Regular readers will know that I hate the term NAIRU - or Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment - which…

The politicians in Europe and the UK are deliberately sabotaging their economies

Eurostat published their latest National Account estimates for the Eurozone on Wednesday (February 15, 2012) – Flash estimate for the fourth quarter of 2011 – which allows us to complete the picture for the 2011 calendar year. Overall, the results are appalling. Many nations are now double dipping and even the European powerhouse, Germany contracted last quarter. Over the Channel, the British economy also contracted in the 4th quarter 2011. None of this should come as any surprise. An economy cannot grow when the private sector is deleveraging and is in constant fear of unemployment and the public sector deliberately refuses to step in and provide fiscal support. It is even worse when the government further undermines the capacity of the private sector to spend (by harsh cuts in pensions etc) and cuts its own net spending into the bargain. As one commentator noted yesterday “it makes no sense to drive an economy into recession where it stops people from working and thus paying more taxes” if the goal is to reduce budget deficits. The political leadership in Europe and the UK is deliberately sabotaging their economies. The same mentality is gathering pace in the US. Spare us!

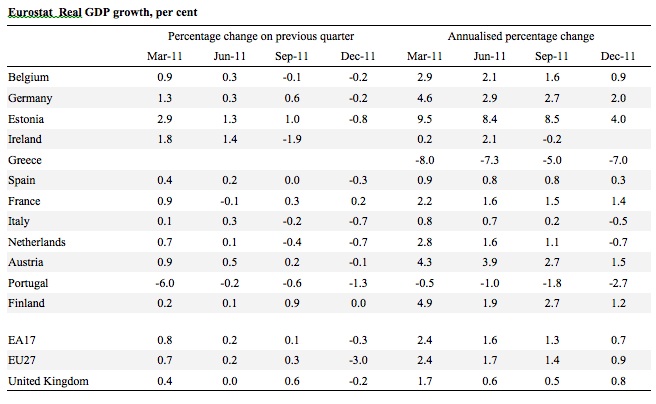

The following table is constructed using the Eurostat flash estimates of real GDP growth as at the December quarter 2011 (released February 15, 2012). The trend is relatively uniform across the EMU and for the UK as fiscal austerity imposes a significant constraint on aggregate demand.

While no quarterly change data was published for Greece, the annualised growth (last four columns) paint a very grim picture.

One might conclude that while the World avoided a repeat of the Great Depression as a result of the fiscal stimulus packages (and low interest rates) that governments around the world managed to implement before the deficit terrorists started chanting about austerity, Greece did not.

Since 2009, the Greek economy has shrunk by around 8 per cent in real terms with worse yet to come. In real terms, GDP is now around the size it was in 2006.

The Table shows that many EMU nations are now back in recession (2 successive quarters of negative GDP growth). The list includes Belgium, probably Ireland (no data was released the December quarter yet), probably Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Portugal.

Other EMU nations are heading that way – for example Estonia, Germany and Austria are now contracting.

Overall, the broader EU contracted very sharply in the December quarter (-3% in real terms) and the Euro area also contracted.

On the same day, the UK Office of National Statistics released the latest – Labour Market Statistics – for February 2011 which indicates that:

The employment rate for those aged from 16 to 64 was 70.3 per cent, up 0.1 on the quarter … The unemployment rate was 8.4 per cent of the economically active population, up 0.1 on the quarter … The unemployment rate has not been higher since 1995. The inactivity rate for those aged from 16 to 64 was 23.1 per cent, down 0.2 on the quarter.

One might conclude that this is not all bad news. As the UK Guardian editorial (February 16, 2012) – Employment and the euro crisis: bringing it all back home – said:

For the day after inflation was revealed to be easing off fast, there were – on the face of it – signs of employment stabilising, too. The total tally of jobs inched up, inactivity fell, and – even as benefits policy cajoles disabled people and carers into signing on as jobseekers – the dole queue lengthened relatively modestly. This is, to be sure, stabilisation of a dismal sort.

But a closer look at the data suggests a different interpretation consistent with the view that austerity (which is yet to fully impact) is damaging job prospects in the UK.

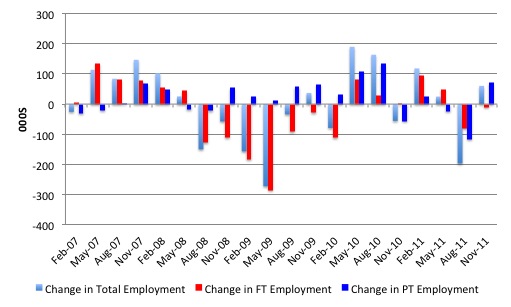

The following graph is produced from ONS data – EMP01: Full-time, part-time and temporary workers – and shows the changes (in thousands) since December 2007 in the major employment categories (full-time, part-time and total).

You can see that in the last two quarters, full-time employment growth has been negative and all gains in employment in the current period are attributed to part-time work.

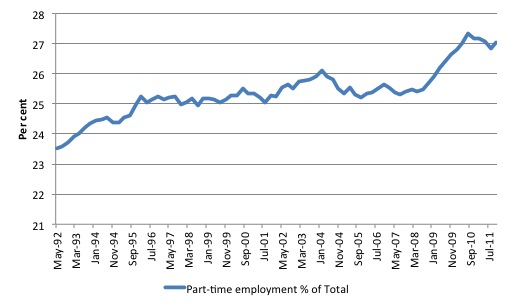

The next graph provides a longer view of the labour market and depicts the ratio of part-time to total employment (in percent) since 1992. The graph shows that this ratio rose during the recession in the early 1990s and then was relatively stable at the higher level. During the current recession, the ratio has accelerated upwards.

This is a common pattern across many countries. During recessions there is usually a marked switch from full-time work to part-time work for both males and females resulting in a greater proportion of workers in short-duration and unstable jobs.

During recessions and subsequent recovery, the ratio typically rises rapidly before stabilising at the higher level with the underlying trend towards increased part-time work then reasserting itself.

That pattern is clearly evident in the UK.

UK Guardian editorial puts an appropriate degree of gravitas to the data release:

Employment blackspots such as the north-east continue to darken; twice as many as before the recession now work part-time for want of a full-time post; and there is still no hope in sight for youngsters struggling to find a first footing in work.

Spatial disparities – where some areas have relatively low unemployment and good employment growth while other areas represent the proverbial train wreck – also tend to widen during a recession and its aftermath.

Taken together, the EU data and the British labour force data accentuate what was always going to happen – Austerity begets austerity – despite the denials of the political leaders and their chorus of mainstream economists.

Every day, the austerity merchants and their chorus attempt to cast doubt in the public minds about budget deficits – that they are harmful and the private sector is better off without them.

What the public is not told is that budget deficits drive growth but also drive private business profits. This becomes especially so when the other determinants of profits vanish.

One of the reasons the public debate is so vacuous and that scoundrels can hold fort is that the public do not know how to reason in macroeconomics terms. They are continually being led to think in a micro way and are not warned that such thinking leads to erroneous conclusions when we transcend to the macro level.

To help make the transition into macroeconomic reasoning consider the following graphs. They use US data for convenience (good data availability) but the relationships depicted can be found in most countries where data is available.

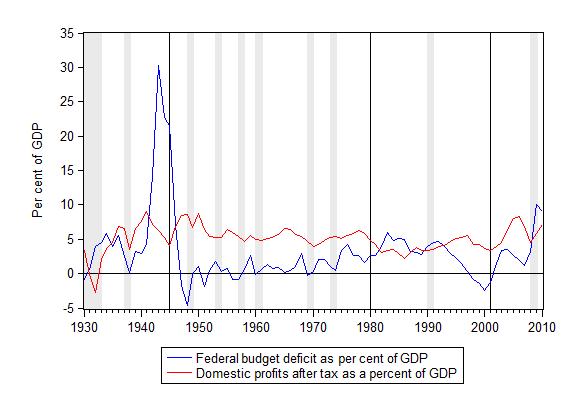

The following graph shows the US federal budget deficit as a percentage of GDP (data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis) and the US Domestic Company profits after tax from 1930 to 2010. The shaded areas represent the nearest annual spans of recession as estimated by the NBER Business Cycle Analysis.

Similar graphs would be constructed for most nations at present.

The interpretation of the relationship is that when the budget deficit line is below the domestic profits line, the other determinants of profits are playing a positive role. But in 2009 and 2010 the US federal budget deficit was more than 100 per cent of domestic profits which means the other determinants were netting to a negative number.

There have only been three times in the history shown when this has been the case – the Great Depression and World War 2 years, the Reagan years (after a very deep double-dip recession) and during the current recession.

If the US government had have invoked austerity measures along the European and/or UK lines, then profits would have been much lower (maybe negative) given that the other determinants have been largely missing in action.

The graph provides a very powerful reminder that budget deficits are a crucial driver of business profits, which in turn, helps (in a capitalist system) to drive employment. The downturn would have been much worse in the US than it actually was (and it was bad enough) had the US government followed the advice of many economists and resisted expanding its budget deficit.

The following graph shows the proportion of Company profits accounted for by the US Federal budget deficit. From 1950 to 2007, this proportion averaged 43.3per cent. If we took out the Reagan years then this average drops to 19.1 per cent. In 2008-2010, the average proportion was 122.7 per cent. The current period is quite exceptional in the historical span shown.

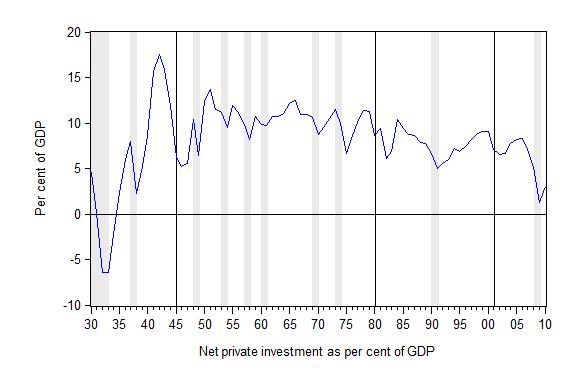

You might ask what was happening with the other major driver of corporate profits – private investment spending. The following graph shows US net investment as a per cent of GDP from 1930 to 2010. Over the entire sample (1930 to 2010) this ratio averaged 8.1 per cent of GDP.

In 2009 it was 1.3 per cent of GDP and only 3 per cent in 2010. The interpretation is that the main private driver of capitalist profits (private capital formation) was largely missing in action during the recession and had the US federal government not introduced the stimulus measures and expanded its budget deficit significantly then domestic corporate profits would have plunged more than they did.

What would have happened if the fiscal stimulus had have been more targetted to direct public sector job creation? The conclusion with respect to profits would not be much different. The major difference would have been that unemployment would not have risen by as much.

How might we understand the economics underlying the movements shown in these graphs?

I provided the theoretical development to understand these relationships in this blog – Why budget deficits drive private profit.

That blog is about macroeconomic reasoning. To demonstrate what I mean by that ask yourself the question: what determines the level of profits in the economy?

Most people will start by considering a business firm and articulating the revenues they receive and the costs they incur in doing so. For an individual firm, the difference between the two is the profits it receives (or loss).

It is also clear that for most firms, wages represent the most significant cost. Accordingly, it is tempting to conclude that the economy can increase profits if the individual firms can contain wage costs.

If business investment is sluggish and constraining economic growth, one might be tempted to extend this logic and advocate cutting money wages to reduce costs overall so that overall profits will rise and spur growth in investment.

Once you start thinking in these terms – from specific to general or from micro to macro – you cease to be able to explain aggregate profits. The graphs presented above will make no sense to you.

The question we are seeking to answer is not how much profit an individual firm makes in any period but

what determines the total volume of profits in a monetary economy in any given period. Marx focused on this question as did Polish economist Michal Kalecki among others.

It is a central concern of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and once we understand the answer we gain an appreciation of why budget deficits are usually essential.

The reason the earlier intuition about a firm’s profits would not be helpful in answering our aggregate question relates to what happens when a change at the individual level is applied to the general level.

If wages are cut at the individual firm level, then other things equal, the firm will likely be more competitive and be able to gain a larger market share and increase its overall profits. We can assume that the firm’s revenue will not fall sharply when its costs are reduced.

But we cannot sustain the other things equal assumption (revenue constant in this case) when we apply the wage cut at the aggregate level. It is a fallacy of composition to do so.

When wages are cut across the economy, costs fall for all firms but it is likely that revenues will also decline because wages typically drive consumption.

It is highly likely that overall profits will fall in this generalised situation.

This sort of reasoning forms the basis of Kalecki’s general model of profit determination (sometimes called the Kalecki Equation).

Kalecki initially used a very simple two-sector model (households and firms) to demonstrate that under simplifying assumptions about workers’ saving, economy-wide (gross) profits (P) is equal to the amount that capitalists spend on their own consumption plus gross investment.

Kalecki said that capitalists “get what they spend”.

I won’t repeat the derivation of that model – see Why budget deficits drive private profit.

So he could now analyse how the major components of aggregate demand (expenditure) impacted on corporate profits at the aggregate level.

He began with the familiar national income accounting identity (that is, it must hold as a matter of accounting:.

Total national income or GDP (Y) is given as:

Y = C + I + G + NX

where G is government spending and NX is net exports (total exports minus total imports). C is the aggregate of capitalists’ consumption (Cp) and workers’ consumption, which is total worker income post tax (Vn) minus workers’ saving (Sw). We assume no depreciation of capital.

So we could write this model as:

Y = Cp + (Vn – Sw) + I + G + NX

to recognise the different sources of total consumption.

Total income claimants on national income (Y) are:

Y = Pn + Vn + T

where P and V are as before (profits and total wages and salaries) but the subscript n denotes these flows are net of taxes paid, and T is total taxes.

This equation thus tells us about the distribution of national income between the government (who takes out taxes), workers (wages) and capitalists (profits).

We can integrate these two perspectives (or views) of GDP by setting the expenditure components of total income equal to the claims on total income to get:

Cp + (Vn – Sw) + I + G + NX = Pn + Vn + T

You will note that Gross Profits after tax (Pn) is in this equation and we can isolate it on the left-hand side (by re-arranging terms) as follows:

Pn = I + (G – T) + NX + Cp + Vn – Sw – Vn

So:

Pn = I + (G – T) + NX + Cp – Sw

which says in English, that gross profits after tax (Pn) equals gross investment (I), plus the budget deficit (G – T), plus the export surplus (NX), plus capitalists’ consumption (Cp) minus workers’ saving (Sw).

So gross profits after tax in the economy will be higher:

1. The higher is gross investment (I).

2. The larger the budget deficit (G – T).

3. The higher is capitalists’ consumption (Cp).

4. The lower is workers’ saving (Sw).

This model provides an array of useful insights into the dynamics of profits in the economy and how the external and government sectors impact.

There are many interesting distributional complexities that emerge which help us bring together microeconomic insights into a consistency with the macro constraints that this model demonstrates hold for the economy as a whole.

For example, when there are positive net exports and/or budget deficits, then gross net profits (Pn) will rise higher than the level that would be generated by gross investment and capitalist consumption.

When workers increase their saving, gross profits fall because less of the workers’ income is coming back to the firms as consumption spending. When, in Kalecki’s words – the workers spend what they get – that is, in his simple two-sector model workers are assumed not to save at all (Sw = 0), then the capitalist profits are maximised from this source (other things equal).

Also an individual domestic capitalist may be able to increase their net exports and will then be able to glean extra profits “at the expense of their foreign rivals”.

Kalecki said (in his 1965 book noted above, page 51):

It is from this point of view that the fight for foreign markets may be viewed.

The model also helps us understand the evolution of the data shown in the above graphs.

Budget deficit generates profits via their impact on national income. The budget deficit means that the private sector is receiving more flows from the government than it is returning via taxes.

Budget deficits provided an increased capacity for capitalists to realise their production because they expand the economy.

Kalecki said that budget deficits allow the capitalists to make profits (net exports constant) over and above what their own spending will generate.

The converse is also true – budget surpluses undermine private profits because firms revenue falls (if government spending is cut) and/or their costs rise (if taxes go up)

When the government runs a surplus it reduces profits via its squeeze on aggregate income.

This insight alone is why the business should be opposing fiscal austerity moves by various governments.

It doesn’t make any sense, for the business lobby groups to be calling for cuts in the budget deficits.

The only time that a rising budget deficit will not add to profits (in real terms) is if there is full capacity and the rising deficits push nominal aggregate demand beyond the real capacity of the economy to increase output and real income.

The fact that the business groups often lead the charge against budget deficits reflects the triumph of ideology over good judgement and the triumph of ignorance over understanding.

Conclusion

I am giving a presentation this afternoon (that is, Thursday afternoon New York time) at Bard College (where the Levy Institute of Economics is located) entitled “why Italy should meet the Eurozone”. I’m going to make the obvious points that a nation cannot grow in normal circumstances without some support from budget deficits. At present, given the state of private spending and a huge stockpiles of private debt outstanding, that fiscal support has to be very low in relative and historical terms.

The political leadership of the Eurozone are clearly intent on denying the nation access to this fiscal support. The latest Eurostat data is a stark testimony of what happens when the nation is choked by deficient aggregate demand. Fiscal austerity is another of the failed doctrines that has emerged from mainstream macroeconomics.

There can be no growth when both the private and public sectors are refusing to fuel the growth appropriate spending choices.

The UK Guardian article by Simon Jenkins (February 14, 2012) – Austerity fails, yet we’re too shy to think outside the box – provided some sobering commentary to finish this blog on:

It makes no sense to drive an economy into recession where it stops people from working and thus paying more taxes. Growth starts not with bank investment but with demand. It starts with more money flowing down the high street. Here the curse is not Weimar but a bank-obsessed Treasury, fighting war with antique weapons such as quantitative easing that disintegrate in their hands. They can bring themselves to print money for banks, but not for ordinary people – through scrappage schemes, vouchers, corporate job-creation projects and other such off-budget stimuluses tried abroad. These methods need have no more impact on budgetary austerity than does money given to banks.

The failure to take economic management beyond the diktats of austerity has become the great intellectual treason of today. For three years it has trapped governments, economists, bankers and media in a collective miasma of panic about inflation. Thousands of citizens across Europe are having their lives ruined and their children’s prospects blighted because a financial elite, once burned, is too shy to think out of its box. It refuses to stimulate demand merely because that is not the done thing to do.

More journalists should follow this lead and start attacking the basis of this neo-liberal assault on decency.

The mainstream economists will laugh and make all sorts of rote-learned but empirically bereft accusations. Ignore them – they had their day in the sun – and in failing to see the crisis coming – they lost their right to a voice in this debate.

Saturday Quiz

The regular Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow. I might make it so hard that the demoralising effect will mean that readers won’t want to do it any more and then I won’t have to prepare it. (-:

And while you are doing the Quiz I will be flying long distances! I think I would rather be doing the Quiz.

That is enough for today!

I think there’s a little more going on here than you’re aware of. The banks create money when they pretend to lend it. Few understand that and all would no doubt be enraged if they understood. The banks have got away with this for centuries as they’ve kept quiet about it and belittled any who tried to bring the practice into the light. They obviously want to keep getting away with it but this, though, is the information age so it represents the greatest threat they’ve ever faced. What’s their tried and true tactic? Austerity. If people are scrabbling for the next meal thery won’t have time to be considering how to bring down the banks. Hence, austerity. It’s actually a last-ditch stand by the banks, a scorched-earth policy. If they must surrender then they’re making damn sure there’s precious little left to reign over. It’s working, too.

“More journalists should follow this lead and start attacking the basis of this neo-liberal assault on decency.”

Interestingly even the Telegraph is starting to join the chorus here in the UK. Jeremy Warner’s piece is almost congratulatory about the strength of the UK automatic stabilisers.

He only reverts to type near the end:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/jeremy-warner/9085051/Britain-out-of-the-woods-Unwise-to-bet-on-that.html

Don’t even joke about ending the quiz — I have unsuspected neo-Liberal tendencies that need deprogramming! By the way, for us North-Americans, it is the Friday quiz!

“It is from this point of view that the fight for foreign markets may be viewed. ”

This is the best counter-intuitive explanation of the Chinese mercantilism. The Chinese capitalists do not withdraw the profits as monetary savings on a large scale, they mostly reinvest them and this creates a positive feedback (“acceleration”) – until they reach productive capacities which can satisfy the whole global demand for some commodities. Rising profits not only “finance” investment but also stimulate business confidence and induce credit-financed productive investment.”I” is the parameter which has been maximised in China for the last 30 years up to the point of full utilisation of the productive capacities (which is another limitation not shown in the equations mentioned above). At the previous stage of development production in China was constrained mostly by the productive capital not by demand because they had access to “almost infinite” global demand. Exports were therefore “benefits” and imports were “costs”. Would an alternative path to rapid development based on domestic consumption exist in a country with so high Sw ratio? Not in the current world infested with neoconservatives armed with nukes I am afraid. Also – the Chinese had tried replacing private investment by government investment prior to the reforms but this did not work. Of course when global demand is satisfied by Chinese manufacturing (it may decrease as a result of the global austerity crisis) they will switch to increasing (G-T) or they will reach a plateau in growth like Japan however we are quite far away from that state. Yet Chinese have already overtaken the US as the largest manufacturer. They only need to change the composition of their manufacturing – from pencils, plastic boxes and clothing to computers, iPods, solar panels and space technology – and beyond.

Their persistence may be rewarded.

What about the following book?

“Michal Kalecki” by Julio Lopez G. and Michael Assous, Palgrave 2010

It contains a summary of all the relevant theories developed by Kalecki.

Great article, Bill. I would maintain that as long as certain terminology is used it will elicit certain knee-jerk reactions. “Deficits,” like “government spending” is one of those terms. It suggests irresponsible debt and use of “taxpayers’ money.” This connotation has an avalanche of print behind it, as well as custom. MMT struggles in the face of it will probably not prevail. We must find alternate terminology. Economics, after all, is totally intertwined with politics, hence vulnerable to demagoguery.

Bill,

Great info, as always.

I keep directing folks to this website. Every now and again I will see a report on the natl debt here in the U.S. and I look at all the comments and feel very sad that the deficit fear mongering is working so well.

Have you thought about making some billyblog t-shirts with a cool design and your website on it?

I would buy one and I’m sure a lot of folks would as well. The best part would be getting more people to read your blog.

Just an idea.

Any intelligent person who actually uses their intelligence can deduce alone from first principles and empirically guided thought experiment that key elements of MMT must be correct. In particular, it can be shown that;

Financial Constraints Are Not Real Constraints.

Financial constraints are not real constraints. This statement is conditional in that we must be talking about a self-governing community or a polity for it to be true. For the individual, financial constraints are real constraints. For the individual, overborne by the pressure of the many, social rules and laws can manifest themselves as being just as immutable as the laws of physics. If money must be paid to purchase some goods then the individual cannot take legal possession of those goods without paying that money. If he attempts to do so, legal repercussions follow which might include fines and imprisonment. Customary, social and legal force is soon translated into real force. It is often the case that such law and custom is also applied to incorporated bodies, businesses and companies (and even governments) so that such bodies must also obey the apparent “law of financial constraints”.

From these lessons, the individual can draw the erroneous conclusion that financial constraints are as real and unavoidable for the whole community, in toto, as they are for constituent individuals and incorporated bodies within the community. This false perception that financial constraints are operative at the overall community level (when they need not be) can impede or prevent real and efficacious action that the community could take, especially in times of emergency or crisis.

A simple example can illustrate the truth of the thesis that financial constraints are not real constraints for a self-governing community. Imagine a relatively self-sufficient village economy. This village lives and farms in a valley. Every village householder lives in the village and goes out to farm each day in the surrounding fields. Each village householder owns his own hut and farms his own inherited fields. These possessions are private property but people obey planning and cooperation customs with respect to matters like hut locations, access to fields and the sharing of irrigation waters. The village is Kraal-like in structure and purpose. That is to say it has a timber and brush guard fence around it and people sleep in and defend the village from wild animals and brigands. The irrigation system is a set of channels and long but spindly wooden aqueducts to channel water (from a perennial snow-fed river higher in the mountains) over usually dry ravines and into the traditional farming lands.

We thus see that there are both private properties and community or public works. The kraal fence takes a community effort to build and maintain just as do the irrigation channels and timber aqueducts. The village economy is a mix of self-sufficiency, barter and a money trading economy. Villagers eat their own produce and also barter with each other as some grow grains, legumes and vegetables whilst others herd goats on the higher slopes for meat and milk production. In addition, villagers can sell some produce for the silver coin of the realm to other villages upstream and downstream and to travellers. The villagers find silver coin particularly useful for purchasing timber from timber traders as their own valley is largely denuded of anything larger than firewood brush.

In addition, the traditional direct levy of village labour to build and maintain the kraal fences and the irrigation system has been superseded by a village tax in silver coin on each householder. This revenue is then used to both purchase the necessary timbers and materials from further afield for local community works and to pay local village labourers (some of whom being 2nd, 3rd or 4th sons for example may not have inherited any lands to farm) to do the work. The village, by agreement, also accrues a surplus store of community silver as a hedge against disasters like local crop failure.

Let us now imagine a twin crisis hits the community. First, a serious flood damages many irrigation channels and washes away many timbers of the wood aqueducts such that they are lost forever. The fields are largely unscathed as is the village proper. Secondly, it is then discovered that the village headman has embezzled the entire community store of silver and the community chest is empty. Do the community give up and say they cannot rebuild the irrigation system because they do not have the finances? No, they do not. Instead, they reinstitute the old custom of direct labour levy. Every householder once again directly labours without pay to rebuild the irrigation system. The village day labourers also assist without direct silver coin payment but the villagers agree to feed them (often within the family) and supply their other needs.

Those material needs (new timbers) which cannot be supplied by purchase from distant lumber dealers can be temporarily supplied in other ways. Any spare timbers at all around the village will be given up to the common works. The kraal fence can be “thinned out” of good timbers for the time being and the headman’s very substantial dwelling can be entirely expropriated as a punishment, dismantled timber by timber and applied to the rebuilding of the timber aqueducts.

We can see from this example that financial constraints are not real, absolute constraints for a whole community acting in a cooperative manner. The only constraints are true constraints like labour and materials (timber in this example). These necessities can be supplied with community willingness and imagination provided (and this is an important proviso of course) that the labour and materials do exist in adequate and obtainable quantities in raw physical form.

The emergency methods taken to overcome such a financial system failure will be any or all of;

1. Direct levy of labour for necessary community or public work especially of an emergency or crisis nature;

2. Community contributions of real goods to those who have lost all income but are still contributing real labour to the community or are simply helpless like old widows, orphans.

3. Expropriation of real goods and materials from those who have amassed unconscionable amounts (legally or illegally) relative to real personal need and community standards.

4. Scavenging and temporary or permanent diversion of real goods and materials from less critical (discretionary) needs to more critical and imperative needs.

5. Financial “hiatus accounting” that will record but not currently execute (i.e. leave in indefinite limbo) credits and debts for some possible future settling. Such action might often be taken on the understanding that much of the future slate will be wiped clean in any case due to the possibly radically different nature of the future. However, an accounting of this kind could allow the slate to be selectively wiped clean in a manner the community agrees is the fairest possible to all parties.

Thus we can see that any crisis of a real nature (disasters, resource shortages etc.) can be dealt with by a manipulation of the real labour and real materials left to the community without allowing a purely financial crisis (of financial stores, accounting or flows) to impede real action and real flows of labour and materials. To act in any other manner is to mystify financial accounting and money and to allow a merely notional reality (accounting numbers, metal discs or pieces of paper with notional value) to govern actual reality. To do so is patently absurd. We must not accord the financial system more reality than the usually convenient notional reality it actually has.

It is the plutocrats and financiers, who most benefit from the mystification and legitimation of the artificial finance system of their design and their twisting, who insist that all of the orthodox operations of the financial system must remain sacrosanct, especially the channelling of wealth to a rich minority, even during the worst of crises and always at the expense of the majority who must suffer.

The fact that the business groups often lead the charge against budget deficits reflects the triumph of ideology over good judgement and the triumph of ignorance over understanding.

It should also be noted that, as Kalecki wrote in Political Aspects of Full Employment, “obstinate ignorance is usually a manifestation of underlying political motives.” In that article I think he does a good job answering why business leaders are opposed to policies that help their bottom line, though that’s more of a political matter than an economic one.

It is equally easy to demonstrate from basic principles and empirically guided thought experiments that formal unemployment and formal under-employment (other than frictional unemployment) are unecessary phenomena in a modern fiat money, mixed economy which provides social welfare. These are the preconditions to make the following reasoning true and all these preconditions already exist in fact in our economy (fiat money, mixed economy, welfare.

Proposition 1. There is always more useful work that could be done. This work might involve diminishing returns but it is still worth doing if certain fixed costs mean that a diminishing return is still better than no return.

Proposition 2. Recipients on welfare doing no formal economic work represent a fixed cost (as it were) and a dead loss (no returns) to the formal economy. They might still be doing some useful social and domestic unpaid work outside the formal economy but this does not invalidate formal economic proposition as written.

Proposition 3. Since we are paying them to do nothing (in formal economic terms), we might was well be paying them to do something. This something will be something socially useful not adequately covered by current paid work nor by social and domestic unpaid work and even if only of diminishing or marginal use and productivity this still represents a gain over zero formal productivity (or more correctly over the negative productivity represented by paying something to get “nothing socially useful”*).

Proposition 4. Paying a social wage for a job guarantee will not in practice turn out to be much more expensive up front than paying welfare. A living wage for a person with dependants is not now currently much higher than a living welfare payment for the same person with the same dependants. The downstream productivity and increase in taxes and decrease in formal welfare via the automatic stabilisers could easily render the policy revenue-expenditure neutral (a neat outcome even if not formally or practically required by MMT public finances).

* Note: Actually, in paying welfare we still get some very socially useful outcomes for all classes. We reduce rioting and civil insurrection induced by food shortages, housing shortages etc. We reduce crime, public nuisance and create improve public health by ameliorating the conditions which incubate epidemics in the weakened, starved and neglected part of the populace which epeidemics then spread to the rest of the population.

Sometimes a single graph may tell an entire story. I am following this blog not continuously and not always understandin everything as I am not an economist, but what I have understood is that you focus on spending as the engine for growth.

That can be right, provided spending is directed to the proper direction.

Let’s see the graph of the net private investments as a percent of GDP. Let’s take out he years from 1930 to 1950, as they are not really representative, Great Depression first and WW II after, and let’s focus on the “normal” years after.

You write that over the entire period the average was 8.1 %, but, using the scale you use and considering the out-of-normality years, it is difficult to see the point.

In the most prosperous years, say 1950 to 1970, the investments were at 10 % or even slightly higher. People were not consuming all they income but they were re-investing in new opportunities.

After 1970 the investments progressively declined going down to 6-7 % with a sharp drop in the last few yeats in the Great Recession years.

IMHO people have reduced their investments focusing in consumptions, that, by the way, are not good for the health of the planet too, as the role of the governments, the Big Father and Big Mother, progressively expanded, something that historically has occurred since the 70’s. Why one should take care of saving-investing when there is government that is always ready to provide money to you?

The point is that money is worth nothing if there is nothing to buy. And if investments decline, progressively there will be less to buy.

If governemnts spend to ditch holes (and most public employees are practically doing that), for some years the will be an apparent prosperity while money flows. But people doing nothing do not generate anything for the community. Rather, the other people have to work more to produce the food, the houses, the cars, that those doing nothing are in any case consuming. And sooner or later they will realize that. But the problem is that the governements are the forcing them to go on working in order to continue the subside to the public employees. Till the system will collapse.

The point therefore has to be: work and produce something worth for the consumers, not something that noone will buy if free to decide but theat must be produced by governement decree, do not consume everything but save and re-invest.

“it makes no sense to drive an economy into recession where it stops people from working and thus paying more taxes” if the goal is to reduce budget deficits.

If the consequences of elite action appear to confound their stated goals, then perhaps we should revisit the assumption that their true goals are identical to their stated goals. It’s comforting to believe that they’re stupid, but that’s extraordinarily naive.

Ikonoclast, those were very enlightening comments

If the consequences of elite action appear to confound their stated goals, then perhaps we should revisit the assumption that their true goals are identical to their stated goals. It’s comforting to believe that they’re stupid, but that’s extraordinarily naive.

Well, given that I know where my Prime-minister (Portugal) graduated, and that the Prime-minister before him had a fake diploma in Engineering, I’m not so sure it’s naive to believe they’re stupid.

Bill leave the quiz alone! It’s the only thing that keeps me (in)sane although I am still (on average) a raving neoliberal…

And yes, good piece by Simon Jenkins

Vincenzo says, “If governments spend to ditch (sic) holes (and most public employees are practically doing that), for some years there will be an apparent prosperity while money flows. But people doing nothing do not generate anything for the community. Rather, the other people have to work more to produce the food, the houses, the cars, that those doing nothing are in any case consuming.”

I have already answered this style of objection but I want to quickly answer the slur against public servants.

The claim is that most public employees do practically nothing. Whilst not claiming that all public employees are paragons of hard working virtue, I will point out that most do actually do things that the community needs. Public utilities are built and run, roads are repaired and public services actually provide service.

In Australia, we had the Commonwealth Bank and the PMG (later Telstra) built up and run by pubic servants. The proof that these public servants actually built and ran something lies in that fact that these utilities were eventually sold to private enterprise for many billions and even that was with a deliberate under-pricing policy which amounted to a wealth transfer from common public wealth to minority private wealth.

It is not easy (for example) to work at a govt welfare front counter all day dealing with angry, frustrated, long-term unemployed people whilst attempting to apply ill-conceived government policy that is a based on inapplicable ideology and designed essentially to appeal to various middle class and upper prejudices to win votes.

I have worked in private and public enterprise in my time. I found, for example, the job of machinery operator in private enterprise (on a front front end loader digging holes ironically enough) much easier and far less stressful than clerical and customer work in a federal welfare office. The pay rates were about the same. Basic clerical work in a private enterprise bank was also easier than federal welfare office work. This claim that all public servants do virtually nothing and have it easy while all private enterprise workers are always doing vital, worthwhile work (at times on the loader I was digging holes so rich, spoiled people could have bigger backyard pools) just doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

@Ikonoclast.

I do not know the situation in Australia, I know it in my country, Italy. And when I say that most of public employees do nothing, I do not mean they are lazy or that at the end of the day they are not tired, probably even more than a private employee (most of my relatives, including my parents, are/were public employees, so I know very well what they do/did). I mean most of them do nothing USEFUL. Most of the times they do things that are just slowing down the economy, such as intoducing absurde rules whose only purpose is to to justify their employement. It is obviously not a fault on the single person, it a fault of the system.

Why to move a door inside my home I have to submit tons of papers and wait the approval of several people? Is there any logic reason for that? Is there any logic reason why the regulations to build a new house are something like 300 pages?

Is there any logic reason why the public admistration is asking me many times to provide infromation they already have in another office?

Why if I want to start importing chloridric acid, something that everyone uses normally to clean the toilet closet, from Australia I have to go through the absurde REACH registration as it is something totally unknown and sepnd half a million?

Why even paying taxes is difficult?

Why a small family laundry should follow for its wastes the same rules of a huge oil refinery?

I appreciate the job that is made by those bulding roads or by the healtcare system. But I do not appreciate the useless things.

Look carefully to public employement and then ask yourself: if one of their activities is going to disappear magically from this moment on, will there be any consequence to the society?

Well, if computer manufacturers suddenly disappear from the globe, I am sure you will feel the difference, not so sure for may public jobs.

“When workers increase their saving, gross profits fall because less of the workers’ income is coming back to the firms as consumption spending. When, in Kalecki’s words – the workers spend what they get – that is, in his simple two-sector model workers are assumed not to save at all (Sw = 0), then the capitalist profits are maximised from this source (other things equal).”

Yes. But I think you don’t draw out the next step from this equation, which has been crucial to our economy over the last couple of decades.

Profits are further maximised when workers spend more than what they get, ie go into debt. This seems to have been above all else, especially in the uk though elsewhere as well, the driving force of increasing profits. Probably more so than government deficits.

This is Steve Keen’s big thing, and he’s quite right to draw attention to it.

“politicians in Europe and the UK are deliberately sabotaging their economies”

Bill,

“deliberately” precludes ignorance & stupidity, yet your article supports the latter. Which is it?

If deliberate, then call in the criminologists, without delay.

@ Vincenzo

That’s a good idea. Look carefully at public employment. In numerical terms, the vast number of public employees are in sectors such as health, transportation, education, defense, law enforcement. They are teachers, nurses, policemen, bus drivers. The type of civil servant you apparently have in mind who drafts and enforces new regulations is rather a small part of the total. So choose a random public servant, and choose a random private sector worker if you will, and imagine eliminating their job. Personally, I’d bet that losing the public servant caused more damage to society.

As to those civil servants who do spend their time working on regulations, be specific about the things they do that are not benefiting society. If it turns out that small family-run laundries are being forced to complete 50 pages of material safety and disposal documentation every quarter then I’ll be the first to support a small business exemption. If you’re objection to regulation is more along the lines of “I think small family-run laundries should be allowed to pour raw bleach down the drain”, then I’m quite comfortable in saying that the civil servant who drafts and enforces that regulation is providing plenty of benefit to society.

About public employment, our Governments have been leading successive campaigns against public employees, with some nefarious effects – the Governments have been cutting pay and benefits in a way such that is much more profitable for the competent individual to work in the private sector, where he’ll receive more and work much less. The result is that the public sector is left with employees that don’t work or that are not competent in their work. It’s a vicious circle, leading people to think even less of public workers and supporting further cuts which shall degrade the public service even further.

Kay Fabe is obviously missing some crucial structure of MMT but ironically makes a point.

Breaking KayFabe is breaking the fact that choreographed wrestling and feuds are not real, so perhaps the Treasuries and Central banks of the world do understand MMT for the most-part but it is not the economic lessons we were brought up on and thus are afraid of breaking kayfabe.