Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday quiz – May 12, 2012 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The non-government sector are wealthier when a government issues bonds by the government to match its budget deficit.

The answer is False.

This answer relies on an understanding the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt within a fiat monetary system. That understanding allows us to appreciate what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

In this situation, like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

Ignoring any reserve requirements, a central bank will eliminate any need to conduct open market operations to ensure its target policy rate is achieved each day by paying a positive interest rate on overnight reserves.

The answer is False.

Mainstream macroeconomics textbooks tells students that monetary policy describes the processes by which the central bank determines “the total amount of money in existence or to alter that amount”.

In Mankiw’s Principles of Economics (Chapter 27 First Edition) he say that the central bank has “two related jobs”. The first is to “regulate the banks and ensure the health of the financial system” and the second “and more important job”:

… is to control the quantity of money that is made available to the economy, called the money supply. Decisions by policymakers concerning the money supply constitute monetary policy (emphasis in original).

How does the mainstream see the central bank accomplishing this task? Mankiw says:

Fed’s primary tool is open-market operations – the purchase and sale of U.S government bonds … If the FOMC decides to increase the money supply, the Fed creates dollars and uses them buy government bonds from the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the purchase, these dollars are in the hands of the public. Thus an open market purchase of bonds by the Fed increases the money supply. Conversely, if the FOMC decides to decrease the money supply, the Fed sells government bonds from its portfolio to the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the sale, the dollars it receives for the bonds are out of the hands of the public. Thus an open market sale of bonds by the Fed decreases the money supply.

This description of the way the central bank interacts with the banking system and the wider economy is totally false. The reality is that monetary policy is focused on determining the value of a short-term interest rate. Central banks cannot control the money supply. To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

The essential idea is that the “money supply” in an “entrepreneurial economy” is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply.

As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 (Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector plus all other bank deposits from the private non-bank sector) is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans. The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves. Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

With this background in mind, the question is specifically about the dynamics of bank reserves which are used to satisfy any imposed reserve requirements and facilitate the payments system. These dynamics have a direct bearing on monetary policy settings. Given that the dynamics of the reserves can undermine the desired monetary policy stance (as summarised by the policy interest rate setting), the central banks have to engage in liquidity management operations.

What are these liquidity management operations?

Well you first need to appreciate what reserve balances are.

The New York Federal Reserve Bank’s paper – Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy said that:

… reserve balances are used to make interbank payments; thus, they serve as the final form of settlement for a vast array of transactions. The quantity of reserves needed for payment purposes typically far exceeds the quantity consistent with the central bank’s desired interest rate. As a result, central banks must perform a balancing act, drastically increasing the supply of reserves during the day for payment purposes through the provision of daylight reserves (also called daylight credit) and then shrinking the supply back at the end of the day to be consistent with the desired market interest rate.

So the central bank must ensure that all private cheques (that are funded) clear and other interbank transactions occur smoothly as part of its role of maintaining financial stability. But, equally, it must also maintain the bank reserves in aggregate at a level that is consistent with its target policy setting given the relationship between the two.

So operating factors link the level of reserves to the monetary policy setting under certain circumstances. These circumstances require that the return on “excess” reserves held by the banks is below the monetary policy target rate. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also sets a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank.

Many countries (such as Australia and Canada) maintain a default return on surplus reserve accounts (for example, the Reserve Bank of Australia pays a default return equal to 25 basis points less than the overnight rate on surplus Exchange Settlement accounts). Other countries like the US and Japan have historically offered a zero return on reserves which means persistent excess liquidity would drive the short-term interest rate to zero.

The support rate effectively becomes the interest-rate floor for the economy. If the short-run or operational target interest rate, which represents the current monetary policy stance, is set by the central bank between the discount and support rate. This effectively creates a corridor or a spread within which the short-term interest rates can fluctuate with liquidity variability. It is this spread that the central bank manages in its daily operations.

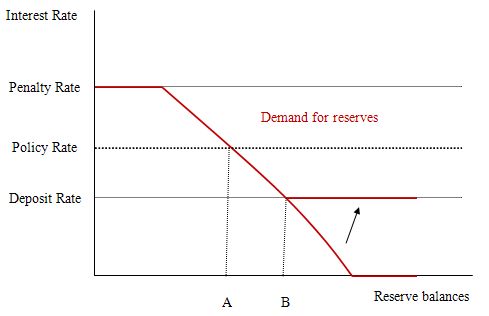

So the issue then becomes – at what level should the support rate be set? To answer that question, I reproduce a version of the diagram from the FRBNY paper which outlined a simple model of the way in which reserves are manipulated by the central bank as part of its liquidity management operations designed to implement a specific monetary policy target (policy interest rate setting).

I describe the FRBNY model in detail in the blog – Understanding central bank operations so I won’t repeat that explanation.

The penalty rate is the rate the central bank charges for loans to banks to cover shortages of reserves. If the interbank rate is at the penalty rate then the banks will be indifferent as to where they access reserves from so the demand curve is horizontal (shown in red).

Once the price of reserves falls below the penalty rate, banks will then demand reserves according to their requirments (the legal and the perceived). The higher the market rate of interest, the higher is the opportunity cost of holding reserves and hence the lower will be the demand. As rates fall, the opportunity costs fall and the demand for reserves increases. But in all cases, banks will only seek to hold (in aggregate) the levels consistent with their requirements.

At low interest rates (say zero) banks will hold the legally-required reserves plus a buffer that ensures there is no risk of falling short during the operation of the payments system.

Commercial banks choose to hold reserves to ensure they can meet all their obligations with respect to the clearing house (payments) system. Because there is considerable uncertainty (for example, late-day payment flows after the interbank market has closed), a bank may find itself short of reserves. Depending on the circumstances, it may choose to keep a buffer stock of reserves just to meet these contingencies.

So central bank reserves are intrinsic to the payments system where a mass of interbank claims are resolved by manipulating the reserve balances that the banks hold at the central bank. This process has some expectational regularity on a day-to-day basis but stochastic (uncertain) demands for payments also occur which means that banks will hold surplus reserves to avoid paying any penalty arising from having reserve deficiencies at the end of the day (or accounting period).

To understand what is going on not that the diagram is representing the system-wide demand for bank reserves where the horizontal axis measures the total quantity of reserve balances held by banks while the vertical axis measures the market interest rate for overnight loans of these balances

In this diagram there are no required reserves (to simplify matters). We also initially, abstract from the deposit rate for the time being to understand what role it plays if we introduce it.

Without the deposit rate, the central bank has to ensure that it supplies enough reserves to meet demand while still maintaining its policy rate (the monetary policy setting.

So the model can demonstrate that the market rate of interest will be determined by the central bank supply of reserves. So the level of reserves supplied by the central bank supply brings the market rate of interest into line with the policy target rate.

At the supply level shown as Point A, the central bank can hit its monetary policy target rate of interest given the banks’ demand for aggregate reserves. So the central bank announces its target rate then undertakes monetary operations (liquidity management operations) to set the supply of reserves to this target level.

So contrary to what Mankiw’s textbook tells students the reality is that monetary policy is about changing the supply of reserves in such a way that the market rate is equal to the policy rate.

The central bank uses open market operations to manipulate the reserve level and so must be buying and selling government debt to add or drain reserves from the banking system in line with its policy target.

If there are excess reserves in the system and the central bank didn’t intervene then the market rate would drop towards zero and the central bank would lose control over its target rate (that is, monetary policy would be compromised).

As explained in the blog – Understanding central bank operations – the introduction of a support rate payment (deposit rate) whereby the central bank pays the member banks a return on reserves held overnight changes things considerably.

It clearly can – under certain circumstances – eliminate the need for any open-market operations to manage the volume of bank reserves.

In terms of the diagram, the major impact of the deposit rate is to lift the rate at which the demand curve becomes horizontal (as depicted by the new horizontal red segment moving up via the arrow).

This policy change allows the banks to earn overnight interest on their excess reserve holdings and becomes the minimum market interest rate and defines the lower bound of the corridor within which the market rate can fluctuate without central bank intervention.

So in this diagram, the market interest rate is still set by the supply of reserves (given the demand for reserves) and so the central bank still has to manage reserves appropriately to ensure it can hit its policy target. If there are excess reserves in the system in this case, and the central bank didn’t intervene, then the market rate will drop to the support rate (at Point B).

So if the central bank wants to maintain control over its target rate it can either set a support rate below the desired policy rate (as in Australia) and then use open market operations to ensure the reserve supply is consistent with Point A or set the support (deposit) rate equal to the target policy rate.

The answer to the question is thus False because the simple act of paying interest on reserves does not necessarily eliminate the need for open market operations. It all depends on where the support rate is set. Only if it set equal to the policy rate will there be no need for the central bank to manage liquidity via open market operations.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Understanding central bank operations

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 3:

Ignoring any reserve requirements, bank reserves will be higher than otherwise if the central bank pays a positive return on overnight reserves held by the commercial banks equal to its current policy rate.

The answer is True.

This question was clearly related to the Question 2 and so some of the essential information required to understand the answer here is presented there.

The payment of a positive return on overnight reserves equal to the current policy rate will significantly reduce interbank activity. Why? Because the banks will not have to worry about earning non-competitive returns on excess reserves. When there are excess reserves in the system, which means the level of reserves is beyond that desired by the banks for clearing purposes, the banks which hold excesses seek to lend them out on the interbank (overnight) market.

In the absence of a support rate (positive return on overnight reserves) and any central bank liquidity management operations (open market purchases in this case), the competition in the interbank market will drive the market rate of interest down to zero on overnight funds. It should be noted that these transactions between the banks will not eliminate a system-wide excess reserve situation.

The competition will redistribute the excess between banks but will not eliminate it. A vertical transaction between the government and non-government sectors is the only way such an excess can be eliminated.

Please see the suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for a detailed explanation of the difference between vertical transactions (between the government and non-government sectors) and horizontal transactions (between non-government entities).

Clearly, the central bank loses control of its monetary policy setting in this case (unless the target is a zero short-term interest rate) unless it steps in and eliminates the excess reserves by selling government debt to the banks. This provides the banks with an interest-bearing financial asset in exchange for the zero-interest bearing reserves.

Once the central bank offers a support rate the situation changes If the support rate on overnight reserves is set equal to the current policy rate then the banks have no incentive to engage in interbank lending. Some banks may still seek overnight funds in the interbank market if they are short of reserves but in general activity in that market will be significantly reduced.

Further, the opportunity cost of holding excess reserves is eliminated and so the banks have less need to minimise their holdings of reserve balance each day.

Any bank with reserves in excess of their short-term perceived clearing house requirements will still earn the market rate of interest on them.

As a consequence, the incentive to lend these funds is substantially reduced. Banks would only participate in interbank market if the rate they could lend at was above the market rate and below the central bank penalty rate.

So in this case, banks will tend to hold more reserves than otherwise to make absolutely sure they never need to access the discount window offered by the central bank which carries the penalty.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Understanding central bank operations

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 4:

When a country runs a small current account deficit and the private domestic sector is saving overall, the government budget balance will always be in deficit.

The answer is True.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

Refreshing the balances – we know that from an accounting sense, if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

The important point is to understand what behaviour and economic adjustments drive these outcomes.

The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down. The reference to a “small” external deficit was to place doubt in your mind. In fact, it doesn’t matter how large the external deficit is for this question.

Assume, now that the private domestic sector (households and firms) seeks to save overall, which is a different thing to saying that households save out of disposable income.

Households can save out of disposable income but the private domestic sector may still be spending more than income if investment flow is larger than the flow of saving, and vice versa.

So assume that the private domestic sector is succesful in spending less than its overall income. Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income and firms might cut back investment spending.

The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract – output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms’ investment plans – they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public budget balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its saving ratio then the contracting income will clearly push the budget into deficit.

So we would have an external deficit, a private domestic surplus and a budget deficit.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 5 – Premium Question:

Various governments are imposing austerity budgets on their economies. In Britain and the US, even “progressives”are supporting cutting net spending but prefer to focus on tax increases while the “conservatives” are recommending spending cuts and privatisation. In terms of the initial impact on national income, which policy option will be more damaging – a tax increase which aims to increase tax revenue at the current level of national income by $x or a spending cut of $x?

(a) Tax increase

(b) Spending cut

(c) Both will be equivalent

(d) There is not enough information to answer this question

The answer is Spending cut.

The question is only seeking an understanding of the initial drain on the spending stream rather than the fully exhausted multiplied contraction of national income that will result. It is clear that the tax increase increase will have two effects: (a) some initial demand drain; and (b) it reduces the value of the multiplier, other things equal.

We are only interested in the first effect rather than the total effect. But I will give you some insight also into what the two components of the tax result might imply overall when compared to the impact on demand motivated by an decrease in government spending.

To give you a concrete example which will consolidate the understanding of what happens, imagine that the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income is 0.8 and there is only one tax rate set at 0.20. So for every extra dollar that the economy produces the government taxes 20 cents leaving 80 cents in disposable income. In turn, households then consume 0.8 of this 80 cents which means an injection of 64 cents goes into aggregate demand which them multiplies as the initial spending creates income which, in turn, generates more spending and so on.

Government spending cut

A cut in government spending (say of $1000) is what we call an exogenous withdrawal from the aggregate spending stream and this directly reduces aggregate demand by that amount. So it might be the cancellation of a long-standing order for $1000 worth of gadget X. The firm that produces gadget X thus reduces production of the good or service by the fall in orders ($1000) (if they deem the drop in sales to be permanent) and as a result incomes of the productive factors working for and/or used by the firm fall by $1000. So the initial fall in aggregate demand is $1000.

This initial fall in national output and income would then induce a further fall in consumption by 64 cents in the dollar so in Period 2, aggregate demand would decline by $640. Output and income fall further by the same amount to meet this drop in spending. In Period 3, aggregate demand falls by 0.8 x 0.8 x $640 and so on. The induced spending decrease gets smaller and smaller because some of each round of income drop is taxed away, some goes to a decline in imports and some manifests as a decline in saving.

Tax-increase induced contraction

The contraction coming from a tax-cut does not directly impact on the spending stream in the same way as the cut in government spending.

First, imagine the government worked out a tax rise cut that would reduce its initial budget deficit by the same amount as would have been the case if it had cut government spending (so in our example, $1000).

In other words, disposable income at each level of GDP falls initially by $1000. What happens next?

Some of the decline in disposable income manifests as lost saving (20 cents in each dollar that disposable income falls in the example being used). So the lost consumption is equal to the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income times the drop in disposable income (which if the MPC is less than 1 will be lower than the $1000).

In this case the reduction in aggregate demand is $800 rather than $1000 in the case of the cut in government spending.

What happens next depends on the parameters of the macroeconomic system. The multiplied fall in national income may be higher or lower depending on these parameters. But it will never be the case that an initial budget equivalent tax rise will be more damaging to national income than a cut in government spending.

Note in answering this question I am disregarding all the nonsensical notions of Ricardian equivalence that abound among the mainstream doomsayers who have never predicted anything of empirical note! All their predictions come to nought.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

With regard to question 5: In your argument you have used a uniform marginal propensity to consume (MPC), 80% in your example. Let’s consider a couple of extreme examples.

1. Suppose the government wants to reduce expenditure and notices that it is paying a lot for high profile economic advisors. It then reduces expenditure on them. Since they are wealthy (sorry, teasing a bit here), their MPC is quite low. When they reduce their expenditure in turn, it will be on luxury goods such as fine wine. The vigneron in turn is relatively wealthy and also has a low propensity to consume (at least in the economic sense, not in reference to his wine consumption). The effect on overall demand is therefore quite low.

2. Now suppose that the government increases taxes especially on the low income earners (Heaven forbid!). Their MPC is quite high, close to one. Their reduction in expenditure will be on basic items and will affect supermarket workers whose MPC is also high. The compounded effect is still high so that the overall effect on demand is relatively high.

Comparing these two examples, we see that increasing tax is worse. If we assume that the government acts reasonably, the reduction of expenditure has a worse effect, but that itself is an unreasonable assumption. And I am desperately trying to justify my original answer to the question, which was (d).

Today’s “corridor” was yesterday’s “Fed Funds Bracket Racket” (the operational technique used by the NY Fed’s “trading desk” when it first emerged in 1965). The brackets for these two rates were set: -buying operations in the open market were used to prevent rates from rising above the bracket, -selling operations when rates tended to fall below the bottom of the bracket. The effect of these misguided procedures was to allow any and all banks to acquire added legal reserves (legal lending capacity) by simply entering the federal funds market and bidding up the federal funds rate to the “trigger” level.

Since the demand for bank credit, and subsequent increase in the money supply, is reinforcing and not self regulatory, an inflationary environment was quickly fostered. Consequently, the prevailing pressures in the credit markets were on the top side of the federal funds brackets. Demands for bank credit to finance real estate and commodity speculation soon became excessive.

Monetary flows (money times its turnover rate) expanded sharply. Price rises as a consequence accelerated, and more and more bank credit was required to finance all transactions. In other words, the Fed’s technical staff, by adhering to the false Keynesian theory – that the money supply could be properly controlled through the manipulation of interest rates, specifically the federal funds rate — lost control of both the money supply and the federal funds rate.

The money supply (and thus commercial bank credit), can never be managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit (i.e., thru pegging the interest rate on governments; or thru “floors”, “ceilings”, “corridors”, “brackets”, etc). Keynes’s liquidity preference curve is a false doctrine.

“Central banks cannot control the money supply”

While it is true that commercial bank lending & investing (fractional reserve banking), is not now constrained — it was not true when legal reserves were “binding” (the system’s expansion coefficient was operative between 1942 until 1995). Today, increasing levels of vault cash (larger ATM networks), retail deposit sweep programs, fewer applicable deposit classifications (including the “low-reserve tranche” & “exemption amounts”), & lower reserve ratios, & most recently “Reserve Simplification” procedures have combined to remove most reserve, & reserve ratio, restrictions.

While injecting reserves is not automatically accompanied by an increase in the money stock, the undue draining of District Reserve inter-bank balances can still trigger a multiple contraction of money & credit (aka the Great Recession).

“You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink”

Keynes thought there was no difference between money & liquid assets. And all those on the FED’s technical staff are Keynesians.

IOeRs alter the construction of a normal yield curve, they INVERT the short-end segment of the YIELD CURVE – known as the money market.

SEE: The inverted Eurepo curve spells trouble

http://soberlook.com/2012/05/inverted-eurepo-curve-spells-trouble.html

The 5 1/2 percent increase in REG Q ceilings on December 6, 1965 (applicable only to the commercial banking system), is analogous to the .25% remuneration rate on excess reserves today (i.e., the remuneration rate @ .25% is higher than the daily Treasury yield curve almost 2 years out – .27% on 4/18/12).

In 1966, it was the lack of mortgage funds, rather than their cost (like ZIRP today), that spawned the credit crisis & collapsed the housing industry. I.e., it was dis-intermediation (an outflow of funds from the non-banks).

Just as in 1966, during the Great Recession, the Shadow Banking System has experienced dis-intermediation (where the non-banks shrink in size, but the size of the commercial banking system stays the same)

“Securities purchased (and sold) by the Fed, for example, could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

But the Fed’s research staff missed the corollary – IOeR’s “could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

SEE: http://www.chicagofed.org/digital_assets/others/events/2012/day_ahead/ennis_wolman.pdf The Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond didn’t understand the implications of their comments.

The fifth (in a series of rate increases), promulgated by the Board and the FDIC beginning in January 1957, was unique in that it was the first increase that permitted the commercial banks to pay higher rates on savings, than savings & loans & the mutual savings banks could competitively meet (like the CB’s IOeRs now compete with other financial assets [held by the non-banks], on the short-end of the yield curve).

Bankers, confronted with a remuneration rate that is higher (vis a’ vis), other competitive financial instruments, will hold a higher level of un-used excess reserves (i.e., will both 1. absorb existing bank deposits within the CB system, as well as 2. attract monetary savings from the Shadow Banks).

So IOeRs are not just a credit control device (offsetting the expansion of the FED’s liquidity funding facilities on the asset side of its balance sheet). But in the process ,they induce dis-intermediation (an economist’s word for going broke/bankrupt), in the Shadow Banks.

The effect of allowing IOeRs to “compete” with the returns generated from the financial assets held by the Shadow Banks, has been, and will be, to shrink the size of the Shadow Banks (as deregulation has in the last 50 years – with the exception of the GSEs).

However, disintermediation for the CBs can only exist in a situation in which there is both a massive loss of faith in the credit of the banks and an inability on the part of the Federal Reserve to prevent bank credit contraction, as a consequence of its depositor’s withdrawals.

The last period of disintermediation for the CBs occurred during the Great Depression, which had its most force in March 1933. Ever since 1933, the Federal Reserve has had the capacity to take unified action, through its “open market power”, to prevent any outflow of currency from the banking system.

Whereas disintermediation for the Shadow Banks (e.g., MMMFs), is predicated on their loan inventory (and thus can be induced by the rates paid by the commercial banks); i.e., the CBs earning assets, or IOeRs.