It’s Wednesday and I just finished a ‘Conversation’ with the Economics Society of Australia, where I talked about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to current policy issues. Some of the questions were excellent and challenging to answer, which is the best way. You can view an edited version of the discussion below and…

Productivity and the response of firms to the business cycle

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text by the end of this year. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

The following text continues Chapter 9 Introduction to Aggregate Supply. The numbering of Sections and Sub-Headings will be consistent once the text is in draft form.

Factors Affecting Aggregate Output per Hour

What factors determine the impact of change in hours of employment on aggregate output? Over time, many influences are at work. Such things as, improving technology, changes in the average quality of labour from increased education and health, changes in organisational and management skills, will steadily allow more output to be produced from a given quantity of inputs.

In seeking to understand short-run employment and output determination, we adopt the view that these influences work slowly over time and so we abstract from them in our short-run analysis.

The neo-classical production function analysis, which is standard in most textbooks, assumes that in the short-run, will all other productive inputs (capital, land etc) fixed, output will increase at a decreasing rate as more hours of employment are used by firms.

This is the so-called Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity and allows economists of this persuasion to postulate an increasing marginal cost relationship with respect to output (costs increase at an increasing rate as more output is produced). In turn, this leads to a decreasing labour demand function with respect to the real wage. These relationships are derived from the assumption that firms produce and employ such that their profits are maximised at given price and real wage rates.

The validity of “the Law” has been the subject of considerable controversy. In essence it is a theoretical construct – an unproven assertion. No conclusive empirical evidence has ever been assembled to substantiate the “the Law” as a reasonable generalisation of production relationships in modern monetary economies.

On the contrary, there is a mass of empirical evidence available, derived from actual studies of business firms. to support the view that costs of production are constant in the relevant or normal range of output and that the Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity is not applicable.

In fact, a strong positive relation between output per hour and the business cycle is observed in the real world. We call this a pro-cyclical movememnt in output per hour, which means that output per unit of labour input increases as the level of production and employment increases.

The pro-cyclical pattern of labor productivity (output per hour) means that costs per unit of output will not increase as output increases. Total costs will obviously rise but the per unit costs will decline as the economy approaches full capacity.

If W is the money wage rate and N is total employment measured in hours, then total labour costs in any period are:

(9.1) C = W.N

If Y is real output, then unit labour costs (ULC) are the cost incurred for each extra unit of output, which is given as:

(9.2) ULC = W.N/Y

Noting that (Y/N) is output per unit of input (or labour productivity), we can re-arrange Equation (9.3) as:

(9.3) ULC = W/(Y/N)

In other words, all the result that depend on the operation of the Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity are no longer valid approximations of the way the economy works. In particular, the shape of the aggregate supply curve and the labour demand curve at both the firm and aggregate level will not bear neo-classical proportions.

This shows that if the money wage rate is fixed then the change in ULC will be driven by changes in labour productivity. If output per hour rises as economic output increases then unit labour costs fall as the economy approaches its peak.

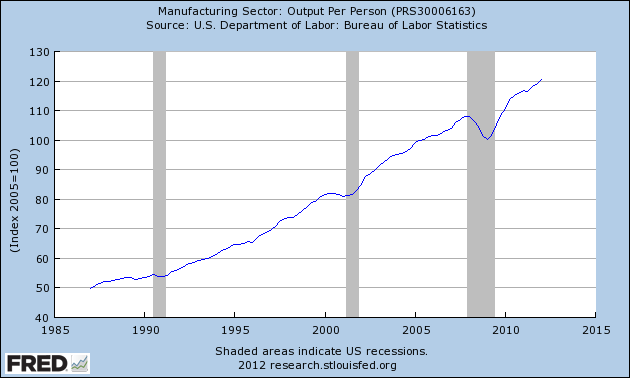

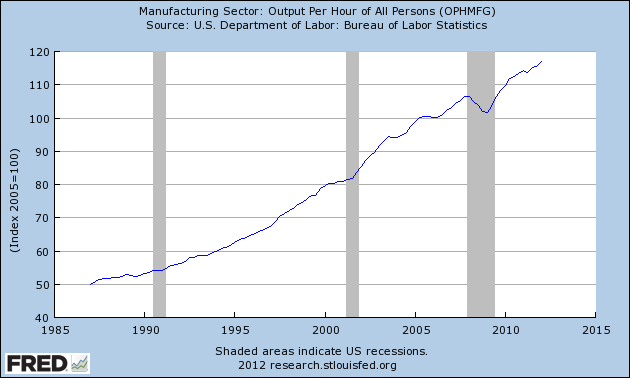

Consider Figures 9.Xa and Figure 9.Xb, which show real output per person and real output per hour in the US manufacturing sector, respectively. The shaded areas are the NBER recessions.

Both measures of labour productivity are pro-cyclical. During a recession, when output is falling, productivity falls. This is is contradistinction to the Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity.

The US manufacturing sector behaves in a similar way with respect to pro-cyclical movements in labour productivity to all advanced economies.

advanced economies.

[Note: the Figures will be reconstructed in the final text from our own database and conform to the style of the textbook]

FIGURE 9.Xa US Manufacturing Output Per Person Employed

Source: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/OPHMFG?cid=32349

Figure 9.Xb US Manufacturing Output Per Hour of All Persons

Source: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/OPHMFG?cid=32349

The theory of production we present here is based on several stylised facts from the real world:

1. Economies are rarely at full employment and the existing capital stock is rarely fully utilised. Idle machines typically accompany idle workers when the economy goes into a downturn.

2. The capacity of firms to substitute one input (say, labour) for another (say, capital) in the production process is limited. In the real world, a typical firms employs a number of machines and types of equipment, which have more or less fixed labour requirements.

For example, say a firm provides services from an office and each worker requires a desk, a chair and a computer to perform their duties. In the usual course of events (barring putting on an extra shift) the firm has to increase its capital and labour in the proportions defined by the technology being used to expand output.

It doesn’t violate reality too much to simplify this stylised fact by assuming what economists refer to as fixed input coefficients technology.

Take a trivial example of a cleaning firm which uses brooms as its principle technology. It services a contract to sweep rooms in office blocks each day. It is hard to imagine two workers pushing one broom of one worker pushing two brooms. So to start production, the firms needs to combine its productive inputs in a fixed ratio (in this case, 1).

If the firm gained contracts for more office cleaning which exceeded the capacity of one cleaner then it would have to (given the technology being used) add another broom for the second worker to use and so on. So the productive inputs are added in fixed proportions defined by the technology being used.

What will the level of employment in this firm depend upon?

The firm will hire according to the demand for its services and its demand for labour will not be very sensitive to wage changes. Clearly, it will make decisions about viability of its operation based, in part, on wage costs. But on a day-to-day basis, if it is profitable at the current wage rates, then it will increase or decrease its demand for labour based on the revenue it can anticipate from sales.

In other words, effective demand drives labour demand.

Cutting wages would only redistribute total revenue towards profits, which might damage aggregate demand as workers will have less income to spend.

The neo-classical production theory, based on the Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity, considers that firms are able to substitute labour and capital freely and if the price of labour increases in real terms, the firms will quickly use less labour and more capital.

The problem with this conception is that firms are rarely able to substitute inputs quickly and to use more capital and less labour typically requires a total change in technology. Real wage movements would have to be very large to justify the firm scrapping their existing technology.

While the fixed input ratio assumption is extreme and shows the essential relationship between effective demand and employment, it doesn’t alter the story if we consider the more realistic case of limited substitution possibilities.

Consider how firms might act. Based on the current costs pertaining to capital and labour and the available technology, a typical firm will select the capital stock necessary to produce expected output. In making that decision, they are also committing to a certain labour demand given the relationship between the technology being used and the input proportions required.

Given the relative costs of labour and capital, a firm will reasonably chose the lowest cost technology it can afford. In turn, this will set the capital-labour input ratio that it will be more or less bound by in the coming production period.

The theory of production we present here is based on several stylised facts from the real world:

1. Economies are rarely at full employment and the existing capital stock is rarely fully utilised. Idle machines typically accompany idle workers when the economy goes into a downturn.

2. The capacity of firms to substitute one input (say, labour) for another (say, capital) in the production process is limited. In the real world, a typical firms employs a number of machines and types of equipment, which have more or less fixed labour requirements.

For example, say a firm provides services from an office and each worker requires a desk, a chair and a computer to perform their duties. In the usual course of events (barring putting on an extra shift) the firm has to increase its capital and labour in the proportions defined by the technology being used to expand output.

It doesn’t violate reality too much to simplify this stylised fact by assuming what economists refer to as fixed input coefficients technology.

Take a trivial example of a cleaning firm which uses brooms as its principle technology. It services a contract to sweep rooms in office blocks each day. It is hard to imagine two workers pushing one broom of one worker pushing two brooms. So to start production, the firms needs to combine its productive inputs in a fixed ratio (in this case, 1).

If the firm gained contracts for more office cleaning which exceeded the capacity of one cleaner then it would have to (given the technology being used) add another broom for the second worker to use and so on. So the productive inputs are added in fixed proportions defined by the technology being used.

What will the level of employment in this firm depend upon?

The firm will hire according to the demand for its services and its demand for labour will not be very sensitive to wage changes. Clearly, it will make decisions about viability of its operation based, in part, on wage costs. But on a day-to-day basis, if it is profitable at the current wage rates, then it will increase or decrease its demand for labour based on the revenue it can anticipate from sales.

In other words, effective demand drives labour demand.

Cutting wages would only redistribute total revenue towards profits, which might damage aggregate demand as workers will have less income to spend.

The neo-classical production theory, based on the Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity, considers that firms are able to substitute labour and capital freely and if the price of labour increases in real terms, the firms will quickly use less labour and more capital.

The problem with this conception is that firms are rarely able to substitute inputs quickly and to use more capital and less labour typically requires a total change in technology. Real wage movements would have to be very large to justify the firm scrapping their existing technology.

While the fixed input ratio assumption is extreme and shows the essential relationship between effective demand and employment, it doesn’t alter the story if we consider the more realistic case of limited substitution possibilities.

Consider how firms might act. Based on the current costs pertaining to capital and labour and the available technology, a typical firm will select the capital stock necessary to produce expected output. In making that decision, they are also committing to a certain labour demand given the relationship between the technology being used and the input proportions required.

Given the relative costs of labour and capital, a firm will reasonably chose the lowest cost technology it can afford. In turn, this will set the capital-labour input ratio that it will be more or less bound by in the coming production period.

Is the capital-labour ratio easily changed?

As a result of capital being specifically embodied in the form of machines, equipment, buildings and the like – once installed there is very little substitution possible.

The firm knows that if it needs to produce more output to meet the market demand then it will have to increase its demand for more labour and capital, in the proportions governed by the technology in use.

Add more labour alone will not increase output just as adding more capital alone will not increase output.

How does this affect our understanding of production costs?

In this economy, firms will adjust their input use to meet the fluctuations in demand for output. If orders decline, then their demand for inputs will decline. Both capacity utilisation and labour utilisation will decline.

But for the firm, capital becomes what economists call a free good. Relative to its purchase and installation costs the variable costs of running the capital are usually low. Economists call the major costs involved sunk, which means that the firm has already incurred them whether they run the plant or not.

Accordingly, the firm will use as much capital as is required to produce the current output that is being demanded. When demand falls, the firms simply leave some proportion of their capital stock idle.

But in doing so, they shed labour because the variable costs of the labour input are relatively high when compared to the fixed hiring and related costs.

What role does the real wage play in this? Even if the real wage fell to zero the firms would not employ more workers if aggregate demand didn’t justify it. Firms will not produce if there is not a prospect of sale (barring the small proportion of production they keep as inventories to smooth our orders).

How would a firm react to an increase in aggregate demand?

If there has been a prolonged downturn then we would observe idle capital and labour (unemployment). The unemployed workers are willing to work at the current wage rates but there is no demand for their services because effective demand is too low.

While we have reason to believe that unit costs decline as capacity utilisation increases, fixed factor input proportions mean that firms face constant unit costs in normal ranges of production. That is, we are assuming that money wages are fixed in the short-run and labour productivity is constant.

If the firms received increased orders for its output then it will seek to maintain its market share by increasing output. Assuming constant unit costs the firm will bring its idle capital back into production and hire more workers.

There would be no price pressures likely because there would be no pressure on costs. As output rises, the demand for labour increases at a constant real wage.

This suggests that the Aggregate Supply curve is very flat over the normal range of output. Increases in nominal demand will be met by increases in real output (income).

There are several reasons why firms might be reluctant to increase prices (even though costs might rise temporarily as we explain below) or reduce them when aggregate demand falls.

First, industries are characterised by a few dominant firms that exercise market power.

Second, consumer loyalty to products of other firms means that they will not react to a price fall in other similar products.

Third, there are significant costs involved in adjusting prices. Firms have to produce new price tags and catalogues.

What factors might explain the observed pro-cyclical movement in labour productivity?

The following factors help to explain the observed pro-cyclical pattern of labour productivity.

First, a dimension of the aggregation problem appears when we consider that the value of output per hour of employment varies considerably among the range of firms and industries that comprise the total economy.

For example, the manufacture of high-tech electrical goods would have a much greater output per hour of labour input than say the provision of hairdressing services.

It can be shown that even if diminishing returns were operating at the individual firm level (as assumption not a fact) suh a constraint need not be functional at the aggregate level.

If the proportions of output attributable to individual industries change as output increases (a fact observed in the real world), and the changes are such that the industries where diminishing returns are most apparent lose a disproportionate amount of their share in total output then labour productivity can increase. This hypothetical example merely indicates the dangers that are involved in adding up a set of non-linear relations operating at the micro level. It is beyond the level of understanding that is required to master the material in this textbook.

Second, and less esoteric, as far as the individual firm is concerned, the actual real world relationship between changes in labour hours and changes in output may not exhibit diminishing returns because other productive inputs may vary in the same proportion as the labour input.

Thus the neo-classical assertion that capita, in the from of specific plant and equipment, is always held constant confuses the distinction between the stock of capital in value terms – that is, its monetary worth and the flow of services that the stock produces which is revealed by the rate of capacity utilisation.

While the stock of capital changes only slowly over time, utilisation rates can vary in the short-run. Firms will leave machines idel as their production pans are changed in the face of declining demand for their products.

Unused machines and idle factory space is unlikely to raise the productivity of the remaining machines and equipment in use.

As production is increased when the firm believes that it can sell more output, unused machines are turned back on and unemployed workers are assigned to them. There is no reason to assume that output per unit of labour input on these machines would be any different to that derived from the plant that was kept active during the downturn.

Third, and of great practical importance is the observation that most firms desire to maintain long-term relations with their labour forces. The reason for this behaviour by firms relates to the fixed costs of hiring (recruiting, training and redundancy provisions) and to the need to maintain morale among the workers.

Efficiency is crucially dependent on the feelings that the workers have towards security and the like. Firms are also reluctant to dismiss specialised workers for fear of losing them permanently.

As a consequence, employment tends to fluctuate less violently that output or production. Labour productivity therefore falls in a recession and rises in booms.

In booms, output grows quickly, but the firm which has hoarded labour in the recession, does not immediately expand employment. It merely works its existing labour force more intensively – that is, adjusts hours of work rather than persons employed.

These adjustments are reinforced by the fact that hiring and firing decisions depend on future or expected sales. Firms will increase employment of new workers and incur the fixed costs if it expects to maintain a higher sales level.

If the rise in demand is not expected to be permanent (or the firms is not sure of its durability) then it will use overtime as the cheapest adjustment.

So in the short-run, costs might rises as overtime premiums are paid as the firm decides whether the increase in demand is permanent or transitory.

Once it realises that the sales will remain at the higher level, costs fall again as new staff are hire and overtime declines.

[NOTE: the DISCUSSION NEXT, TURNS TO THE CLASSICAL VARIANT]

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’ve spent 20+ years wondering when the economics I learned in college (B.A. 1991) would ever be useful. Now I realize that most of it never will. Luckily, I have forgotten most of it. I wish your textbook had been around then. Is there any chance tomorrow’s questions will not rely on an ultra-specific use of the language? I’m pretty sure most of my wrong answers would get at least half credit if what I thought you were asking was what you say you were.

Boy, am I looking forward to this.

My suggestion for this text book is to segregate out the neoclassical discussion to a sidebar (or perhaps chapter appendix). I believe this will make this text book more versatile without increasing the work load of the authors. The professor/student/reader will now have 3 different options to go over the material:

1) A “quicky” MMT macro course by ignoring the segregated neoclassical material. This will give s/he a good summary of the interrelations of employment, interest rates, money etc without having to hear about the ‘Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity’ and other neoclassical nonsense. I think that is acceptable in a MMT textbook.

2) “Issues in Macro economic theory” can be highlighted and contrasted by focusing on the segregated issues.

3) “Read all” which is the material as presently constituted.

Bill, I hope you find this suggestion helpful.

Best Wishes Glenn

“The theory of production we present here …”

TO

“Given the relative costs of labour and capital, …”

Is that in the post twice?

I like Glenn’s suggestion. One possible additional benefit to it might arise where in some section, an issue exists, but including it in-line would be too disruptive to the flow of the concept bring developed. I think (as obviously you do also) that including these issues is critical, as they provide a sense of the historical development of economic thought, and in doing so, present the field as more of a living entity instead of simply a bunch of rules and equations to remember. Just because the older views were incorrect doesn’t mean they should be forgotten. That would be too, well, neoclassical.

The micro foundations for this looks like Sraffa’s Law of Returns under Competitive Conditions.

I think it would be a good idea to put the data in there showing the level of capacity utilisation. It is, in fact, alarmingly low from the perspective of neoclassical economics but is eminently sensible from Sraffa’s point of view because prices are determined by a mark-up on costs of production and output by demand where products are differentiated and there is consumer loyalty.

Larger levels of sales will means

Think Glenn’s and Benedict’s suggestions are worth thinking about. I would also add boxed sections, as have appeared in many other books, perhaps most notably in the door stop, Gravitation, by Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler, a great book. They included, in these boxes, bio-bites of important physicists relevant to the discussion, other historical asides, and the like.

If you are going to include any tricky equations, I would recommend a look at A Student’s Guide to Maxwell’s Equations by Daniel Fleisch (2008). This is I think a superb model to imitate, but not done much at all.

Another thing I would love to see is it written in a style unlike that of the standard textbook. Your blog is lively and I would hate to see your style dampened by any idea that the text has to be written in a textbook style, while agreeing that a blog is a blog and a textbook a textbook. I would think that the book’s style must avoid at all costs being deadening, although I am sure you will try hard to avoid this.

I would love your book to be a best seller, like Gravitation (and it is over a thousand pages), and I see no reasons it can’t be. Many of the non-mainstream colleagues in your field can’t write very well, though not as badly as some sociologists and anthropologists, one of the worst of whom was Talcott Parsons. And I would hate your book to be seen as being an any way ‘like them’. One way perhaps of avoiding this might be to have a great cover, which publishers like Routledge never achieve, deliberately so. I am sure you have thought of this already.

Not only must the book be a substantial contribution to the field, which it obviously will be, but it must also be one that students will WANT to read because they like reading it, no matter how technical some of it is.

For what they are worth, these are some thoughts that have come to mind while reading your delightful posts. It would be terrific were you and Randy to become the academic Pecoras of our time.

Great post again. I have been trying to work this stuff out: this is very clear and useful. I am a little out of my depth, here, but I am in a bit of a quandary when I read this, because I can think of at least one sector where the Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity DOES seem to apply, oil extraction in the TarSands in Western Canada, where productivity has declined for a decade (while profits exploded). The theory of production that you present assumes that economies are rarely at full employment and the existing capital stock is rarely fully utilised (all of which makes sense to me). However, might there be good reason to present the presumption of Diminishing Marginal Productivity as applying in special cases where a regional economy is nearing full employment, and where the existing capital stock is fully used?

A couple of things:

Firstly, there are about a dozen paragraphs that are presented twice. Starting with “The theory of production ….” to the paragraph ending “… in the comping production period”. Presumably this is a blog posting issue.

Secondly, I like Sean’s suggestion of using capacity utilization as empirical evidence because it is commonly reported in the business press and quite often the journalist/commentator will say that 80% is considered a rough guide; more suggests inflation, less suggests a slowing economy and possible unemployment. I realize it is a little of topic but it may do as supplemental evidence perhaps, again, as a side bar?

Cheers.

“However, might there be good reason to present the presumption of Diminishing Marginal Productivity as applying in special cases where a regional economy is nearing full employment, and where the existing capital stock is fully used?”

Possibly it could apply in highly commodified markets. Those that are closest to the pure markets of theory.

And that’s the problem. Traditional economics is so enamoured with the purity of competition and markets that there is a tendency to believe that all markets operate like that or would do if there weren’t some ‘impurity’ in the way.

However anybody who has done any business would recognise the approach that Bill lays out above. It’s the commodity markets that are odd.

Will there be a chapter that differentiates Microeconomics from Macroeconomics ? Because it would appear many people struggle to tell the difference.

Thanks, Neil, once again.

One comment:

(1) “This is the so-called Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity and allows economists of this persuasion to postulate an increasing marginal cost relationship with respect to output (costs increase at an increasing rate as more output is produced).”

Repetition. Would read better if you wrote something like “…(costs RISE at an increasing rate as more…”.

“However, might there be good reason to present the presumption of Diminishing Marginal Productivity as applying in special cases where a regional economy is nearing full employment, and where the existing capital stock is fully used?”

I’m not sure that any business would operate at full capacity for any sustained period of time. Think about it. They’d have to turn away customers (towards competitors) every time there was an increase in demand.

Neil mentions commodities markets. I guess oil is the most obvious. But we all know the Saudis don’t operate at full capacity. And as for diamonds and the like these are often just scattered about the place and people are left to forage and sell their findings to capitalists. There certainly is no serious shortage of shovels — even in Angola.

I just don’t find the assumption of full capacity remotely credible. Even at full employment producers still have to factor in rising import markets and population growth.

@Philip Pilkington

Very interesting. But on the other hand, I don’t think (I am not sure though) that oil firms in Alberta, especially before the economic downturn, were facing constant marginal returns. There was serious wage inflation in the province on the cusp of the downturn, a housing shortage, and I don’t think that new drilling facilities can be put very quickly.

“Cutting wages would only redistribute total revenue towards profits, which might damage aggregate demand as workers will have less income to spend.”

but cutting wages could also help firms not to delocalize, and that adds to aggregate demand

“I’m not sure that any business would operate at full capacity for any sustained period of time. Think about it. They’d have to turn away customers (towards competitors) every time there was an increase in demand.”

That happens Philip. It is an entirely realistic scenario.

There are businesses out there who are happy to be ‘big enough’. Hairdressers are a classic case.

The assumption of competition is a dangerous one. Very often in business it is about getting your own little patch and then sitting on it. You can find whole industries where a group of businesses settle on their own little patch and then quietly get on with it – referring customers to each other in an entirely egalitarian manner.

It’s not a cartel, its not collusion. It’s just an understanding that everybody has to eat, and that some people are good at one thing and not at another.

The way real business works is often ‘co-opertition’.

Fight to the death competition is really quite unusual.

Neil: There are businesses out there who are happy to be ‘big enough’…. The assumption of competition is a dangerous one. Very often in business it is about getting your own little patch and then sitting on it.

As a former adviser to small start-ups, primary advice is to seek niche markets and are not worth it to bigger fish to enter. Even patents and other intellectual property rights have to be defended, and that is time-consuming and expensive.

A small start-up must carefully choose its niche so as to be able to protect it one becomes more successful and gets noticed. Otherwise, you are going to be gobbled up by economies of scale. Guaranteed. Late-stage capitalism tends toward monopoly capital.

The notion of perfect competition in perfect markets based on “the invisible hand” of pursuit of self-interest is a theoretical ideal that doesn’t apply in practice.

“It’s not a cartel, its not collusion. It’s just an understanding that everybody has to eat, and that some people are good at one thing and not at another.”

I spent most of my career working for one party in a WW duopoly. There was such an enormous technical and capital barrier to entry no-one else could break in. A venture capital fund even lost over a billion trying. Senior staff often moved between the two companies. One of the senior executives was asked a question “why doesn’t company X (who had lower market share) compete with us more on price?”. His response included the term “unspoken agreement”. It seems there is a common understanding in both companies not to embark on a price war. Just price low enough to keep out other entrants.

Corporate CEO’s seems to be interested in telling good stories to the shareholders. Little bit of growth is fine, as market generally grows. It makes no sense to endager their own quite well paid position by taking on uneccessary risk, like entering on foreign markets with unfamiliar legal frameworks and such. If there is any sort of trouble they may lose their jobs. Thats why profit maximization does not happen in real life.

I hope this thread isn’t dead.

“As production is increased when the firm believes that it can sell more output, unused machines are turned back on and unemployed workers are assigned to them. There is no reason to assume that output per unit of labour input on these machines would be any different to that derived from the plant that was kept active during the downturn.”

Respectfully, this is a misleading oversimplification. There is historical reason to expect that restarting plant that has been idle for some time will cost a surprisingly large quantity of man-hours and replacement parts to return to its former productivity. If you doubt me, ask almost any maintenance engineer over a beer (btw I’m not one).