labour productivity. The variable LP is defined as the units of output per unit of labour input.

If LP = 0.5 then the average product of labour is such that 2 labour hours are required to produce one unit of output. If the money wage (W) was $5 per hour, then the unit labour costs (cost of a unit of output) would be $10.

The mark-up (m) is set to provide a surplus above the direct unit labour costs to account for fixed (overhead) labour and other costs in addition to ta provision for profits (return on equity). The amount of profit desired is related, in part, to the amount of investment that the firms plan to undetake because retained earnings are an important source of internal finance that the firm taps to reduce its exposure to higher costs of external funding of projects.

In the short-run, the price will be rigid with the firm supplying output according to demand. Prices changes would occur when there were changes in the money wage rate or other variable costs, the mark-up (margin), or trend labour productivity. Trend labour productivity is used here to differentiate it from the cyclical swings that occur in labour productivity, which we consider in Section 9.X of this Chapter.

The mark-up (m) is a reflection of the market power of the firm. The higher the market power, the higher will be the margin. In more competitive sectors, the margin will be lower than less competitive sectors. Changes in competitiveness in a sector will, over time, lead to changes in the size of the mark-up.

If in our example, the mark-up (m) is set at 40 per cent, then the firms will price its output at $14 per unit ($10 by 1.40).

[NOTE – A SECTION ON AGGREGATION TO GO FROM FIRM MARK-UP TO ECONOMY-WIDE PRICE RULE]

The features of this approach are as follows. First, prices are unambiguously a function of costs.

Second, firms use their price-setting discretion to generate a monetary surplus above average direct costs. This monetary surplus is designed to cover profits. Importantly, profits are considered to be influenced in the short-run by the ability of firms to realise the mark-up on unit costs. Factors which may squeeze the mark-up will accordingly also squeeze profits.

Third, the mark-up impacts directly on the real wage that the workers receive. If total marked-up costs only embrace (for simplicity) wage costs then total wage costs are the product of the money wage rate W times the number of workers employed N. That is, total wage costs = WN.

A simplified price mark-up model would be in this case:

(9.2b) P = (1 + m)WN/Y

where all the terms are as defined previously.

We can re-write this equation as:

(9.2c) Y/(1 + m) = WN/P

and further re-arrange it to get:

(9.2d) W/P = (Y/N)/(1 + m)

which says that the real wage (W/P) is dependent on the average productivity of labour (Y/N) and the size of the mark-up. The larger the mark-up (m), other things being equal, the lower is the real wage.

Fourth, the volume of profits (as distinct from the per unit profit) is dependent on the size of the mark-up – which influences the per unit profit – and the volume of output sold in any one period. The latter is determined by the state of aggregate demand in the economy and as we saw in Chapters 7 and 8, is determined by the level of household consumption expenditure, private investment expenditure, net exports and government spending.

Firms plan to increase profits by raising the mark-up. They might also plan to raise investment spending if they are to realise the extra profits especially since the implied real wage squeeze is likely to have detrimental effects on disposable income received by households and hence consumption expenditure. In Chapter 12, we consider investment behaviour and introduce the famous Kalecki Profits Equation, which shows that firms generate profits according to what they spend.

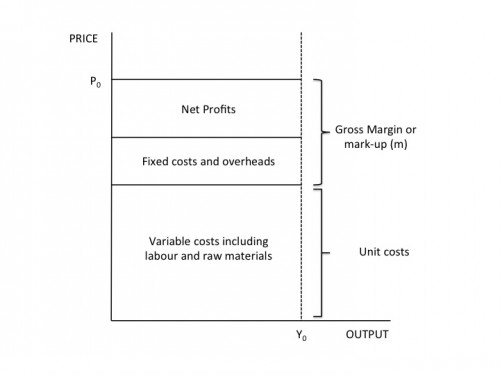

Figure 9.4 shows the way in which the price set by all firms (P0) at some point in time is distributed as incomes. Here the current level of output being produced is Y0. The price P0 is a markup on total unit costs allowing for fixed costs and overheads and a net profit margin.

Total revenue for the economy as a whole is the area defined by P0 times Y0 and the distribution of that level of output as income is shown by the areas below the price line.

Firm thus supply the output that is demanded at the price P0. They produce a given level of output according to their expectation of total spending in the economy. The diagram below makes no presumption that the level of output Y0 is consistent with that expectation. It is, in fact, total output sold and may or may not satisfy the firms’ expectations.

In that sense, the net profits generated may be below or above the level that the firm aimed to achieve at the beginning of the production period.

Figure 9.4 Output, sales and national income (click for larger image)

Fifth, usually mark-up theories assume that the immediate impact of changes in demand on the mark-up and hence prices is small. For the planning period ahead, firms calculate their costs and desired profits on the basis of an expected level of output which they believe they can sell. Deviations in this expected level of demand promote output changes rather than price changes.

The General Aggregate Supply Function

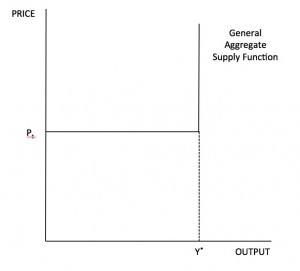

Before we consider these complicating factors – changes in productivity, changes in competitiveness – it is useful to consider what the price determination rule means for the shape of the aggregate supply function.

If we assume that m, W and LP are constant in the short-run then the aggregate supply curve would be a horizontal line in the price-real income graph up to some full capacity utilisation point (Y*). Economists sometimes refer to a horizontal line in this context as being perfectly elastic. Firms in aggregate will supply as much real output (goods and services) as is demanded at the current price level set according to the mark-up rule described above.

Figure 9.5 is similar to Figure 9.4 but adds the full capacity utilisation level of real output (Y*) to derive the General Aggregate Supply Function (AS). This shaped AS function is sometimes referred to as a reverse-L shape for obvious reasons.

The horizontal segment has been explained by the price mark-up rule and the assumption of constant unit costs. But why does it become vertical after full employment?

After this point, the economy exhausts its capacity to expand short-run output due to shortages of labour and capital equipment. At that point, firms will be trying to outbid each other for the already fully employed labour resources and in doing so would drive money wages up. We will return to this possibility later in this Chapter.

Under normal circumstances, the economy will rarely approach the output level (Y*, which means that for normally encountered utilisation rates the economy faces constant costs.

There is some debate about when the rising costs might be encountered given that all firms are unlikely to hit full capacity simultaneously. The reverse-L shape simplifies the analysis somewhat by assuming that the capacity constraint is reached by all firms at the same time. In reality, bottlenecks in production are likely to occur in some sectors before others and so cost pressures will begin to mount before the overall full capacity output is reached.

This could be captured in Figure 9.5 by some curvature near Y*, thus eliminating the right-angle. We consider this issue in more detail in Chapter 11 Inflation and Unemployment.

Figure 9.5 The General Aggregate Supply Function (AS) (click for larger image)

Some Properties of the General Aggregate Supply Function (AS)

The AS equation is simply the price determination model equation (9.2), which shows that in the short-run, the behaviour of the aggregate supply in the economy depends on m, W and LP.

Accordingly:

- If the money wage rate rises, other things equal, the unit cost level rises and the firms would translate this into a price rise via the constant mark-up.

- If there is growth in labour productivity (LP) as a result of say, increased labour force morale, increased skill levels, more technologically-based production techniques, better management, and the like, then unit costs (W/LP) will fall. This means that the firms can generate the same profit margin at lower prices. The AS function would thus shift downwards by the extent of the decline in unit costs.

- Variations in the mark-up (m) will cause the price level to change. Increases in industrial concentration, more advertising etc may lead to firms being able to increase the overall profit margin that can be sustained. Tight conditions in the goods and services market, where sales are constrained, may lead firms to reduce the mark-up desired as they all struggle for market share. This could occur as a result of flagging sales and strong trade unions pushing (successfully) for wage increases. Thus to avoid losing market share, the firms may choose to absorb some of the cost rises into the margin.

- If employment is below full employment and thus Yactual < Y*, which means there is an output gap present, then increases in aggregate demand (spending) which are seen by firms to be permanent will result in an expansion of output without any price increases occurring. If the firms are unsure of the durability of the demand expansion they may resist hiring new workers and utilise increased overtime instead. That is, they initially respond to the increased aggregate spending by increasing hours of work rather than persons employed. The higher costs (as labour productivity falls) are likely to be absorbed in the profit margin because firms desire to maintain their market share overall.

[NOTE: There is a section here on labour productivity – technology – costs of production]

The Mark-up, the Real Wage, Conflict and Inflation

[NOTE: This section may move to Chapter 11 Unemployment and Inflation]

The General Aggregate Supply Function provides a framework for examining the incidence of inflation and is based on three broad features:

- The goods and services market is assumed to be non-competitive (oligipolistic). This means that in most industries a few firms dominate price setting. Smaller firms are forced to price accordingly or lose access to the market.

- The labour market is characterised by wage setting processes that depend on bargaining between workers and firms, sometimes directly and other times via specific wage setting institutions.

- Firms access credit through the banking system to finance enterprise commitments in advance of sale. Changes in the broad money supply (to be considered in detail in Chapter 14 Money and Banking) arise from the demand by firms for credit.

The introduction of oligopoly as a basic starting point for the analysis, rather than the mainstream use of perfect competition, allows us to focus on inflation as the outcome of conflict over the distribution of income between competing groups in the economy (wage earners and profit receivers).

Four main groups in the economy that have a stake in the income which the economy produces in the current period can be identified:

1. Workers struggle to increase their command over real goods and services via their real wages.

2. Firms seek to expand their profits.

3. Suppliers in the Traded-goods sector gain revenue by providing inputs.

4. The government sector seeks to tax the non-government sector to create space for its own expenditure plans.

These competing claims are expressed in nominal terms. That is, a monetary claim on total income.

These nominal claims for the available real income that the economy produces are clearly in conflict with each other. There is no reason why the sum of the competing nominal claims should be exactly equal to the level of real output produced in any period.

Workers may try to raise their real wage by pushing for higher money wages, which may be frustrated by price rises as firms react to protect their profit margin. Firms may be the aggressors by increasing the mark-up which then elicits what we call real wage resistance – workers try to increase money wages because they resent their real wage being cut. This wage-price (or price-wage) struggle has the potential to generate inflation if left unchecked.

Various methods can be used by the different groups to reconcile the nominal claims on real output if they are mutually incompatible.

Two important sources of resolution in the real world are relevant:

- Changes in the level of aggregate demand and output may be used to resolve the conflict. The volume of profits depends, in part, on the level of demand as does the size of the mark-up. A recession, induced by contractionary fiscal and/or monetary policy can squeeze profits by reducing the ability of the firms to pass on (that is, realise) costs. A recession also raises the level of unemployment and may quieten the aspirations of the worker for higher real wages (that is, quell any real wage resistance) as workers begin to fear loss of employment.

- The government, fearing the political consequences of a policy-induced recession, may try to introduce an incomes policy to break into the competition between workers and firms for increased real income.

Inflation pre-dates these reconciliation attempts. Thus inflation is seen as the outcome of one or more groups in the economy attempting to expand their own share of national income. With a given national income, one group can only achieve an increase in its share if another group is willing to reduce their share.

That is, one group’s gain is another group’s loss. Each group has at its disposal the means to protect its own share, although the ability to enforce these means varies according to the state of the economy, among other things.

The obvious response by a threatened group is to raise its own price (money wage, product price, raw material supply price, or tax rate) to compensate for the loss of real income. Inflation will continue until a resolution to the conflict is found.

Typically, this outbreak in prices is complicated by the development of inflationary expectations among the competing groups. As inflation increases the various groups plan price rises in advance to cope with the expected reactions of the other competing groups. The continuation of inflation presupposes that each group strives and is able to pass on the loss in its real income onto another group or groups. Ultimately, this implies that the money supply must increase unless all the price rises are absorbed via increases in the velocity of broad money. We consider these issues in Chapters 11 and 14.

However, this is where the existence of credit money is relevant. The money supply is endogenous and highly responsive to the demand for credit by the non-government sector. The question of finance is important because production involves the commitment of resources by firms which must be paid for in advance of the realisation of revenue, via the sales of output.

Increases in planned expenditure by firms may arises from plans by firms to expand output to increase their market share or from the fact that input prices have risen. In either case, the firms increase borrowing from the banks (assuming credit-worthiness) and the money supply increases.

The increasing money supply is the obvious way that the inflation process can gain momentum. At the firm level, if the firm can gain loans to finance higher input prices, which it then passes on to final consumers and pays for the loans by raising its prices, then inflation can take hold.

If the firm was not able to gain this increased finance on satisfactory terms from the bank and therefore the money supply would not validate the initial push for higher prices, then it would have to employ some combination of reduced input purchase and/or lower prices for its output.

Conclusion

More next Friday. We will consider the factors that influence the growth of aggregate output per hour (that is, labour productivity measured in hours), an extension of the simple aggregate supply model to embrace employment and wage determination, the implications of this extension for real wage movements, and a brief excursion in to the main alternatives – the Classical and Keynesian models.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Regarding:

“The government sector seeks to tax the non-government sector to create space for its own expenditure plans”

as a

“stake in the income which the economy produces in the current period”…

“Create space” – this strikes me as awkward, as if the point is too subtle to really explain in this context. But it still conveys the idea that taxes are the government’s “share” of current income, and suggests that the government’s motive in taxing is to fund its ability to spend. I think this should be more fully explained.

Cheers

In other contexts, I would have expected “creates space” to read something like ” to drain demand from the private sector, thus ensuring that the government’s spending is not inflationary…”

It may be useful to include a paragraph about stock valuation when determing profits.

Valuing a physical stock count at the lower of cost and net realisable value is the biggest issue

when it comes to determining profits in a period because the calculation is often very subjective and has a direct impact on the bottom line.

It does not affect the overall thrust of the subsequent discussion but may give it more street cred

What is the planned ETA for this text ? I recall mention of this text or perhaps I didn’t around 2002/3.

There is a sign error in the equation:

“Total income generated by Firm 1 = (P1) + W1 + L1 – F1 = A1”.

It should be +F1. It’s worthwhile saying explicitly, as Tarshis does, that the total income is A1 and you get this result from the sequence of equations:

A1 = P1 + W1 + L1 + F1 = P1 + W1 + L1 + A2

= P1 + W1 + L1

+ P2 + W2 + L2 + A3

etc, until you run out of firms so that you finish up with the total income as

A = A1 = P + W + L = (P1 + P2 + P3 + P4+ … ) + (W1 + W2 + W3 + … ) + (L1 + L2 + L3). Then, of course, A1 is the total income in this example because firm 1 does not sell to other firms and the other firms only sell to other the other firms in the chain. Hence the need to be careful about double counting.

Dear Alan Dunn (at 2012/07/14 at 17:32)

The text will be finished by early 2013. The book you might have heard about in 2002/03 was not this text.

best wishes

bill

Dear Tony (at 2012/07/14 at 18:38)

Thanks for the correction of the typographical error.

best wishes

bill

just read this after reading neo liberals on bikes(funny and pertinent)

on this blog we read about price being cost +mark up

on the other the govts not being financially constrained making greens neo liberalism misplaced

and then the general discussion about the real limits of govt spending -inflation

and the JG employment buffer

my question linking the two blogs

if government spending brings down costs does that not change the dynamic of the limits of govt spending?

so why not a universal benefit replacing welfare and pension giving the ability for rational life /work decisions

coupled with deflationary policies which bring down costs and facilitate labour productivity

spending on much needed energy production for instance subsidizing costs for households and employers alike

hopefully production with a smaller carbon foot print green as well

subsidizing mass transportation costs food costs communication costs

and for that other vital cost we would not need to spend at all- rents- just rent controls and mortgage controls

if this was coupled with a substantial universal credit” when everyone is a freeloader no one is a free loader”

inflation would be offset and some may chose less hours which along with increasing demand should provide everyone with the opportunity to work if that if that is what they chose

re: “If the firm was not able to gain this increased finance on satisfactory terms from the bank and therefore the money supply would not validate the initial push for higher prices, then it would have to employ some combination of reduced input purchase and/or lower prices for its output.”

without an increase in the working capital line of credit, the firm can reduce its output in the face of increased unit costs. It’s not clear to me that it is obliged to lower the price it seeks for its output. Are you saying that it would seek to increase market share at a lower price to increase the velocity of its turnover?