I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The skill shortage ruse is re-appearing

I had a meeting today with well-known personnel management professional who is keen to fund some research on skills development. It is a topic that my research group has concentrated on for many years now. It is an interesting topic because it bridges the technical and the political. There is a pattern emerging, as it always does when we have recession, which seeks to deflect attention to what is really going in favour of promoting “faux” issues. The “skills shortage” claim by business lobby groups and peak bodies is one of the perennial examples of the way the elites deny that the system is failing to produce enough jobs and helps them deflect the blame onto individuals – the victims – the unemployed. The ruse is used then to pressure governments into further undermining the rights of workers and conditions of work (and reducing welfare benefits) which serve the interests of the elites. So the constraints on growth become constructed in terms of the laziness of the unemployed workers to invest in themselves. This narrative then diverts our attention from the real causes of stagnation and unemployment – not enough spending and not enough jobs. We fall for it every time.

Recall this UK Guardian article (May 18, 2010) – Skills shortage is getting worse, bosses warn.

It is always amusing to reflect back on the press train which is typically influenced by the political spin and the hype coming from the IMF, OECD and like institutions.

In May 2010 in Britain the employers claiming that:

… they will be unable recruit students with the skills they need as the economic recovery kicks in … As we move further into recovery and businesses plan for growth, the demand for people with high-quality skills and qualifications will intensify

And so it went. Luckily David Cameron was elected about then and fixed the problem in his government’s first budget. They just killed the emerging growth.

Then there was this article in the Telegraph (August 26, 2010) – UK skills shortages: do they really exist? – that introduced a new take on the issue:

The article reported that:

Thousands of qualified and over-qualified candidates are looking for their next job right now. Many have built up years of experience in their specific sector or trade, with enviable skills, expertise and qualifications that young school leavers could only dream of. Why then, are they strugggling to find a job?

Clearly, there are fewer jobs around right now. They are also a more expensive category of candidate to hire.

But of the jobs that are being advertised (and where employers are willing to pay a premium), I am finding that companies are becoming ever more picky about who they hire. It’s not actually about “skills shortages” – so many employers blame a dearth of talent for not being able to fill posts – but actually, what they mean is that they cannot find the right type of person to fill their role.

Personality, attitude, cultural fit. These are all things that are put first, above and beyond skills and qualifications on paper. If you are fully trained but won’t “fit in” with an organisation’s values then you don’t stand a chance against hundreds of other applicants.

The old “structural unemployment” ruse – skill mismatches – but it often turns out that there are workers available that employers do not “like” because of their skin colour, appearance, etc.

The concept of a skills shortage is clearly a relative concept, implying some distance from an optimal state, which begs the question: according to whom.

Unsurprisingly, analyses of skills shortages by industry and governments invariably consider the issue from the perspective of business and profitability, which places the emphasis on containment of labour costs both in terms of wages and conditions, and hence, whenever possible, externalising the costs associated with developing the skills firms require in their workers.

Within this context, the notion of structural unemployment arising from “skills mismatch” can be understood as implying an unwillingness of firms to offer jobs (with attached training opportunities) to unemployed workers that they deem to have undesirable characteristics.

When the labour market is tight, the willingness of firms to indulge in their prejudices is more costly. However, when labour underutilisation is high, firms can easily increase their hiring standards (broaden the desired characteristics they demand from workers) and the training dynamism driven by labour shortages is lost. Then we observe, in a static sense, “skill mismatches” which are really symptoms of a “low pressure” economy.

Structural unemployment has long been a hideout for employers intent on exercising their prejudices and being able to in a slack market with little cost.

Then think about recent comments by one of the more extreme (on the lunatic index) Republican candidates – Herman Caine. He recently gave an interview to the Wall Street Journal. He said (thanks to Daily Kos for the transcript):

I don’t have facts to back this up, but I happen to believe that these demonstrations are planned and orchestrated, to distract from the failed policies of the Obama administration … Don’t blame Wall Street, don’t blame the big banks … if you don’t have a job and you are not rich, blame yourself!

It is crazy stuff really but reflects the underlying neo-liberal narrative that there is no systemic failures in macroeconomics. All outcomes are driven by individual choices and if you don’t have a job then there must be something wrong with you!

I considered these issues in my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned.

We traced the demise of what we called the full employment framework and its ultimate replacement with the diminished full employability framework. We noted that under the former framework, everybody who wanted to earn an income was able to find employment. Maintaining full employment was an overriding goal of economic policy which governments of all political persuasions took seriously.

The full employment framework has been systematically abandoned in most OECD countries over the last 30 years. The overriding priority of macroeconomic policy has shifted towards keeping inflation low and suppressing the stabilisation functions of fiscal policy. Concerted political campaigns by neo-liberal governments aided and abetted by a capitalist class intent on regaining total control of workplaces, have hectored communities into accepting that mass unemployment and rising underemployment is no longer the responsibility of government.

As a consequence, the insights gained from the writings of Keynes, Marx and Kalecki into how deficient demand in macroeconomic systems constrains employment opportunities and forces some individuals into involuntary unemployment have been discarded. The concept of systemic failure has been replaced by sheeting the responsibility for economic outcomes onto the individual.

Accordingly, anyone who is unemployed has chosen to be in that state either because they didn’t invest in appropriate skills; haven’t searched for available opportunities with sufficient effort or rigour; or have become either “work shy” or too selective in the jobs they would accept.

Governments are seen to have bolstered this individual lethargy through providing excessively generous income support payments and restrictive hiring and firing regulations. The prevailing view held by economists and policy makers is that individuals should be willing to adapt to changing circumstances and individuals should not be prevented in doing so by outdated regulations and institutions. The role of government is then prescribed as one of ensuring individuals reach states where they are employable.

In this blog – The Great Moderation myth – I quoted one of the doyens of neo-liberalism.

In the 2003 presidential address to the American Economic Association, Robert E. Lucas, Jnr of the University of Chicago said:

My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. There remain important gains in welfare from better fiscal policies, but I argue that these are gains from providing people with better incentives to work and to save, not from better fine tuning of spending flows. Taking U.S. performance over the past 50 years as a benchmark, the potential for welfare gains from better long-run, supply side policies exceeds by far the potential from further improvements in short-run demand management.

So governments were lulled into thinking the “business cycle was dead” and were pressured into microecnomic agendas. They set about reducing the ease of access to income support payments via pernicious work tests and compliance programs; reducing or eliminating other “barriers” to employment (for example, unfair dismissal regulations); and forcing unemployed individuals into a relentless succession of training programs designed to address deficiencies in skills and character.

We called that the full employability framework and it is exemplified in the 1994 Jobs Study published by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Its main message (OECD, 1994, vii) accurately summarises the current state-of-the-art in policy thinking:

… it is an inability of OECD economies and societies to adapt rapidly and innovatively to a world of rapid structural change that is the principal cause of high and persistent unemployment … Consequently, the main thrust of the study was directed towards identifying the institutions, rules and regulations, and practices and policies which have weakened the capacity of OECD countries to adapt and to innovate, and to search for appropriate policy responses in all these areas … Action is required in all areas simultaneously for several reasons. First, the roots of structural unemployment have penetrated many if not all areas of the socioeconomic fabric; second, the political difficulties of implementing several of these policies call for a comprehensive strategy … third, there are synergies to exploit if various microeconomic polices are pursued in a co-ordinated way, both with regard to each other and the macroeconomic policy stance.

The OECD Jobs Study (1994: 74) also ratified the growing macroeconomic conservatism by articulating that the major task for macroeconomic policy was to allow governments to ‘work towards creating a healthy, stable and predictable environment allowing sustained growth of investment, output and employment. This implies a reduction in structural budget deficits and public sector debt over the medium term … [together with] … low inflation.’

Prior to the financial crisis, the OECD consistently claimed that its policy recommendations were delivering successes in countries that have implemented them. Unfortunately, the reality is strikingly at odds with this political hubris. Even with more than a decade of fairly stable economic growth in most nations leading up to the crisis, most countries still languished in high states of labour underutilisation and low to moderate economic growth.

Further, underemployment is becoming an increasingly significant source of wastage. Youth unemployment remains high. Income inequalities are increasing. The only achievement is that inflation is now under control, although it was the severity of the 1991 recession that expunged inflationary expectations from the OECD block. Since that time, labour costs have been kept down by harsh industrial relations deregulation and a concerted attack on the labour unions.

The policy approach used to banish one of the twin evils – inflation – has left the evils of unemployment and underemployment in its wake. The result is that after 30 years of public expenditure cutbacks and, more recently, increasing government bullying of the jobless, OECD economies generally did not get close to achieving full employment.

These pathologies have magnified as a result of the recent crisis and the policy frameworks established under the aegis of the OECD Jobs Study have only made workers more vulnerable than they otherwise would have been.

In the midst of the on-going debates about labour market deregulation, scrapping minimum wages, and the necessity of reforms to the taxation and welfare systems, the most salient, empirically robust fact of the last three or more decades – that actual GDP growth has rarely reached the rate required to maintain, let alone achieve, full employment – has been ignored.

An understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) allows one to lay most of the blame for this labour underutilisation across OECD countries lies with the policy failures of national governments. At a time when budget deficits should have been used to stimulate the demand needed to generate jobs for all those wanting work, various restrictions have been placed on fiscal policy by governments influenced by orthodox macroeconomic theory.

Monetary policy has also become restrictive, with inflation targeting – either directly or indirectly – pursued by increasingly independent and vigilant central banks. These misguided fiscal and monetary stances have damaged the capacities of the various economies to produce enough jobs.

The attacks on the welfare system have, in part, been driven by the overall distaste among the orthodox economists for the activist fiscal policy essential to the maintenance of full employment. Counter-cyclical fiscal policy is now eschewed and monetary policy has become exclusively focused on inflation control. There are many arguments (fears) used to justify this position, including the (alleged) dangers of inflation and the need to avoid crowding out in financial markets.

The skills shortage narrative is intrinsic to this neo-liberal construction of the world. Systemic failure (lack of demand) give way to individual failure (lack of skills).

Growth is hampered by ill-prepared individuals rather than lack of overall spending. That has been the dominant theme of the neo-liberal years.

I was thinking about this again today when I read this recent report from Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute in the US (published October 17, 2011) – Boiling Point? The skills gap in U.S. manufacturing.

Unless this is a field of interest I would waste my time reading the report. The summary is simple:

The survey … polled a nationally representative sample of 1,123 executives at manufacturing companies recently and revealed that 5 percent of current manufacturing jobs are unfilled due to a lack of qualified candidates … The survey shows that 67 percent of manufacturers have a moderate to severe shortage of available, qualified workers … Moreover, 56 percent anticipate the shortage to increase in the next three to five years.

In September 2011, Manufacturing employment was 11741 thousand. So according to the Skills Gap Report, there are an additional 587 thousand jobs that would be created if they could find the workers.

They concluded that:

Think of it this way: as many as 600,000 well-paying jobs are going unfilled while the national unemployment rate hovers around 9%.

Well I would say think about it this way.

In September 2011, there were 13,992 thousand people “officially” unemployed. We could easily double that if we wanted to include the US Bureau of Labour Statistics broader measures of labour underutilisation.

So it is somewhat of a stretch to consider a small constraint on manufacturing (if true) to be the cause of the labour market failure in the US. But it does serve to deflect attention from the 26 odd millions workers who are being excluded from work by the failure of the US government to manage aggregate demand correctly.

And then consider the logic of the claim. 600,000 thousand workers at the current productivity level in manufacturing would create a lot of output. That output, apparently, is not being produced but could be if there were workers available if the Skills Gap Report is to be taken literally.

That would represent a very large volume of unfilled orders sitting on the companies order books (or by implication somewhere). Think about that in terms of a competitive industry. If there was that frustrated demand some firm would work out a way to satisfy it and thus gain market share.

The fact is that no survey reveals that level of unmet demand (that is, consumers or firms with cash to spend who systematically cannot purchase goods because the firms have said they cannot supply them because of labour shortages.

There was a Report put out by the US Congressional Budget Office – What Accounts for the Decline in Manufacturing Employment? on February 18, 2004.

They commented at the time that:

Much of the decline in manufacturing employment since 2000 reflects the recession that began in 2001 and the relatively weak recovery in demand that followed. The recession was particularly hard on the manufacturing sector, as the demand for goods weakened in both the United States and the rest of the world.

That is, confirming the cyclical-sensitivity of the sector which is a common global phenomena.

The CBO also note that “long-term trends indicate that even after the economy has fully recovered from the 2001 recession, employment in manufacturing is unlikely to return to its prerecession level”.

What is driving this structural decline? Several factors are noted including increased productivity; increasing spending on “spending to services instead of goods”; “competition from countries where businesses face lower compensation costs”; and increased use of “contract and temporary labor”.

On the last point, the CBO said:

… manufacturing employers increasingly have met short-term fluctuations in demand not by adding permanent staff but by hiring temporary workers through agencies and by contracting with outside firms to provide certain support functions (for example, cafeteria, janitorial, and payroll-processing services) … But because temporary workers are typically the first to be let go when demand weakens, how much (if any) of the decline in manufacturing jobs since 2000 can be ascribed to the structural change in the sector is unclear. And as the economy recovers, some portion of the rebound in manufacturing employment is likely to be obscured by the hiring of temporary workers and contracting with outside firms.

Further, if you consult the latest US Federal Reserve measures of capacity utilisation you will see that peak manufacturing capacity utilisation was 85.5 per cent in 1988-89. It is currently (September 2011) at 75.1 per cent and has been growing slowly as the US economy recovers.

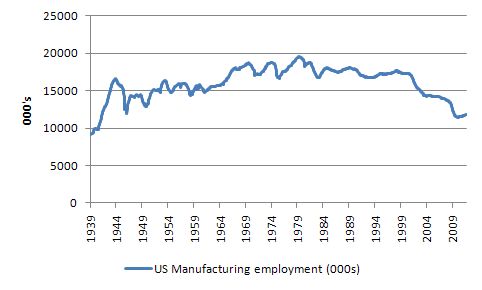

To reinforce the CBO findings and to consider them in the light of the recent crisis, the following graph shows US manufacturing employment (thousands) since 1939 (up to September 2011) – data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. It is clear the the sector has been in decline for many years.

In 1939, US manufacturing compromised about 31 per cent of total non-farm employment. It has been falling steadily since that time. In 2011 it is about 8.9 per cent of total employment.

The terminal decline started in the late 1990s and for the next from November 1998 to until September 2011 (155 months in total) the annual growth in manufacturing employment was negative for 139 months (that is, 90 per cent).

The decline has nothing to do with skills shortages.

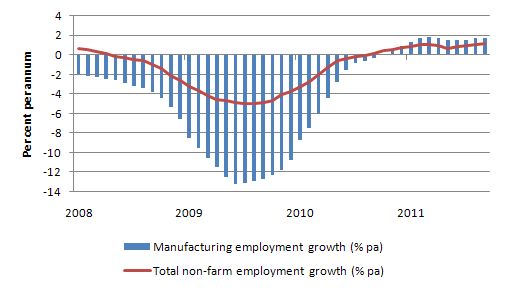

Moreover consider the following graph which shows the annual growth in Manufacturing employment (blue bar) and Total non-farm employment (red line) since December 2007.

The swings in manufacturing employment were in concert with the demand cycle for the overall economy although they were more severe. A similar chart from 1939 reveals the same pattern. Strong cyclical swings in line with the national economy.

The question is, of-course, if you have 25 million workers who are idle in some form why won’t firms offer them employment and training slots?

The Skills Gap Report does suggest that employers could “take steps to expand the skills base of their existing workforce”. But they use “outdated” methods of recruitment and when “it comes to training, there is also considerable room for improvement”.

The fact is that the business sector in the US (and Australia etc) have appalling records when it comes to developing skills.

This discussion relates to one of the advantages of maintaining economies at full employment (“high pressure”).

A “high pressure” economy not only maximises output but also enhances labour force participation and provides strong incentives for employers to tailor training and paid-work opportunities to attract scarce labour. When labour is in excess supply (high unemployment) employers lose this incentive and the dynamic skill-building process falters.

From 1945 to the mid 1970s, Australia, like most advanced western nations, maintained very low levels of unemployment (rarely above 2 per cent). This era was marked by the willingness of governments to maintain levels of aggregate demand that would create enough jobs to meet the preferences of the labour force, given labour productivity growth. Governments used a range of fiscal and monetary measures to stabilise the economy in the face of fluctuations in private sector spending.

During the true full employment period unfilled vacancies usually outstripped the unemployed. There was no underemployment over this period.

The sustained full employment forced employers to compete for workers as they sought to expand market share. The upshot was that for every job that was offered, a corresponding training opportunity was also created.

Firms were forced to offer training slots with paid-employment opportunities because they had to scramble for scarce labour. Once governments abandoned full employment as an objective firms started to abandon training and relied on the government creating a surplus pool of labour that they could pick and choose from.

The dual instance of high rates of labour underutilisation and skills shortages reflect a monumental policy failure to generate enough jobs overall – the two problems are two sides of the same coin.

The reality is that training is also most effective when combined with a paid-work opportunity. Firms that expect a skilled workforce to be provided to them are avoiding their responsibilities to develop skills within the paid-work context – with ladders of apprentices and teachers being created.

I have been reading an interesting book that crosses this terrain. It is written by Gordon Lafer – The Job Training Charade (published 2002).

Lafer exposes many of the myths about job training, which has replaced direct public sector job creation as the answer to unemployment. That is, the focus under the full employability framework shifted to so-called “supply-side” measures in denial of deficient demand.

Lafer traces that shift in the US to the Ronald Reagan era and the Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA). At the height of the 1982 recession, Reagan continually claimed there were plenty of jobs but the problem was a lack of appropriate skills. The JTPA was the political window-dressing to support that neo-liberal rhetoric.

He demonstrates that the JTPA was not effective in developing productive skills and allowing workers to enjoy a stable attachment to employment.

The Job Training Charade categorically exposes these myths and demonstrates that the reason there is unemployment (and underemployment) in the US is because there are not enough jobs created rather than a deficiency of skills.

Lafer exposes the so-called link between human capital development (education) and wage outcomes saying that the “the relationship between education and wages is extremely weak”.

So the Occupiers have another strand of orthodoxy to attack and disassemble. The skills shortage narrative is part of the overall strategy that the elites use to maintain their denial that the economic system is producing enough jobs. It entrenches their power and broadens the smokescreen surrounding corporate failure – by blaming the victims.

As Lafer says in his book:

Workers are encouraged not to blame corporate profits, the export of jobs aboard, or eroding wage standards-that is, anything that they can fight-but rather to look inward for the source of their misfortune and the seeds of their resurrection.

He suggests that the “skills gap” narrative is a “political strategy” rather than a “policy issue” designed to garner public subsidies for business. That is, it is part of the overall strategy to glean as much public support for private profits as is possible while at the same time denying public support for job creation.

Lafer’s overall conclusion is exemplified in this passage:

Whatever the problem, it seems job training is the answer. The only trouble is, it doesn’t work, and the government knows it … Indeed, in studying more than 40 years of job training policy, I have not seen one program that, on average, enabled its participants to earn their way out of poverty.

Conclusion

You may be interested in reading this major report which we completed in 2008 on this topic – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy. Chapter 12, especially focuses on the skill shortage issue.

The neo-liberal era is characterised by the abandonment of full employment and the shift from understanding unemployment in terms of systemic failure (demand-deficiency) to blaming the individual.

This agenda change was consistent with the way in which economists sought to understand the world – from a micro perspective. The claims that the “business cycle was dead” exemplified the downgrading of macroeconomics as a viable discipline.

This allowed governments to oversee the increased precariousness of work and the persistent shortage of jobs. This was institutionalised in the late 1980s through the promotion of casual employment and by making the systematic harassment of unemployed people the object of labour market policy, beginning with the OECD-inspired ‘active employment strategy”.

To deflect our attention from the fact that our governments were willingly overseeing a systematic shortage of goods jobs new agendas emerged to reinforce the “individual” is to blame narrative.

Much of the skills shortage narrative fits into that broader neo-liberal agenda.

The maintenance of mass unemployment may be thought to facilitate the supply of affordable skilled labour, by undermining the bargaining position of skilled workers and enabling selective avoidance of the less skilled.

However, the absence of full employment, and the demise of public sector employment, have both contributed to an erosion of skills formation, atrophy of underutilised skill, and deterioration in the private sector’s willingness and ability to integrate less skilled people into their workplaces.

That is enough for today!

link broken – Creating effective local labour markets: a new framework for regional employment policy. Chapter 12,

Dear billie

I have fixed the link now. Thanks.

best wishes

bill

I am very skilled and throughout the GFC could not get a job. Then it is on to casual work which in many cases you are treated like a second class citizen. The pay is often less than the the full timers, you miss out on overtime and god help you if you make a mistake.

There are still many capable skilled workers looking for a full time job but because of health issues, Age or such they have no hope of gaining full time employment even though they have a proven track record.

Many crapping on about skills shortages dont want to pay the going rate but want to bring in cheap overseas labour.

Meanwhile a vast majority of the country believe the crap written in the paper and blame the poor old worker.

Glad some people see through the falicy.

on the same note I wrote to Julie Gillard before she became pm as she was spouting of on t.v. and radio what the government was doing for the recently retrenched. I told her it was an insult to retrenched workers for her to tell such rubbish. I give her credit for not repeating that statement after I sent the letter.

Now for a devil’s advocate style statement. MMT may be accurate (and I believe it is). Full employment should be our prime concern WITHIN the economy. But what about what’s happening outside our economy in the biosphere? What about the limits to growth? Given that we are overshooting the earth’s capacity, won’t the faster growth enabled by MMT prescriptions merely ensure this overshoot is more dramatic and more damaging? In a strange sort of way, isn’t the inefficiency and stupidity of neoclassical economics in retarding economic growth actually doing us a (slight) favour in slightly dealying the complete destruction of the carrying capacity of the biosphere?

Iconoclast, Given inadequate attention to environmental matters, then you are right: full employment and increased GDP arguably does more harm than good. But given proper attention to environmental matters, employment levels can perfectly well be raised. Given the latter “proper attention”, we’d just have more people employed making and installing home insulation, for example, rather than digging up fossil fuels and producing CO2.

Proper attention to the environment means slower growth in real GDP than would otherwise be the case, but it needn’t constrain employment growth.

@Ikonoclast,

I don’t believe they are doing us a favour in preventing a huge portion of society from being productive. They are merely just prolonging the slow agony.

Also, Bill has many times repeated that the MMT framework should be used to promote environment friendly growth (and also services to the elderly because of the ageing population). While MMT gives us the tools to achieve this, only governments (and therefore us by voting) can steer the economy towards this path, with the right combination of spending, taxation and regulation.

Roughly speaking, spend and stimulate demand on “green” technologies, tax heavily the not so green technologies, and outlaw (and enforce the law) deliberate non-green behaviour.

Also, it is true that our dear old planet Earth has limited quantity of natural resources, but nothing limits us to staying on Earth. Fund the space industry and the resource limit suddenly goes further away. But that’s the student in space technology speaking 🙂

I happened to watch a one-hour interview with Milton Friedman over the weekend that took place in 1994 on the occasion of the 50th anniversary release of Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, for which Friedman had written a new Forward. I have to admit I almost turned it off a couple of times in the first few minutes because of the disgust I felt over the pure childishness of some of his initial assertions, but I labored on, thinking that this was after all why I had chosen to watch it in the first place.

About two thirds of the way through it, however, things took a turn when he started talking about our welfare system. Oh, it should be scrapped because it is terribly inefficient, he said, BUT it should be replaced by a “negative income tax”, which he described as a guaranteed minimum income for everyone. Well hell, that’s right out of the 60s liberalism here, where we had a quite active movement to do exactly that, and there was actually government money funding pilot projects in it. What did Hayek think about this, Freidman was asked? Oh, Hayek thought there should at least be public provision for healthcare and for pensions.

So here’s the question. Friedman and Hayek are arguably the two highest deities of Neoliberalism, and here’s Freidman in his own words (video and audio so it can’t be denied!) saying they both supported a reasonable welfare state. How in hell do these bastards today who claim to be the intellectual offspring of these “great” thinkers get by denying what these men actually said?

Macroeconomics is fascinating; macroeconomists (most) are hypocrites.

Both Ralph and Bill have shown great insight.

There is much to do in the USA and elsewhere, if one is serious about converting their economies onto a sustainable path.

Considering the transport sector:

Double Tracking and Electrifying 66,000 miles of High Speed Main Line Rail to provide 175 mph passenger and 120 mph freight service

Conversion / Construction of 80,000 miles of electrified medium speed secondary rail (interurban) to provide 120 mph passenger and 80 mph freight service, such that no location, except parks and wilderness, is more than 10 miles from rail east of the plains and 20 miles west of the plains

Refurbishment of the nation’s waterway/canal system

The Electric Sector

Improvement of the Grid, using rail ROW for additional lines to support construction of 800 Gwe of wind, 200 Gwe of geothermal, and 150 Gwe of hydro.

The above could save 12 million barrels per day of petroleum consumption, and put millions to work.

Then there is reforestation, provision of elderly care, community policing, etc.

Fair Winds

INDY

It’s quite sick that goverments are creating unemployment and then turning around and blaming victims.

It’s like government would develop new kind of infectious disease in a laboratory, then release it to the population and blame the victims that get sick for having too weak immune systems.

@Ikonoclast,

Yourself and other wilting hearts like you really need to get your heads out of the sand, look around you and do something more productive to drive sustainability programs.

We already have all the technology, knowledge and resources to sustainably manage the planet with a significantly larger human population. It’s “possible” for every human to get perfectly adequate levels of nutrition, shelter, healthcare, transportation, recreation AND live in harmony with what’s left of the planet.

Recycling, integrated mass transportation, renewable energy programs, intensive agriculture and responsible management of indigenous nature are all perfectly feasible on a vastly larger scale than currently practiced. Why do some people think the solution is to sacrifice ourselves by living in sheds, riding a unicycle and eating mung beans all day?

The biggest problems are.

1) There is almost zero conversation on the optimal sustainable population…. start that conversation.

2) There are far too few programs to drive sustainable technologies and distribute resources fairly amongst the optimal sustainable population……join the conversation and participate in a program or two.

I know it “can” be done excepting the glaringly obvious fact all the leaders are complete assholes. I’m not expecting progress anytime soon. Maybe we have to wipe out the human race first and wait for a more sentient race to evolve. Plenty of time before the sun finally calls it a day!

@Ikonoclast,

I think that we would have a far lighter environmental footprint, even at full employment, if we sourced all our power from renewable energy and used electric cars. What’s stopping us from switching our energy sources? The propaganda that it will cost jobs. That’s 90% of the resistance right there.

I would then suggest that the more people are worried about jobs, the more likely they are to believe such rubbish, if only from the precautionary “just in case they are right” perspective.

I suspect that at full employment, it would be politically far easier to build a green economy. People are more generous when they aren’t afraid.

UK:

“Unproductive workers should lose their right to claim unfair dismissal, a leaked government report says.”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-15456585

I wonder whether getting rid of the unfair dismissal rules would be a bad thing in the round.

Now before you swing the rope over the lamp-post, let me explain.

Work is about humans operating together, and if those in charge decide somebody doesn’t fit, then they don’t fit. Dismissal always boils down to ‘how much’. So why not simple cut to the chase and say you can get rid of anybody you like by paying them salary equivalent to the median time it takes for somebody to find another job. (Say six months).

Once you have a Job Guarantee in place and the unions are no longer under the thumb is there a need for arcane rules about dismissal that simply lead to an elaborate and expensive dance ending in a payout anyway?

Making firing people more difficult makes hiring people more difficult, as simple as that.

Neil Wilson you are assuming that all employers act with integrity.

Here in Australia, in a regional area in 2004 the largest baker fired all the production line workers with 9.5 years of service just before the Christmas Summer holidays. This saved the company 4 weeks holiday pay plus long service entitlements that kick after 10 years working with one employer. The workers were replaced with permanent part timers who could work 25 hours a week max before they were eligible for sick pay, long service leave etc

This company continues to provide abyssmal returns to its shareholders whilst paying its executives obscene salaries.

Bill thanks for fixing the link

“This company continues to provide abyssmal returns to its shareholders whilst paying its executives obscene salaries.”

And if there is a Job Guarantee in the area then people will simply be able to say ‘no’ to such treatment. Word gets around and crap places close.

I don’t expect employers to act with integrity as a matter of construction. I expect the design of the system framework to force employers to start acting with integrity via competition for labour.

Why employment is an objective in itself? I would say that a real economy solving real problems should not target full employment but sharing productivity gains along the population, this means you can have more with the same or less income and working less time, not more.

This would actually improve quality of life leaving more free time for family, friends or personal projects which actually are more creative and socially productive that most paid work. However it does not matter what school of though in economics (at least the more important ones), they are so fixated with their theories and non-sense that can’t see the forest beyond the trees and solve real problems.