The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Athens burned, while I played Sudoku

Today, I am back in Greece. Yesterday, there was a confidential in-house “Staff Note” leaked from the Institute of International Finance, which purported to estimate the costs of a disorderly default on Greek government debt. Most of the paper was about ECB and related “contingent liabilities” which summed to around €1 trillion. However, once you understand the nature of those “contingent liabilities” in the context of the capacity of the ECB as the currency-issuer in the EMU and compare them with the real losses being endured by the Greek economy and its people, then you soon realise that the Greek government should reintroduce its own currency immediately. The European elites, however, are too busy playing Sudoku to appreciate that, ultimately, their ideologically-motivated austerity will not only impoverish Greece, but will also cause their whole monetary system to collapse.

The German Bild Magazine reported in its article (February 29, 2012) – Schäubles Sudoku-Szene hat Nachspiel für ARD – that the German public broadcasting network ARD was rebuked (RÜFFEL FÜR DIE ARD) for capturing the game-playing finance minister.

Doch diese Indiskretion des Kameramanns hat für die ARD ein Nachspiel!

Nach BILD-Informationen meldete sich das Bundestagspräsidium beim Sender und verwies auf die Hausordnung. Darin heißt es: „Die unautorisierte Ablichtung persönlicher Unterlagen in der Weise, dass diese lesbar sind, ist untersagt.”

Der Sender stimmte zu, die Szene nicht mehr zu zeigen und löschte sie sogar von seiner Internet-Seite.

The debate in the Bundestag was about the Greek bailout. The Finance minister was caught by ARD during the debate.

Apparently, a spokesperson for his office claimed that (Source):

… he was taking a well-deserved break from normal duties

One of his coalition partners said that “It never hurts to do brainteasers. However, you should ask yourself when the timing is appropriate”.

In the aftermath, the German government told ARD it was against the House rules to film such things: “The unauthorized photocopying of personal documents in a way that it is readable, is prohibited.” As a result, ARD was ordered to delete all material relating to this incident from its WWW-site.

You can see the YouTube video of a very sneaky finance minister – HERE.

The Bild article says that tablet computers are allowed in the Bundestag (“Einen Tablet-Computer zu benutzen, auch am Rednerpult, ist erlaubt”) but laptops are not (“Laptops zu benutzen”). Among other things banned in the German parliament is “unwürdige Kleidung (z.B. Shorts)” (undignified clothing, for example, shorts).

Meanwhile, Bloomberg article (March 2, 2012) – Troika to Have Permanent Presence in Greece, Wieser Tells Format – reported that Greece will now be an occupied state. The Austrian head of the Eurogroup Working Group, one Thomas Wieser told a journalist that:

A permanent presence of the troika on site to monitor the reforms will definitely be the case for several years …

But the real clincher was that Wieser was reported as saying that Greece will have to wait until the middle of this century before:

…. growth will “speed up” …

So in the meantime the Greeks might as well get their iPads out and play Sudoku!

This reminds me of something I read in the past. Chicago monetarist Milton Friedman was asked during the high unemployment in the 1970s how long it would take for unemployment to fall back to its so-called (mythical) natural rate if central banks embraced his dis-inflation recommendations. He said about 15 years. So 10 or more percent unemployment was expected for 15 years … as the way in which the mainstream models of self-correction work.

I guess the unemployed can also play Suduko given that their unemployment benefits allow them to luxuriate in material splendour!

A Greek friend sent me some factual data from his reading of one newspaper in Greece yesterday for consideration. Here it is (thanks Vassilis). Other than the comments by Mr Wieser, which as you would expect attracted wide coverage in Greece consider the following articles.

The Greek-edition of Kathimerini published an article (March 6, 2012) – Γραμμή βοήθειας για την κατάθλιψη (Helpline for depression) – which details the descent in mental illness in Greece as a result of the crisis.

It tells us that the helpline for depressed or suicidal people received 40 per cent more calls in 2011 than in 2010. The situation is the same in the general helpline.

According to its operators, people calling to seek advice and information on elementary survival issues, like getting good or shelter, has increased from 2 per cent in 2010 to 4.6 per cent in 2011. And the percentage of people calling to seek advice on basic health and insurance issues rose from 11.5 per cent to 19.6 per cent. The population proportions understate the true situation because only a small portion of the desperate or destitute Greeks seek help in this way.

From the Ekathimerini article (March 6, 2012) – Hostage-taker at northern Greece factory surrenders – we read that:

A man who stormed a plastics factory in northern Greece from which he had been fired, shooting and wounding three people and taking another two hostage, surrendered to police around 1 a.m. on Friday morning.

Apparently, the mainstream press has already started smearing the hostage taker because he was about to get married for the third time.

I particularly liked this story in Ekathimerini (March 6, 2012) – To reach reforms, don’t take a cab – which bears on the consistency of those who are arguing for widespread “structural” reforms in Greece based on their claim that the country is crippled because it is non-competitive.

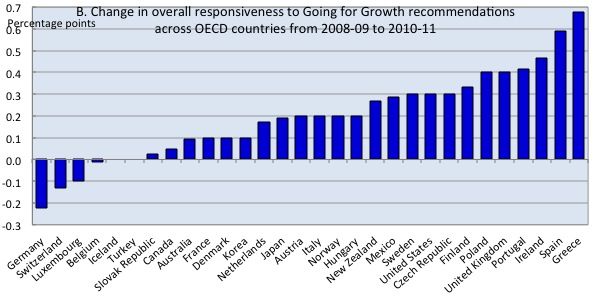

The press story reports on the recent OECD article (February 24, 2012) – Structural reforms can make the difference as countries rebound from crisis. The article summarises the findings in the Going for Growth report.

The OECD claim that the:

… that the pace of reform has accelerated where it is needed most – in the European countries hardest hit by the sovereign debt crisis, including Greece, Ireland, Portugal and most recently, Spain and Italy.

The Kathimerini article notes that according the OECD “Greece is a world leader in structural reforms” but it still has “lot of catching up to do”:

But while the article says that some of the reforms “make absolute sense” the plethora of reforms demanded by the Troika are questionable.

They consider the “liberalization of dozens of closed professions” and show that in certain occupations the reforms make no sense at all.

As an example, they consider taxis:

Greece has been agonizing for more than a year over how to open up this sector. Plans for total liberalization have been drawn up, agreed and then scrapped in favor of a watered-down version. There is something disconcerting about the fact that the limited number of cab licenses issued by the government meant these pieces of paper became a tradable commodity, which turned some cabbies into investors rather than drivers.

But then they cite a recent Financial Times article which likens the design of the taxi industry in Greece to that which operates in New York. We read that the taxi industry in:

… that symbol of free market, capitalist culture … [New York] … does things pretty much the way they’re done in Greece.

The New York system of licensing is replicated throughout the world.

The point is obvious – selective treatment – “Given that Athens and New York, which is not known for its aversion to the market, operate similar systems for taxi licenses, isn’t it odd that there has been so much pressure for Greece to free up this profession?”

And finally, this article (March 5, 2012) – Value of properties auctioned soared to 4.5 billion euros recounts that forced real estate sales are rising (“(c)onfiscations of properties more than doubled within three years” and “the combined value of bouncing checks and unpaid bills of exchange” has soared – up by 15 per cent in 2011).

Then there was this leaked (confidential report) from the Institute of International Finance – Implications of a Disorderly Greek Default and Euro Exit (1.3 mbs – thanks to Jared for text version). You can also read it at HERE but you are unable to download it.

The IIS Staff Note says that if there was “a disorderly default on Greek government debt … would impose significant further damage, already beleaguered Greek economy racing serious social costs.”

And apart from saying that the “most obvious immediate spillover … that it would put a major question market against the quality of a sizeable amount of Greek private sector liabilities”, the IIS report is about the “official sector in the rest of the Euro area”.

They outlined a series of “contingent liabilities” which they say would not exceed €1 trillion.

These “contingent liabilities” include “direct losses on Greek debt holdings (€73 billion)”, “sizeable potential losses by the ECB (€177 billion)”, “likely need to provide substantial additional support to both Portugal and Ireland … Spain and Italy (€730 billion)”, “sizeable bank recapitalisation costs (€160 billion)”, “lost tax revenues from weaker Euro Area growth”, ” lower tax revenues resulting from lower global growth”.

When you actually examine these “costs” and understand the nature of them, then the conclusion you might draw is that, given the scale of real damage being done in Greece by the fiscal austerity, these contingent liabilities are not of the same scale.

The IIS Staff Note thinks that the most profound issue relates to “increased involvement of the ECB in supporting the euro area financial system” which “would lead to significant losses and strains on the ECB itself” and the Greek government defaulted in a disorderly fashion.

They claim that:

When combined with the strong likelihood that a disorderly Greek default would lead to the hurried exhort of Greece from the Euro Area, this financial shock to the ECB could raise significant stability issues about the monetary union.

If the “financial shock to the ECB” is all that they are worried about, then they are not worried about very much.

The ECB is the currency-issuer of the Euro. It can never run out of Euros.

Willem Buiter noted in his 2008 Discussion Paper – Can Central Banks Go Broke? – that in “the usual nation state setting” there is a unique “national fiscal authority” (treasury) which “stands behind a single national central bank”. He concludes in this situation that:

There can be no doubt … the fiscal authorities are, from a technical, administrative and economic management point of view, capable of extracting and transferring to the central bank the resources required to ensure capital adequacy of the central bank should the central bank suffer a severe depletion of capital in the performance of its lender of last resort and market maker of last resort functions.

Does this mean that central banks cannot go broke? Answer: no.

Willem Buiter provides the qualification that is essential:

… the central bank can always bail out any entity – including itself – through the issuance of base money – if the entity’s liabilities are denominated in domestic current and nominally denominated (that is, not index-linked). If the liabilities of the entity in question are foreign-currency-denominated or index-linked, a bail-out by the central bank may not be possible.

Which is the standard Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) definition of a risk-free sovereign government – one that only issues liabilities in its own currency. If the consolidated government sector – the central bank and the treasury – issue liabilities (for example, take on debt) – that is denominated in a foreign currency, then insolvency becomes a possibility.

What about the Eurozone, where there is no fiscal authority? In the Eurozone, the pecking order is that the member state treasuries are deemed to guarantee their own national central banks which “own” the ECB and which provide lender of last resort facilities to their own banking systems. There is no fiscal authority backing the ECB but despite all the legal niceties (complexities) involved in how the national central banks might carry out their lender of last resort duties, the reality is that the ECB is the ultimate lender of last resort in the EMU

The other point to note (which is made by Buiter) is that it :

… is not necessarily the case that a central bank goes bankrupt even if its equity capital is completely depleted by its engagement in unorthodox monetary policies. The reason is that there are differences between central banks and commercial banks and a static visual inspection of the central bank balance sheet does not convey a complete picture.

Why is that?

Consider the US Federal Reserve which could easily buy all the outstanding US federal government if it wanted to and if the Federal Reserve lost capital it could simply issue new currency to replenish it.

The same logic goes for the ECB – it alone creates the Euro currency. It can never go bankrupt.

While the mainstream economists would consider this to be dangerously inflationary if the central bank acted in this way the point is that at least that observation (erroneous or not) takes the debate beyond the inane level of insolvency.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

So the argument that the the argument that the ECB is exposing itself to credit risk (buying up dodgy assets) and could go broke is erroneous.

Please read my blogs – The US Federal Reserve is on the brink of insolvency (not!) and Better off studying the mating habits of frogs – for more discussion on this point.

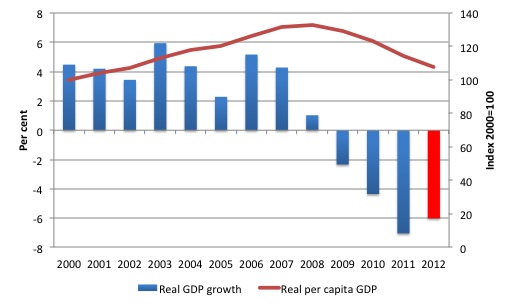

The following graph combines IMF World Economic Outlook data (from the September 2011 database) with latest population and real GDP estimates from the EU and the IMF. It shows real GDP growth (per cent) – left hand axis since 2000 (entry into the Eurozone) and real GDP per capita (red line – index = 100 at 2000 – right axis). The red bar is the 2012 estimate (a decline of 6 per cent).

I have been checking each time the real GDP data comes out as to where Greece is in relation to the past. Each time I check the situation gets worse. Real GDP per capita is now back to the 2002 level and falling. Soon, there will be no real gains as a result of entering the Euro (if per capita GDP is considered).

Of-course, with all the hacking of wages and pensions and other public spending, the level of inequality that real GDP per capita figures obscure will rise. So already, it is likely that millions of Greek citizens are vastly poorer than before they entered the Eurozone and this is likely to get worse.

If Mr Wieser’s predictions play out then poverty rates in Greece are certain to rise. Already, Eurostat reports that the poverty rate in Greece had risen to 27.7 per cent in 2010. Some 33 per cent of Greeks over the age of 65 are in poverty.

Further, most of the IIF “cost” estimates noted above are, in fact, zero “cost” contingencies because the ECB can issue the currency without cost. Costs should be thought of in real terms. There are no real costs involved in the ECB extending its SMP, or extending long-term credit to the banks, etc.

I know that the majority of Greeks still think the Euro is a good thing for them although they hate the imposed fiscal austerity. That juxtaposition just tells me that they are ill-informed about the true nature of their problem.

Consider the following arithmetic.

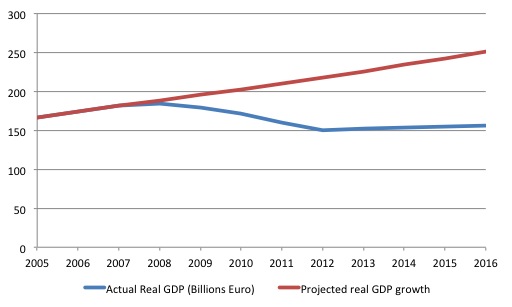

Average real GDP growth between 1994 and 2007 in Greece was 3.64 per cent per annum. Imagine that the Depression (I now use that term for Greece) had not have occurred and the Greek economy had have continued growing at that average pace.

The following graph shows the comparison between actual real GDP growth (blue line) and projected real GDP growth (in the absence of the Depression). The blue line is based on actual data up to 2011 and then used the projected 6 per cent contraction in 2012, followed by a 1 per cent growth rate to 2016 (which I think is optimistic given the way things are going at present).

The gap between the two lines is the lost real national income as a result of the Depression which has been created by the fiscal austerity. If you sum the annual losses (which I think are conservative estimates) then the total losses to 2016 alone would be of the order of 510 billion Euros.

Then you have add in all the real costs for people that extend beyond the lost income.

If the Greek people really understood that these alleged “financial costs” for the ECB and others that the neo-liberals elevate to top priority were in fact a sham, and understood the design flaws in the EMU, then would they really continue to support retention of the Euro?

If they did, then they deserve all they get – which will be decades of stagnant growth and increased poverty.

I am not one for conspiracy theories except I do consider class-based analysis to be an essential organising framework for understanding what is going on.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) tells us how the economy operates and the consequences of different actions and provides a guidance to the best policy solutions for certain given macroeconomic goals (such as full employment and price stability).

But you have to dig deeper to understand why governments choose the policies that they do.

A recent UK Guardian article (March 5, 2012) – What now for Greece – collapse or resurrection? – offers an interesting view on that question.

The by-line for the article was “Neoliberal economics planned in Brussels and Berlin will push Greece into third-world working conditions”.

The author notes the poor forecasting performance of the mainstream of my profession:

The reporting of the Greek tragedy over the last couple of years gives the impression that economics is a master science. Yet, the mainstream economists who gave Lehman Brothers a certificate of rude health just before its collapse, predicted that by 2012 the Greek economy would start growing. The economy shrank by 7% last year and a further 6% contraction is predicted for this year, with worse to come. This is the fastest slump in recent times. The discipline of this type of economics is often closer to a confidence trick than a science.

Please read my blog – 100 per cent forecast errors are acceptable to the IMF – for more discussion on this point.

If you examine the major macroeconomic textbooks that students using university studies, it will become readily apparent that the theory they are exposed to were incapable of predicting the crisis.

A further examination of the mainstream macroeconomics literature over the last 15 years would lead you to the same conclusion.

Further, the movements in the aggregates since the crisis (real GDP, interest rates, inflation, budget deficits, public debt ratios, etc) are totally at odds with the predictions that one would glean from the mainstream macroeconomic models.

It is not too far-fetched to conclude that mainstream macroeconomics is a “confidence trick”.

The UK Guardian article suggests that:

The slow death of Greece was a political project from the start, with politicians accepting the prescriptions of neoliberal economics. The country has become the guinea pig for the future of a Europe ruled by German capital and Eurocrats. The economic measures were planned in Berlin and Brussels and are implemented in Athens by pliant politicians. They aim to reduce violently the standard of living of ordinary people, abolish the few remaining social safeguards and create third world working conditions …

The wholesale destruction of the weak welfare state, the massive transfer of public assets to private hands at bargain basement prices, the largest internal devaluation since the 1930s and the loss of national independence are part of the necessary re-arrangement of capitalism for a period of low growth and popular militancy. The supposed “rescue” is a test run for a new type of predatory capitalism after the failure of growth through the financial bubble.

The article documents the way in which the political parties in Greece have become captured by the European elites and implemented the neo-liberal agenda, sometimes without realising that this would “hasten their own political demise”.

The article argues that “the appointment of … Papademos … Was aimed at capitalising on the prestige of mainstream economists, and reversing the distrustful politicians”.

Further, as popular support for the fiscal austerity waned, “democracy itself became the target”. We are all familiar with the events that followed – including, the “proposal that Commissioner … be appointed to run the Greek economy”, and the fact that the two main “party leaders have signed a letter agreeing to pursue the austerity measures after the election”.

The article concludes that the “Post-civil war” divide in Greece between the left and others:

… is now coming to an end as both working people and modernisers realise that the political elite has betrayed them. For the first time, new types of political action are on the agenda. A hegemonic bloc combining the defence of the welfare state, democracy and national independence can bring together parts of the population who were historically on opposing sides but now express their indignation together.

However, I have my doubts given how in-grained the neo-liberal logic is, even among notable progressives.

Conclusion

Greece can only go forward now if it abandons the Euro. A restoration of currency-sovereignty will allow for immediate domestic-oriented growth to occur.

As I have argued in previous blogs – for example, Greece should default and exit the euro immediately

– my assessment of the real costs of such an action is that they be lower in the medium- to long-term, and the current course of action.

The increasing recognition that Greece will be in a stalled, if not contractionary state, for years to come only reinforces my assessment.

The IIF document supports my conclusion.

By the way, I don’t play Sudoku!

The next two days will be a data bonanza. Tomorrow Australian National Accounts for the December quarter comes out and Thursday the February Labour Force data will be out. A picture will emerge of how well the Australian economy is currently faring.

That is enough for today!

That is some truly really fascinating graphing there, Bill, when it comes to projected growth in Greece. In your projection, I assume you completely ignore the little insignificant global financial crisis that happened in 2008, or you somehow think that Greece would have been about the only western economy that wouldn’t have felt it at all, for some reason that you forget to mention in your article.

The austerity measures in Greece were first “implemented” (if one can call what happened implementation) in the spring of 2010, so any “Depression” before that date can hardly be blamed on fiscal austerity. In fact, the mid-2008 to mid-2010 period is a period where the various stimulus programs were implemented in the EU (the measures which were eventually bundled together in the so-called EU “2008 Economic Recovery Plan”), including in Greece.

@Andrei,

Imagine that the Depression (I now use that term for Greece) had not have occurred and the Greek economy had have continued growing at that average pace.

The following graph shows the comparison between actual real GDP growth (blue line) and projected real GDP growth (in the absence of the Depression).

I think you didn’t read everything, Bill introduces this graph explicitely stating that it is what you obtain when you take the impact of the fincancial crisis out of the picture (so when you adjust the data down accordingly, and taking austerity only as the difference between the red and blue curves). That’s when he writes:

Imagine that the Depression (I now use that term for Greece) had not have occurred and the Greek economy had have continued growing at that average pace.

And:

The following graph shows the comparison between actual real GDP growth (blue line) and projected real GDP growth (in the absence of the Depression).

Therefore you have:

The gap between the two lines is the lost real national income as a result of the Depression which has been created by the fiscal austerity.

I think you haven’t quite understood what my point was.

Bill claims in the conclusion to that section that what he calls the Greek “Depression” was “created by the fiscal austerity”, but that is factually not true – the fiscal austerity measures took effect well into 2010, so any loss of real GDP before that point in time will have had some other causes.

What’s more, he clearly is guesstimating the lost “510 billion Euros” over the entire 2008-2016 period where the two lines in his graph diverge and attributes them again to the fiscal austerity. But that’s obviously a gross misrepresentation, since the losses between 2008 and 2010 are actually attributable to other issues (e.g. the global financial crisis) and the losses between 2011 and 2016 (which might be attributable in part or in total to austerity measures) would be significantly smaller – since the divergence of the two lines would be far lower once one reintroduces the effects of the global crisis on the projected growth.

What are the odds that if the Greeks would exit the Euro they would install a neo-liberal government that would then use austerity in an attempt to correct the problem? After all, the neo-liberals seem to control the press, the universities, and the international organizations such as the OEDC. There seems to be no way out for the poor Greek people.

Dear Andrei (at 2012/03/06 at 19:20 and 2012/03/06 at 20:02)

Tristan has already made the relevant point.

But to provide some further information consider the following graph – which is taken from IMF WEO data (September 2011 database). It shows real GDP from 2000 to 2011 (the figure for Greece is overstated – the decline was in face worse than that shown – I used the unadjusted data) – for China, Greece and Australia.

China slowed marginally but used a massive fiscal intervention to redirect aggregate demand towards the domestic economy once its export growth slowed. Australia also introduced very early in the cycle a massive fiscal stimulus (about the largest as a % of GDP of any nation). Our economy slowed but didn’t go into decline. Greece failed to stimulate in 2008 when it should have and started to decline. That decline was accelerated once the pro-cyclical fiscal austerity was imposed.

So while the projection graph in the blog text is just a thought experiment, it is clear that the Greek economy could have kept growing had they stimulated enough and had control of their own currency. The assumption used to make the projection in the graph (average growth between 1994 and 2007) amounted to a slowdown anyway in the real GDP growth on the performance of the economy in the immediate years before the crisis when they grew by 5.17 per cent in 2006 and 4.28 per cent in 2007. So not unlike what happened in China and Australia.

Some countries did avoid the worst of the downturn by early and sizeable fiscal interventions.

best wishes

bill

Andrei says:

“Bill claims in the conclusion to that section that what he calls the Greek “Depression” was “created by the fiscal austerity”, but that is factually not true – the fiscal austerity measures took effect well into 2010, so any loss of real GDP before that point in time will have had some other causes.”

.

The Economist article “Worse and worse” (5 March 2012) contains a graph showing how Greek manufacturing output fared since 1999. The graph is lifted from a brief overview of Greek economy, done by Markit. It measures what they call the Purchasing Managers’ Index. [See Note, below.]

.

We notice Greece has kept a steady pace of small growth all the way until the 2008 crisis hits, when manufacturing plummets. We can debate which factors contributed to that plunge and I would agree that these factors were mostly foreign, as you say. But the important message from the graph is that manufacturing rebounded within a very short period of time and even registered a tiny bit of growth in the middle of 2009!

.

True decline starts when, by 2009, the austerity measures are announced (and scenes from protests start filling out TV screens) (Where’s that remote? There’s a ‘Friends’ re-run in the next channel).

Greece then enters a period of “50 consecutive months of decline” and still comes to score a “record” decline in February 2012. That record will not last for long. As soon as the imminent “help” by the IMF is announced along with a package of austerity measures, confidence plummeted in Greece. The private sector saw the writing on the wall.

.

There is an evident, strong chronological correlation between the announcement of the austerity measures and Greece’s real economy decline. This may not imply causation, but the arguments for what austerity would do to Greece and the whole systemic problem of the Eurozone have already been put forth by Bill Mitchell (and many others). Your dispute about the current situation in Greek being little more than the world financial crisis tsunami-ing the Greek shores is not accurate. That’s the point.

.

The austerity measures were “necessary” only in so far as Greece was (and still is) practically unable to net-deficit spend and conduct an expansionary fiscal policy. Being inside the Eurozone, the Greek government’s discretionary fiscal authority is virtually limited to collecting taxes. It’s like a surgery where only incisions are allowed. Without the austerity measures, there is no earthy reason to believe that the country would have faced the same collapse. (If the portion of GDP that now goes out to pay off interest on the debt would have being directed instead on the local economy, things simply cannot have turned out “the same”!)

.

This is the crux of Bill’s argument: The systemic untenability of the Euro contraption itself, at least the way it has been set up till now.

.

Greece has “chosen” to seek help from the Euro bosses the same way a small business owner “chooses” to seek help from the local gangsters, on account of his unsustainable debts, debts which were created by those gangsters in the first place! In the end, the small business owner is forced by events (“through his own free will” and often begging for it) to hand over to the local gangsters the operation, the financial control and eventually the ownership of his business.

.

Cheers,

Vassilis Serafimakis

—

Note: The copyrighted term Purchasing Managers’ Index is “a composite indicator designed to provide a single-figure snapshot of the performance of the manufacturing economy”. According to its owner, “financial information services” company Markit, PMI is based on “five individual indexes with the following weights: New Orders – 0.3, Output – 0.25, Employment – 0.2, Suppliers’ Delivery Times – 0.15, Stock of Items Purchased – 0.1, with the Delivery Times Index inverted so that it moves in a comparable direction.”

Economist article here:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2012/03/euro-crisis

Markit website here:

http://www.markit.com/en/

Dear Bill

Since you threw some German quotes, let me use a German proverb: Besser ein Ende mit Schrecken als ein Schrecken ohne Ende = Better an end with horror than a horror without end. If the Greeks end their experiment with the euro, they’ll have a very stormy year, but after that it should be smoother sailing. If they’ll keep the euro, they’ll have many bad years ahead of them.

Regards. James

Per GLH’s point, if Greece leaves the Euro, yet continues with a neoliberal government attempting to honor all debts by a policy of wage deflation, then leaving the Euro doesn’t make much of a difference. Greece has to BOTH leave the Euro AND get rid of neoliberal policies for there to be any appreciable improvement, and from my vantage point, while the former may be forced, the politics which will bring about the latter are nowhere to be seen on the Greek political horizon.

If Greece defaults, the puppet rentiers currently installed will want no part of it. They’ve already got their money out – just their tailored suits and resumes to pack and exit stage left. It would be cool if the same MMT contingent that went to Italy were invited to Greece to advise on its economic recovery.

This is an interesting article by Dean Baker in Al Jazeera English. It makes all the MMT points about the recovery of the Iceland economy, because of its control of its own currency, in contrast to the European periphery. Of course the article begins by mocking what Dean considers a totally crazy idea. The Icelanders are apparently considering adopting the Canadian Dollar as their official currency.

http://www.cepr.net/index.php/op-eds-&-columns/op-eds-&-columns/the-iceland-follies-loony-currency-schemes

I sometimes think Dean Baker and his colleague would fit right in to the MMT fold with just a couple of exceptions. Dean is fairly influential and is on American TV frequently.

@SteveK9: I think MMT would agree that Iceland adopting the Cdn dollar is a bad idea, even a ‘crazy’ one. To me, Dean’s failing is his belief that trade surpluses are the only thing that can bring economic growth to a country. He doesn’t comprehend that a government with its own currency can spend all needed currency into existence and does not have to depend on inflows of foreign currency.

That is too simplistic Bill. Surely even you will agree that the way a real world economy behaves under the influence of exogenous factors like the global financial crisis can vary, and so can its response to internal stimulus packages, in ways that are not determined solely by the size of the stimulus or their implementation timeframe. In other words, why assume Greece would have behaved exactly like Australia and China?

We have already seen that there are other factors at play, like the specific composition of the GDP and the economic productivity (see: Greece’s reliance on tourism and its weak industrial production), the influence of the export sector and its composition (see how important sectors, like Australia’s mining sector or Greece’s shipping sector behaved respectively in the various phases of the crisis), the main trade partners (see how much more important China in particular and Asia in general is for Australia, and how much more important the EU is for Greece) and so on and so forth. In other words, assuming that Greece stimulating its economy in the same way as Australia did would have produced the same results in real GDP growth is pretty… unfounded, to say the least.

Not only that, but we also have clear proof that this would have not been necessarily the case – you of course selected China and Australia as comparisons points, but we have others: for instance, both the United States and South Korea had stimulus packages that were larger than Australia’s (in GDP percentage terms, per OECD comparison studies) and implemented in roughly the same timeframe: the US as we all know still had a clear real GDP slump in 2009, while South Korea saw essentially no GDP growth in the same year. We also have reference points far closer to Greece than all of the above, like for instance Germany and Spain – while neither had stimulus packages that were quite as high as Australia’s in GDP terms, they were certainly comparable and early applied, yet Germany’s GDP still decreased significantly in 2009, as did Spain’s. Now, of course, the exact composition of the stimulus package plays a role as well, and there was an undeniable difference in terms of the balance between direct spending and tax cuts (with Australia being significantly more on the side of direct spending than some of the other countries mentioned), but this just goes to further illustrate how pointless it is to think that the effects of stimulus in one economy are directly applicable to another, since it depends on so many more factors, including some structural ones that can’t be quickly changed by fiat.

So, it is quite clear that in the end-of-2008, 2009 and beginning-of-2010 period, there was no guarantee that a stimulus program – even one as big as Australia’s – would have ensured Greece’s GDP growth would have been anywhere near what your optimistic graphing implies. In fact, as we have seen from examples other than China and Australia, the likelihood of a GDP slump or stagnation was at the very least equal to the possibility of slower growth.

Not only that, but we still have the problem of the basic distortion: you blame Greece’s “Depression” entirely on fiscal austerity, and quantify the austerity effects at 510 billion, counting essentially every euro difference between 2008 and 2016 on your graphs as being caused by it. That is demonstrably wrong – fiscal austerity as understood by the mainstream discussion of the topic (i.e. spending cuts) really started in Greece at the beginning of 2010, so anything before that can only be blamed on other factors, including if you must, lack of increased spending, altough pretty much nobody would sort that under the “fiscal austerity” tag. That\’s quite the different claim than the one you make in your post.

IMO, if you wanted to hold yourself to the same standard that you hold the various mainstream economists and institutions you like cite and reprimand for being misleading with economics and statistics in order to manipulate public opion (which they undoubtedly often are doing), you should have watered down your claims – your thought experiment would have been much more persuasive if you had tried to make more realistic assumptions about the GDP slump that Greece would have experienced in the first years of the crisis (even with a stimulus package), make the lines diverge much less (if we want to accept your claim that fiscal austerity is to 100% percent responsible for the continuing slump from 2010 on) and so arrive at a far lower and therefore slightly more believable figure for the losses.

Andrei said:

“That is too simplistic Bill. Surely even you will agree that the way a real world economy behaves under the influence of exogenous factors like the global financial crisis can vary, and so can its response to internal stimulus packages, in ways that are not determined solely by the size of the stimulus or their implementation timeframe. In other words, why assume Greece would have behaved exactly like Australia and China?”

Isn’t it obvious that such comparisons are made on the premise of “ceteris paribus” (“all other things being equal”) ?

How else would you suggest one should be making comparisons? We have a real situation A and we change from it only factor k. We chart course A’ with, instead, factor k’, leaving everything else unchanged. and compare. Such an exercise does not mean that the course would’ve necessarily been A’ but it shows the effect of moving from k to k’, in approximation.

“Surely even you…”

You think Bill Mitchell is biased? Or perhaps in the pay of the Gang of the Drachma?

The “Gang” appellation is the latest smear directed by Greek pro-Euro commentators and politicians against anyone presenting unorthodox views abt our currency. It’s a typically totalitarian tactic, which aims to denote the opposition as small and insignificant (“they are only a gang, a handful”) and as having sinister objectives (“gangsters”).

Recall the Gang of Four. (The Chinese; not the musical act.)

I suggest that if the comparisons should have any meaning, they have to use underlying assumptions that are within the realm of at least possibility if not reality, and that one has to ensure that the variables one ignores aren’t so fundamentally important as to completely change the outcome you want to investigate.

Assuming that Greece would behave like Australia (let alone China) ignores such fundamental differences between the economies that it makes Bill’s comparison more of an exercise in creative fiction, especially in the context of assigning blame (or calculating potential damages!) and doubly so because neither Australia nor China are the only real world examples that we can a posteriori point to.

I have little interest in discussing Bill’s biases, let alone your totalitarian fears since such discussions are generally unfruitful and veer quickly into personal attacks, but I would say this: sometimes, like for instance with this graph, Bill tends to get a bit too much on the side of trying to manipulate through fictional statistics, and I see no problem on calling him on it – just like he calls out (and rightly so) various say neo-liberal circles when he sees obvious and fabricated propaganda coming from them.

If I have some time, I should not forget to address a few points in your other reply to me, since there is definately some need to clarify and or nuance.

Dear Andrei (at 2012/03/07 at 21:46)

You noted:

The stimulus size was not the important point but rather the size relative to the output gap. Australia’s was one of the largest in that respect and we also benefitted from the Chinese stimulus more than other nations.

Further, the US federal stimulus was compromised because all the state and local governments were contracting at the same time.

But the general point which you seek to deny is that whenever the austerity formally started in Greece the Greek government could have, if it had its own currency, stimulated domestic demand with appropriately scaled fiscal interventions (to meet the output gap) and avoided the downturn altogether. There is no inevitability that when the rest of the world enters a downturn a specific country has to follow suit.

The examples of China and Australia demonstrate that.

In general, there is no crisis deep enough that fiscal policy interventions cannot attenuate. That was the point of the experiment rather than to manipulate opinion with fabricated statistics.

If you disagree with the proposition that a currency-issuing government can always maximise the potential of domestic resources (even though that potential might generate very low GDP output in a relative sense for resource-poor nations) then you should say that. Because that is what is underlying your criticism.

best wishes

bill

Andrei: When Bill extends the growth line for Greece, rather than say tacking on the growth line for China or Australia – he is thereby making the underlying assumption that Greece will behave like Greece, not China or Australia. Is not Greece behaving like Greece “within the realm of at least possibility if not reality”?

Being a clear-thinking economist, Bill’s deeper assumption is that the Greek economy will behave like an economy, something that China and Australia also have, and something he has been theorizing about for a while. This is the only way he is assuming Greece will behave like China or Australia. And his theory assumes & indicates that government spending is just as good as any other spending, and will have roughly the same results. This logical assumption tends to explain empirical data in any country quite well.

Saying that impossible/unlikely underlying assumptions have been made & fundamentally important variables ignored is not the same thing as pointing such assumptions & variables out, even if one who says this thinks he has.

Bill, you are the one who brought up the stimulus size as a percentage of the GDP, remember? Your words: “Australia also introduced very early in the cycle a massive fiscal stimulus (about the largest as a % of GDP of any nation). Our economy slowed but didn’t go into decline.” You seem to have thought, a few messages ago, that the size of the Australian stimulus was important, and didn’t mention anything about the relationship to the output gap.But OK, let’s switch gears in mid-discussion, and talk about its size relative to the output gap, with Germany as an counter-example this time: the output gap in 2009 of Germany (per IWF estimates) was smaller as a percentage of the GDP than the one of Australia. Meaning that even thought Germany had a smaller stimulus package as a percentage of the total GDP, it was just as large or largerer than Australia’s in terms of its size relative to the output gap. Yet Germany went through a clear and steep GDP decline in 2009.

No matter which criteria you want to look at, there are plenty of counterexamples to the premise that a stimulus package by itself would have insured GDP growth in Greece at the beginning of the crisis. I doubt anybody would disagree that a large stimulus package might have made that decline smaller, or that such a stimulus could have provoked a return to growth sooner, but there is no reason to believe that there wouldn’t have been a slump or stagnation in the 2009-2010 timeframe. Which is why both your graph and your damage estimates are so questionable.

As an aside, one cannot suppress a bit of a grin whenever one hears macroeconomists speaking about “the” output gap – which one, one always wants to ask, given the often disagreeing estimates of the output gap that various institutions use and abuse, let alone the theoretical discussion about how one goes about calculating it at all.

The examples of the US, South Korea, UK, Germany, Spain or France demonstrate the exact opposite. Which was the point all along – while it is true that a worldwide crisis doesn’t inevitably cause a specific country to experience temporary decline or stagnation, it also doesn’t mean that that country can necessarily avoid it. So I think it is still up to you to explain why you think that Greece would have necessarily followed the general path of China or Australia, given the realities of the greek economic structure and composition of its main trade partners. Real world experience shows us that not-too-dissimilar stimulus packages to the one Australia implemented were not sufficient for other countries to avoid decline or stagnation in the first stages of the crisis, which should tell us that other factors besides the stimulus must have played a role as well – I am guessing you accept that, since now you mention that Australia profited from the chinese development more than other nations.

To nitpick, I am not sure I follow your logic on the topic of “whenever the austerity formally started […] the government could have […] stimulated domestic demand”. Government spending in order to stimulate demand is not part of any austerity definition I am personally familiar with. Maybe you meant “whenever the crisis formally started”? That makes no sense to me either, we all know and agree (I hope) about when it started, no formal definition needed.

That aside, let’s get back to the Greece question, and pretend that it would have been possible for Greece to create a stimulus package similar to the one Australia implemented – to be honest, I actually tend to disagree that the Greek government would have been able to implement it at all. How would they? Tax reductions? In a economy where tax evasion is so widespread, the effect on demand would have been more than modest, to say the least. Direct spending? Sounds good, but the fact of the matter is that Greece is hanging way behind in the absorbtion of the regular “stimulus package” it receives through the EU structural cohesion funds each year: Greece has billions upon billions waiting to be invested, and they can’t manage to channel them in their economy, even in the midst of such a deep crisis.

You could blame EU bureocracy for that or maybe staff shortages because of the austerity cuts (the irony – if it were true), but both variants can’t fully explain the lag. For one, even very new members like Romania and Bulgaria, let alone the countries from the 2004 wave, are in some or many respects better than Greece at absorbing structural funds, despite the fact that Greece has had far more experience dealing with EU funding – so others can and do deal with the EU bureocracy just fine. On top of that, the low absorption rate with significant delays is a historical reality in Greece that goes back to the 90s and even further, so it can’t just be an artefact of the current government restructuring either. Some may point to the increased difficulty in the last few years of securing co-funding for the national resource side of the EU project investments, and I’ll grant you that this would not be (as) necessary if Greece would have its sovereign fiat currency, but again, the historical data does not lie (much): even in times of cheap and abundant financing possibilities, even in times of a sovereign currency, the Greek government had major problems investing the EU funds, so that can’t be the full explanation either.

Also, I take exception to you turning the discussion around, as if the projections in your article were based on the idea that Greece had its own currency – they weren’t, you specifically claimed it was the fiscal austerity that was causing the damages and the slump, and implying that just the lack of fiscal austerity would have created the constant growth projection you used. Because if you had meant that your growth projections were made with the premise that Greece has its own sovereign currency, your graph has much, much bigger problems than just talking about details like when the fiscal austerity started, or how much the GDP would have slumped in 2009 with which stimulus package.

It has fundamental problems because Greece had no drachma at the beginning of the global crisis and it would not have been able to magick it into existence overnight in 2009, not without at least some short and mid-term repercussions. The reintroduction of the drachma would have had to involve a hard default because Greece couldn’t both quickly devaluate their new currency and at the same time service the existing debt in Euros – with all the consequences that would have entailed in terms of procuring foreign currency to purchase the essential goods (like oil) that Greece can’t avoid importing no matter which local currency it has. It also would have meant a period of heavy turbulences in its internal economy – as we have seen with other defaults in recent history, even if they end up leading to a recovery, the currency change cost, inflation and uncertainty still mean a couple of years of sudden real GDP decline and increased unemployment, quite possibly even steeper than what happened in reality. Again, a fact which your graph completely ignores.

Maybe your growth projection was of an idealised Greece that never joined the EMU? This would be a charitable reading, but even so, it still has basic honesty problems – you can’t completely de-couple the growth Greece experienced between 1994 and 2008 from it joing the Eurozone. The greek economy grew at a rapid pace just for a couple of years before and in the years after joining the Euro, and causation is clear – the greek growth was undeniably due in part to the country joining the Euro, both due to the positive aspects of the monetary union (like more fluid trade & tourism) and its less positive aspects (the more or less sudden access to cheap credit).

If you want to claim that your graph represents a sovereign currency Greece that never joined the EMU, then you must eliminate the effects the Euro itself had on Greece’s growth. Which of course is really difficult to do and in the end, much like your original misleading graph, just sterile wankonomics because it reduces complex developments in lets-massage-numbers and paint-a-graph morsels.

But, on the other hand, why not, let’s indulge ourselves: we have historical data on how Greece has been performing with their own currency, so let’s choose 1980 to 1999 as a reference time frame: we see an average real GDP growth rate of just 1.3% (a far cry from your proposed 3.6%) and only so high because we include the higher growth between 1997 and 1999, which was fueled by the reforms Greece implemented in order to meet the Euro convergence criteria combined with the expectations of Greece getting in the EMU with just a small delay – without the tail end period, the average is even lower than 1%! If we wanted to be pesimists, we could extrapolate Greece’s growth from 2000 onwards (the Euro inflexion point) using this 1.3% drachma-based growth rate and so end up with really dire numbers. I won’t do that, after all one cannot reasonably claim that all the growth Greece experienced as it prepared to join the Euro and then throughout the 00s until the crisis struck was only due to the Euro. We know a part of it was but there were also internal reforms and generally somewhat better government, so let’s make it simple and just average Greece’s growth from 1980 to 2008, and call it a day – we reintroduce some of the effects of the less-than-rosy drachmaconomy of the first two decades back in the picture but we don’t eliminate completely the endogenous growth that Greece experienced in the last decade either. So let’s re-do your extrapolation using the same WEO data sources and estimates that you used, but applying for Drachma-Greece from the euro cut-off date a long-term growth rate of 2,16% (the average between 1980 and 2008) and comparing it with the actual development of Euro-Greece.

Graph Euro-Greece vs. Drachma-Greece

We see that in this scenario, while Greece may have stood right now with the drachma better than with the Euro, the lost GDP output in the latter years would have been more than compensated by the increased GDP output in the former, making the “damages” averaged over this period inexistent. And, let’s recall, this is a scenario where we assume that Drachma-Greece would have not felt any effects of the financial crisis – if they had, and had experienced stagnation or decline (like many other sovereign currency countries did) instead of the 2% constant growth we guesstimated, then the equation would be even more balanced in the favour of the Euro. I guess one could say that there was the chance that a drachma-based Greece would have avoided the more difficult and painful wage and pension readjustments, doing them longer or shorter term as needed through inflation instead of the austerity-introduced hard wage cuts, which is undoubtedly a plus point, but other than that, if we want to measure gains or losses purely in terms of GDP (like you originally did), the Drachma-Greece does not stand better than the Euro-Greece.

You don’t need to dig deep in the underlying currents of my criticism, since my criticism is both quite clear (I think) and quite specific: your timeline about the fiscal austerity in Greece is wrong, your assumption about a constant 3.5+% real GDP growth during the global crisis is unfounded and therefore your calculation of the 510 billion in damages caused about the fiscal austerity is grossly overestimated. That’s all.