Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday quiz – January 28, 2012 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

During the American Civil War, the Confederate states experienced rising inflation as a result of their war spending in 1861. The Confederate Government could have eased the inflationary impact of this spending by issuing more bonds than it did.

The answer is False.

The key is in understanding that bond sales do not drain demand.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The writer fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

The textbook argument claims that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made.

Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target.

Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance.

So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Printing money does not cause inflation

Question 2:

Eurozone nations can only alter their international competitiveness by reducing domestic wages and prices because they no longer have a floating currency.

The answer is False.

The temptation is to accept the rhetoric after understanding the constraints that the EMU places on member countries and conclude that the only way that competitiveness can be restored is to cut wages and prices. That is what the dominant theme emerging from the public debate is telling us.

However, deflating an economy under these circumstance is only part of the story and does not guarantee that a nations competitiveness will be increased.

We have to differentiate several concepts: (a) the nominal exchange rate; (b) domestic price levels; (c) unit labour costs; and (d) the real or effective exchange rate.

It is the last of these concepts that determines the “competitiveness” of a nation. This Bank of Japan explanation of the real effective exchange rate is informative. Their English-language services are becoming better by the year.

Nominal exchange rate (e)

The nominal exchange rate (e) is the number of units of one currency that can be purchased with one unit of another currency. There are two ways in which we can quote a bi-lateral exchange rate. Consider the relationship between the $A and the $US.

- The amount of Australian currency that is necessary to purchase one unit of the US currency ($US1) can be expressed. In this case, the $US is the (one unit) reference currency and the other currency is expressed in terms of how much of it is required to buy one unit of the reference currency. So $A1.60 = $US1 means that it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US.

- Alternatively, e can be defined as the amount of US dollars that one unit of Australian currency will buy ($A1). In this case, the $A is the reference currency. So, in the example above, this is written as $US0.625= $A1. Thus if it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US, then 62.5 cents US buys one $A. (i) is just the inverse of (ii), and vice-versa.

So to understand exchange rate quotations you must know which is the reference currency. In the remaining I use the first convention so e is the amount of $A which is required to buy one unit of the foreign currency.

International competitiveness

Are Australian goods and services becoming more or less competitive with respect to goods and services produced overseas? To answer the question we need to know about:

- movements in the exchange rate, ee; and

- relative inflation rates (domestic and foreign).

Clearly within the EMU, the nominal exchange rate is fixed between nations so the changes in competitiveness all come down to the second source and here foreign means other nations within the EMU as well as nations beyond the EMU.

There are also non-price dimensions to competitiveness, including quality and reliability of supply, which are assumed to be constant.

We can define the ratio of domestic prices (P) to the rest of the world (Pw) as Pw/P.

For a nation running a flexible exchange rate, and domestic prices of goods, say in the USA and Australia remaining unchanged, a depreciation in Australia’s exchange means that our goods have become relatively cheaper than US goods. So our imports should fall and exports rise. An exchange rate appreciation has the opposite effect.

But this option is not available to an EMU nation so the only way goods in say Greece can become cheaper relative to goods in say, Germany is for the relative price ratio (Pw/P) to change:

- If Pw is rising faster than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively cheaper within the EMU; and

- If Pw is rising slower than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively more expensive within the EMU.

The inverse of the relative price ratio, namely (P/Pw) measures the ratio of export prices to import prices and is known as the terms of trade.

The real exchange rate

Movements in the nominal exchange rate and the relative price level (Pw/P) need to be combined to tell us about movements in relative competitiveness. The real exchange rate captures the overall impact of these variables and is used to measure our competitiveness in international trade.

The real exchange rate (R) is defined as:

R = (e.Pw/P)

where P is the domestic price level specified in $A, and Pw is the foreign price level specified in foreign currency units, say $US.

The real exchange rate is the ratio of prices of goods abroad measured in $A (ePw) to the $A prices of goods at home (P). So the real exchange rate, R adjusts the nominal exchange rate, e for the relative price levels.

For example, assume P = $A10 and Pw = $US8, and e = 1.60. In this case R = (8×1.6)/10 = 1.28. The $US8 translates into $A12.80 and the US produced goods are more expensive than those in Australia by a ratio of 1.28, ie 28%.

A rise in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e depreciates; and/or

- Pw rises more than P, other things equal.

A rise in the real exchange rate should increase our exports and reduce our imports.

A fall in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e appreciates; and/or

- Pw rises less than P, other things equal.

A fall in the real exchange rate should reduce our exports and increase our imports.

In the case of the EMU nation we have to consider what factors will drive Pw/P up and increase the competitive of a particular nation.

If prices are set on unit labour costs, then the way to decrease the price level relative to the rest of the world is to reduce unit labour costs faster than everywhere else.

Unit labour costs are defined as cost per unit of output and are thus ratios of wage (and other costs) to output. If labour costs are dominant (we can ignore other costs for the moment) so total labour costs are the wage rate times total employment = w.L. Real output is Y.

So unit labour costs (ULC) = w.L/Y.

L/Y is the inverse of labour productivity(LP) so ULCs can be expressed as the w/(Y/L) = w/LP.

So if the rate of growth in wages is faster than labour productivity growth then ULCs rise and vice-versa. So one way of cutting ULCs is to cut wage levels which is what the austerity programs in the EMU nations (Ireland, Greece, Portugal etc) are attempting to do.

But LP is not constant. If morale falls, sabotage rises, absenteeism rises and overall investment falls in reaction to the extended period of recession and wage cuts then productivity is likely to fall as well. Thus there is no guarantee that ULCs will fall by any significant amount.

Question 3:

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is consistent with the claim that government spending can crowd out private spending.

The answer is True.

The question explores the differences between “real crowding out” and the more commonly-used notion (by mainstream economists) of “financial crowding out”.

The normal presentation of the crowding out hypothesis which is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention is more accurately called “financial crowding out”.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory. Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

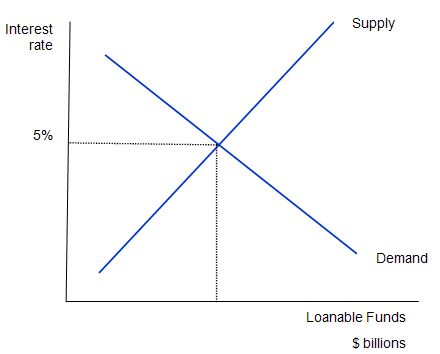

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment. Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that budget surpluses are akin to this. They are not even remotely like private saving. They actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of budget surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to “any other market in the economy” despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates – read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consquences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a budget deficit. Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

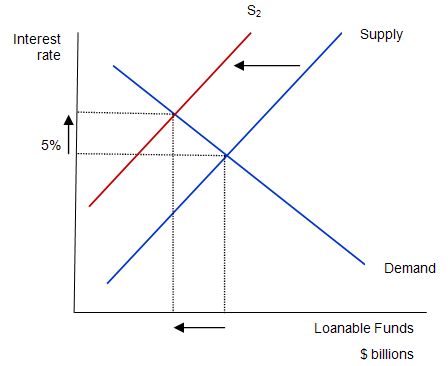

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2. Why does that happen? The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising budget deficit reduces public saving and available national saving. The budget deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Sometimes, this makes is hard to know where to start in debunking it. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no! Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors. Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading “financial crowding out”.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

However, other forms of crowding out are possible. In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

Further, while there is mounting hysteria about the problems the changing demographics will introduce to government budgets all the arguments presented are based upon spurious financial reasoning – that the government will not be able to afford to fund health programs (for example) and that taxes will have to rise to punitive levels to make provision possible but in doing so growth will be damaged.

However, MMT dismisses these “financial” arguments and instead emphasises the possibility of real problems – a lack of productivity growth; a lack of goods and services; environment impingements; etc.

Then the argument can be seen quite differently. The responses the mainstream are proposing (and introducing in some nations) which emphasise budget surpluses (as demonstrations of fiscal discipline) are shown by MMT to actually undermine the real capacity of the economy to address the actual future issues surrounding rising dependency ratios. So by cutting funding to education now or leaving people unemployed or underemployed now, governments reduce the future income generating potential and the likely provision of required goods and services in the future.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues. If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that. It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example). But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

Question 4:

In its latest Monthly Budget Review, the US Congressional Budget Office announced that the US “federal budget deficit was $320 billion for the first quarter of fiscal year 2012 … $49 billion less than the deficit recorded in the same period in fiscal year 2011”. Without knowing anything further, you would conclude that the US government has been cutting its discretionary net spending.

The answer is False.

The question probes an understanding of the forces (components) that drive the budget balance that is reported by government agencies at various points in time. The answer is False because there are situations that could arise (although highly unlikely) which would contradict the statement about the movements in the deficit ratio being driven by a “discretionary contraction in net public spending”.

In outright terms, a budget deficit that is equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP is more expansionary than a budget deficit outcome that is equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP. But that is not what the question asked. The question asked whether that signalled that the government is adopting a less expansionary policy – that is, whether its discretionary fiscal intent was expansionary.

In other words, what does the budget outcome signal about the discretionary fiscal stance adopted by the government.

To see the difference between these statements we have to explore the issue of decomposing the observed budget balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the budget process.

The federal (or national) government budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit or the deficit increases as a proportion of GDP doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-

Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So the data provided by the question could indicate a more contractionary fiscal intent from government but it could also indicate a large automatic stabiliser (cyclical) component as the economy was growing. The fact is that it indicates a bit of both in the case of the US at present but you were asked to suspend any further knowledge and just use conceptual logic.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Premium Question 5:

When net exports are negative, government deficits are required if private households are to save overall.

The answer is False.

This question is an application of the sectoral balances framework that can be derived from the National Accounts for any nation. It also has a in-built trap because while the first two balances refer to the broad macroeconomic sectors (external and government) the third “balance” refers to a subset of the private domestic sector – households. Households can still save overall even if the private domestic sector is in deficit.

The statement would have been true if it had have read “When net exports are negative, government deficits are required if private domestic sector is to save overall”.

The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

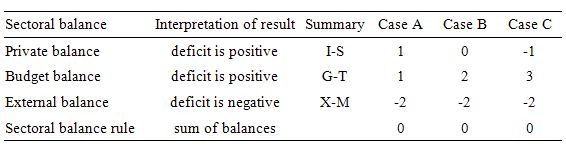

To help us answer the specific question posed, we can identify three states all involving public and external deficits:

- Case A: Budget Deficit (G – T) < Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case B: Budget Deficit (G – T) = Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case C: Budget Deficit (G – T) > Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

The following Table shows these three cases expressing the balances as percentages of GDP. Case A shows the situation where the external deficit exceeds the public deficit and the private domestic sector is in deficit. In this case, there can be no overall private sector de-leveraging.

With the external balance set at a 2 per cent of GDP, as the budget moves into larger deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance (Case B). Case B also does not permit the private sector to save overall.

Once the budget deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) the private domestic sector can save overall (Case C).

In this situation, the budget deficits are supporting aggregate spending which allows income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector but have to be able to offset the demand-draining impacts of the external deficits to provide sufficient income growth for the private domestic sector to save.

For the domestic private sector (households and firms) to reduce their overall levels of debt they have to net save overall. The behavioural implications of this accounting result would manifest as reduced consumption or investment, which, in turn, would reduce overall aggregate demand.

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms lay-off workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession.

So the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur. Given the question assumes on-going external deficits, the implication is that the exogenous intervention would come from an expanding public deficit. Clearly, if the external sector improved the expansion could come from net exports.

It is possible that at the same time that the households and firms are reducing their consumption in an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public budget balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving overall if net exports were strong enough.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

So households can still be saving overall but private investment would be greater which means that the private domestic sector overall would be spending more than it is earning.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Bill –

I disagree with your answer to question 1. Your solution has several flaws:

You assume the mid 19th century situation was the same as the situation today, but that seems rather unlikely. Commercial banks haven’t always been as eager to lend as they have in the last few years, you have provided no evidence that they were as unconstrained by reserve requirements a century and a half ago as they are now, and there is also the possibility that banks could be limited by capital constraints.

You assume bond sales would be driven by economic considerations, but there’s also the possibility that they could be driven by patriotic fervour – after all, there was a war on!

And you are assuming that draining demand is the only effect bond sales could have. It’s possible some of the extra bonds could have been sold overseas, reducing inflation by increasing the value of the currency.

Bond sales are unlikely to have much effect on inflation now, but that’s not what you asked.

Bill – WRT Q1 – I agree with your general analysis but in the specific case of the Confederacy it seems to me that bond sales might have, in principle at least, have reduced the inflationary impact of its spending. In the modern situation, as you say, bond sales merely alter the composition of private sector assets, however, if the Confederacy had been able to force at least some if its creditors to accept bonds instead of currency (and these bonds did not circulate as a means of settling debt) then, effectively the bond issuance could have forced additional saving on the non-government sector. In principle, this would then have reduced spending and inflation from the level it would have been if the Confederacy’s creditors had received currency.

I thought a major issue for the confederacy arose from its inability to implement any sort of meaningful tax policy, also, sort of back to question 3, the military mobilization of the confederacy would have outstripped the capacity of their new nation to produce.